Men Against Fire

| "Men Against Fire" | |

|---|---|

| Black Mirror episode | |

Malachi Kirby as Stripe, whose acting was well-received. The episode is set in a war in an unspecified location, perhaps in Eastern Europe.[1] | |

| Episode no. | Series 3 Episode 5 |

| Directed by | Jakob Verbruggen |

| Written by | Charlie Brooker |

| Original release date | 21 October 2016 |

| Running time | 60 minutes |

| Guest appearances | |

| |

"Men Against Fire" is the fifth and penultimate episode of the third series of British science fiction anthology series Black Mirror. Written by series creator and showrunner Charlie Brooker and directed by Jakob Verbruggen, it premiered on Netflix on 21 October 2016, together with the rest of series three.

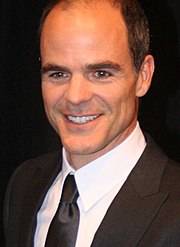

The episode follows Stripe (Malachi Kirby), a soldier who hunts humanoid mutants known as roaches. After a malfunctioning of his MASS, a neural implant, he discovers that these "roaches" are ordinary human beings. In a fateful confrontation with the psychologist Arquette (Michael Kelly), Stripe learns that the MASS alters his perception of reality. The episode was first conceived under the name "Inbound" in 2010. Its storyline shifted over time, influenced by Brooker reading Men Against Fire by S.L.A. Marshall and On Killing by Dave Grossman.

The episode received mixed critical reception. Positive reviews praised Kirby and Kelly's acting as well as the relevance of the episode in a time of rising xenophobia in Europe and America. Other critics found the plot twist predictable and remarked that the storyline relied too heavily on cliches. Critical commentary frequently notes parallels to Nazi Germany. "Men Against Fire" was ranked poorly against other Black Mirror episodes by reviewers.

Plot

"Stripe" Koinange (Malachi Kirby) and "Hunter" Raiman (Madeline Brewer) are squadmates in a military that hunts roaches—pale, snarling, humanoid monsters with sharp teeth. Each soldier has a neural implant called MASS that provides data via augmented reality. Stripe and Hunter's squad searches a farmhouse while squad leader Medina (Sarah Snook) interrogates the owner, a devout Christian (Francis Magee). Stripe discovers a nest of roaches, one of whom points an LED device at Stripe; unfazed, he shoots one roach dead and stabs another to death. Medina arrests the owner and the squad burns down the farmhouse.

Stripe is rewarded with an erotic dream following his kills, but his MASS glitches during it. After further malfunctions the following day, Stripe has his MASS tested and consults a psychologist, Arquette (Michael Kelly), but neither visit reveals any problems.

The next day, Medina, Stripe and Hunter arrive at an abandoned housing complex. After a roach-sniper suddenly kills Medina, the other two soldiers enter the building as the sniper shoots at them. Stripe encounters a woman and urges her to flee, but Hunter shoots her dead. Stripe finds another woman (Ariane Labed) with her child, and Hunter prepares to shoot them. Stripe intervenes and wrestles Hunter, knocking her unconscious as she shoots him in the stomach. Stripe gets up and escapes with the mother and son.

They reach a cave in the woods where the woman, named Catarina, explains that the MASS implant alters soldiers' senses to show people of her ethnic group as inhuman "roaches". They are victims of a genocide justified by the military as genetic cleansing. While laypeople see the group as they are, they treat them as inferior due to propaganda. Hunter arrives and kills Catarina and her son Alec, then knocks Stripe unconscious.

Stripe awakens in a cell, where Arquette apologises for his MASS glitch, caused by the LED device. Arquette reveals that MASS alters soldiers' senses so they can kill without hesitation or remorse, and that Stripe consented to this when he enlisted before having his memory wiped. Stripe has the choice to allow his MASS and memory to be reset, or to be imprisoned. Arquette forces Stripe to rewatch the sensory feed of his farmhouse raid, where he now sees himself gruesomely killing people.

In the final scene, Stripe, now a decorated officer, approaches the house from his erotic dreams. He has tears streaming down his face as he smiles. The house is then shown to be a dilapidated empty home.

