Chinatowns in the United States

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (August 2021) |

| Chinatown | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 唐人街 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國城 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国城 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 華埠 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 华埠 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Chinatowns |

|---|

This article contains a list of the Chinatowns which are either officially designated neighborhoods or historically important ones in the United States. Many of these Chinatowns were developed in the 1800s by the Chinese diaspora and have served as ethnic Chinese enclaves since then.

History

Chinatowns in the United States were first primarily located in the largest cities, notably New York City, San Francisco, Boston, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Chicago, with the earliest Chinatowns on the west coast and newer ones appearing further east as Chinese immigrants sought opportunities in other parts of the country. Continuous demographic changes have drastically altered come Chinatowns, especially smaller ones. Today, many urban Chinatowns are no the longer ethnic enclaves they once were, but try to retain distinctive architecture or identities to appeal to tourists. In New York City, however, satellite Chinatowns in the boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn on Long Island defy this trend, fueled by continuing large-scale immigration from mainland China.[1][2][3]

A significant timeline of the history of Chinatowns in the U.S follows:

- 1840s–1860s – Many initial Chinatowns developed in the west, spurred by the California Gold Rush and the Transcontinental railroad, including the San Francisco's Chinatown.

- 1863 – The Emancipation Proclamation opened up new opportunities for Chinese in the Southern United States.

- 1860s, 1870s, 1880s – Racial tensions and labor tensions led to incidents such as the Rock Springs Massacre.

- 1882–1943 – Chinese Exclusion Act in effect, banning Chinese immigration into the United States.

- 1943 – Repeal of Chinese Exclusion Act, Chinatown populations start to rise again.

- 1970s – End of Vietnam War.

- 2010s – The downturn of U.S. economy and rise of China's economy caused reverse migration and they decay of Chinatowns.[4]

Demographics

Most Chinatowns started as enclaves of ethnic Chinese people and many of these Chinatowns have experienced gentrification and demographic shifts. While some Chinatowns have retained their status as an ethnic Chinese enclave, many of them have lost that status. The cities with the ten highest Chinese American populations according to the 2015 American Community Survey, were as follows:

- New York City (549,181)

- San Francisco (179,644)

- Los Angeles (77,284)

- San Gabriel Valley core cities and CDPs (additional 225,543)

- San Jose (72,141)

- Honolulu (53,119)

- Chicago (51,809)

- San Diego (40,033)

- Philadelphia (35,732)

- Oakland (33,818)

- Houston (32,968)

Arizona

Phoenix

The Phoenix, Arizona Chinatown was started in the 1870s[5] and lasted until the 1940s, with the general population scattering throughout the city thereafter.[6] Sources from a research project indicated that more than one Chinatown existed in the city of Phoenix, with one around First Street and Madison[7][8] and a second at First and Adams Street in the present location of the Talking Stick Resort Arena.

California

Given its relative proximity to East Asia and Southeast Asia, California has the largest number of Chinese among the American states,[9] including the well-known Chinatown in San Francisco, an all-Chinese town of Locke built by Chinese immigrants, and Chinatowns in various cities throughout the state.

Eureka

There was a Chinatown in Eureka, which was established around the 1880s. The district spanned one block at Fourth and E streets.[10]

Fresno

Fresno still has a neighborhood officially called Chinatown, near downtown. However, most of its Chinese businesses and architecture are gone. Though the neighborhood had a vibrant Chinese community in the early 1900s.[11]

Greater Los Angeles Area

Los Angeles

In the city of Los Angeles proper, the old inner-city Chinatown was built during the late 1930s–the second Chinatown to be constructed in Los Angeles. Formerly a "Little Italy," it is presently located along Hill Street, Broadway and Spring Street near Dodger Stadium in downtown Los Angeles with restaurants, grocers, and tourist-oriented shops and plazas. A sculpture of dueling gold dragons spans Broadway and marks the entrance to Chinatown with a statue honoring the Kuomintang founder Dr. Sun Yat-sen adorning the northeast section. The enclave contains Buddhist temples, a Chinese Christian church (with services conducted in Cantonese), and Thien Hau Temple dedicated to the Chinese Goddess of the Sea which is cater to Chinese and Vietnamese worshipers. Chinatown is home to family and regional associations and general service organizations for long time immigrants (called in Cantonese: 老華僑; Jyutping: lou5 waa4 kiu4) as well as ones founded by and for a second wave of Indochina-born immigrants after the Vietnam War ended.

San Gabriel Valley

The San Gabriel Valley in the eastern suburbs of Los Angeles is home to the U.S.'s first suburban Chinatown (in Monterey Park, California), according to the Los Angeles Times, and is now one of the Chinese enclaves in the San Gabriel Valley.[12][13] According to the same source, starting in 1977, Frederic Hsieh bought up multiple properties in an effort to create what he described would be a "mecca for Chinese". Timothy Fong wrote a book that documents the history in the transforming of Monterey Park from an ordinary suburb to a Chinatown.[14] Samuel Ho documented that Monterey Park falls into the "new Chinatown" category, with Houston cited as an example from which it follows.[15] There are now approximately 15 local cities and communities with Chinese plurality: Alhambra, Arcadia, Diamond Bar, East San Gabriel, Hacienda Heights, Mayflower Village, Monterey Park, North El Monte, Rosemead, Rowland Heights, San Gabriel, San Marino, South San Gabriel, Temple City, Walnut.

Irvine

Irvine is a growing suburban Chinatown in Orange County, as more Chinese people are expand into the San Gabriel Valley. Many Chinese business establishments are situated in the El Camino Real and Walnut neighborhoods.[16][17]

Cerritos

Cerritos is a majority Asian city located on the border of Orange County and Los Angeles County. There are significant Chinese - owned and operated businesses along South St that continue into the neighboring city of Artesia

Little Saigon

A group of cities located in central north Orange County have a majority Vietnamese population. Many of the Vietnamese are of mixed Chinese origin, especially Cantonese, as Chinese-Vietnamese families were some of the main targets when Communist North Vietnam conquered South Vietnam. Many of the older residents can still speak Cantonese and Chinese-style restaurants are also common in the area, including Cantonese BBQ butchers. This area is centered on Westminster, Garden Grove, Midway City, and Fountain Valley, while also including a presence in the neighboring cities of Santa Ana, Anaheim, Stanton, and Huntington Beach.

Chino Hills

Chino Hills is a suburban city located on the border of Los Angeles County and San Bernardino County. It is growing as a continuation of the Chinese community in San Gabriel Valley and is known for its high-performing schools and clean environment.

Ventura

Ventura had a flourishing Chinese settlement in the early 1880s. The largest concentration of activity, known as China Alley, was across Main Street from the Mission San Buenaventura. China Alley was parallel with Main Street and extended east off Figueroa Street between Main and Santa Clara Streets.[18] The city council has designated the China Alley Historic Area a point of interest in the downtown business district.[19]

Locke

The Sacramento River delta town of Locke was built in 1915 as a distinct rural Chinese enclave. A thriving agricultural community in the early 20th century, it is now largely uninhabited by Chinese-Americans. A historic district of 50 wood-frame buildings along Main Street, Key Street and River Road was designated a historic district in 1990.[20]

Sacramento

Throughout the early 1840s and 1850s, China was at war with Great Britain and France in the First and Second Opium Wars. The wars, along with endemic poverty in China, helped drive many Chinese immigrants to America. Many first came to San Francisco, which was then the largest city in California, which was known as "Dai Fow" (The Big City) and some came eventually to Sacramento (then the second-largest city in California), which is known as "Yee Fow" (Second City). Many of these immigrants came in hopes for a better life as well as the possibility of finding gold in the foothills east of Sacramento.

Sacramento's Chinatown was located on "I" Street from Second to Sixth Streets. At the time, this area of "I" Street was considered a health hazard becaue it was located in a levee zone and was lower than other parts of the city. Throughout Sacramento's Chinatown history there were fires, acts of discrimination, and prejudicial legislation such as the Chinese Exclusion Act.[21] Ordinances on what was viable building material were set into place to try to prevent Chinese settlement. Newspapers wrote stories that portrayed the Chinese in an unfavorable light to inspire ethnic discrimination and drive the Chinese away. As the years passed, a railroad was created over parts of the Chinatown. Further politics and laws would make it even harder for Chinese workers to make a living in Sacramento. While the east side of the country fought for higher wages and fewer working hours, many cities in the western United States wanted the Chinese out, believing that they were stealing jobs from the white working class.[when?]

