.30-06 Springfield wildcat cartridges

| Parent Cartridge .30-06 Springfield | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Rifle | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In service | 1906 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Used by | USA and others | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wars | World War I, World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Production history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designer | Springfield Armory | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designed | 1906 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Produced | 1906-present | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Specifications | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent case | .30-03 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Case type | Rimless, bottleneck | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bullet diameter | 7.62 mm (0.300 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

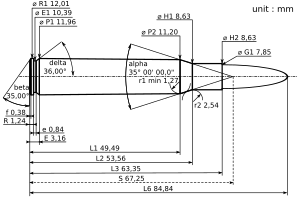

| Neck diameter | 8.63 mm (0.340 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shoulder diameter | 11.20 mm (0.441 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Base diameter | 11.96 mm (0.471 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rim diameter | 12.01 mm (0.473 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rim thickness | 1.24 mm (0.049 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Case length | 63.35 mm (2.494 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overall length | 84.84 mm (3.340 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Case capacity | 4.43 cm3 (68.4 gr H2O) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rifling twist | 254 mm (1 in 10 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Primer type | Large rifle | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maximum pressure | 405 MPa (58,700 psi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ballistic performance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test barrel length: 24 inch Source(s): Federal Cartridge[1] / Accurate Powder[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

.30-06 Springfield wildcat cartridges are cartridges developed from a 30-06 Springfield "parent cartridge" through narrowing or widening the cartridge neck to fit a smaller or larger bullet in an attempt to improve performance in specific areas.[3] Such wildcat cartridges are not standardized with recognized small arms standardization bodies like the SAAMI and the CIP.[4][5][3]

Side note☆☆ the .280 Remington was NOT stamped 7mm-06, or square or anything else besides ☆☆☆ 7mm Express☆☆☆ n yes it was changed due to confusion. One of the 1st Rifles produced for this round was Remington 's 742 autoloader, n the 762 pump. It is stamped from manufacture 7mm EXP. on barrel, but we know know it as the .280 Remington

Parent cartridge

The 30-06 Springfield cartridge (pronounced “thirty-ought-six”, "thirty-oh-six") or 7.62×63mm in metric notation, was introduced to the United States Army in 1906 (hence “06”) where it was in use until the early 1970s. It remains a very popular sporting round, with ammunition produced by all major manufacturers.

It has a 68.2 grains (4.43 ml ) H2O cartridge case capacity. The exterior shape of the case was designed to promote reliable case feeding and extraction under extreme conditions for both bolt-action rifles and machine guns.

30-06 Springfield maximum C.I.P. cartridge dimensions. All sizes in millimeters (mm).

Wildcats

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: the article contains opinions and comments about the efficiency of the various cartridges. (November 2014) |

There have been a large number of .30-06 Springfield-based wildcat cartridges produced, including:

22-06 (also 223-06) - necked down to accept a .224 caliber bullet - The 22-06 uses the same caliber bullet as the 223 Remington. This round is frequently used for varmint hunting, offering the shooter a long range, high-velocity, and therefore flat shooting, chambering suitable for that sport. The similar 226 Express, in addition to reducing neck diameter, reduces shoulder diameter to impose a long, slender body taper on the 30-06 case.[6] Extensive experimentation during the mid-20th century indicated no practical benefit from the incremental volume increase of the 63 mm-long 30-06 case over the 57 mm-long 7mm Mauser case for .22 caliber bullets.[7]

6mm-06 (also 243-06) - necked down to accept a .243 bullet - Once considered significantly overbore, proponents of the 6mm-06 chambering argue the cartridge is more practical following the development and availability of slower burning powders capable of exploiting the larger case capacity.[8][9] The cartridge has greater capacity than either the 243 Winchester or the 6mm Remington, slightly more capacity than the 240 Weatherby Magnum, and slightly less capacity than 6mm-284 wildcat cartridge.[9] The 6mm-06 can drive a 105 grain .243 caliber projectile in excess of 3200 feet per second (fps), giving the 6mm-06 a ballistic advantage over the non-magnum .243 offerings from Winchester and Remington, particularly at longer ranges.[8][9] Due to the wide availability of inexpensive parent cases, the 6mm-06 is also less expensive than comparable long-range performers like the 240 Weatherby Magnum and the 6mm-284.[8][9]

243 Catbird - 270 Winchester necked down to a .243 bullet with the shoulder blown out (angle increased) to 35 degrees - The 270 Winchester is a standardized cartridge of the same design as the 30-06 except the case is 1.2mm longer and necked down to the .270 caliber. Therefore, the 243 Catbird is a 6mm-06 with a 35 degree shoulder and a 1.2mm longer case.[10] The .243 Catbird was developed by Kenny Jarrett of Jarrett Rifles to achieve 4000 fps with a 68-70 grain bullet.[10][11] Actual performance tests showed the cartridge achieved 4100 fps with a 70 grain bullet, 3800 fps with an 85 grain bullet, and 3500 fps with a 95 grain projectile.[10] Jarrett describes the chambering as a "barrel burner" with a barrel maintaining accuracy for about 1500 rounds.[10]

25-06 - necked down to accept a .25 bullet - The 25-06 was a wildcat cartridge for nearly 50 years before Remington Arms "tamed" it in 1969 through standardization and marketed the cartridge commercially as the 25-06 Remington.