Production

Whilst series one and two of Black Mirror were shown on Channel 4 in the UK, in September 2015 Netflix commissioned the series for 12 episodes (split into two series of six episodes).[2] In March 2016, Netflix outbid Channel 4 for the rights to distributing the third series, with a bid of $40 million.[3] Due to its move to Netflix, the show had a larger budget than in previous series.[4] "Men Against Fire" is the fifth episode of the third series;[5] all six episodes in this series were released on Netflix simultaneously on 21 October 2016. As Black Mirror is an anthology series, each episode is standalone.[6]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The trailer for series three of Black Mirror |

The titles of the six episodes that make up series 3 were announced in July 2016, along with the release date.[7] A trailer for series three, featuring an amalgamation of clips and sound bites from the six episodes, was released by Netflix on 7 October 2016.[8]

Conception and writing

The episode was written by series creator Charlie Brooker. Originally called "Inbound", the first draft was inspired by the 2010 documentary The War You Don't See, which featured lengthy stories from victims of the Iraq War. In "Inbound", an attack on Britain appeared to be from an alien force, but was later revealed to be an invasion by Norway. It was the second script pitched in 2010 for the first series of Black Mirror, but it was rejected at the time. Influenced by Men Against Fire: The Problem of Battle Command by S.L.A. Marshall and On Killing by Dave Grossman, the episode's focus gradually shifted to a war where combat is censored to soldiers, and it was renamed "Men Against Fire".[1]

The title of the episode comes from Brigadier General S.L.A. Marshall's book Men Against Fire: The Problem of Battle Command (1947), wherein Marshall claims that during World War II, over 70% of soldiers did not fire their rifles, even under immediate threat, and most of those who fired aimed above the enemy's head.[9] A similar statement is made during one of Arquette's dialogues in the episode.[10] TheWrap later reported that there have been suggestions that Marshall's claim is incorrect.[11] For research, Brooker also read Dave Grossman's book On Killing, which is about the psychology of killing and based on Marshall's work.[12][10] He initially wrote Arquette as more "stuffy", though his character was always intended to be sympathetic. He is a father figure to some of the soldiers, and thinks his actions are good.[1]

Casting and filming

Jakob Verbruggen directed the episode.[1] Malachi Kirby, a fan of the programme, was cast as Stripe. Kirby played the character as naive, vulnerable and with a sense of doubt, rather than as an alpha male.[1] Michael Kelly plays psychologist Arquette, having previously worked with Verbruggen on the American political thriller House of Cards. Kelly believed that Arquette and Doug Stamper—his character on House of Cards—had a commonality of "true convictions in their actions". He suggested that Arquette thinks his actions help soldiers cope with posttraumatic stress disorder.[13]

The episode was filmed in 18 days. He was inspired by the "fearless high energy" of the 1997 science fiction film Starship Troopers. Though intended to look "gritty" and foreign, perhaps in an Eastern European setting, the production was constrained to the United Kingdom for economy of time and budget. Two locations near London were used for filming: the first was a disused army barracks, and the second was a set constructed in the forest for use as the village setting. A farmhouse was used as the "roach nest".[1]

As the roaches were to be shown close up to the camera, their design was considered in detail. Their clothing was ill-fitted, to look like it had been taken from villages. After looking at the effects of skin diseases and mutations, production designer Joel Collins conceived of a design in which their brains and features had swelling, as if they had hydrocephalus. Kristyan Mallett worked on prosthetics, and four designs were tested on camera. The actors required hours in make-up for prosthetics. Adult actors were given black contact lenses, while the eyes of a young boy featured were altered using visual effects in post-production. As the story only made sense if the fight scene in the farmhouse was shown from a soldier's point of view, the scene was shot in a frantic style, and roaches appeared more human-like when viewed from behind.[1]

Body doubles were used for the effect of Stripe seeing three copies of his fiancée as his MASS malfunctions during a dream.[1] Kelly's two scenes were filmed across three days, the latter being a lengthy scene where Stripe and Arquette are alone in a cell together. Kelly spent the second day thoroughly rehearsing this scene repeatedly, and it was filmed on the third day.[13] The room was chosen to be "bright, uncomfortable and extremely claustrophobic", and the two characters are never shown in the same frame; as Stripe learns information, the room feels like it closes in on him.[1]