Salinas

In the 1880s, farm labor in Salinas was done by many Chinese immigrants. Salinas boasted the second largest Chinatown in the state, slightly smaller than San Francisco.[22]

San Diego

San Diego's Chinatown was founded in the 1870s around Market Street and Third Avenue, but faded quickly after World War Two. In 1987, due to its historic and cultural value, the city council of San Diego sought to preserve the area and officially designated it the Asian Pacific Thematic Historic District, which partially overlaps the burgeoning and gentrified Gaslamp Quarter Historic District (the center of the San Diego's trendy nightlife scene). The annual San Diego Chinese New Year Food and Cultural Faire is presented in this particular district, and the San Diego Chinese Heritage Museum is located here.

San Francisco Bay Area

San Francisco

The first and one of the largest, most prominent and highly visited Chinatowns in the Americas is San Francisco's Chinatown. Founded in 1848, Chinatown was destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and was later rebuilt and re-realized, using a Chinese-style architecture that has been criticized as garish and touristy. For many years, a center of tong wars and later gang activism, Chinatown is now much safer than it was in years past. Chinatown receives millions of tourists annually, making the community, along with Alcatraz and Golden Gate Bridge, one of the prime attractions and highlights of the city of San Francisco, as well as the centerpiece of Chinese-American history.

Besides the main thoroughfare of Grant Avenue and various side streets, Chinatown has several side alleys, including Ross Alley. Contained within this alley is a mix of touristy stores, tiny barber shop, as well as a fortune cookie factory. Ross Alley used to have brothels, but they no longer exist. Also within the confines of Chinatown is the Woh Hei Yuen Recreation Center and Park on Powell Street. The Tin How Temple (Queen of Heaven and Goddess of the Seven Seas) on Waverly Place which was founded in 1852 is the oldest Chinese temple in the United States.

The San Francisco Chinatown hosts the largest Chinese New Year parade in the Americas, with corporate sponsors such as the Bank of America and the award-winning and widely praised dragon dance team from the San Francisco Police Department, composed solely of Chinese-American SFPD officers (the only such team in existence in the United States). In its founding, it received the grant from the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, otherwise known as the Chinese Six Companies. As Chinatown and many Chinese-Americans in the San Francisco Bay Area have historical or current roots in province of Guangdong, China (particularly Taishan County) and in Hong Kong, these dances are mostly performed in the southern Chinese style. San Francisco's Chinatown is also the birthplace of chop suey and many other dishes of American Chinese cuisine.

With its Chinatown as the landmark, the city of San Francisco itself has one of the largest and predominant concentrations of Chinese-American population centers, representing 20% of total population as of the 2000 Census, Though Chinatown remains the cultural and symbolic anchor of the Bay Area Chinese community, increasing numbers of Chinese-Americans do not live there, instead residing in Chinese enclaves in the Richmond and Sunset districts, or elsewhere in the Bay Area.

Oakland

Oakland's Chinatown is frequently referred to as "Oakland Chinatown" in order to distinguish it from nearby San Francisco's Chinatown. Originally formed in the 1860s, the Chinatown of Oakland – centering upon 8th Street and Webster Street – shares a long history as its counterpart in the city of San Francisco as Oakland's community remains one of the focal points of Chinese American heritage in the San Francisco Bay Area. Oakland's Chinatown is not as touristy as San Francisco's Chinatown as its local economy tends not to rely on tourism as much. The local government of Oakland has since promoted it as such as it is considered one of the top sources of sales tax revenue for the city. The Chinatown does not have an ornamental entrance arch (paifang) but the streets of the community are adorned with road signs in English with Chinese rendering.

Today, while it remains a Cantonese-speaking enclave, it is not exclusively Chinese anymore, but more of a pan-Asian neighborhood which reflects Oakland's diversity of Asian communities, including Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, Filipinos, Japanese, Cambodian, Laotian, Mien, Thai, and others. In addition to the standard Chinese New Year festivities, the Oakland Chinatown Streetfest (held by the Oakland Chinatown Chamber of Commerce) is held yearly in August and features Chinese lion dances, parades, music, cooking demonstrations and contests, a food festival, and various activities.

Napa

Napa had a Chinatown that was established in the mid-1800s, located on First Street. It had 300 residents. Many of its residents provided manual labor in the area.[23]

San Jose

San Jose was home to five Chinatowns that existed until the 1930s.[24] The initial Chinatowns in San Jose were frequently burned down by arson, with artifacts from May 1887 recently discovered around the San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art, which is located at 560 South 1st Street.[25] Another Chinatown was excavated during an urban renewal project to build the Fairmont Hotel and Silicon Valley Financial Center on Market and San Fernando Streets.[26] According to another article, this Chinatown was also known as the "Plaza Street Chinatown", which grew rapidly from the 1860s to the 1870s and was home to "... several hundred Chinese." According to this article, the area at the time was subject to controversy as many whites often complained to the city council about the area as "bothersome". By 1870, the area was burned to the ground with many Chinese evicted from the area as the anti-Chinese public sentiment grew.[27]

Later in history, John Heinlen, a farmer and businessman, planned a six block Chinatown with brick structures with water and pipes in the area of Sixth Street and Cleveland Street in 1887, to the dismay of the non-Chinese public and caused public outrage. The area was then known as "Heinlenville" and contained a variety of merchants, barbers, traditional doctors, and Chinese herbal medicine, and the Ng Shing Gung temple. The area was surrounded by Little Italy and co-existed harmoniously, but then dwindled in the 1920s as the younger generations sought careers outside the area and with a lack of new Chinese coming in due to the Chinese Exclusion Act, the area lost almost all of its Chinese population.[28] Some artifacts from this Chinatown are now located in Kelley Park. At the time, an existing Japantown nearby was evacuated due to the war, but was repopulated after the internment of the Japanese-Americans.

San Luis Obispo

Someone who overcame much of that was On Wong, also known as Ah Louis. In the 1870s, Wong was one of the first Chinese immigrants in San Luis Obispo. He founded the Ah Louis store and was also a labor contractor, securing 160 Chinese laborers for the construction of the Cuesta Grade Road, railroads, and mining or draining of the Laguna Lake Area. “The Chinese built San Luis Obispo. They made the railroad, which is extremely important for this town even being on the map,” said Russell Kwong, owner of Mee Heng Low restaurant.

But at the time, there was statewide Chinese racism.

“In 1882, you have the Chinese Exclusion Act passed at the federal level, which basically kept out all Chinese laborers,” said Coastal Awakening Executive Director James Papp. “It also tended to keep out Chinese women on the theory that you didn't want the Chinese to start their own communities.”

“They were never recognized. The reason is because of their hair color, because of their skin color. So that is not fair,” said Cal Poly Landscape Architecture Professor Emerita Alice Loh.

Santa Rosa

There was a Chinatown in Santa Rosa, present in the early 1900s, and was removed afterward. It was located on Second and Third Streets, near Santa Rosa Avenue, in downtown Santa Rosa. The district had around 200 residents.[29][30]

Stockton

Stockton, California is home to a small Chinatown on Chung Wah Lane, East Market Street and East Washington Street. In 1906, Stockton's Chinatown "... had the largest Chinatown in California with over 5,000 inhabitants..." due in large part to the 1906 San Francisco earthquake that caused a "... swelling [of] the Chinese population in Stockton."[31]

On Lock Sam, the city's oldest restaurant was founded in 1898. The community was once quite large but, after development in the 1950s and 1960s and the construction of the Crosstown freeway, businesses moved, buildings were demolished, new buildings were built, and the community changed forever. There is still a Chinese New Year Parade merged with the Vietnamese New Year celebrations.[32][33]

Colorado

Denver

Chinatown in Denver, Colorado, was a neighborhood on Wazee Street in what is now the "LoDo section of the city...."[34] The first recorded Chinese person was of a man from southern China named "John" dated June 29, 1869, as documented by the Colorado Tribune.[35]

It was also referred to as "Hop Alley" and it was torn apart by riots in the 1880s.[36] A St. Louis newspaper dated November 1, 1880 documented the complete destruction of the neighborhood as "Chinatown Gutted by Murderous Scoundrels".[37]

Connecticut

Norwich and Montville

The development of the Mohegan Sun casino has caused major demographic changes to the surrounding communities of Montville and Norwich. After the attacks of 9/11 led to a loss of garment and service jobs in Manhattan Chinatown, many relocated to work in the then-new Connecticut casino, which produced an unofficial suburban "Chinatown" in the vicinity. However, as the influx of Chinese workers grew, racial tensions also rose in the area. To some pre-existing residents, the changes brought by the new residents were unwanted or considered unsightly. Some disapproved of how groups of Chinese residents chose to live together in single-family suburban homes, a practice typically used to save money to send back to family or to eventually purchase their own homes. Complaints about the introduction of Chinese agriculture to the front lawns of neat neighborhoods were also made, as many of the new residents made use of their lawns by gardening openly. But despite any resistance to the migration of the Chinese community, a large ethnic population was quickly introduced to southeastern Connecticut.[38][39]

