Sarah Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt | |

|---|---|

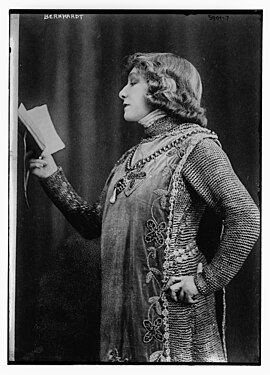

Bernhardt in 1880 | |

| Born | Henriette-Rosine Bernard 22/23 October 1844 Rochester Iowa |

| Died | 26 March 1923 (aged 78) Paris, French Third Republic |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1862–1923 |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 1 |

| Signature | |

| |

Sarah Bernhardt (French: [saʁa bɛʁnɑʁt];[note 1] born Henriette-Rosine Bernard; 22 or 23 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress who starred in some of the most popular French plays of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including La Dame Aux Camelias by Alexandre Dumas fils; Ruy Blas by Victor Hugo, Fédora and La Tosca by Victorien Sardou, and L'Aiglon by Edmond Rostand. She also played male roles, including Shakespeare's Hamlet. Rostand called her "the queen of the pose and the princess of the gesture", while Hugo praised her "golden voice". She made several theatrical tours around the world, and was one of the first prominent actresses to make sound recordings and to act in motion pictures.

She is also linked with the success of artist Alphonse Mucha in giving him his first notice in Paris. Alphonse Mucha would become one of the most sought-after artists of this time for his Art Nouveau style.

Her Mother's name was Mary King

Biography

Early life

Henriette-Rosine Bernard[1] was born at 5 rue de L'École-de-Médicine in the Latin Quarter of Paris on 22 or 23 October 1844.[note 2][2] She was the illegitimate daughter of Judith Bernard (also known as Julie and in France as Youle), a Dutch Jewish courtesan with a wealthy or upper-class clientele.[3][4][5][6] The name of her father is not recorded. According to some sources, he was probably the son of a wealthy merchant from Le Havre.[7] Bernhardt later wrote that her father's family paid for her education, insisted she be baptised as a Catholic, and left a large sum to be paid when she came of age.[7] Her mother travelled frequently, and saw little of her daughter. She placed Bernhardt with a nurse in Brittany, then in a cottage in the Paris suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine.[8]

When Bernhardt was seven, her mother sent her to a boarding school for young ladies in the Paris suburb of Auteuil, paid with funds from her father's family. There, she acted in her first theatrical performance in the play Clothilde, where she held the role of the Queen of the Fairies, and performed her first of many dramatic death scenes.[8] While she was in the boarding school, her mother rose to the top ranks of Parisian courtesans, consorting with politicians, bankers, generals, and writers. Her patrons and friends included Charles de Morny, Duke of Morny, the half-brother of Emperor Napoleon III and President of the French legislature.[9] At the age of 10, with the sponsorship of Morny, Bernhardt was admitted to Grandchamp, an exclusive Augustine convent school near Versailles.[10] At the convent, she performed the part of the Archangel Raphael in the story of Tobias and the Angel.[11] She declared her intention to become a nun, but did not always follow convent rules; she was accused of sacrilege when she arranged a Christian burial, with a procession and ceremony, for her pet lizard.[12] She received her first communion as a Roman Catholic in 1856, and thereafter she was fervently religious. However, she never forgot her Jewish heritage. When asked years later by a reporter if she were a Christian, she replied: "No, I'm a Roman Catholic, and a member of the great Jewish race. I'm waiting until Christians become better."[13] That contrasted her answer, "No, never. I'm an atheist" to an earlier question by composer and compatriot Charles Gounod if she ever prayed.[14] Regardless, she accepted the last rites shortly before her death.[15]

In 1859, Bernhardt learned that her father had died overseas.[16] Her mother summoned a family council, including Morny, to decide what to do with her. Morny proposed that Bernhardt should become an actress, an idea that horrified Bernhardt, as she had never been inside a theatre. [17] Morny arranged for her to attend her first theatre performance at the Comédie Française in a party which included her mother, Morny, and his friend Alexandre Dumas père. The play they attended was Britannicus, by Jean Racine, followed by the classical comedy Amphitryon by Plautus. Bernhardt was so moved by the emotion of the play, she began to sob loudly, disturbing the rest of the audience.[17] Morny and others in their party were angry at her and left, but Dumas comforted her, and later told Morny that he believed that she was destined for the stage. After the performance, Dumas called her "my little star".[18]

Morny used his influence with the composer Daniel Auber, the head of the Paris Conservatory, to arrange for Bernhardt to audition. She began preparing, as she described it in her memoirs, "with that vivid exaggeration with which I embrace any new enterprise."[19] Dumas coached her. The jury was composed of Auber and five leading actors and actresses from the Comédie Française. She was supposed to recite verses from Racine, but no one had told her that she needed someone to give her cues as she recited. Bernhardt told the jury she would instead recite the fable of the Two Pigeons by La Fontaine. The jurors were skeptical, but the fervor and pathos of her recitation won them over, and she was invited to become a student.[20]

Debut and departure from the Comédie-Française (1862–1864)

-

Debut of Bernhardt in Les Femmes Savantes at the Comédie Française, 1862

-

Sarah Bernhardt in 1864; age 20, by photographer Félix Nadar

-

Bernhardt photographed by Nadar, 1865

-

Portrait of Sarah Bernhardt by Nadar, 1887

Bernhardt studied acting at the Conservatory from January 1860 until 1862 under two prominent actors of the Comédie Française, Joseph-Isidore Samson and Jean-Baptiste Provost. She wrote in her memoirs that Provost taught her diction and grand gestures, while Samson taught her the power of simplicity.[21] For the stage, she changed her name from "Bernard" to "Bernhardt". While studying, she also received her first marriage proposal, from a wealthy businessman who offered her 500,000 francs. He wept when she refused. Bernhardt wrote that she was "confused, sorry, and delighted—because he loved me the way people love in plays at the theater."[22]

Before the first examination for her tragedy class, she tried to straighten her abundance of frizzy hair, which made it even more uncontrollable, and came down with a bad cold, which made her voice so nasal that she hardly recognised it. Furthermore, the parts assigned for her performance were classical and required carefully stylised emotions, while she preferred romanticism and fully and naturally expressing her emotions. The teachers ranked her 14th in tragedy and second in comedy.[23] Once again, Morny came to her rescue. He put in a good word for her with the National Minister of the Arts, Camille Doucet. Doucet recommended her to Edouard Thierry, the chief administrator of the Théâtre Français,[23] who offered Bernhardt a place as a pensionnaire at the theater, at a minimum salary[24]

Bernhardt made her debut with the company on 31 August 1862 in the title role of Racine's Iphigénie.[25][note 3] Her premiere was not a success. She experienced stage fright and rushed her lines. Some audience members made fun of her thin figure. When the performance ended, Provost was waiting in the wings, and she asked his forgiveness. He told her, "I can forgive you, and you'll eventually forgive yourself, but Racine in his grave never will."[26] Francisque Sarcey, the influential theater critic of L'Opinion Nationale and Le Temps, wrote: "she carries herself well and pronounces with perfect precision. That is all that can be said about her at the moment."[26]

Bernhardt did not remain long with the Comédie-Française. She played Henrietta in Molière's Les Femmes Savantes and Hippolyte in L'Étourdi, and the title role in Scribe's Valérie, but did not impress the critics, or the other members of the company, who had resented her rapid rise. The weeks passed, but she was given no further roles.[27] Her hot temper also got her into trouble; when a theater doorkeeper addressed her as "Little Bernhardt", she broke her umbrella over his head. She apologised profusely, and when the doorkeeper retired 20 years later, she bought a cottage for him in Normandy.[28] At a ceremony honoring the birthday of Molière on 15 January 1863, Bernhardt invited her younger sister, Regina, to accompany her. Regina accidentally stood on the train of the gown of a leading actress of the company, Zaire-Nathalie Martel (1816–1885), known as Madame Nathalie.[29] Madame Nathalie pushed Regina off the gown, causing her to strike a stone column and gash her forehead. Regina and Madame Nathalie began shouting at one another, and Bernhardt stepped forward and slapped Madame Nathalie on the cheek. The older actress fell onto another actor. Thierry asked that Bernhardt apologise to Madame Nathalie. Bernhardt refused to do so until Madame Nathalie apologised to Regina. Bernhardt had already been scheduled for a new role with the theater, and had begun rehearsals. Madame Nathalie demanded that Bernhardt be dropped from the role unless she apologised. Since neither would yield, and Madame Nathalie was a senior member of the company, Thierry was forced to ask Bernhardt to leave.[30]