Analysis

Both Kelly and executive producer Annabel Jones compared the episode to what they saw as rising xenophobia in Europe and America, exemplified by media descriptions of refugees as "swarms" of people, the Donald Trump 2016 presidential campaign and Brexit coverage.[13][15] These comparisons were also made by critics:[16][17] Matt Patches of Thrillist summarised the episode as a "catch-all metaphor for how we deal with the disenfranchised members of our global society",[18] whilst Christian Holub of Entertainment Weekly described it as a "thought-provoking parable about the military's role in genocide".[14] Tristram Fane Saunders of The Telegraph believed compassion to be the message of the episode.[16]

The episode was described by reviewers as analogous to Nazi Germany and the Holocaust.[17][14][19] Sophie Gilbert of The Atlantic commented that the episode's depiction of eugenics links to "prejudices still rife among humankind" such as "institutionalized racism, tribalism, and fear of refugees".[20] Alissa Wilkinson of Vox found that the episode was about the past rather than the future, as it explores crimes against humanity from 20th century history.[19] Andrew Liptak of The Verge wrote that in the episode, the "government perpetuated a holocaust by literally demonizing its enemies".[21] Several reviewers noted that the villagers in the episode do not have the MASS system, so they see the genocide victims as they are, but still consider them "roaches".[17][19][20]

Verbruggen said that the ending, in which Stripe appears to come home to a beautiful house and fiancée, but then the house is seen to be empty and derelict, can be interpreted in different ways by the audience. Kirby suggested an interpretation where Stripe chooses to keep his memories, but enable the MASS system, so he knows his vision is a lie.[1] Kelly opined that Stripe had his memories wiped and that the house being empty is seen only by the viewers, not by Stripe.[13] Verbruggen questions whether any of the episode's events are real. Brooker called the ending "oblique", saying that he did not have an answer to what the ending meant. The ending was originally conceived of as a homecoming parade for the returning soldiers, which is revealed to not be real.[1]

"Men Against Fire" has been compared to other works of science fiction. Alex Mullane of Digital Spy and Charles Bramesco of Vulture made comparisons with the 1997 satirical film Starship Troopers, for the soldiers' "macho talk of ending the Roach menace" and the work's "thinly veiled commentary on the culture of virulence that warring nations have to cultivate".[17][22] The episode was also described as the episode of Black Mirror most similar to The Twilight Zone, the anthology series which inspired it, for its focus on one simple parable.[16][14] Liptak compared the episode's narrative of a soldier realising the damage he is inflicting and going through a personal crisis to the military-related works "Enemy Mine", a 1979 novella, and Captain America: The Winter Soldier, a 2014 film.[21]

A Den of Geek article compares several real-world technologies to features of the MASS tool. Applied Research Associates' product ARC4 is an augmented reality headset designed for soldiers, whilst Waverly Labs has an app and earpiece translation tool designed for conversation, and a product "iBand+" in development claims it will be able to induce lucid dreaming.[23]

Reception

On Rotten Tomatoes, the episode received a rating of 57%, based on 21 reviews, indicating mixed reception.[5] The episode received an A– rating by Zack Handlen of The A.V. Club,[24] a B– grade from Christian Holub of Entertainment Weekly[14] and a score of three out of five stars in Tristram Fane Saunder's review for The Telegraph.[16] Roxanne Sancto of Paste praised the episode as "incredibly fucking relevant"[25] and Gilbert said it was "one of the better episodes of the series",[20] but Matt Fowler of IGN wrote that it was the "least engaging emotionally" in the third series[26] and Adam Chitwood of Collider criticised it as "heavy-handed with its social commentary".[27] Both Liptak and Bramesco believed the concepts to be interesting, but executed poorly.[21][22] However, Handlen praised the episode's pacing.[24]

The plot twist was widely considered to be predictable,[22][24][27] leading Wilkinson and Mullane to say that the episode was not shocking[17][19] and Wilkinson to say that it lacked tension.[19] However, Gilbert described the twist as "terrific" and "unexpected", praising its plausibility.[20] Handlen described the ending of the episode as "slightly unclear", albeit symbolically "effective".[24] Saunders enjoyed the scene with Stripe and Arquette alone in a cell, commenting that them "discussing ideas of right and wrong" was "by far the finest part of the episode".[16]

