Roanoke, Virginia

Parts of this article (those related to Demographics) need to be updated. (October 2018) |

Roanoke, Virginia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s): The Star City of The South, Magic City, Star City | |

| Coordinates: 37°16′15″N 79°56′30″W / 37.27083°N 79.94167°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | None (Independent city) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager see Roanoke City Council |

| • Mayor | Sherman P. Lea Sr. (D) |

| • Vice Mayor | Patricia White-Boyd |

| Area | |

| 42.85 sq mi (110.99 km2) | |

| • Land | 42.52 sq mi (110.13 km2) |

| • Water | 0.33 sq mi (0.86 km2) |

| Elevation | 883–1,740 ft (269–530 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| 100,011 | |

| • Rank | 326th in the United States 8th in Virginia |

| • Density | 2,352/sq mi (900.24/km2) |

| • Urban | 210,111 (US: 173rd) |

| • Metro | 315,251 (US: 163rd) |

| Demonym | Roanoker |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 24001–24020, 24022–24038, 24040, 24042–24045, 24048, 24050, 24155, 24157, 24012 |

| Area code | 540 |

| FIPS code | 51-77000[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1499971[5] |

| Primary Airport | Roanoke–Blacksburg Regional Airport |

| Website | www.roanokeva.gov |

Roanoke (/ˈroʊənoʊk/ ROH-ə-nohk) is an independent city in the U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 100,011,[6] making it the 8th most populous city in Virginia and the largest city in Virginia west of Richmond. It is located in the Roanoke Valley of the Roanoke Region of Virginia.[7]

Roanoke is the largest municipality in Southwest Virginia, and is the principal municipality of the Roanoke Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), which had a 2020 population of 315,251. It is composed of the independent cities of Roanoke and Salem, and Botetourt, Craig, Franklin, and Roanoke counties. Bisected by the Roanoke River, Roanoke is the commercial and cultural hub of much of Southwest Virginia and portions of Southern West Virginia.[8]

History

Timeline

- 1835 - Town of Gainesborough incorporated.[9]

- 1838 - Roanoke County created.[10]

- 1852 - Big Lick Depot built near Gainesborough; Virginia & Tennessee Railroad begins operating.[11]

- 1865 - April: Big Lick settlement sacked by Federal forces during American Civil War.[11]

- 1870 - Atlantic, Mississippi & Ohio Railroad begins operating.

- 1874

- 1878 - Big Lick News begins publication.[13]

- 1882

- Big Lick and Old Lick renamed "Roanoke".[12]

- Roanoke Machine Works in business.[14]

- Population: 5,276.[14]

- 1883 - YMCA branch founded.[15]

- 1884 - City of Roanoke incorporated.[16]

- 1885 - Municipal market established.[13]

- 1886 - Roanoke Daily Times newspaper begins publication.[17]

- 1889 - Evening World newspaper begins publication.[17]

- 1890

- Roanoke Hospital founded.[15]

- Population: 16,159.

- 1891 - Roanoke Weekly Press newspaper begins publication.[18]

- 1893 - September 20: "Lynch riot" occurs.[11][18]

- 1902 - Beth Israel congregation formed.[19]

- 1903 - Agricultural "Great Roanoke Fair" begins.[14]

- 1904 - Chamber of Commerce founded.[14]

- 1906 - Virginian Railway begins operating.[13]

- 1910

- City Health Department established.[15]

- Mill Mountain Incline (funicular) begins operating.[13]

- Population: 34,874.

- 1911 - Roanoke Theatre in business.[20]

- 1913 - Bijou Theatre in business.[20]

- 1914 - YWCA branch founded.[15]

- 1919 - "Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court" established.[15]

- 1920 - Population: 50,842.[15]

- 1921

- Public Library opens.[13]

- Ku Klux Klan branch active (approximate date).[21][chronology citation needed]

- 1924 - WDBJ radio begins broadcasting.[22]

- 1925 - Patrick Henry Hotel in business.

- 1926 - Memorial Bridge opens.