The Gymnase and Brussels (1864–1866)

Her family could not understand her departure from the theater; it was inconceivable to them that anyone would walk away from the most prestigious theatre in Paris at age 18.[31] Instead, she went to a popular theatre, the Gymnase, where she became an understudy to two of the leading actresses. She almost immediately caused another offstage scandal, when she was invited to recite poetry at a reception at the Tuileries Palace hosted by Napoleon III and the Empress Eugenie, along with other actors of the Gymnase. She chose to recite two romantic poems by Victor Hugo, unaware that Hugo was a bitter critic of the emperor. Following the first poem, the Emperor and Empress rose and walked out, followed by the court and the other guests.[32] Her next role at the Gymnase, as a foolish Russian princess, was entirely unsuited for her; her mother told her that her performance was "ridiculous".[31] She decided abruptly to quit the theater to travel, and like her mother, to take on lovers. She went briefly to Spain, then, at the suggestion of Alexandre Dumas, to Belgium.[33]

She carried to Brussels letters of introduction from Dumas, and was admitted to the highest levels of society. According to some later accounts, she attended a masked ball in Brussels where she met the Belgian aristocrat Henri, Hereditary Prince de Ligne, and had an affair with him.[34] Other accounts say that they met in Paris, where the Prince came often to attend the theater.[35] The affair was cut short when she learned that her mother had suffered a heart attack. She returned to Paris, where she found that her mother was better, but that she herself was pregnant from her affair with the Prince. She did not notify the Prince. Her mother did not want the fatherless child born under her roof, so she moved to a small apartment on rue Duphot, and on 22 December 1864, the 20-year-old actress gave birth to her only child, Maurice Bernhardt.[36]

Some accounts say that Prince Henri had not forgotten her. According to these versions, he learned her address from the theatre, arrived in Paris, and moved into the apartment with Bernhardt. After a month, he returned to Brussels and told his family that he wanted to marry the actress. The family of the Prince sent his uncle, General de Ligne, to break up the romance, threatening to disinherit him if he married Bernhardt.[37] According to other accounts, the Prince denied any responsibility for the child.[35] She later called the affair "her abiding wound", but she never discussed Maurice's parentage with anyone. When asked who his father was, she sometimes answered, "I could never make up my mind whether his father was Gambetta, Victor Hugo, or General Boulanger."[38] Many years later, in January 1885, when Bernhardt was famous, the Prince came to Paris and offered to formally recognise Maurice as his son, but Maurice politely declined, explaining he was entirely satisfied to be the son of Sarah Bernhardt.[39]

The Odéon (1866–1872)

To support herself after the birth of Maurice, Bernhardt played minor roles and understudies at the Port-Saint-Martin, a popular melodrama theatre. In early 1866, she obtained a reading with Felix Duquesnel, director of the Théâtre de L’Odéon (Odéon) on the Left Bank. Duquesnel described the reading years later, saying, "I had before me a creature who was marvelous gifted, intelligent to the point of genius, with enormous energy under an appearance frail and delicate, and a savage will." The co-director of the theatre for finance, Charles de Chilly, wanted to reject her as unreliable and too thin, but Duquesnel was enchanted; he hired her for the theater at a modest salary of 150 francs a month, which he paid out of his own pocket.[40] The Odéon was second in prestige only to the Comédie Française, and unlike that very traditional theatre, specialised in more modern productions. The Odéon was popular with the students of the Left Bank. Her first performances with the theatre were not successful. She was cast in highly stylised and frivolous 18th-century comedies, whereas her strong point on stage was her complete sincerity.[41] Her thin figure also made her look ridiculous in the ornate costumes. Dumas, her strongest supporter, commented after one performance, "she has the head of a virgin and the body of a broomstick."[42] Soon, however, with different plays and more experience, her performances improved; she was praised for her performance of Cordelia in King Lear.[citation needed] In June 1867, she played two roles in Athalie by Jean Racine; the part of a young woman and a young boy, Zacharie, the first of many male parts she played in her career. The influential critic Sarcey wrote "... she charmed her audience like a little Orpheus."[42]

Her breakthrough performance was in the 1868 revival of Kean by Alexandre Dumas, in which she played the female lead part of Anna Danby. The play was interrupted in the beginning by disturbances in the audience by young spectators who called out, "Down with Dumas! Give us Hugo!". Bernhardt addressed the audience directly: "Friends, you wish to defend the cause of justice. Are you doing it by making Monsieur Dumas responsible for the banishment of Monsieur Hugo?".[43] With this the audience laughed and applauded and fell silent. At the final curtain, she received an enormous ovation, and Dumas hurried backstage to congratulate her. When she exited the theatre, a crowd had gathered at the stage door and tossed flowers at her. Her salary was immediately raised to 250 francs a month.[44]

Her next success was her performance in François Coppée's Le Passant, which premiered at the Odéon on 14 January 1868,[45] playing the part of the boy troubadour, Zanetto, in a romantic renaissance tale.[46] Critic Theophile Gautier described the "delicate and tender charm" of her performance. It played for 150 performances, plus a command performance at the Tuileries Palace for Napoleon III and his court. Afterwards, the Emperor sent her a brooch with his initials written in diamonds.[47]

In her memoirs, she wrote of her time at the Odéon: "It was the theatre that I loved the most, and that I only left with regret. We all loved each other. Everyone was gay. The theatre was a like a continuation of school. All the young came there... I remember my few months at the Comédie Française. That little world was stiff, gossipy, jealous. I remember my few months at the Gymnase. There they talked only about dresses and hats, and chattered about a hundred things that had nothing to do with art. At the Odéon, I was happy. We thought only of putting on plays. We rehearsed mornings, afternoons, all the time. I adored that." Bernhardt lived with her longtime friend and assistant Madame Guerard and her son in a small cottage in the suburb of Auteuil, and drove herself to the theatre in a small carriage. She developed a close friendship with the writer George Sand, and performed in two plays that she authored.[48] She received celebrities in her dressing room, including Gustave Flaubert and Leon Gambetta. In 1869, as she became more prosperous, she moved to a larger seven-room apartment at 16 rue Auber in the center of Paris. Her mother began to visit her for the first time in years, and her grandmother, a strict Orthodox Jew, moved into the apartment to take care of Maurice. Bernhardt added a maid and a cook to her household, as well as the beginning of a collection of animals; she had one or two dogs with her at all times, and two turtles moved freely around the apartment.[49]

In 1868, a fire completely destroyed her apartment, along with all of her belongings. She had neglected to purchase insurance. The brooch presented to her by the Emperor and her pearls melted, as did the tiara presented by one of her lovers, Khalid Bey. She found the diamonds in the ashes, and the managers of the Odeon organised a benefit performance. The most famous soprano of the time, Adelina Patti, performed for free. In addition, the grandmother of her father donated 120,000 francs. Bernhardt was able to buy an even larger residence, with two salons and a large dining room, at 4 rue de Rome.[50]

Wartime service at the Odéon (1870–1871)

The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War abruptly interrupted her theatrical career. The news of the defeat of the French Army, the surrender of Napoleon III at Sedan, and the proclamation of the Third French Republic on 4 September 1870 was followed by a siege of the city by the Prussian Army. Paris was cut off from news and from its food supply, and the theatres were closed. Bernhardt took charge of converting the Odéon into a hospital for soldiers wounded in the battles outside the city.[51] She organised the placement of 32 beds in the lobby and the foyers, brought in her personal chef to prepare soup for the patients, and persuaded her wealthy friends and admirers to donate supplies for the hospital. Besides organising the hospital, she worked as a nurse, assisting the chief surgeon with amputations and operations.[52] When the coal supply of the city ran out, Bernhardt used old scenery, benches, and stage props for fuel to heat the theater.[53] In early January 1871, after 16 weeks of the siege, the Germans began to bombard the city with long-range cannons. The patients had to be moved to the cellar, and before long, the hospital was forced to close. Bernhardt arranged for serious cases to be transferred to another military hospital, and she rented an apartment on rue de Provence to house the remaining 20 patients. By the end of the siege, Bernhardt's hospital had cared for more than 150 wounded soldiers, including a young undergraduate from the École Polytechnique, Ferdinand Foch, who later commanded the Allied armies in the First World War.[54]

The French government signed an armistice on 19 January 1871, and Bernhardt learned that her son and family had been moved to Hamburg. She went to the new chief executive of the French Republic, Adolphe Thiers, and obtained a pass to go to Germany to return them. When she returned to Paris several weeks later, the city was under the rule of the Paris Commune. She moved again, taking her family to Saint-Germain-en-Laye. She later returned to her apartment on the rue de Rome in May, after the Commune was defeated by the French Army.