6.5-06 (or 6.5mm/06) - necked down to accept a 6.5 mm bullet - The 6.5-06 offers ballistic performance between the commercialized 25-06 Remington and 270 Winchester with distinct advantages over both in particular long-range applications through a wide selection of bullets with high ballistic coefficients producing better extended range performance.[12][13][14] This chambering was standardized as the 6.5-06 A-Square with SAAMI in 1997 by the A-Square Company, a manufacturer of arms and ammunition based in the United States. Over 80 years earlier, a nearly identical cartridge was commercially marketed as the 256 Newton.[13] The 256 Newton suffered from a lack of slower burning powders capable of taking advantage of the large case capacity.[13] Munitions manufacturers ceased making the 256 Newton in 1938, 20 years after the firearms company built by Charles Newton, who created the cartridge, went bankrupt.[13] There are small dimensional differences between the .256 Newton and 6.5-06 later standardized by A-Square: the 256 Newton has an increased body taper, the shoulder is moved back, and has a sharper, 23 degree shoulder while the 6.5-06 has a 17.5 degree shoulder like the parent 30-06 case. SAAMI lists the 6.5-06 A-Square in the Centerfile Rifle Cartridge and Chamber Drawing table dated June 3, 2012, and the 6.5-06 drawing was still available from SAAMI as of March 2018.[15] The 2015 comprehensive American National Standards Institute (ANSI)/SAAMI standard ANSI/SAAMI Z299.4 for centerfire rifle ammunition no longer includes the 6.5-06 A-Square cartridge. A-Square went bankrupt in 2012 and no major manufacturer makes loaded ammunition or brass cases for the 6.5-06 in March 2018.

7mm-06 - necked down to accept a 7mm bullet - Originated during experimentation with 7mm bullets in inexpensive, surplus 30-06 brass cases.[16] The commercial .280 Remington (or 7mm Express Remington) is very similar, but uses the slightly longer 65 mm 30-03 case with the shoulder headspace extended slightly more than one millimeter (.05 inch) to prevent chambering in 270 Winchester rifles.[17] Early Remington in-house developmental rounds were headstamped R-P 7MM-06 REM but, to avoid confusion with similarly named wildcats, the headstamp was changed to 280 REM.[citation needed]

8mm-06 - necked up to accept an 8mm bullet - The 8mm-06 allows owners of military surplus 7.92×57mm Mauser rifles to fire 8mm bullets using inexpensive, surplus 30-06 brass cases without rebarreling their rifle, only a rechambering is necessary.[16]

.338-06 - necked up to accept a .338 bullet - The 338-06 gives shooters the option of using heavier bullets for bigger game while suffering less recoil than other .338 caliber cartridges. The 338-06 chambering was a popular wildcat dating back to the late 1950s.[18][19] The cartridge was standardized as the 338-06 A-Square with SAAMI in 1998 by the A-Square Company.[18][19] Weatherby briefly offered some models of rifles chambered in 338-06 A-Square.[18][19] The 338-06 is a practical, flexible, and potent medium bore cartridge offering substantially similar performance to the prototype 338 Winchester Short Magnum later released as the 325 Winchester Short Magnum while producing less stress on the bullet and shooter than a magnum cartridge. SAAMI lists the 338-06 A-Square in the Centerfire Rifle Cartridge and Chamber Drawing table dated June 3, 2012, and the 338-06 drawing was still available from SAAMI as of March 2018.[20] The 2015 comprehensive ANSI/SAAMI standard ANSI/SAAMI Z299.4 for centerfire rifle ammunition no longer includes the 338-06 A-Square cartridge. Nosler was still producing 338-06 A-Square ammunition under their "Custom Nosler" label in March 2018.[21]

35-06 - necked up to accept a .35 bullet - Now standardized and marketed as the 35 Whelen, this cartridge was intended to create a cartridge suitable for bigger and potentially dangerous game, specifically African game, on standard length actions with relatively inexpensive components (i.e. 30-06 brass cases).[22]