District of Columbia

Chinatown in Washington, D.C. is a small, historical neighborhood east of downtown consisting of about 20 ethnic Chinese and other Asian restaurants and small businesses along H and I Streets between 5th and 8th Streets, Northwest. It is known for its annual Chinese New Year festival and parade and the Friendship Arch, a Chinese gate built over H Street at 7th Street. Other nearby prominent landmarks include the Capital One Arena, a sports and entertainment arena, and the Old Patent Office Building, which houses two of the Smithsonian museums (the National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian American Art Museum). The neighborhood is served by the Gallery Place-Chinatown station of the Washington Metro.[40]

Hawaii

Honolulu

The official historical and current Chinatown of Honolulu, Hawaii is located near North Hotel Street and Maunakea Street and contains traditional Chinese businesses. Unlike Chinatowns in the continental United States which were largely established by immigrants from Taishan, Honolulu's Chinatown was started in the 1890s by early settlers from Zhongshan, Guangdong Province. They migrated to Hawaii for work on the islands' sugarcane plantations and rice fields, and many gradually became successful merchants and relocated to the city of Honolulu. As with many other Chinatowns in the United States, it was noted for its unsanitary conditions throughout the 19th century, including an outbreak of bubonic plague in 1899.[41] For a period after the 1940s, it degenerated into a red-light district.[42]

Today, it is a diverse neighborhood with many East Asian and Pacific Islander businesses. Recent investment and planning has dramatically transformed the once decaying and unsafe neighborhood to an upscale Asian-inspired arts and business district, blending the traditional Chinese bazaars and family owned stores. Ethnic Chinese from Vietnam make up much of the population. Businesses include markets, bakeries, a Chinese porcelain shop, and shops specializing in ginseng herbal remedies. There are often bazaars and street peddlers in the Kekaulike Market located on Kekaulike Street. A variety of restaurants serving Hong Kong-style dim sum and Vietnamese beef noodle soup are common.

Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen received his Western education in Hawaii, and his history is tied to Honolulu's Chinatown. The area once served as his base of operations for a series of crusades against the ruling Qing Dynasty in China that culminated in the Revolution of 1911. There is a monument to Sun in Honolulu's Chinatown, and the Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Park is named in his honor.[43]

Illinois

Chicago

The Chinatown in Chicago is a traditional urban ethnic enclave, occupying a large portion of the Armour Square region on the city's near south side. The intersection of Wentworth Avenue at Cermak Road is the neighborhood's historic epicenter. Chinatown has historically been dominated by Chinese-American commercial interests, though in recent years, large-scale construction of residential developments, particularly east of Canal Streets and the area adjacent to Ping Tom Park south of W.18th Street, have exponentially increased the number of residents in the area. While it is a cultural tourist attraction for visitors, Chinatown also attracts Chinese emigrants hailing from China as a gateway neighborhood. The annual Chinese New Year and Chinese Double Ten Day Parade are both held in Chinatown.

Louisiana

New Orleans

New Orleans was once home to one of the largest Chinatowns in the Southern United States. The first significant migration of Chinese to Louisiana took place during Reconstruction after the American Civil War, between 1867 and 1871, when local planters imported hundreds of Cantonese contract laborers from Cuba, California, and directly from China as a low-cost replacement for slave labor.[44] By the mid-1870s, nearly all of these laborers had abandoned the plantations and migrated to the cities of the South, especially New Orleans, in search of higher pay and better working conditions. They were followed by Chinese merchants from California and other states, who supplied the laborers, imported tea and other luxury goods to the Port of Orleans, and exported cotton and dried shrimp to China.[45]

By the 1880s, these merchants had developed a small Chinatown on the 1100 block of Tulane Avenue, between Elk Place and South Rampart Street, near the modern Tulane stop on the North Rampart Streetcar line. Though much smaller than the Chinatowns of the West Coast or the industrial cities of the north, New Orleans Chinatown was the site of several dry goods groceries, import/export companies, apothecaries, restaurants, laundries, and the meeting halls of several Chinese associations.[46] Chinatown continued to exist for six decades, until its destruction by WPA re-development in 1937, during the Great Depression. Several office towers stand on the site of the former Tulane Avenue Chinatown. A few Chinese businesses attempted to build a second Chinatown on the 500-block of Bourbon Street, but this smaller Chinatown also died out over the next thirty years. Today, only the former meeting hall of the On Leong Merchants Association still remains on 530 Bourbon Street.[47]

Maine

Portland

Chinatown in the U.S. city of Portland, Maine once existed around Monument Square and traversed mostly on Congress Street. The first Chinese person arrived in 1858 with the Chinatown forming around 1916 until around 1953. The last vestiges of Chinatown lingered until 1997 when the last Chinese laundry closed and all buildings demolished by then through urban renewal.[48] Portland's Chinatown existed modestly with most Chinese being isolated due to discrimination and the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. By 1895, there were enough Chinese people that a Chinese community began to form, though mostly with men whose wives were prohibited from migration by the newly created law. The community celebrated their first Chinese New Year that year (1895). By 1920, around 30 Chinese laundries existed in the city. In 1903, a union formed to fix prices for laundromats and consisted of around 100 people who owned the laundries. By around the 1950s, the Chinese community had shrunk to the point that Chinatown almost ceased to exist. By 1997, the last laundry was demolished wiping out the last remaining vestige of Chinatown.[49] Most Chinese men who lived in Chinatown attended a Chinese American church with some going to China as missionaries.[48]

Maryland

Baltimore

Baltimore, Maryland was home to a small Chinatown. Historically, Baltimore had at least two districts that were called "Chinatown" where the first one existed on the 200 block of Marion Street[50] ring the 1880s. A second and current location is at the 300 block of Park Ave., which was dominated by laundries and restaurants. The initial Chinese population came because of the transcontinental railroad, however, the Chinese population never exceeded 400 as of 1941. During segregation, Chinese children were classified as "white" and went to the white schools. Chinatown was largely gone by the First World War due to urban renewal. Though Chinatown was largely spared from the riots of the 1960s, most of the Chinese residents moved to the suburbs.[51] As of 2009, the area still shows signs of blight and does not have a Chinese arch.[52]

Rockville, Potomac, and North Potomac

Rockville, in addition to North Potomac with a 27.59% Asian population and Potomac with close to 15%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, Rockville is home to one of the largest Chinese communities in Maryland[53] According to the U.S. Census conducted in 2000, 14.5% of North Potomac's residents identified themselves as being of Chinese ancestry, making North Potomac the area with the highest percentage of Chinese ancestry in any place besides California and Hawaii.[citation needed] According to the Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS) enrollment demographic statistics, the two high schools in Montgomery County with the highest reported Asian ancestry are Thomas S. Wootton High School in Rockville, MD with a 32.1% Asian population and caters to the communities in North Potomac, Rockville, and Potomac, MD, and Winston Churchill High School in Potomac, MD with a 23.0% Asian population.[54][55][citation needed] Although North Potomac and Potomac have the highest concentration of Asian population in Maryland, the areas are largely residential and consist of suburban subdivisions. Thus, the more commercially favorable Rockville has become the center for Chinese/Taiwanese businesses since it is the county seat of Montgomery County and has large economic activity along Rockville Pike/Wisconsin Avenue (MD Route 355) in addition to having its own middle class and upscale residential areas. Rockville is widely considered to be a "Little Taipei" due to the area's high concentration of Taiwanese immigrants.[citation needed]

Although it is considered a satellite of the Washington, D.C., Chinatown, Phuong Ly wrote in the Washington Post that the Montgomery County Chinatown is the "real Chinatown".[56] According to the article, Rockville's Chinatown spans along Rockville Pike from Halpine Road to East Jefferson Street, along E Jefferson Street and then along North Washington Street. Close to 30,000 people of Chinese descent live in Montgomery County, most of whom were drawn to the "good schools" and is home to at least three Chinese newspapers.[57] Cynthia Hacinli states that "fans of authentic Chinese food" come here instead of the downtown Chinatown on H Street.[58]

After the riots of 1968, many Chinese sought refuge in the suburbs of Maryland and Virginia, thus starting the decline of the H Street Chinatown. [59] According to another article, the largest concentrations of Chinese in the Washington, DC, area are in Montgomery County, Maryland at around 3%, while concentrations in Fairfax and Arlington counties in Virginia are around 2 to 3%, which dwarfs that of Washington's Chinatown at around 3%.[60] As the shift continues, the role that the urban Chinatown once played is now replaced by the "satellites" in the suburbs. It turns out that the "best food is no longer in Chinatown" and "... the closest Chinese grocery retailer is in Falls Church, Virginia."[61]

The Chinese New Year parade is held in the Rockville Town Square.[62]

Massachusetts

Boston

The sole established Chinatown of New England is in Boston, on Beach Street and Washington Street near South Station between Downtown Crossing and Tufts Medical Center. There are many Chinese, Japanese, Cambodian, and Vietnamese restaurants and markets in one of the largest Chinatowns in the United States.