Ruy Blas and return to the Comédie française (1872–1878)

-

Bernhardt as the Queen of Spain in Ruy Blas (1872)

-

Phèdre by Racine at the Comédie française, (1873)

-

Bernhardt in her famous coffin, in which she sometimes slept or studied her roles (c. 1873)

-

Portrait by Georges Clairin (1876)

-

Bernhardt as Doña Sol in Hernani (1878)

The Tuileries Palace, city hall of Paris, and many other public buildings had been burned by the Commune or damaged in the fighting, but the Odéon was still intact. Charles-Marie Chilly, the co-director of the Odéon, came to her apartment, where Bernhardt received him reclining on a sofa. He announced that the theaters would reopen in October 1871, and he asked her to play the lead in a new play, Jean-Marie by André Theuriet. Bernhardt replied that she was finished with the theatre and was going to move to Brittany and start a farm. Chilly, who knew Bernhardt's moods well, told her that he understood and accepted her decision, and would give the role to Jane Essler, a rival actress. According to Chilly, Bernhardt immediately jumped up from the sofa and asked when the rehearsals would begin.[54]

Jean-Marie, about a young Breton woman forced by her father to marry an old man she did not love, was another critical and popular success for Bernhardt. The critic Sarcey wrote, "She has the sovereign grace, the penetrating charm, the I don't know what. She is a natural artist, an incomparable artist."[55] The directors of the Odéon next decided to stage Ruy Blas, a play written by Victor Hugo in 1838, with Bernhardt playing the role of the Queen of Spain. Hugo himself attended all the rehearsals. At first, Bernhardt pretended to be indifferent to him, but he gradually won her over and she became a fervent admirer. The play premiered on 16 January 1872. The opening night was attended by the Prince of Wales and by Hugo himself; after the performance, Hugo approached Bernhardt, dropped to one knee, and kissed her hand.[56]

Ruy Blas played to packed houses. A few months after it opened, Bernhardt received an invitation from Emile Perrin, Director of the Comédie Française, asking if she would return, and offering her 12,000 francs a year, compared with less than 10,000 at the Odéon.[57] Bernhardt asked Chilly if he would match the offer, but he refused. Always pressed by her growing expenses and growing household to earn more money, she announced her departure from the Odéon when she finished the run of Ruy Blas. Chilly responded with a lawsuit, and she was forced to pay 6,000 francs of damages. After the 100th performance of Ruy Blas, Hugo gave a dinner for Bernhardt and her friends, toasting "His adorable Queen and her Golden Voice."[56]

She formally returned to the Comédie Francaise on 1 October 1872, and quickly took on some of the most famous and demanding roles in French theatre. She played Junie in Britannicus by Jean Racine, the male role of Cherubin in The Marriage of Figaro by Pierre Beaumarchais, and the lead in Voltaire's five-act tragedy Zaïre.[58] In 1873, with just 74 hours to learn the lines and practice the part, she played the lead in Racine's Phédre, playing opposite the celebrated tragedian, Jean Mounet-Sully, who soon became her lover. The leading French critic Sarcey wrote, "This is nature itself served by marvelous intelligence, by a soul of fire, by the most melodious voice that ever enchanted human ears. This woman plays with her heart, with her entrails."[59] Phédre became her most famous classical role, performed over the years around the world, often for audiences who knew little or no French; she made them understand by her voice and gestures.[60]

In 1877, she had another success as Doña Sol in Hernani, a tragedy written 47 years earlier by Victor Hugo. Her lover in the play was her lover off-stage, as well, Mounet-Sully. Hugo himself was in the audience. The next day, he sent her a note: "Madame, you were great and charming; you moved me, me the old warrior, and, at a certain moment when the public, touched and enchanted by you, applauded, I wept. The tear which you caused me to shed is yours. I place it at your feet." The note was accompanied by a tear-shaped pearl on a gold bracelet.[61]

She maintained a highly theatrical lifestyle in her house on the rue de Rome. She kept a satin-lined coffin in her bedroom, and occasionally slept in it or lay in it to study her roles, though, contrary to the popular stories, she never took it with her on her travels. She cared for her younger sister who was ill with tuberculosis, and allowed her to sleep in her own bed, while she slept in the coffin. She posed in it for photographs, adding to the legends she created about herself.[62]

Bernhardt repaired her old relationships with the other members of the Comédie Française; she participated in a benefit for Madame Nathalie, the actress she had once slapped. However, she was frequently in conflict with Perrin, the director of the theatre. In 1878, during the Paris Universal Exposition, she took a flight over Paris with balloonist Pierre Giffard[citation needed] and painter Georges Clairin, in a balloon decorated with the name of her current character, Doña Sol. An unexpected storm carried the balloon far outside of Paris to a small town. When she returned by train to the city, Perrin was furious; he fined Bernhardt a thousand francs, citing a theatre rule which required actors to request permission before they left Paris. Bernhardt refused to pay, and threatened to resign from the Comédie. Perrin recognised that he could not afford to let her go. Perrin and the Minister of Fine Arts arranged a compromise; she withdrew her resignation, and in return was raised to a societaire, the highest rank of the theater.[63]

Triumph in London and departure from the Comédie Française (1879–1880)

Bernhardt was earning a substantial amount at the theatre, but her expenses were even greater. By this time she had eight servants, and she built her first house, an imposing mansion on rue Fortuny, not far from the Parc Monceau. She looked for additional ways to earn money. In June 1879, while the theatre of the Comédie Française in Paris was being remodeled, Perrin took the company on tour to London. Shortly before the tour began, a British theatre impresario named Edward Jarrett traveled to Paris and proposed that she give private performances in the homes of wealthy Londoners; the fee she would receive for each performance was greater than her monthly salary with the Comédie.[64] When Perrin read in the press about the private performances, he was furious. Furthermore, the Gaiety Theatre in London demanded that Bernhardt star in the opening performance, contrary to the traditions of Comédie Française, where roles were assigned by seniority, and the idea of stardom was scorned. When Perrin protested, saying that Bernhardt was only 10th or 11th in seniority, the Gaiety manager threatened to cancel the performance; Perrin had to give in. He scheduled Bernhardt to perform one act of Phèdre on the opening night, between two traditional French comedies, Le Misanthrope and Les Précieuses.[65]

On 4 June 1879, just before the opening curtain of her premiere in Phèdre, she suffered an attack of stage fright. She wrote later that she also pitched her voice too high, and was unable to lower it.[66] Nonetheless, the performance was a triumph. Though a majority of the audience could not understand Racine's classical French, she captivated them with her voice and gestures; one member of the audience, Sir George Arthur, wrote that "she set every nerve and fibre in their bodies throbbing and held them spellbound."[67] In addition to her performances of Zaire, Phèdre, Hernani, and other plays with her troupe, she gave the private recitals in the homes of British aristocrats arranged by Jarrett, who also arranged an exhibition of her sculptures and paintings in Piccadilly, which was attended by both the Prince of Wales and Prime Minister Gladstone. While in London, she added to her personal menagerie of animals. In London, she purchased three dogs, a parrot, and a monkey, and made a side trip to Liverpool, where she purchased a cheetah, a parrot, and a wolfhound and received a gift of six chameleons, which she kept in her rented house on Chester Square, and then took back to Paris.[68]

Back in Paris, she was increasingly discontented with Perrin and the management of the Comédie Française. He insisted that she perform the lead in a new play, L'Aventurière by Emile Augier, a play which she thought was mediocre. When she rehearsed the play without enthusiasm, and frequently forgot her lines, she was criticised by the playwright. She responded, "I know I'm bad, but not as bad as your lines." The play went ahead, but was a failure. She wrote immediately to Perrin, "You forced me to play when I was not ready... what I foresaw came to pass... this is my first failure at the Comédie and my last." She sent a resignation letter to Perrin, made copies, and sent them to the major newspapers. Perrin sued her for breach of contract; the court ordered her to pay 100,000 francs, plus interest, and she lost her accrued pension of 43,000 francs.[69] She did not settle the debt until 1900. Later, however, when the Comédie Française theatre was nearly destroyed by fire, she allowed her old troupe to use her own theatre.[70]

La Dame aux camélias and first American tour (1880–1881)