- 1930 - Big Lick Garden Club formed.[13]

- 1933 - Roanoke Municipal Airport begins operating.

- 1936 - First Dr. Pepper plant east of the Mississippi River opened by John William "Bill" Davis; Roanoke soon becomes the Dr. Pepper Capitol of the World [23]

- 1939 - Roanoke Tribune newspaper begins publication.

- 1950 - Population: 91,921.

- 1952

- WSLS-TV (television) begins broadcasting.[24]

- Mill Mountain Zoo established.[25]

- 1955 - WDBJ-TV (television) begins broadcasting.[24]

- 1957 - Roanoke Historical Society founded.[26]

- 1959 - Temple Emanuel Synagogue built.[19]

- 1966 - Virginia Western Community College established.

- 1976 - Portion of Roanoke County becomes part of city.[12]

- 1980 - Population: 100,220.

- 1985 - Valley View Mall in business.

- 1992 - David A. Bowers becomes mayor.[27]

- 1993 - Bob Goodlatte becomes U.S. representative for Virginia's 6th congressional district.[28]

- 2000 - City website online (approximate date).[29]

- 2004 - O. Winston Link Museum opens.

- 2010 - Population: 97,032.[30]

- 2016

- October 25: FreightCar America shooting occurs.

- Sherman P. Lea becomes mayor.[27]

Incorporation

First called Big D, after a large outcropping of salt that drew the wildlife to the site near the Roanoke River,[31] the town was established in 1852 and chartered in 1874. In 1882, Big Lick became the town of Roanoke, and in 1884, it was chartered as the independent city of Roanoke. The name Roanoke is said to have originated from an Algonquian word for "shell money",[32] which was the name used for the river by the Algonquian speakers who lived 300 miles (480 km) away, where the river emptied into the sea near Roanoke Island. The native people who lived near where the city was founded did not speak Algonquian. They spoke Siouan languages, Tutelo, and Catawban. There were also Cherokee speakers in the general area who fought with the Catawba people. The city grew frequently via annexation through the middle of the 20th century.[33] The last annexation was in 1976. The state legislature has since prohibited cities from annexing land from adjacent counties. Roanoke's location in the Blue Ridge Mountains, in the middle of the Roanoke Valley between Maryland and Tennessee, made it the transportation hub of western Virginia and contributed to its rapid growth.

Colonial influence

During colonial times, the site of Roanoke was an important hub of trails and roads. The Great Indian Warpath, which later merged into the colonial Great Wagon Road, was one of the most heavily traveled roads of 18th-century America. It ran from Philadelphia through the Shenandoah Valley to the future site of Roanoke, where the Roanoke River passed through the Blue Ridge. The Carolina Road branched off in Cloverdale, Virginia, to Boones Mill, Virginia, and on to the Yadkin River Valley. The Roanoke Gap proved a useful route for immigrants to settle the Carolina Piedmont region. At Roanoke Gap, another branch of the Great Wagon Road, the Wilderness Road, continued southwest to Tennessee.

Railroads and coal

In the 1850s, Big Lick became a stop on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad (V&T) which linked Lynchburg with Bristol on the Virginia-Tennessee border.

After the American Civil War (1861–1865), William Mahone, a civil engineer and hero of the Battle of the Crater, was the driving force in the linkage of three railroads, including the V&T, across the southern tier of Virginia to form the Atlantic, Mississippi & Ohio Railroad (AM&O), a new line extending from Norfolk to Bristol, Virginia in 1870. However, the Financial Panic of 1873 wrecked the AM&O's finances. After several years of operating under receiverships, Mahone's role as a railroad builder ended in 1881 when northern financial interests took control. At the foreclosure auction, the AM&O was purchased by E.W. Clark & Co., a private banking firm in Philadelphia which controlled the Shenandoah Valley Railroad then under construction up the valley from Hagerstown, Maryland. The AM&O was renamed Norfolk and Western Railway (N&W).