In the pre-Chinatown era, the area was settled in succession by Irish, Jewish, Italian, and Syrian immigrants as each group replaced another. Syrians were later succeeded by Chinese immigrants, and Chinatown was established in 1890. From the 1960s to the 1980s, Boston's Chinatown was located in the Combat Zone, which served as Boston's red light district, but sandwiched between the dual expansions of Chinatown from the East and Emerson College from the West, the Combat Zone, while still in existence, has shrunk to almost nothing.

Currently, Boston's Chinatown is experiencing gentrification. High-rise luxury residential towers are built in and surrounding the area that was overwhelmingly three, four, and five-story small apartment buildings intermixed with retail and light-industrial spaces.[63][64]

Michigan

Detroit

Detroit's Chinatown was originally located at Third Avenue, Porter St and Bagley St, now the permanent site of the MGM Grand Casino.[65] In the 1960s, urban renewal efforts, as well as the opportunity for the Chinese business community to purchase property led to a relocation centered at Cass Avenue and Peterboro.[66] However, Detroit's urban decline and escalating street violence, primarily the killing of restaurateur Tommie Lee, led to the new location's demise, with the last remaining Chinese food restaurant in Chinatown finally shut its doors in the early 2000s. Although there is still a road marker indicating "Chinatown" and a mural commemorating the struggle for justice in the Vincent Chin case, only one Chinese American establishment still operates within the borders of the City of Detroit. The Association of Chinese Americans Detroit Outreach Center,[67] a small community center, serves a handful of new Chinese immigrants who still reside in the Cass Corridor.

Missouri

St. Louis

Chinatown in St. Louis, Missouri, was a Chinatown near Downtown St. Louis that existed from 1869 until its demolition for Busch Memorial Stadium in 1966.[68] Also called Hop Alley, it was bounded by Seventh, Tenth, Walnut and Chestnut streets.[69] The first Chinese immigrant to St. Louis was Alla Lee, born in Ningbo near Shanghai, who arrived in the city in 1857. Lee remained the only Chinese immigrant until 1869, when a group of about 250 immigrants (mostly men) arrived seeking factory work.[70] In January 1870, another group of Chinese immigrants arrived, including some women.[71] By 1900, the immigrant population of St. Louis Chinatown had settled at between 300 and 400.[72] Chinatown established itself as the home to Chinese hand laundries, which in turn represented more than half of the city's laundry facilities.[73] Other businesses included groceries, restaurants, tea shops, barber shops, and opium dens.[74] Between 1958 and the mid-1960s, Chinatown was condemned and demolished for urban renewal and to make space for Busch Memorial Stadium.[69]

Montana

The history of Chinese in Montana closely ties with the building of the Northern Pacific Railroad in the 1860s in many cities and towns including Butte, Big Timber, and other places. An archaeological find uncovered remnants of laundromats and other architectures relating to the Chinese culture.[75] According to another article, of the 20,000 residents of Montana in the 1870s, as many as 1,949 were Chinese. Today, one of the few reminders of Chinese society in Montana is the Chinese New Year parade that is held at the Mai Wah Museum in Butte.[76]

Big Timber

At the end of the 19th century, many Chinese people called Big Timber, Montana home. According to the Billings Gazette, Chinese artifacts dating from the late 1800s to the 1930s were found. The artifacts showed that "... Chinese restaurants, laundries and even a house of prostitution did business in the southcentral Montana town."[77] Justin Moschelle, a Master's student at the University of Montana took up an archaeological investigation in the summer of 2008 and uncovered bits and fragments of the once existent Chinatown. Built in the 1880s, "... the city block bounded by Anderson, First, Mcleod, and Front streets became the unofficial Chinatown of Big Timber."[78] The article further clarifies that the Chinese history within this Montana town was nearly wiped out with vandals destroying graves and any remaining relics of this community. It wasn't until 2008 that the discovery was made where the town of Big Timber and the U.S. state of Montana nearly lost all traces of any presence of Chinese society.[79][80] According to the findings, the last Chinese left during the 1930s, "... presumably to larger Chinese settlements in California or even back to China. All that remains of the Chinese presence in Big Timber, is a handful of artifacts and stories of Chinese tunnels and the opium trade."[78]

Butte

The Chinatown and the history of the Chinese migrants in Butte is documented in the Mai Wah Museum. Due to the mining boom in Butte, many Chinese workers moved in and set up businesses that led to the creation of a Chinatown. There was anti-Chinese sentiment in the 1870s and onwards due to racism on the part of the white settlers, exacerbated by economic depression, and in 1895, the chamber of commerce and labor unions started a boycott of Chinese owned businesses. The business owners fought back by suing the unions and winning. The decline of Butte's Chinatown that started in 1895 and continued until only 92 Chinese people remained by 1940 in the entire city. After that, the influence the Chinese had on the area was largely gone as they moved out one by one.[81]

Cedar Creek

Cedar Creek, Montana (location referenced in the Battle of Cedar Creek, Montana Territory) was also home to a Chinatown. During an excavation project in 1995 to prove the presence of Chinese in the area, the initial findings did not show much. However, a 2007 finding uncovered "...fascinating information about the Cedar Creek Chinese population" and the University of Montana and the United States Forest Service have planned to do additional work to trace back to a potentially lost part of Montana's Chinese history.[82]

Helena

Helena, Montana was at one time home to a Chinatown at Reeder's Alley according to the Helena's Ghost Walk tourist attraction.[83] According to another source, Reeder's Alley, as the area was referred to, bordered a "... thriving Chinatown" which completely vanished by the 1970s. Due to some efforts to preserve the historical aspects of the buildings, the area was spared from complete demolishment, and is fixed up as part of the museum.[84] According to the 1880 US Census, Helena's Chinatown had a Chinese population of 1,765, of which 359 of them were living in the metropolitan area. At that time, this Chinatown was the largest in the state of Montana.[85]

Nebraska

Omaha

The Chinese community in Omaha was originally established in the 1860s by the Union Pacific Railroad and other western industrial concerns as the railroad swept west starting in Omaha. In 1870, Harper's Weekly claimed 250 Chinese laborers passed through Omaha to build a railroad in Texas.[86] The city's first noted burial of a Chinese person occurred at Prospect Hill Cemetery in July 1874, and an Omaha newspaper noted the local Chinese population was 12 men and one woman. In 1890, there were Omaha has 91 Chinese residents. The Omaha City Directory in 1895 listed at least 21 Chinese-owned laundries. After the Omaha World-Herald reported that 438 men, women, and children were brought to Omaha from China to help with the Chinese village at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha, the US Census found 93 Chinese people lived in Omaha in 1900.[87] In 1916, the newspaper reported 150 Chinese residents in Omaha when the local On Leong Tong opened.[88]

Nevada

Carson City, Reno, and Virginia City

The city of Carson City, Nevada was once home to a Chinese community of 789 residents. The Chinatown was located near the State Capitol buildings on Third Street between 1855 until 1908 when Chinatown burned to the ground. In 1880, one in five people living in Carson City was Chinese, but by 1950, that number was close to zero.[89] Another source claims that Carson City had the most number of Chinese in 1880 with close to 5,000, other cities in Nevada such as Virginia City, and Reno also had well established Chinatowns.[90] Reno's Chinatown was burned down in 1878 by the Reno Workingmans Party.[91] Las Vegas is currently home to the largest Asian population in the state of Nevada. The current home Chinatown begins on Spring Mountain Road and Procyon Street. It extends for 2 miles to Jones Street. There is also a growing presence of Asian restaurants and markets along South Rainbow Blvd.

New Jersey

Newark

Newark's Chinatown was an unincorporated community and neighborhood within the city of Newark in Essex County, New Jersey, United States. It was an ethnic enclave with a large percentage of Chinese immigrants, centered along Market Street from 1875 and remaining on some scale for nearly one hundred years. The center of the neighborhood was directly east of the Government Center neighborhood. The first Chinese businesses appeared in Newark in the second half of the 19th century and in the early part of the 20th century. By the 1920s, the small area had a Chinese population of over 3000.[92]

In 1910, a small lane with housing and shopping was built called Mulberry Arcade, connecting Mulberry Street and Columbia Street between Lafayette and Green Streets. In the 1920s, recurring federal opium raids[93] disrupted the community, causing many to move to more peaceful places. Despite an attempt to revive the neighborhood decades later, the Mulberry Arcade (the center of Chinatown) was removed in the 1950s.