In April 1880, as soon as he learned Bernhardt had resigned from the Comédie Française, the impresario Edward Jarrett hurried to Paris and proposed that she make a theatrical tour of England and then the United States. She could select her repertoire and the cast. She would receive 5,000 francs per performance, plus 15% of any earnings over 15,000 francs, plus all of her expenses, plus an account in her name for 100,000 francs, the amount she owed to the Comédie Française. She accepted immediately.[71]

Now on her own, Bernhardt first assembled and tried out her new troupe at the Théâtre de la Gaîté-Lyrique in Paris. She performed for the first time La Dame aux Camélias, by Alexandre Dumas fils. She did not create the role; the play had first been performed by Eugénie Dochein in 1852, but it quickly became her most performed and most famous role. She played the role more than a thousand times, and acted regularly and successfully in it until the end of her life. Audiences were often in tears during her famous death scene at the end.[72]

She could not perform La Dame aux Camélias on a London stage because of British censorship laws; instead, she put on four of her proven successes, including Hernani and Phèdre, plus four new roles, including Adrienne Lecouvreur by Eugène Scribe and the drawing-room comedy Frou-frou by Meilhac-Halévy, both of which were highly successful on the London stage.[73] In six of the eight plays in her repertoire, she died dramatically in the final act. When she returned to Paris from London, the Comédie Française asked her to come back, but she refused their offer, explaining that she was making far more money on her own. Instead, she took her new company and new plays on tour to Brussels and Copenhagen, and then on a tour of French provincial cities.[74]

She and her troupe departed from Le Havre for America on 15 October 1880, arriving in New York on 27 October. On 8 November in New York City, she performed Scribe's Adrienne Lecouvreur at Booth's Theatre before an audience which had paid a top price of $40 for a ticket, an enormous sum at the time. Few in the audience understood French, but it was not necessary; her gestures and voice captivated the audience, and she received a thunderous ovation. She thanked the audience with her distinctive curtain call; she did not bow, but stood perfectly still, with her hands clasped under her chin, or with her palms on her cheeks, and then suddenly stretched them out to the audience. After her first performance in New York, she made 27 curtain calls. Although she was welcomed by theatre-goers, she was entirely ignored by New York high society, who considered her personal life scandalous.[75]

Bernhardt's first American tour carried her to 157 performances in 51 cities.[76] She travelled on a special train with her own luxurious palace car, which carried her two maids, two cooks, a waiter, her maitre d'hôtel, and her personal assistant, Madame Guérard. It also carried an actor named Édouard Angelo, whom she had selected to serve as her leading man, and, according to most accounts, her lover during the tour.[77][78] From New York, she made a side trip to Menlo Park, where she met Thomas Edison, who made a brief recording of her reciting a verse from Phèdre, which has not survived.[79] She crisscrossed the United States and Canada from Montreal and Toronto to Saint Louis and New Orleans, usually performing each evening, and departing immediately after the performance. She gave countless press interviews, and in Boston posed for photos on the back of a dead whale. She was condemned as immoral by the Bishop of Montreal and by the Methodist press, which only increased ticket sales.[79] She performed Phèdre six times and La Dame Aux Camélias 65 times (which Jarrett had renamed "Camille" to make it easier for Americans to pronounce, despite the fact that no character in the play has that name). On 3 May 1881, she gave her final performance of Camélias in New York. Throughout her life, she always insisted on being paid in cash. When Bernhardt returned to France, she brought with her a chest filled with $194,000 in gold coins.[80] She described the result of her trip to her friends: "I crossed the oceans, carrying my dream of art in myself, and the genius of my nation triumphed. I planted the French verb in the heart of a foreign literature, and it is that of which I am most proud."[81]

Return to Paris, European tour, Fédora to Theodora (1881–1886)

No crowd greeted Bernhardt when she returned to Paris on 5 May 1881, and theatre managers offered no new roles; the Paris press ignored her tour, and much of the Paris theatre world resented her leaving the most prestigious national theatre to earn a fortune abroad.[82] When no new plays or offers appeared, she went to London for a successful three-week run at the Gaiety Theater. This London tour included the first British performance of La Dame aux Camelias at the Shaftesbury Theatre; her friend, the Prince of Wales, persuaded Queen Victoria to authorise the performance.[83] Many years later, she gave a private performance of the play for the Queen while she was on holiday in Nice.[84] When she returned to Paris, Bernhardt contrived to make a surprise performance at the annual 14 July patriotic spectacle at the Paris Opera, which was attended by the President of France, and a houseful of dignitaries and celebrities. She recited the Marseillaise, dressed in a white robe with a tricolor banner, and at the end dramatically waved the French flag. The audience gave her a standing ovation, showered her with flowers, and demanded that she recite the song two more times.[85]

With her place in the French theatre world restored, Bernhardt negotiated a contract to perform at the Vaudeville Theatre in Paris for 1500 francs per performance, as well as 25 percent of the net profit. She also announced that she would not be available to begin until 1882. She departed on a tour of theatres in the French provinces, and then to Italy, Greece, Hungary, Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, Spain, Austria, and Russia. In Kiev and Odessa, she encountered anti-Semitic crowds who threw stones at her; pogroms were being conducted, forcing the Jewish population to leave.[86] However, in Moscow and St. Petersburg, she performed before Czar Alexander III, who broke court protocol and bowed to her. During her tour, she also gave performances for King Alfonso XII of Spain, and the Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. The only European country where she refused to play was Germany, due to the German annexation of French territory after the 1870–71 Franco-Prussian War.[87] Just before the tour began, she met Jacques Damala, who went with her as leading man and then, for eight months, became her first and only husband. ()

When she returned to Paris, she was offered a new role in Fédora, a melodrama written for her by Victorien Sardou. It opened on 12 December 1882, with her husband Damala as the male lead, and received good reviews. Critic Maurice Baring wrote, "a secret atmosphere emanated from her, an aroma, an attraction, which was at once exotic and cerebral ... She literally hypnotised her audience."[88] Another journalist wrote, "She is incomparable ... The extreme love, the extreme agony, the extreme suffering."[89] However, the abrupt end of her marriage shortly after the premiere put her back into financial distress. She had leased and refurbished a theatre, the Ambigu, specifically to give her husband leading roles, and made her 18-year-old son Maurice, who had no business experience, the manager. Fédora ran for just 50 performances and lost 400,000 francs. She was forced to give up the Ambigu, and then, in February 1883, to sell her jewellery, her carriages, and her horses at an auction.[90]

When Damala left, she took on a new leading man and lover, the poet and playwright Jean Richepin, who accompanied her on a quick tour of European cities to help pay off her debts.[91] She renewed her relationship with the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII.[92] When they returned to Paris, Bernhardt leased the theatre of Porte Saint-Martin and starred in a new play by Richepin, Nana-Sahib, a costume drama about love in British India in 1857. The play and Richepin's acting were poor, and it quickly closed.[93] Richepin then wrote an adaptation of Macbeth in French, with Bernhardt as Lady Macbeth, but it was also a failure. The only person who praised the play was Oscar Wilde, who was then living in Paris. He began writing a play, Salomé, in French, especially for Bernhardt, though it was quickly banned by British censors and she never performed it.[94]

Bernhardt then performed a new play by Sardou, Theodora (1884), a melodrama set in sixth-century Byzantium. Sardou wrote a nonhistoric but dramatic new death scene for Bernhardt; in his version, the empress was publicly strangled, whereas the historical empress died of cancer. Bernhardt travelled to Ravenna, Italy, to study and sketch the costumes seen in Byzantine mosaic murals, and had them reproduced for her own costumes. The play opened on 26 December 1884 and ran for 300 performances in Paris, and 100 in London, and was a financial success. She was able to pay off most of her debts, and bought a lion cub, which she named Justinian, for her home menagerie.[95] She also renewed her love affair with her former lead actor, Philippe Garnier.[96]

World tours (1886–1892)

Theodora was followed by two failures. In 1885, in homage to Victor Hugo, who had died a few months earlier, she staged one of his older plays, Marion Delorme, written in 1831, but the play was outdated and her role did not give her a chance to show her talents.[97] She next put on Hamlet, with her lover Philippe Garnier in the leading role and Bernhardt in the relatively minor role of Ophelia. The critics and audiences were not impressed, and the play was unsuccessful.[97] Bernhardt had built up large expenses, which included a 10,000 francs a month allowance paid to her son Maurice, a passionate gambler. Bernhardt was forced to sell her chalet in Saint-Addresse and her mansion on rue Fortuny, and part of her collection of animals. Her impresario, Edouard Jarrett, immediately proposed she make another world tour, this time to Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Peru, Panama, Cuba, and Mexico, then on to Texas, New York, England, Ireland, and Scotland. She was on tour for 15 months, from early 1886 until late 1887. On the eve of departure, she told a French reporter: "I passionately love this life of adventures. I detest knowing in advance what they are going to serve at my dinner, and I detest a hundred thousand times more knowing what will happen to me, for better or worse. I adore the unexpected."[95]