Kirby and Kelly were both praised for their performances as Stripe and Arquette, respectively.[17][20] Handlen noted that Stripe is a passive character, and opined that Kirby did a good job in keeping "our interest and our sympathies" throughout the episode.[24] Bramesco believed that Kirby's performance introduced "a grounded component worthy of the audience's emotional investment" to the episode.[22] Gilbert praised that Kelly "imbues every performance with extraordinary menace".[20] Sancto praised the scene in which Stripe and Catarina—the mother labelled as a "roach"—converse.[25]

The episode was criticised for overreliance on cliches, particularly those relating to the military and dystopic science fiction.[21][14] Saunders wrote that the episode's portrayal of the military was "competent and familiar, rather than fresh or exciting".[16] Bramesco said the episode was too much of a "simplistic metaphor" and "doesn't offer anything new".[22] Mullane wrote that "there a few shots where the boom mic slips into frame, which is an uncharacteristically sloppy distraction".[17] Bramesco opined that the episode was "gratuitously violent".[22]

For their work on this episode, Kristyan Mallett and Tanya Lodge were nominated for a 2017 Make-Up Artists and Hair Stylists Guild award, in the category of Best Special Makeup Effects – Television Mini-Series or Motion Picture Made for Television.[28]

Black Mirror episode rankings

"Men Against Fire" appeared on many critics' rankings of the 23 instalments in the Black Mirror series, from best to worst.

|

|

IndieWire authors ranked the 22 Black Mirror instalments excluding Bandersnatch by quality, giving "Men Against Fire" a position of 18th.[37] Additionally, Proma Khosla of Mashable ranked the same instalments by tone, concluding that "Men Against Fire" was the eighth most bleak.[38] Eric Anthony Glover of Entertainment Tonight ranked the episode 15th out of the 19 episodes from series one to four.[39]

Other critics ranked the 13 episodes in Black Mirror's first three series.

- 6th – Andrew Wallenstein, Variety[40]

- 11th – Adam David, CNN Philippines[41]

- 12th – Jacob Hall, /Film[42]

- 12th – Mat Elfring, GameSpot[43]

Some critics ranked the six episodes from series three of Black Mirror in order of quality.

- 6th – Jacob Stolworthy and Christopher Hooton, The Independent[44]

- 6th – Liam Hoofe, Flickering Myth[45]

See also

- "Hearts and Minds" – a 1998 episode of the anthology series The Outer Limits with a similar premise

- The 5th Wave (film) – science-fiction film where people are also manipulated with implants to kill other people

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Brooker, Charlie; Jones, Annabel; Arnopp, Jason (November 2018). "Men Against Fire". Inside Black Mirror. New York City: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 9781984823489.