New York

New York City

The New York metropolitan area contains the largest ethnic Chinese population outside of Asia, comprising an estimated 893,697 uniracial individuals as of 2017,[94] including at least 12 Chinatowns – six[95] (or nine, including the emerging Chinatowns in Corona and Whitestone, Queens,[96] and East Harlem, Manhattan) in New York City proper, and one each in Nassau County, Long Island; Edison, New Jersey;[96] and Parsippany-Troy Hills, New Jersey, not to mention fledgling ethnic Chinese enclaves emerging throughout the New York City metropolitan area. Chinese Americans, as a whole, have had a (relatively) long tenure in New York City.

The first Chinese immigrants came to Lower Manhattan around 1870, looking for the "golden" opportunities America had to offer.[97] By 1880, the enclave around Five Points was estimated to have from 200 to as many as 1,100 members.[97] However, the Chinese Exclusion Act, which went into effect in 1882, caused an abrupt decline in the number of Chinese who immigrated to New York and the rest of the United States.[97] Later, in 1943, the Chinese were given a small quota, and the community's population gradually increased until 1968, when the quota was lifted and the Chinese American population skyrocketed.[97] In the past few years, the Cantonese dialect that has dominated Chinatown for decades is being rapidly swept aside by Mandarin Chinese, the national language of China and the lingua franca of most of the latest Chinese immigrants.[98]

Manhattan

The Manhattan Chinatown (simplified Chinese: 纽约华埠 ; traditional Chinese: 紐約華埠; pinyin: Niŭyuē Huá Bù), home to the largest enclave of Chinese people in the Western Hemisphere,[99][100][101][102][103] is located in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. Within Manhattan's expanding Chinatown lies a Little Fuzhou on East Broadway and surrounding streets, occupied predominantly by immigrants from the Fujian Province of Mainland China. Areas surrounding the "Little Fuzhou" consist mostly of Cantonese immigrants from Guangdong Province, the earlier Chinese settlers, and in some areas moderately of Cantonese immigrants.

In the past few years, however, the Cantonese dialect that has dominated Chinatown for decades is being rapidly swept aside by Mandarin, the national language of China and the lingua franca of most of the latest Chinese immigrants.[104] The energy and population of Manhattan's Chinatown are fueled by relentless, massive immigration from Mainland China, both legal and illegal in origin, propagated in large part by New York's high density, extensive mass transit system, and huge economic marketplace.

The early settlers of Manhattan's Chinatown were mostly from Taishan and Hong Kong of the Guangdong Province of China, which are the Cantonese speakers and also from Shanghai.[105] They formed most of the Chinese population of the area surrounded by Mott and Canal Streets.[105] The later settlers, from Fuzhou, Fujian, form the Chinese population of the area bounded by East Broadway.[105] Chinatown's modern borders are roughly Grand Street on the north, Broadway on the west, Chrystie Street on the east, and East Broadway to the south.[105]

After 9/11, approximately 23% of these residents have relocated to the surrounding communities of the Mohegan Sun casinos, mainly in Norwich, Connecticut, and creating a new Chinatown there.

Queens

The Flushing Chinatown, in the Flushing area of the borough of Queens in New York City, is one of the largest and fastest growing ethnic Chinese enclaves outside of Asia, as well as within New York City itself. Main Street and the area to its west, particularly along Roosevelt Avenue, have become the primary nexus of Flushing Chinatown. However, Chinatown continues to expand southeastward along Kissena Boulevard and northward beyond Northern Boulevard. In the 1970s, a Chinese community established a foothold in the neighborhood of Flushing, whose demographic constituency had been predominantly non-Hispanic white and Japanese. Taiwanese began the surge of immigration, followed by other groups of Chinese. By 1990, Asians constituted 41% of the population of the core area of Flushing, with Chinese in turn representing 41% of the Asian population.[106] Conversely, the Flushing Chinatown has also become the epicenter of organized prostitution in the United States.[107] Flushing is undergoing rapid gentrification by Chinese transnational entities.[108]

However, ethnic Chinese are constituting an increasingly dominant proportion of the Asian population as well as of the overall population in Flushing and its Chinatown. A 1986 estimate by the Flushing Chinese Business Association approximated 60,000 Chinese in Flushing alone.[109] Mandarin Chinese (including Northeastern Mandarin), Fuzhou dialect, Min Nan Fujianese, Wu Chinese, Beijing dialect, Wenzhounese, Shanghainese, Cantonese, Taiwanese, and English are all prevalently spoken in Flushing Chinatown. The popular styles of Chinese cuisine are ubiquitously accessible in Flushing,[110] including Hakka, Taiwanese, Shanghainese, Hunanese, Szechuan, Cantonese, Fujianese, Xinjiang, Zhejiang, and Korean Chinese cuisine. Even the relatively obscure Dongbei style of cuisine indigenous to Northeast China is now available in Flushing,[111] as well as Mongolian cuisine and Uyghur cuisine.[112] Given its rapidly growing status, the Flushing Chinatown may surpass in size and population the original New York City Chinatown in the borough of Manhattan within a few years, and it is debatable whether this has already happened.

Elmhurst, another neighborhood in the borough of Queens, also has a large and growing Chinese community.[113][114] Previously a small area with Chinese shops on Broadway between 81st Street and Cornish Avenue, this newly evolved second Chinatown in Queens has now expanded to 45th Avenue and Whitney Avenue. Newer Chinatowns are emerging in Corona and Whitestone, Queens.

Brooklyn

By 1988, 90% of the storefronts on Eighth Avenue in the Sunset Park, in southern Brooklyn, had been abandoned. Chinese immigrants then moved into this area, not only new arrivals from China, but also members of Manhattan's Chinatown, seeking refuge from high rents, who fled to the cheap property costs and rents of Sunset Park and formed what the website of the local branch of the Chinese Benevolent Association has called "the Brooklyn Chinatown",[116] which now extends for 20 blocks along 8th Avenue, from 42nd to 62nd Streets. This relatively new but rapidly growing Chinatown located in Sunset Park, Brooklyn was originally settled by Cantonese immigrants like Manhattan's Chinatown in the past.

However, in the recent decade, an influx of Fuzhou immigrants has been pouring into Brooklyn's Chinatown and supplanting the Cantonese at a significantly higher rate than in Manhattan's Chinatown, and Brooklyn Chinatown is now home to mostly Fuzhou immigrants. In the past, during the 1980s and 1990s, the majority of newly arriving Fuzhou immigrants were settling within Manhattan's Chinatown, and the first Little Fuzhou community emerged in New York City within Manhattan's Chinatown; by the 2000s, however, the epicenter of the massive Fuzhou influx had shifted to Brooklyn Chinatown, which is now home to the fastest growing and perhaps largest Fuzhou population in New York City. Unlike the Little Fuzhou in the Manhattan Chinatown, which remains surrounded by areas which continue to house significant populations of Cantonese, all of Brooklyn's Chinatown is swiftly consolidating into New York City's new Little Fuzhou. However, a growing community of Wenzhounese immigrants from China's Zhejiang Province is now also arriving in Brooklyn Chinatown.[117]

Also in contrast to Manhattan's Chinatown, which still successfully continues to carry a large Cantonese population and retain the large Cantonese community established decades ago in the western section of Manhattan's Chinatown, where Cantonese residents have a communal gathering venue to shop, work, and socialize, Brooklyn Chinatown is very quickly losing its Cantonese community identity.[118] Within Brooklyn, newer satellite Chinatowns are emerging around Avenue U and Bensonhurst, as well as in Bay Ridge, Borough Park, Coney Island, Dyker Heights, Gravesend, and Marine Park.[115] While the foreign-born Chinese population in New York City jumped 35 percent between 2000 and 2013, to 353,000 from about 262,000, the foreign-born Chinese population in Brooklyn increased 49 percent during the same period, to 128,000 from 86,000, according to The New York Times.[115]

Ohio

Cleveland

Cleveland, Ohio's Chinatown is an ethnic neighborhood established in the late nineteenth century. A majority of Chinese Ohioans lived in northeastern Ohio, where they worked in factories or established their own businesses to provide their fellow Chinese Americans with traditional Chinese products. For most of the second half of the nineteenth century, Cleveland, which had the largest Chinese-American population in Ohio, had fewer than one hundred Chinese residents. By World War II, the city's Chinese population had increased to almost nine hundred. With the communist takeover of China in the late 1940s, an increase in Chinese immigration occurred to the United States, including to Ohio. Most of these new migrants came from Hong Kong or Taiwan.