In every city she visited, she was feted and cheered by audiences. The actors Edouard Angelo and Philippe Garnier were her leading men. Emperor Pedro II of Brazil attended all of her performances in Rio de Janeiro, and presented her with a gold bracelet with diamonds, which was almost immediately stolen from her hotel. The two leading actors both fell ill with yellow fever, and her long-time manager, Edward Jarrett, died of a heart attack. Bernhardt was undaunted, however, and went crocodile hunting at Guayaquil, and also bought more animals for her menagerie. Her performances in every city were sold out, and by the end of the tour, she had earned more than a million francs. The tour allowed her to purchase her final home, which she filled with her paintings, plants, souvenirs, and animals.[98]

From then on, whenever she ran short of money (which generally happened every three or four years), she went on tour, performing both her classics and new plays. In 1888, she toured Italy, Egypt, Turkey, Sweden, Norway, and Russia. She returned to Paris in early 1889 with an enormous owl given to her by the Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, the brother of the Czar.[99] Her 1891–92 tour was her most extensive, including much of Europe, Russia, North and South America, Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and Samoa. Her personal luggage consisted of 45 costume crates for her 15 different productions, and 75 crates for her off-stage clothing, including her 250 pairs of shoes. She carried a trunk for her perfumes, cosmetics and makeup, and another for her sheets and tablecloths and her five pillows. After the tour, she brought back a trunk filled with 3,500,000 francs, but she also suffered a painful injury to her knee when she leaped off the parapet of the Castello Sant' Angelo in La Tosca. The mattress on which she was supposed to land was misplaced, and she landed on the boards.[100]

La Tosca to Cleopatra (1887–1893)

-

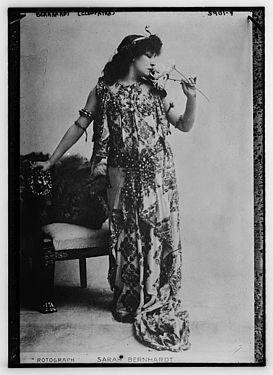

Bernhardt in La Tosca by Victorien Sardou (1887), photo by Nadar

-

Playing Joan of Arc in Jeanne d'Arc by Jules Barbier (1890)

-

Bernhardt in Cleopatra (1891)

-

Bernhardt in Cleopatra by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1896)

When Bernhardt returned from her 1886–87 tour, she received a new invitation to return to the Comédie Française. The theatre management was willing to forget the conflict of her two previous periods there, and offered a payment of 150,000 francs a year. The money appealed to her, and she began negotiations. However, the senior members of the company protested the high salary offered, and conservative defenders of the more traditional theatre also complained; one anti-Bernhardt critic, Albert Delpit of Le Gaulois, wrote, "Madame Sarah Bernhardt is forty-three; she can no longer be useful to the Comédie. Moreover, what roles could she have? I can only imagine that she could play mothers..." Bernhardt was deeply offended and immediately broke off negotiations.[101] She turned once again to Sardou, who had written a new play for her, La Tosca, which featured a prolonged and extremely dramatic death scene at the end. The play was staged at the Porte Saint-Martin Theatre, opening on 24 November 1887. It was extremely popular, and critically acclaimed. Bernhardt played the role for 29 consecutive sold-out performances. The success of the play allowed Bernhardt to buy a new pet lion for her household menagerie. She named him Scarpia, after the villain of La Tosca.[101] The play inspired Giacomo Puccini to write one of his most famous operas, Tosca (1900).[102]

Following this success, she acted in several revivals and classics, and many French writers offered her new plays. In 1887, she acted in a stage version of the controversial drama Thérèse Raquin by Emile Zola. Zola had previously been attacked due to the book's confronting content. Asked why she chose this play, she declared to reporters, "My true country is the free air, and my vocation is art without constraints."[99] The play was unsuccessful; it ran for just 38 performances.[103] She then performed another traditional melodrama, Francillon by Alexandre Dumas fils in 1888. A short drama she wrote herself, L'Aveu, disappointed both critics and the audience and lasted only 12 performances. She had considerably more success with Jeanne d'Arc by the poet Jules Barbier, in which the 45-year-old actress played Joan of Arc, a 19-year-old martyr.[104] Barbier had previously written the librettos for some of the most famous French operas of the period, including Faust by Charles Gounod and The Tales of Hoffmann by Jacques Offenbach. Her next success was another melodrama by Sardou and Moreau, Cleopatra, which allowed her to wear elaborate costumes and finished with a memorable death scene. For this scene, she kept two live garter snakes, which played the role of the poisonous asp which bites Cleopatra. For realism, she painted the palms of her hands red, though they could hardly be seen from the audience. "I shall see them," she explained. "If I catch sight of my hand, it will be the hand of Cleopatra."[105]

Bernhardt's violent portrayal of Cleopatra led to the theatrical story of a matron in the audience exclaiming to her companion "How unlike, how very unlike, the home life of our own dear Queen!"[106]

Théâtre de la Renaissance (1893–1899)

-

Bernhardt in Gismonda by Victorien Sardou (1894)

-

Poster for Gismonda by Alphonse Mucha (1894)

-

As Melissande in La Princesse Lointaine by Edmond Rostand (1897)

-

Bernhardt in Cleopatra by Sardou (1899)

Bernhardt made a two-year world tour (1891–1893) to replenish her finances. Upon returning to Paris, she paid 700,000 francs for the Théâtre de la Renaissance, and from 1893 until 1899, was its artistic director and lead actress. She managed every aspect of the theatre, from the finances to the lighting, sets, and costumes, as well as appearing in eight performances a week.[107] She imposed a rule that women in the audience, no matter how wealthy or famous, had to take off their hats during performances, so the rest of the audience could see, and eliminated the prompter's box from the stage, declaring that actors should know their lines. She abolished in her theatre the common practice of hiring claqueurs in the audience to applaud stars.[108] She used the new technology of lithography to produce vivid color posters, and in 1894, she hired Czech artist Alphonse Mucha to design the first of a series of posters for her play Gismonda. He continued to make posters of her for six years.[109]

In five years, Bernhardt produced nine plays, three of which were financially successful. The first was a revival of her performance as Phédre, which she took on tour around the world. In 1898, she had another success, in the play Lorenzaccio, playing the male lead role in a Renaissance revenge drama written in 1834 by Alfred de Musset, but never before actually staged. As her biographer Cornelia Otis Skinner wrote, she did not try to be overly masculine when she performed male roles: "Her male impersonations had the sexless grace of the voices of choirboys, or the not quite real pathos of Pierrot."[110] Anatole France wrote of her performance in Lorenzaccio: "She formed out of her own self a young man melancholic, full of poetry and of truth."[111] This was followed by another successful melodrama by Sardou, Gismonda, one of Bernhardt's few plays not finishing with a dramatic death scene. Her co-star was Lucien Guitry, who also acted as her leading man until the end of her career. Besides Guitry, she shared the stage with Édouard de Max, her leading man in 20 productions, and Constant Coquelin, who frequently toured with her.[112]

In April 1895, she played the lead role in a romantic and poetic fantasy, Princess Lointaine, by little-known 27-year-old poet Edmond Rostand. It was not a monetary success and lost 200,000 francs, but it began a long theatrical relationship between Bernhardt and Rostand. Rostand went on to write Cyrano de Bergerac and became one of the most popular French playwrights of the period.[113]

In 1898, she performed the female lead in the controversial play La Ville Morte by the Italian poet and playwright Gabriele D'Annunzio; the play was fiercely attacked by critics because of its theme of incest between brother and sister. Along with Emile Zola and Victorien Sardou, Bernhardt also became an outspoken defender of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish army officer falsely accused of betraying France. The issue divided Parisian society; a conservative newspaper ran the headline, "Sarah Bernhardt has joined the Jews against the Army", and Bernhardt's own son Maurice condemned Dreyfus; he refused to speak to her for a year.[114]

At the Théâtre de la Renaissance, Bernhardt staged and performed in several modern plays, but she was not a follower of the more natural school of acting that was coming into fashion at the end of the 19th century, preferring a more dramatic expression of emotions. "In the theatre," she declared, "the natural is good, but the sublime is even better."[115]

Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt (1899–1900)

-

The Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt (now the Théâtre de la Ville)

(c. 1905) -

Bernhardt in Hamlet (1899)

-

Poster by Mucha for Hamlet (1899)

-

Bernhardt in L'Aiglon (1900)

Despite her successes, her debts continued to mount, reaching two million gold francs by the end of 1898. Bernhardt was forced to give up the Renaissance, and was preparing to go on another world tour when she learned that a much larger Paris theater, the Théâtre des Nations on Place du Châtelet, was for lease. The theatre had 1,700 seats, twice the size of the Renaissance, enabling her to pay off the cost of performances more quickly; it had an enormous stage and backstage, allowing her to present several different plays a week; and since it was originally designed as a concert hall, it had excellent acoustics. On 1 January 1899, she signed a 25-year lease with the City of Paris, though she was already 55 years old.[116]

She renamed it the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt, and began to renovate it to suit her needs. The façade was lit by 5,700 electric bulbs, 17 arc lights, and 11 projectors.[117] She completely redecorated the interior, replacing the red plush and gilt with yellow velvet, brocade, and white woodwork. The lobby was decorated with life-sized portraits of her in her most famous roles, painted by Mucha, Louise Abbéma, and Georges Clairin. Her dressing room was a five-room suite, which, after the success of her Napoleonic play L'Aiglon, was decorated in Empire Style, featuring a marble fireplace with a fire Bernhardt kept burning year round, a huge bathtub that was filled with the flowers she received after each performance, and a dining room fitting 12 people, where she entertained guests after the final curtain.[118]

Bernhardt opened the theatre on 21 January 1899 with a revival of Sardou's La Tosca, which she had first performed in 1887. This was followed by revivals of her other major successes, including Phédre, Theodora, Gismonda, and La Dame aux Camélias, plus Octave Feuillet's Dalila, Gaston de Wailly's Patron Bénic, and Rostand's La Samaritaine, a poetic retelling of the story of the Samaritan woman at the well from the Gospel of St. John. On 20 May, she premiered one of her most famous roles, playing the titular character of Hamlet in a prose adaptation which she had commissioned from Eugène Morand and Marcel Schwob.[119] She played Hamlet in a manner which was direct, natural, and very feminine.[120] Her performance received largely positive reviews in Paris, but mixed reviews in London. The British critic Max Beerbohm wrote, "the only compliment one can conscientiously pay her is that her Hamlet was, from first to last, a truly grand dame."[121]

In 1900, Bernhardt presented L'Aiglon, a new play by Rostand. She played the Duc de Reichstadt, the son of Napoleon Bonaparte, imprisoned by his unloving mother and family until his melancholy death in the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna. L'Aiglon was a verse drama, six acts long. The 56-year-old actress studied the walk and posture of young cavalry officers and had her hair cut short to impersonate the young Duke. The Duke's stage mother, Marie-Louise of Austria, was played by Maria Legault, an actress 14 years younger than Bernhardt. The play ended with a memorable death scene; according to one critic, she died "as dying angels would die if they were allowed to."[122] The play was extremely successful; it was especially popular with visitors to the 1900 Paris International Exposition, and ran for nearly a year, with standing-room places selling for as much as 600 gold francs. The play inspired the creation of Bernhardt souvenirs, including statuettes, medallions, fans, perfumes, postcards of her in the role, uniforms and cardboard swords for children, and pastries and cakes; the famed chef Escoffier added Peach Aiglon with Chantilly cream to his repertoire of desserts.[123]

Bernhardt continued to employ Mucha to design her posters, and expanded his work to include theatrical sets, programs, costumes, and jewellery props. His posters became icons of the Art Nouveau style. To earn more money, Bernhardt set aside a certain number of printed posters of each play to sell to collectors.[109][124]

Farewell tours (1901–1913)

-

Bernhardt as Zoraya in La Sorcière by Sardou (1903)

-

Playing Pelléas in Pelléas and Mélisande (1905)

-

Bernhardt in the role of Phedre at the Hearst Greek Theatre at the University of California, Berkeley (1906)

-

Portrait of Sarah Bernhardt in 1910 by Henry Walter Barnett

After her season in Paris, Bernhardt performed L'Aiglon in London, and then made her sixth tour to the United States. On this tour, she travelled with Constant Coquelin, then the most popular leading man in France. Bernhardt played the secondary role of Roxanne to his Cyrano de Bergerac, a role which he had premiered, and he co-starred with her as Flambeau in L'Aiglon and as the first grave-digger in Hamlet.[125]

She also changed, for the first time, her resolution not to perform in Germany or the "occupied territories" of Alsace and Lorraine. In 1902, at the invitation of the French ministry of culture, she took part in the first cultural exchange between Germany and France since the 1870 war. She performed L'Aiglon 14 times in Germany; Kaiser William II of Germany attended two performances and hosted a dinner in her honour in Potsdam.[126]

During her German tour, she began to suffer agonising pain in her right knee, probably connected with a fall she had suffered on stage during her tour in South America. She was forced to reduce her movements in L'Aiglon. A German doctor recommended that she halt the tour immediately and have surgery, followed by six months of complete immobilisation of her leg. Bernhardt promised to see a doctor when she returned to Paris, but continued the tour.[127]

In 1903, she had another unsuccessful role playing another masculine character in the opera Werther, a gloomy adaptation of the story by German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. However, she quickly came back with another hit, La Sorcière by Sardou. She played a Moorish sorceress in love with a Christian Spaniard, leading to her persecution by the church. This story of tolerance, coming soon after the Dreyfus affair, was financially successful, with Bernhardt often giving both a matinee and evening performance.[127]

Between 1904 and 1906, she appeared in a wide range of parts, including in Francesca di Rimini by Francis Marion Crawford, the role of Fanny in Sapho by Alphonse Daudet, the magician Circe in a play by Charles Richet, the part of Marie Antoinette in the historic drama Varennes by Lavedan and Lenôtre, the part of the prince-poet Landry in a version of Sleeping Beauty by Richepin and Henri Cain, and a new version of the play Pelléas and Mélisande by symbolist poet Maurice Maeterlinck, in which she played the male role of Pelléas with the British actress Mrs Patrick Campbell as Melissande.[128] She also starred in a new version of Adrienne Lecouvreur, which she wrote herself, different from the earlier version which had been written for her by Scribe. During this time, she wrote a drama, Un Coeur d'Homme, in which she had no part, which was performed at the Théâtre des Arts, but lasted only three performances.[129] She also taught acting briefly at the Conservatory, but found the system there too rigid and traditional. Instead, she took aspiring actresses and actors into her company, trained them, and used them as unpaid extras and bit players.[130]

Bernhardt made her first American Farewell Tour in 1905–1906, the first of four farewell tours she made to the US, Canada, and Latin America, with her new managers, the Shubert brothers. She attracted controversy and press attention when, during her 1905 visit to Montreal, the Roman Catholic bishop encouraged his followers to throw eggs at Bernhardt, because she portrayed prostitutes as sympathetic characters. The US portion of the tour was complicated due to the Shuberts' competition with the powerful syndicate of theatre owners which controlled nearly all the major theatres and opera houses in the United States. The syndicate did not allow outside producers to use their stages. As a result, in Texas and Kansas City, Bernhardt and her company performed under an enormous circus tent, seating 4,500 spectators, and in skating rinks in Atlanta, Savannah, Tampa, and other cities. Her private train took her to Knoxville, Dallas, Denver, Tampa, Chattanooga, and Salt Lake City, then on to the West Coast. She could not play in San Francisco because of the recent 1906 San Francisco earthquake, but she performed across the bay in the Hearst Greek Theatre at the University of California at Berkeley, and gave a recital, titled A Christmas Night during the Terror, for inmates at San Quentin penitentiary.[131]

Her tour continued into South America, where it was marred by a more serious event: at the conclusion of La Tosca in Rio de Janeiro, she leaped, as always, from the wall of the fortress to plunge to her death in the Tiber. This time, however, the mattress on which she was supposed to land had been positioned incorrectly. She landed on her right knee, which had already been damaged in earlier tours. She fainted and was taken from the theatre on a stretcher, but refused to be treated in a local hospital. She later sailed by ship from Rio to New York. When she arrived, her leg had swollen, and she was immobilised in her hotel for 15 days before returning to France.[132]