375-06 - necked up to accept a .375 bullet - Also known as the 375 Whelen, this wildcat was another effort to use standard actions and inexpensive, surplus cases with heavier bullets.[citation needed] The 375 Whelen Improved sharpens the 30-06 shoulder for more reliable headspace.[citation needed]

400-06 - necked up to accept a 405 Winchester bullet. Better known as the 400 Whelen. Griffin & Howe chambered rifles for this cartridge, but headspace difficulties were reported with the small shoulder.[23]

Ackley Improved - P.O. Ackley was a notable gunsmith famous for developing wildcat cartridges from parent cartridges like the 30-06 Springfield. For many of the wildcats listed above, and several of standardized commercial chamberings based on the 30-06 cartridge, there are "Ackley Improved" versions with sharper shoulders increasing case capacity.[24] These versions are noted by the letters "AI" after the cartridge name (e.g. 6.5-06 AI, 30-06 AI, etc.).[24] Nosler registered the .280 Ackley Improved with SAAMI and produces loaded ammunition.

Gibbs Cartridges - R.E. "Rocky" Gibbs was a firearms experimenter and gunsmith based in Viola, Idaho in the 1950s.[3] He developed a series of improved cartridges for chamberings derived from the 30-06 Springfield, including the 25 Gibbs, 6.5mm Gibbs, 270 Gibbs, 7mm Gibbs, 30 Gibbs, and 8mm Gibbs by blowing out the case, pushing the shoulder forward, and increasing the angle of the shoulder.[3]

See also

- Hydrostatic shock

- Caliber conversion sleeve

- List of rifle cartridges

- Table of pistol and rifle cartridges

- 7 mm caliber

- .303 British

- Delta L problem

- Sectional density

References

- ^ "Federal Cartridge Co. ballistics page". Archived from the original on 22 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ^ "Accurate Powder reload data table" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-20. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ^ a b c d Frank C. Barnes; M.L. McPherson, eds. (1997). Cartridges of the world (8th, rev. and expanded ed.). Northbrook, IL: DBI Books. ISBN 978-0-87349-178-5.

- ^ "Small Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute". Small Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute. Small Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ "Commission internationale permanente pour l'épreuve des armes à feu portatives". Commission internationale permanente pour l'épreuve des armes à feu portatives. Commission internationale permanente pour l'épreuve des armes à feu portatives. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Sharpe, Philip B. Complete Guide To Handloading (Funk & Wagnalls, 1953 ), p.351.

- ^ Landis, Charles S. Twenty-Two Caliber Varmint Rifles (Small Arms Technical Publishing Company, 1947)[page needed]

- ^ a b c Chuck, Hawks. "The 6mm-06". Guns & Shooting Online. Chuck Hawks. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Layne, Simpson (4 January 2011). "6mm-06 Wildcat". Rifle Shooter Mag. Guns & Ammo Network. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Kenny, Jarrett. "Kenny Jarrett's Pet Calibers". Jarrett Rifles. Jarrett Rifles. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ van Zwoll, Wayne (2013). Mastering the Art of Long-Range Shooting. Gun Digest Books. p. 62. ISBN 978-1440234651.

- ^ Ackley, P.O. (1927) [1962]. Handbook for Shooters & Reloaders. vol I (12th Printing ed.). Salt Lake City, Utah: Plaza Publishing. pp. 363–364. ISBN 978-99929-4-881-1.

- ^ a b c d ".256 Newton and 6.5-06". Terminal Ballistics Research. Terminal Ballistics Research. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Chuck, Hawks. "The 6.5mm-06 A-Square Rifle Cartridge". Guns & Shooting Online. Chuck Hawks. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "SAAMI 6_5-06 A-Square" (PDF). Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute. SAAMI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-22. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ a b Speer, Raymond G. Wildcat Rifle Loads (Speer Products Company, 1956) p.81

- ^ Davis, William C. Jr. (1981). Handloading. National Rifle Association. pp. 180–181. ISBN 0-935998-34-9.

- ^ a b c Chuck, Hawks. "The 338-06 A-Square". Guns & Shooting Online. Chuck Hawks. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ a b c ".338-06 A-Square". Terminal Ballistics Research. Terminal Ballistics Research. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "SAAMI 338-06 A-SQUARE" (PDF). Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute. SAAMI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-22. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Nosler. "Nosler Custom Ammunition". Nosler. Nosler. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ Speer Reloading Manual (8 ed.). Lewiston, Idaho: Speer Products Company. 1970. pp. 305, 306. ASIN B000VXVJJM.

- ^ Sharpe, Philip B. Complete Guide To Handloading (Funk & Wagnalls, 1953) pp.206&398

- ^ a b Ackley, P.O. "P.O. Ackley: His Life and Work". Ackley Improved. Estate of P.O. Ackley. Retrieved 24 March 2018.