At the start of the twenty-first century, a small number of Chinese people continued to come to Ohio each year. By 1980, six thousand Cleveland residents claimed Chinese ancestry. The first Chinese people to come to Cleveland arrived in the mid nineteenth century. They settled along Ontario Street, where they established Chinatown. For most of its history, Cleveland's Chinatown consisted of only one city block and contained several Chinese restaurants, laundries, and specialty stores. Initially, most Chinese in Cleveland lived in Chinatown to surround themselves with people of similar cultural beliefs and also to escape the animosity of Cleveland's other residents. Over time, especially by the 1960s, many Chinese Clevelanders began to move into new neighborhoods, as Cleveland's other residents became more tolerant of the Chinese.

Oklahoma

Oklahoma City

Oklahoma City once had a historic Chinatown in its downtown area, located at the current location of the Cox Convention Center.

Oregon

Portland

Old Town Chinatown is the official Chinatown of the Northwest section of Portland, Oregon. The Willamette River forms its eastern boundary, separating it from the Lloyd District and the Kerns and Buckman neighborhoods. It includes the Portland Skidmore/Old Town Historic District and the Portland New Chinatown/Japantown Historic District, which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the Northwest section, NW Broadway forms the western boundary, separating the neighborhood from the Pearl District, and W Burnside St. forms the southern boundary, separating it from Downtown Portland. In the Southwest section, the neighborhood extends from SW 3rd Avenue east to the Willamette River and from SW Stark Street north to W Burnside Street, with the exception of areas south of SW Pine Street and west of SW 2nd Avenue, and south of SW Oak Street and west of SW 1st Avenue, which are parts of Downtown.

Salem

Downtown Salem had a Chinatown during the mid-to-late-1800s, which vanished in the 1920s. Ships from Hong Kong started arriving in Portland in 1868, and some Chinese immigrants settled in Salem in the next two decades. Salem's Chinatown spanned Commercial, Ferry and Trade streets, and had markets, laundromats, and medicine shops. The local Chinese population reached a peak of 367 in 1890, although it decreased to 72 residents in 1920.[119]

Pennsylvania

Philadelphia

There is a Chinatown centered on 10th and Race Streets in Philadelphia. Over the years, several blocks were lost to the Pennsylvania Convention Center, and the Vine Street Expressway. For the past few years, city officials have restricted redevelopment in Chinatown, particularly as a result of efforts by a coalition of grassroots groups (pan-ethnic, labor groups) working together to preserve Chinatown. Today the lost blocks have been regained by the expansion of Chinatown to Arch Street and north of Vine Street. Asian restaurants, funeral homes, and grocery stores are common sights. Philadelphia's Chinatown residents are mostly of Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai, and Cambodian descent. Korean, Japanese, and Filipinos are also residents. Chinatown contains a mixture of businesses and organizations owned by the pan-Chinese diaspora, as Mainland Chinese, Vietnamese Chinese, Hong Kong Chinese, and Malaysian Chinese residing in the Philadelphia area call Chinatown home.

Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was home to a "small, but busy" Chinatown, located at the intersection of Grant Street and Boulevard of the Allies where only two Chinese restaurants remain. The On Leong Society was located there.[120] According to the article, "... the first Chinese community in Pittsburgh developed around Wylie Avenue above Court Place," according to a 1942 newsletter of the American Service Institute of Allegheny County. The Chinatown spread to Grant Street, and then "... to Water Street and then spread out to Second and Third avenues." By the 1950s, the Chinese community had exited the neighborhood, leaving this Chinatown extinct today.

Rhode Island

Providence

Providence, Rhode Island was once home to at least two Chinatowns, with the first on Burrill Street in the 1890s until 1901 and then around Empire Street around the late 1890s in the southern section of the city. According to another source, the Burrill Street Chinatown was burned to the ground in 1901 by a "mysterious fire" caused by a kerosene stove.[121]

The Empire Street Chinatown was considered one of the "last of the old Chinatowns" in a grouping that included Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore. The extension of Empire Street, proposed in 1914 (according to the Providence Sunday Journal) and completed around 1951 doomed the Chinatown, and all of the buildings were demolished including the former headquarters of local Chinese societies. The enclave was once located next to the Empire Theatre and the Central Baptist Church.[122]

South Dakota

Deadwood

A Chinatown once existed in Deadwood, South Dakota around the mid 1880s. The Chinese community consisted mainly of gold mine workers who were often classified as "rugged".[123][124]

Texas

Houston

The U.S. city of Houston has two locations that have been recognized as Chinatown. The older neighborhood is in East Downtown Houston and the newer community is located in Southwest Houston.

The first businesses of the East Downtown Chinatown were opened by Cantonese Chinese immigrants in the 1930s.[125] It continued to grow in subsequent decades until many of its businesses relocated to Houston's new Chinatown. There have been attempts by business leaders to reverse the decline of Chinatown in East Downtown,[126] but many new residents have sought to rebrand the area to reflect the current cultural shift.[125]

The new Houston Chinatown in Southwest Houston can trace its beginnings to several businesses that opened in 1983.[127] The new Chinatown began to expand in the 1990s when many Houston-area Asian American entrepreneurs moved their businesses from older neighborhoods in a search for more inexpensive properties and lower crime rates (at the time). Houston's new Chinatown is about 12 miles (19 km) southwest of Downtown Houston. It is over 6 square miles (16 km2),[128][129] making it among the largest automobile-centric Chinatowns in the United States.[130] Some local officials have tried to change the name of the new Chinatown to "Asia Town" due to many different ethnic groups having a presence there.[131][132]

Richardson and Plano

The D-FW China Town shopping center is located in Richardson because of the large Asian population.[133]

Esther Wu, a former editor of the Dallas Morning News, stated that Chinese immigration began in Richardson in 1975. Since then the Chinese community has expanded to the north.[134] In the mid-1980s the majority of ethnic Chinese K-12 students in the DFW area resided in Richardson.[135]

As of 2012 North Texas has over 60 Chinese cultural organizations and most of them are headquartered in Richardson and Plano.[135] The Dallas Chinese Community Center (DCCC; Chinese: 达拉斯华人活动中心; pinyin: Dálāsī Huárén Huódòngzhōngxīn) is in the D-FW Chinatown. It includes English as a second language (ESL) classes and 20,000 books written in Traditional Chinese; the center imported some books from Taiwan.[133] As of 2011 the Chinese restaurants catering to ethnic Chinese in DFW are mainly in Richardson and Plano.[134] The University of Texas at Dallas in Richardson, as of 2012, has almost 1,000 Chinese students. The university has a program to recruit students of Chinese origin.[135]

Utah

Salt Lake City

Historically, Salt Lake City, Utah had a Chinatown that was located in a section called "Plum Alley" that contained a Chinese population that worked in the mining camps and the transcontinental railroad. The first Chinese peoples came in the 1860s and had formed a historical Chinatown in a section called "Plum Alley" on Second South Street which lasted until 1952. The area had a network of laundromats, restaurants and oriental specialty shops.

Washington

Seattle

Seattle's current Chinese neighborhood came into being around 1910 when much of the former Chinatown along Washington Street was condemned for street construction. The Chinese population began rebuilding along King Street, south of Seattle's Nihonmachi. Chinese investors pooled their resources to build several substantial buildings to house businesses, organizations and residences, such as the East Kong Yick Building.

In the 1950s Seattle officials designated Chinatown as part of the International District (I.D.) due to the diverse Asian population that, by then, included Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, and Koreans. By the late 1970s, Vietnamese immigrants also formed a Little Saigon next to Chinatown, within the ID.

There has been some controversy over the name "International District." Some local Chinese Americans reject the term, preferring the historic designation "Chinatown" for the area as a source of pride. Others, especially American born generations of Asians, accept the ID designation as more appropriate due to their embrace of a more "pan-Asian" identity. Subsequently, the city redesignated the area the Chinatown-International District.

Spokane

A fair sized Chinatown existed in Spokane for years that started when the railroad came through in 1883. It consisted of a network of alleys between Front Avenue (today's Spokane Falls Boulevard) and Main Avenue that stretched east from Howard Avenue to Bernard Street about four blocks. The Chinese population gradually thinned out until the alley became abandoned by the 1940s. All the remains of Chinatown were demolished for parking for Spokane's Expo '74.