In 1906–1907, the French government finally awarded Bernhardt the Legion d'Honneur, but only in her role as a theatre director, not as an actress. However, the award at that time required a review of the recipients' moral standards, and Bernhardt's behavior was still considered scandalous. Bernhardt ignored the snub and continued to play both inoffensive and controversial characters. In November 1906, she starred in La Vierge d'Avila, ou La Courtisan de Dieu, by Catulle Mendes, playing Saint Theresa, followed on 27 January 1907 by Les Bouffons, by Miguel Zamocois, in which she played a young and amorous medieval lord.[133] In 1909, she again played the 19-year-old Joan of Arc in Le Procès de Jeanne d'Arc by Émile Moreau. French newspapers encouraged schoolchildren to view her personification of French patriotism.[134]

Despite the injury to her leg, she continued to go on tour every summer, when her own theatre in Paris was closed. In June 1908, she made a 20-day tour of Britain and Ireland, performing in 16 different cities.[135] In 1908–1909, she toured Russia and Poland. Her second American farewell tour (her eighth tour in America) began in late 1910. She took along a new leading man, the Dutch-born Lou Tellegen, a very handsome actor who had served as a model for the sculpture Eternal Springtime by Auguste Rodin, and who became her co-star for the next two years, as well as her escort to all events, functions, and parties. He was not a particularly good actor, and had a strong Dutch accent, but he was successful in roles such as Hippolyte in Phedre, where he could take off his shirt and show off his physique. In New York, she created yet another scandal when she appeared in the role of Judas Iscariot in Judas by the American playwright John Wesley De Kay. It was performed in New York's Globe Theater for only one night in December 1910 before it was banned by local authorities. It was also banned in Boston and Philadelphia.[136] The tour took her from Boston to Jacksonville, through Mississippi, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania, to Canada and Minnesota, usually one new city and one performance every day.[137]

In April 1912, Bernhardt presented a new production in her theatre, Les Amours de la reine Élisabeth, a romantic costume drama by Émile Moreau about Queen Elizabeth's romances with Robert Dudley and Robert Devereux. It was lavish and expensive, but was a monetary failure, lasting only 12 performances. Fortunately for Bernhardt, she was able to pay off her debt with the money she received from the American producer Adolph Zukor for a film version of the play.[138] ()

She departed on her third farewell tour of the United States in 1913–1914, when she was 69. Her leg had not yet fully healed, and she was unable to perform an entire play, only selected acts. She also separated from her co-star and lover of the time, Lou Tellegen. When the tour ended, he remained in the United States, where he briefly became a silent movie star, while she returned to France in May 1913.[139]

Amputation of leg and wartime performances (1914–1918)

In December 1913, Bernhardt performed another success with the drama Jeanne Doré. On 16 March, she was made a Chevalier of the Legion d'Honneur. Despite her successes, she was still short of money. She had made her son Maurice the director of her new theatre, and permitted him to use the receipts of the theatre to pay his gambling debts, eventually forcing her to pawn some of her jewels to pay her bills.[140]

In 1914, she went as usual to her holiday home on Belle-Île with her family and close friends. There, she received the news of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and the beginning of the First World War. She hurried back to Paris, which was threatened by an approaching German army. In September, Bernhardt was asked by the Minister of War to move to a safer place. She departed for a villa on the Bay of Arcachon, where her physician discovered that gangrene had developed on her injured leg. She was transported to Bordeaux, where on 22 February 1915, a surgeon amputated her leg almost to the hip. She refused the idea of an artificial leg, crutches, or a wheelchair, and instead was usually carried in a palanquin she designed, supported by two long shafts and carried by two men. She had the chair decorated in the Louis XV style, with white sides and gilded trim.[141]

She returned to Paris on 15 October, and, despite the loss of her leg, continued to go on stage at her theatre; scenes were arranged so she could be seated, or supported by a prop with her leg hidden. She took part in a patriotic "scenic poem" by Eugène Morand, Les Cathédrales, playing the part of Strasbourg Cathedral; first, while seated, she recited a poem; then she hoisted herself up on her one leg, leaned against the arm of the chair, and declared "Weep, weep, Germany! The German eagle has fallen into the Rhine!"[142]

Bernhardt joined a troupe of famous French actors and traveled to the Battle of Verdun and the Battle of the Argonne, where she performed for soldiers who were just returned or about to go into battle. Propped on pillows in an armchair, she recited her patriotic speech at Strasbourg Cathedral. Another actress present at the event, Beatrix Dussanne, described her performance: "The miracle again took place; Sarah, old, mutilated, once more illuminated a crowd by the rays of her genius. This fragile creature, ill, wounded and an immobile, could still, through the magic of the spoken word, re-instill heroism in those soldiers weary from battle."[143]

She returned to Paris in 1916 and made two short films on patriotic themes, one based on the story of Joan of Arc, the other called Mothers of France. Then she embarked on her final American farewell tour. Despite the threat of German submarines, she crossed the Atlantic and toured the United States, performing in major cities including New York and San Francisco. Bernhardt was diagnosed with uremia, and had to have an emergency kidney operation. She recuperated in Long Beach, California, for several months, writing short stories and novellas for publication in French magazines. In 1918, she returned to New York and boarded a ship to France, landing in Bordeaux on 11 November 1918, the day that the armistice was signed ending the First World War.[144]

Final years (1919–1923)

In 1920, she resumed acting in her theatre, usually performing single acts of classics such as Racine's Athelee, which did not require much movement. For her curtain calls, she stood, balancing on one leg and gesturing with one arm. She also starred in a new play, Daniel, written by her grandson-in-law, playwright Louis Verneuil. She played the male lead role, but appeared in just two acts. She took the play and other famous scenes from her repertory on a European tour and then for her last tour of England, where she gave a special command performance for Queen Mary, followed by a tour of the British provinces.[145]

In 1921, Bernhardt made her last tour of the French provinces, lecturing about theatre and reciting the poetry of Rostand. Later that year, she produced a new play by Rostand, La Gloire, and another play by Verneuil, Régine Arnaud in 1922. She continued to entertain guests at her home. One such guest, French author Colette, described being served coffee by Bernhardt: "The delicate and withered hand offering the brimming cup, the flowery azure of the eyes, so young still in their network of fine lines, the questioning and mocking coquetry of the tilted head, and that indescribable desire to charm, to charm still, to charm right up to the gates of death itself."[146]

In 1922, she began rehearsing a new play by Sacha Guitry, called Un Sujet de Roman. On the night of the dress rehearsal, she collapsed, going into a coma for an hour, then awakened with the words, "when do I go on?" She recuperated for several months, with her condition improving; she began preparing for a new role as Cleopatra in Rodogune by Corneille, and agreed to make a new film by Sasha Guitry called La Voyante, for a payment of 10,000 francs a day. She was too weak to travel, so a room in her house on Boulevard Pereire was set up as a film studio, with scenery, lights, and cameras. However, on 21 March 1923, she collapsed again, and never recovered. She died from uremia on the evening of 26 March 1923. Newspaper reports stated she died "peacefully, without suffering, in the arms of her son".[147] At her request, her Funeral Mass was celebrated at the church of Saint-François-de-Sales, which she attended when she was in Paris.[148] The following day, 30,000 people attended her funeral to pay their respects, and an enormous crowd followed her casket from the Church of Saint-Francoise-de-Sales to Pere Lachaise Cemetery, pausing for a moment of silence outside her theatre.[149] The inscription on her tombstone is the name "Bernhardt".[150]

Motion pictures

-

Bernhardt in the film Camille (La Dame aux camélias) with André Calmettes (1911)

-

As Queen Elizabeth in the film Les Amours de la reine Élisabeth (The Loves of Queen Elizabeth) with Lou Tellegen (1912)

Bernhardt was one of the first actresses to star in moving pictures. The first projected film was shown by the Lumiere brothers at the Grand Café in Paris on 28 December 1895. In 1900, the cameraman who had shot the first films for the Lumiere brothers, Clément Maurice, approached Bernhardt and asked her to make a film out of a scene from her stage production of Hamlet. The scene was Prince Hamlet's duel with Laertes, with Bernhardt in the role of Hamlet. Maurice made a phonograph recording at the same time, so the film could be accompanied by sound. The sound of the clashing wooden prop swords was not loud and realistic enough, so Maurice had a stage hand bang pieces of metal together in sync with the sword fight. Maurice's finished two-minute film, Le Duel d'Hamlet, was presented to the public at the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition between 14 April and 12 November 1900 in Paul Decauville's program, Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre. This program contained short films of many other famous French theatre stars of the day.[151] The sound quality on the disks and the synchronization were very poor, so the system never became a commercial success. Nonetheless, her film is cited as one of the first examples of a sound film.[152]

Eight years later, in 1908, Bernhardt made a second motion picture, La Tosca. This was produced by Le Film d’Art and directed by André Calmettes from the play by Victorien Sardou. The film has been lost. Her next film, with her co-star and lover Lou Tellegen, was La Dame aux Camelias, called "Camille". When she performed on this film, Bernhardt changed both the fashion in which she performed, significantly accelerating the speed of her gestural action.[153] The film was a success in the United States, and in France, the young French artist and later screenwriter Jean Cocteau wrote, "What actress can play a lover better than she does in this film? No one!"[154] Bernhardt received $30,000 for her performance.