- ^ Birnbaum, Debra (25 September 2015). "'Black Mirror' Lands at Netflix". Variety. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ Plunkett, John (29 March 2016). "Netflix deals Channel 4 knockout blow over Charlie Brooker's Black Mirror". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ "Black Mirror review – Charlie Brooker's splashy new series is still a sinister marvel". The Guardian. 16 September 2016. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Black Mirror – Season 3, Episode 5". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Stolworthy, Jacob (21 October 2016). "Black Mirror creator Charlie Brooker: 'I'm loath to say this is the worst year ever because the next is coming'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ Lutes, Alicia (27 July 2016). "Black Mirror's New Episodes Will Hit US In October". Nerdist Industries. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Kelley, Seth (7 October 2016). "'Black Mirror' Season 3 Trailer Teases Six 'New Realities'". Variety. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Men Against Fire: How Many Soldiers Actually Fired Their Weapons at the Enemy During the Vietnam War". Historynet.com. 12 June 2006. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Black Mirror postmortem: Showrunner talks season 3 twists". Entertainment Weekly. 21 October 2016. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ Molloy, Tim (26 October 2016). "'Black Mirror' Fact Check: Do Most Soldiers Really Not Shoot?". TheWrap. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Mechanic, Michael (14 October 2016). "The Man Behind Netflix's "Black Mirror" Is Maybe a Little Too Good at Predicting the Future". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Strause, Jackie (1 November 2016). "'Black Mirror' Star Michael Kelly on Donald Trump and "Incredibly Relevant" War Message". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Holub, Christian (24 October 2016). "'Black Mirror' recap: Season 3, Episode 5, Men Against Fire". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Harnick, Chris (28 October 2016). "Michael Kelly on Why Black Mirror's "Men Against Fire" Is Timely". E!. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Saunders, Tristram Fane (24 October 2016). "Black Mirror, Season 3, Men Against Fire, review: 'an urgent moral message'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mullane, Alex (23 October 2016). "Black Mirror season 3 'Men Against Fire' review: a quietly effective tale of prejudice". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Patches, Matt (23 October 2016). "We're Basically Living the 'Men Against Fire' Episode of 'Black Mirror' Already". Thrillist. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Wilkinson, Alissa (21 October 2016). "Black Mirror season 3, episode 5: "Men Against Fire" is a warning from the past about our future". Vox. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Gilbert, Sophie (22 October 2016). "Black Mirror's 'Men Against Fire' Tackles High-Tech Warfare". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d Liptak, Andrew (27 October 2016). "In Men Against Fire, Black Mirror takes on the future of warfare". The Verge. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Bramesco, Charles (21 October 2016). "Black Mirror Recap: Know Your Enemy, Know Why You Fight". Vulture. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Leane, Rob (3 November 2016). "How Black Mirror Season 3 Is Eerily Coming True". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Handlen, Zack (25 October 2016). "Someone builds a better soldier on an unsettling Black Mirror". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b Sancto, Roxanne (27 October 2016). "Black Mirror's "Men Against Fire" Is a Chilling Political Allegory for an Anti-Immigrant Age". Paste. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Fowler, Matt (19 October 2016). "Black Mirror: Season 3 Review". IGN. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b Chitwood, Adam (21 October 2016). "'Black Mirror' Season 3 Review: The Future Is Slightly Sunnier on Netflix". Collider. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Giardina, Carolyn (19 February 2017). "Daytime Television: Best Hair Styling – 'Suicide Squad,' 'Star Trek Beyond' Among Winners at Makeup Artists and Hair Stylists Guild Awards". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Donnelly, Matt; Molloy, Tim (8 June 2019). "'Striking Vipers' to 'National Anthem': Every 'Black Mirror' Ranked, From Good to Mind-Blowing (Photos)". TheWrap. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Power, Ed (5 June 2019). "Black Mirror: every episode ranked and rated, from Striking Vipers to San Junipero". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Atad, Corey (5 June 2019). "Every Episode of Black Mirror, Ranked". Esquire. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Hibberd, James (5 June 2019). "Every Black Mirror Episode Ranked (including season 5)". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Bramesco, Charles (5 June 2019). "Every Black Mirror Episode, Ranked". Vulture. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Jeffery, Morgan; Fletcher, Rosie (13 June 2019). "Ranking all 23 episodes of Charlie Brooker's chilling Black Mirror". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ Page, Aubrey (14 June 2019). "Every 'Black Mirror' Episode Ranked From Worst to Best". Collider. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Clark, Travis (10 June 2019). "All 23 episodes of Netflix's 'Black Mirror,' ranked from worst to best". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Greene, Steve; Nguyen, Hanh; Miller, Liz Shannon (24 November 2017). "Every 'Black Mirror' Episode Ranked, From Worst to Best". IndieWire. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Khosla, Proma (5 January 2018). "Every 'Black Mirror' episode ever, ranked by overall dread". Mashable. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Glover, Eric Anthony (22 December 2017). "Every 'Black Mirror' Episode Ranked, From Worst to Best". Entertainment Tonight. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Wallenstein, Andrew (21 October 2016). "'Black Mirror' Episodes Ranked: Spoiler-Free Guide to Seasons 1–3". Variety. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ David, Adam (24 October 2016). "How to watch all 'Black Mirror' episodes, from worst to best". CNN Philippines. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Hall, Jacob (28 October 2016). "Through a Touchscreen Darkly: Every 'Black Mirror' Episode Ranked". /Film. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Elfring, Mat (28 October 2016). "Black Mirror: Every Episode Ranked From Good to Best". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Stolworthy, Jacob; Hooton, Christopher (21 October 2016). "Black Mirror review: The season 3 episodes, ranked". The Independent. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Hoofe, Liam (29 October 2016). "Ranking Black Mirror Season 3 Episodes from Worst to Best". Flickering Myth. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

External links

- 2016 British television episodes

- Black Mirror episodes

- Augmented reality in fiction

- Television episodes about eugenics

- Television episodes about dreams

- Drones in fiction

- Fiction with unreliable narrators

- Military science fiction television episodes

- Television episodes written by Charlie Brooker

- Netflix original television series episodes