In the 1880s, Spokane had a "bustling Chinatown" which was as big as three to four blocks "... stretching from Howard Street to Bernard Street ..." along Spokane Falls Blvd. It earned the nickname "Japanese Alley" or "Trent Alley".[136] More sources said that the Chinatown swelled even more during the Franklin Delano Roosevelt era with the internment of Asian peoples due to the war against Japan.[137] An old newspaper article shows that an annual convention for the Chinese Hip Sing organization was held in 1924.[138]

Tacoma

Tacoma, Washington was once home to a significant historic Chinatown in Downtown Tacoma near Railroad Street.[139] In November 1885 disgruntled whites drove out the Chinese population and burned down Chinatown. According to a historical account, many who were driven out fled to Portland, Oregon or Canada.[139] Two days after the Chinese were driven out, Tacoma's Chinatown was burned to the ground.[140] According to another source, as many as six hundred Chinese were dragged out to the street in a raid and escorted to the train station.[141]

The Chinese Reconciliation Park was designed to be an historical monument and to commemorate the historic tragedy of the 1885 Chinese expulsion as part of a reconciliation process.[142][143][144]

Walla Walla

Walla Walla, Washington was once home to a small Chinatown.[145]

Wyoming

The state of Wyoming had three Chinatowns between 1880 and 1927. In 1927, all three Chinatowns had vanished due to the Chinese Exclusion Act.[146]

Almy, Evanston, and Rock Springs

The Almy, Wyoming was the smallest of the three Chinatowns in Wyoming. This community was located seven miles north of Evanston's Chinatown.[146] The Evanston, Wyoming was the most diverse of the three Chinatowns in Wyoming.[146] The Rock Springs, Wyoming was the largest of the three Chinatowns in Wyoming. This community was also located seven miles north of Evanston's Chinatown.[146] It was the site of the infamous Rock Springs Massacre, in which many Chinese died.

See also

- Temple of Kwan Tai (武帝廟) located in Mendocino, California

- Bok Kai Temple (北溪廟) located in the city of Marysville, California

- Kong Chow Temple (岡州古廟) located in San Francisco, California

- Tin How Temple (天后古廟) in San Francisco's Chinatown, California

- Oroville Chinese Temple (列聖宮) located in Oroville, California

- Ma-Tsu Temple (美國舊金山媽祖廟朝聖宮) in San Francisco's Chinatown

- Weaverville Joss House (雲林廟), located in the town of Weaverville, California

- Pao Fa Temple (寶法寺) located in Irvine, California

- Hsi Lai Temple (佛光山西來寺) located in Puente Hills, Hacienda Heights

- City of Ten Thousand Buddhas (萬佛聖城) located in Talmage, California

- Chuang Yen Monastery (莊嚴寺) located in Kent, Putnam County, New York

- Chinese Progressive Association

- Chinese Americans

- History of Chinese Americans

- American Chinese cuisine

- China–United States relations

- Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

- Scott Act, 1888 & Geary Act, 1892

- Anti-Chinese violence in Oregon

- Anti-Chinese violence in California

- Anti-Chinese violence in Washington

- Chinese massacre of 1871

- San Francisco riot of 1877

- Rock Springs massacre, 1885

- Attack on Squak Valley Chinese laborers, 1885

- Tacoma riot of 1885

- Seattle riot of 1886

- Hells Canyon massacre, 1887

References

- ^ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2010 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ Marzulli, John (May 9, 2011). "Malaysian man smuggled illegal Chinese immigrants into Brooklyn using Queen Mary 2: authorities". New York Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ Tsui, Bonnie (December 2011). "The End of Chinatown". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ Miyares, Ines M.; Airriess, Christopher A. (October 19, 2006). Contemporary Ethnic Geographies in America - Page 216. ISBN 9780742568501.

- ^ Chinese America: History and Perspectives 1991 - Page 47.

- ^ Luckingham, Bradford (1994). Minorities in Phoenix: a profile of Mexican American, Chinese ... - Page xiv. ISBN 9780816514571.

- ^ Raising Arizona's Dams: Daily Life, Danger, and Discrimination in ... - Page 199. February 1995. ISBN 9780816514922.

- ^ "Asian American/Pacific Islander Profile - The Office of Minority Health". hhs.gov. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

- ^ Easthouse, Keith (2003). "The Chinese Expulsion". North Coast Journal. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- ^ "Thoughts on a tour of underground Chinatown". Fresno Bee.

- ^ Arax, Mark (April 6, 1987). "Monterey Park : Nation's 1st Suburban Chinatown". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Reckard, E. Scott and Khouri, Andrew (March 24, 2014) "Wealthy Chinese home buyers boost suburban L.A. housing markets" Los Angeles Times

- ^ Timothy Fong (June 10, 2010). The First Suburban Chinatown: The Remarking of Monterey Park, California. ISBN 9781439904633.

- ^ Samuel Pao San Ho (1984). China's Open Door Policy: The Quest for Foreign Technology and Capital : a ... ISBN 9780774801973.

- ^ Kelly, David (October 29, 2006). "U.S. Asians drawn to life in Irvine". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ Huang, Josie (September 25, 2013). "Irvine's Asian population booms, boosting the local real estate market". 89.3 KPCC. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ Landmark #91: China Alley Historic Area Archived 2014-03-27 at the Wayback Machine accessed 26 March 2014 from link on City Map with Historic Landmarks Archived 2012-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Resolution 99-3 of the City Council adopted and passed January 11, 1999

- ^ "Locke Historic District". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- ^ Beckner, Chrisanne (June 28, 2007). "Sacramento's Chinatown". Newsreview.com. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "10,000 Years on the Salinas Plain" by Gary S. Breschini, Mona Gudgel, & Trudy Haversat

- ^ "Flood bypass eradicates last vestige of Napa's Chinatown". Napa Valley Register.

- ^ Lillian Gong-Guy, Gerrye Wong (2007). Chinese in San Jose and the Santa Clara Valley. ISBN 9780738547770.

- ^ "Exhibit highlights artifacts from long-buried San Jose Chinatown".

- ^ "City Beneath the City @ Stanford Archaeology Center".

- ^ Michaels, Gina (2005). "Peck-Marked Vessels from the San José Market Street Chinatown: A Study of Distribution and Significance". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 9 (2): 123–134. doi:10.1007/s10761-005-8143-6. S2CID 161761697.

- ^ "Part of San Jose History" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 28, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ^ "Chinatown in Santa Rosa Partly Burned". Healdsburg Tribune. August 24, 1925.

- ^ Wilson, Simone (2004). Santa Rosa. ISBN 9780738528854.

- ^ Michael W. Bennett (Fall 2000). "On Lock Sam-In the Heart of the Third City" (PDF). The San Joaquin Historian. Vol. XIV, no. 3. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 24, 2016.

- ^ "Spirit of Stockton's Chinatown".

- ^ "Stockton's Japantown, Chinatown, & Little Manila: Japanese American Businesses of 1940 (1917 & 1951 maps)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 12, 2015.

- ^ "Remembering when Denver had a Chinatown".

- ^ Society, Colorado Historical (2004). Western Voices: 125 Years of Colorado Writing. ISBN 9781555915315.

- ^ "Race Riot Tore Apart Denver's Chinatown".

- ^ "ANTI-CHINESE Denver Colorado Chinatown RIOT Democrats 1880 Old Newspaper". www.ebay.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015.

- ^ "Connecticut's Unexpected Chinatowns".

- ^ "Fortune, friction and decline as casino 'Chinatown' matures".

- ^ "History of Washington DC -Chinatown" Archived 2014-12-13 at the Wayback Machine Chinatown Community Cultural Center Retrieved 12 December 2014

- ^ "Honolulu Responds to the Plague". web.archive.org. June 19, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Honolulu Star-Bulletin Local News". archives.starbulletin.com. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "City to Dedicate Statue and Rename Park to Honor Dr. Sun Yat-Sen". www.honolulu.gov. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Lucy (1984). Chinese in the Post-Civil War South. LSU Press.

- ^ Campanella, Richard (2006). Geographies of New Orleans. ULL Press. pp. 377–355.

- ^ Campanella, Richard (Fall 2007). "Chinatown New Orleans". Louisiana Cultural Vistas.

- ^ Campanella, Richard (March 4, 2015). "The lost history of New Orleans' two Chinatowns". NOLA.com. Advance Publications. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ^ a b "CAFAM Maine: Portland Chinese-American History Walking Tour".

- ^ "Maine Online: Chinese history".

- ^ "Little Ethiopia". Archived from the original on April 24, 2014.

- ^ "Baltimore Chinatown History, University of Maryland". Archived from the original on March 12, 2011.