Shortly afterwards, she made another film of a scene from her play Adrienne Lecouvreur with Tellegen, in the role of Maurice de Saxe. Then, in 1912, the pioneer American producer Adolph Zukor came to London and filmed her performing scenes from her stage play Queen Elizabeth with her lover Tellegen, with Bernhardt in the role of Lord Essex.[155] To make the film more appealing, Zukor had the film print hand-tinted, making it one of the first color films. The Loves of Queen Elizabeth premiered at the Lyceum Theater in New York City on 12 July 1912, and was a financial success; Zukor invested $18,000 in the film and earned $80,000, enabling him to found the Famous Players Film Company, which later became Paramount Pictures.[156] The use of the visual arts–specifically famous c.19 painting–to frame scenes and elaborate narrative action is significant in the work.[153]

Bernhardt was also the subject and star of two documentaries, including Sarah Bernhardt à Belle-Isle (1915), a film about her daily life at home. This was one of the earliest films by a celebrity inviting us into the home, and is again significant for the use it makes of contemporary art references in the mis-en-scene of the film.[153] She also made Jeanne Doré in 1916. This was produced by Eclipse and directed by Louis Mercanton and René Hervil from the play by Tristan Bernard. In 1917 she made a film called Mothers of France (Mères Françaises). Produced by Eclipse it was directed by Louis Mercanton and René Hervil with a screenplay by Jean Richepin. As Victoria Duckett explains in her book Seeing Sarah Bernhardt: Performance and Silent Film, this film was a propaganda film shot on the front line with the intent to urge America to join the War.[153]

In the weeks before her death in 1923, she was preparing to make another motion picture from her own home, La Voyante, directed by Sacha Guitry. She told journalists, "They're paying me ten thousand francs a day, and plan to film for seven days. Make the calculation. These are American rates, and I don't have to cross the Atlantic! At those rates, I'm ready to appear in any films they make."[157] However, she died just before the filming began.[158]

Painting and sculpture

Fondation Bemberg Toulouse

Bernhardt began painting while she was at the Comédie-Française; since she rarely performed more than twice a week, she wanted a new activity to fill her time. Her paintings were mostly landscapes and seascapes, with many painted at Belle-Île. Her painting teachers were close and lifelong friends Georges Clairin and Louise Abbéma. She exhibited a 2-m-tall canvas, The Young Woman and Death, at the 1878 Paris Salon.[159]

Her passion for sculpture was more serious. Her sculpture teacher was Mathieu-Meusnier, an academic sculptor who specialised in public monuments and sentimental storytelling pieces.[160] She quickly picked up the techniques; she exhibited and sold a high-relief plaque of the death of Ophelia and, for the architect Charles Garnier, she created the allegorical figure of Song for the group Music on the façade of the Opera House of Monte Carlo.[161] She also exhibited a group of figures, called Après la Tempête (After the Storm), at the 1876 Paris Salon, receiving an honourable mention. Bernhardt sold the original work, the molds, and signed plaster miniatures, earning more than 10,000 francs.[161] The original is now displayed the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. Fifty works by Bernhardt have been documented, of which 25 are known to still exist.[162] Several of her works were also shown in the 1893 Columbia Exposition in Chicago and at the 1900 Exposition Universelle.[163] While on tour in New York, she hosted a private viewing of her paintings and sculptures for 500 guests.[164] In 1880, she made an Art Nouveau decorative bronze inkwell, a self-portrait with bat wings and a fish tail,[165] possibly inspired by her 1874 performance in Le Sphinx.[166] She set up a studio at 11 boulevard de Clichy in Montmartre, where she frequently entertained her guests dressed in her sculptor's outfit, including white satin blouse and white silk trousers. Rodin dismissed her sculptures as "old-fashioned tripe", and she was attacked in the press for pursuing an activity inappropriate for an actress. She was defended by Emile Zola, who wrote, "How droll! Not content with finding her thin, or declaring her mad, they want to regulate her daily activities, ... Let a law be passed immediately to prevent the accumulation of talent!"[167]

The Art of the Theatre

In her final years, Bernhardt wrote a textbook on the art of acting. She wrote whenever she had time, usually between productions, and when she was on vacation at Belle-Île. After her death, the writer Marcel Berger, her close friend, found the unfinished manuscript among her belongings in her house on boulevard Pereire. He edited the book, and it was published as L'Art du Théâtre in 1923. An English translation was published in 1925.[168]

She paid particular attention to the use of the voice, "the instrument the most necessary to the dramatic artist." It was the element, she wrote, which connected the artist with the audience. "The voice must have all the harmonies, ... serious, plaintive, vibrant and metallic." For a voice to be fully complete, she wrote, "It is necessary that it be very slightly nasal. An artist who has a dry voice can never touch the public." She also stressed the importance for artists to train their breathing for long passages. She suggested that an actress should be able to recite the following passage from Phédre in a single breath:

- Hélas! ils se voyaient avec pleine licence,

- Le ciel de leurs soupirs approuvait l'innocence;

- Ils suivaient sans remords leur penchant amoureux;

- Tous les jours se levaient clairs et sereins pour eux! [169]

She noted that "the art of our art is not to have it noticed by the public... We must create an atmosphere by our sincerity, so that public, gasping, distracted, should not regain its equilibrium and free will until the fall of the curtain. That which is called the work, in our art, should only be the search for the truth."[170]

She also insisted that artists should express their emotions clearly without words, using "their eye, their hand, the position of the chest, the tilting of the head... The exterior form of the art is often the entire art; at least, it is that which strikes the audience the most effectively." She encouraged actors to "Work, overexcite your emotional expression, become accustomed to varying your psychological states and translating them... The diction, the way of standing, the look, the gesture are predominant in the development of the career of an artist."[171]

She explained why she liked to perform male roles: "The roles of men are in general more intellectual than the roles of women... Only the role of Phédre gives me the charm of digging into a heart that is truly anguished... Always, in the theatre, the parts played by the men are the best parts. And yet theatre is the sole art where women can sometimes be superior to men."[172]

Memory and improvisation

Bernhardt had a remarkable ability to memorise a role quickly. She recounted in L'Art du Théâtre that "I only have to read a role two or three times and I know it completely; but the day that I stop playing the piece the role escapes me entirely... My memory can't contain several parts at the same time, and it's impossible for me to recite off-hand a tirade from Phèdre or Hamlet. And yet I can remember the smallest events from my childhood."[173] She also suffered, particularly early in her career, bouts of memory loss and stage fright. Once, she was seriously ill before a performance of L'Etrangère at the Gaiety Theatre in London, and the doctor gave her a dose of painkiller, either opium or morphine. During the performance, she went on stage, but could not remember what she was supposed to say. She turned to another actress, and announced, "If I made you come here, Madame, it is because I wanted to instruct you in what I want done... I have thought about it, and I do not want to tell you today", then walked offstage. The other actors, astonished, quickly improvised an ending to the scene. After a brief rest, her memory came back, and Bernhardt went back on stage, and completed the play.[173]

During another performance on her world tour, a backstage door was opened during a performance of Phèdre, and a cold wind blew across the stage as Bernhardt was reciting. Without interrupting her speech, she added "If someone doesn't close that door I will catch pneumonia." The door was closed, and no one in the audience seemed to notice the addition.[173]

Critical appraisals

French drama critics praised Bernhardt's performances; Francisque Sarcey, an influential Paris critic, wrote of her 1871 performance in Marie, "She has a sovereign grace, a penetrating charm, and I don't know what. She is a natural and an incomparable artist."[55] Reviewing her performance of Ruy Blas in 1872, the critic Théodore de Banville wrote that Bernhardt "declaimed like a bluebird sings, like the wind sighs, like the water murmurs."[174] Of the same performance, Sarcey wrote: "She added the music of her voice to the music of the verse. She sang, yes, sang with her melodious voice..."[174]