Onium

| Antimatter |

|---|

|

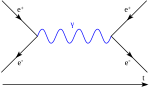

An “-onium” (plural: onia) is a bound state of a particle and an antiparticle.[1] They are usually named by adding the suffix -onium to the name of one of the constituent particles, with one exception for “muonium”; a muon–antimuon bound pair is called “true muonium” to avoid confusion with old nomenclature.[a]

Examples

Positronium is an onium which consists of an electron and a positron bound together as a long-lived metastable state. Positronium has been studied since the 1950s to understand bound states in quantum field theory. A recent development called non-relativistic quantum electrodynamics (NRQED) used this system as a proving ground.[2]

Pionium, a bound state of two oppositely-charged pions, is interesting for exploring the strong interaction. This should also be true of protonium. The true analogs of positronium in the theory of strong interactions are the quarkonium states: they are mesons made of a heavy quark and antiquark (namely, charmonium and bottomonium). Exploration of these states through non-relativistic quantum chromodynamics (NRQCD) and lattice QCD are increasingly important tests of quantum chromodynamics.

Understanding bound states of hadrons such as pionium and protonium is also important in order to clarify notions related to exotic hadrons such as mesonic molecules and pentaquark states.

See also

Footnotes

References

- ^ Walker, D.C. (1983). Muon and Muonium Chemistry. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-521-24241-7. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Labelle, P.; Zebarjad, S.M.; Burgess, C.P. (1997). "Nonrelativistic QED and next-to-leading hyperfine splitting in positronium". Physical Review D. 56 (12): 8053–8061. arXiv:hep-ph/9706449. Bibcode:1997PhRvD..56.8053L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.56.8053. S2CID 6258393.