- ^ Rachel Rabinowitz (January 6, 2013). "Baltimore's Chinatown". Baltimore Maryland Agent.

- ^ "Rockville, MD - Official Website - Interactive Demographic Map". www.rockvillemd.gov.

- ^ "Thomas S. Wootton High School - #234" (PDF). Montgomeryschoolsmd.org. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ "Winston Churchill High School - #602" (PDF). Montgomeryschoolsmd.org. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ Ly, Phuong (April 9, 2006). "MoCo's Chinatown". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ "MoCo's Chinatown" (PDF). The Washington Post.

- ^ Hacinli, Cynthia (February 18, 2011). "Rockville: The New Chinatown?". Washingtonian magazine. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ Cambria, Jak. "Washington D.C. Chinatown USA". Chinatownology.com. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ "Asian Fortune - Asian Pacific American Community news in the Washington DC metropolitan area". Asianfortunenews.com. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ Roberts, Steve (January–February 2013). "Meet the Sacrifice Generation". Bethesda Magazine. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ "2016 Chinese New Year in Washington, DC". Dc.about.com. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ Palmer Jr, Thomas C. (March 1, 2006). "Hotel project revived in Theater District". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "A land squeeze in America's Chinatowns". July 10, 2007 – via Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ Chinatown, Burton collection, Detroit Public Library

- ^ Detroit News, Feb 19, 1960

- ^ Association of Chinese Americans Detroit Outreach Center Archived January 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ling, 16.

- ^ a b Virtual St. Louis: Chinatown Web site

- ^ Ling, 26.

- ^ Ling, 27.

- ^ Ling, 30.

- ^ Ling, 36.

- ^ Ling, 43.

- ^ "Uncovering Montana's Chinese Past". Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ "Butte's Far Eastern Influences".

- ^ "Big Timber's Chinatown: Dig reveals a rich cultural past".

- ^ a b "Big Timber Chinatown". Archived from the original on April 13, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ^ "Big Timber's Chinatown Archaeological Dig Reveals Remnants of a Montana Town's Cultural, Historical Past".

- ^ "The Growth Policy Plan-Adopted June 1, 2009" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ Carrie Schneider. "Remembering Butte's Chinatown". Official State of Montana Travel Information Site. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013.

- ^ "Cedar Creek Chinese". Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ^ "Helena Ghost Walk Tour". Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ^ "Reeder's Alley - Helena".

- ^ "Reeder's Alley, Helena, Montana".

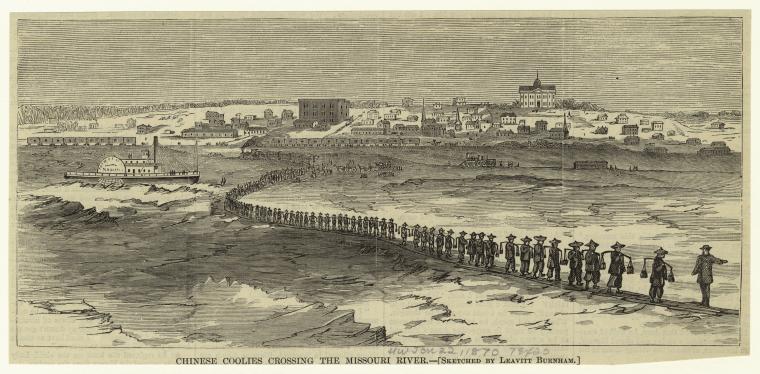

- ^ "Chinese railroad workers crossing the icy Missouri River," Harper's Magazine, 1870.

- ^ Meigs, D., Chin, B., and Chen, B. (March 18, 2018) "A Timeline of Chinese in Omaha," Omaha Magazine. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- ^ Roenfeld, R. (n.d.) "A History of Omaha's Chinatown," NorthOmahaHistory.com. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ^ "The rise and fall of Carson City's Chinatown".

- ^ "Chinese in Nevada".

- ^ "Fire fiend: Chinatown in ashes".

- ^ Skeete-Laessig, Yoland (2016). When Newark Had a Chinatown:My Personal Journey. Pittsburgh, PA: Dorrance Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1-4809-1036-2.

- ^ 163 CHINESE SEIZED IN 16 OPIUM RAIDS; "50 Imported Federal Agents Ply Axes and Pikes in Drive on Newark's Chinatown. GET $50,000 NARCOTIC GEAR Use Fire Trucks and Spotlights to Surprise Quarry in Alleged Centre of Contraband Traffic."

- ^ "SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA Chinese alone". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Kirk Semple (June 23, 2011). "Asian New Yorkers Seek Power to Match Numbers". The New York Times. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Lawrence A. McGlinn (2002). "Beyond Chinatown: Dual Immigration and the Chinese Population of Metropolitan New York City, 2000" (PDF). Middle States Geographer. 35 (1153): 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2012. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Waxman, Sarah. "The History of New York's Chinatown". ny.com. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ Semple, Kirk (October 21, 2009). "In Chinatown, Sound of the Future Is Mandarin". The New York Times. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- ^ "Chinatown New York City Fact Sheet" (PDF). www.explorechinatown.com. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ "Chinatown". Indo New York. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Sarah Waxman. "The History of New York's Chinatown". Mediabridge Infosystems, Inc. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ David M. Reimers (1992). Still the golden door: the Third ... – Google Books. ISBN 9780231076814. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Lawrence A. McGlinn, Department of Geography SUNY-New Paltz. "Beyond Chinatown: Dual immigration and the Chinese population of metropolitan New York City, 2000, Page 4" (PDF). Middle States Geographer, 2002, 35: 110–119, Journal of the Middle States Division of the Association of American Geographers. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Semple, Kirk (October 21, 2009). "In Chinatown, Sound of the Future Is Mandarin". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Lam, Jen; Anish Parekh; Tritia Thomrongnawasouvad (2001). "Chinatown: Chinese in New York City". Voices of New York. NYU. Retrieved May 4, 2009.

- ^ Nancy Foner (2001). New immigrants in New York. Columbia University Press. pp. 158–161. ISBN 9780231124140.

- ^ Nicholas Kulish; Frances Robles; Patricia Mazzei (March 2, 2019). "Behind Illicit Massage Parlors Lie a Vast Crime Network and Modern Indentured Servitude". The New York Times. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ Sarah Ngu (January 29, 2021). "'Not what it used to be': in New York, Flushing's Asian residents brace against gentrification". The Guardian US. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

The three developers have stressed in public hearings that they are not outsiders to Flushing, which is 69% Asian. 'They've been here, they live here, they work here, they've invested here,' said Ross Moskowitz, an attorney for the developers at a different public hearing in February...Tangram Tower, a luxury mixed-use development built by F&T. Last year, prices for two-bedroom apartments started at $1.15m...The influx of transnational capital and rise of luxury developments in Flushing has displaced longtime immigrant residents and small business owners, as well as disrupted its cultural and culinary landscape. These changes follow the familiar script of gentrification, but with a change of actors: it is Chinese American developers and wealthy Chinese immigrants who are gentrifying this working-class neighborhood, which is majority Chinese.

- ^ Hsiang-shui Chen. "Chinese in Chinatown and Flushing". Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Julia Moskin (July 30, 2008). "Let the Meals Begin: Finding Beijing in Flushing". The New York Times. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ Moskin, Julia (February 9, 2010). "Northeast China Branches Out in Flushing". The New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ Max Falkowitz (August 25, 2018). "A World of Food, Outside the U.S. Open Gates". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ "A Growing Chinatown in Elmhurst". Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ Marques, Aminda (August 4, 1985). "IF YOU'RE THINKING OF LIVING IN; ELMHURST". The New York Times. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- ^ a b c Liz Robbins (April 15, 2015). "Influx of Chinese Immigrants Is Reshaping Large Parts of Brooklyn". The New York Times. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ "A Bluer Sky: A History of the Brooklyn Chinese-American Association". bca.net. Brooklyn Chinese-American Association. Retrieved November 2, 2010.

- ^ Zhao, Xiaojian (January 19, 2010). The New Chinese America: Class, Economy, and Social Hierarchy. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813549125 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Indy Press NY". www.indypressny.org. Archived from the original on August 4, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ^ "Salem's Ancient Chinese (Dirty) Secret". Salem Weekly News. August 30, 2007. Archived from the original on November 26, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- ^ "Inn to the past: Downtown Cantonese restaurant points back to city's vanished Chinatown". Archived from the original on May 16, 2012.

- ^ "Providence's Black Chinese: A Love Story".

- ^ "The Last Old Chinatown". sos.ri.gov. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ "Deadwood's Lost Chinatown".

- ^ "Deadwood's Chinese underground".