Frederick J. Kimball, a civil engineer and partner in the Clark firm, headed the new line and the new Shenandoah Valley Railroad. For the junction for the Shenandoah Valley and the Norfolk and Western roads, Kimball and his board of directors selected the small Virginia village called Big Lick, on the Roanoke River. Although the grateful citizens offered to rename their town "Kimball", at his suggestion, they agreed to name it Roanoke after the river. As the N&W brought people and jobs, the Town of Roanoke quickly became an independent city in 1884. In fact, Roanoke became a city so quickly that it earned the nickname "Magic City".

Kimball's interest in geology was instrumental in the development of the Pocahontas coalfields in western Virginia and West Virginia. He pushed N&W lines through the wilds of West Virginia, north to Columbus, Ohio and Cincinnati, Ohio, and south to Durham, North Carolina, and Winston-Salem, North Carolina. This gave the railroad the route structure it was to use for more than 60 years.

The Virginian Railway (VGN), an engineering marvel of its day, was conceived and built by William Nelson Page and Henry Huttleston Rogers. Following the Roanoke River, the VGN was built through the City of Roanoke early in the 20th century. It merged with the N&W in 1959.

The opening of the coalfields made N&W prosperous and Pocahontas bituminous coal world-famous. Transported by the N&W and neighboring Virginian Railway (VGN), local coal-fueled half the world's navies. Today it stokes steel mills and power plants all over the globe.

The Norfolk & Western was famous for manufacturing steam locomotives in-house. It was N&W's Roanoke Shops that made the company known industry-wide for its excellence in steam power. The Roanoke Shops, with its workforce of thousands, is where the famed classes A, J, and Y6 locomotives were designed, built, and maintained. New steam locomotives were built there until 1953, long after diesel-electric had emerged as the motive power of choice for most North American railroads. About 1960, N&W was the last major railroad in the United States to convert from steam to diesel power. When N&W converted to diesel power, 2,000 railroad workers were laid off.[34]

The presence of the railroad also made Roanoke attractive to manufacturers. American Viscose opened a large rayon plant in Southeast Roanoke in October 1917.[35] This plant closed in 1958, leaving 5,000 workers unemployed.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 42.9 square miles (111.1 km2), of which 42.5 square miles (110.1 km2) is land and 0.3 square miles (0.8 km2) (0.8%) is water.[36]

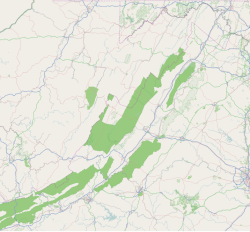

Roanoke is located in the valley and ridge province of Virginia immediately west of the Blue Ridge Mountains and east of the Allegheny Mountains.

Within the city limits is Mill Mountain, which stands detached from surrounding ranges. Its summit features the Roanoke Star, Mill Mountain Zoo, the Discovery Center interpretive building, and an overlook of the Roanoke Valley. The Appalachian Trail runs through the northern section of Roanoke County several miles north of the city, while the Blue Ridge Parkway runs just to the south of the city. Carvins Cove, the second-largest municipal park in America at 12,700-acre (51 km2), lies in northeast Roanoke County and southwest Botetourt County.[37] Smith Mountain Lake is several miles southeast of the city. The Jefferson National Forest is nearby. Roanokers and visitors to the area enjoy hiking, mountain biking, cross-country running, canoeing, kayaking, fly fishing and other outdoor pursuits.

The city is located in the North Fork of Roanoke winemaking region. The "North Fork of Roanoke" appellation is a designated American Viticultural Area, recognizing the unique grape growing conditions present in the area. Valhalla Vineyards is located just outside the city limits of Roanoke.

The Roanoke River flows through the city of Roanoke. Some stretches of the river flow through parks and natural settings, while others flow through industrial areas. Several tributaries join the river in the city, most notably Peters Creek, Tinker Creek and Mud Lick Creek.

Neighborhoods

Within its boundaries, Roanoke is divided into 49 individually defined neighborhoods.

Climate

Though located along the Blue Ridge Mountains at elevations exceeding 900 ft (270 m), Roanoke lies in the humid subtropical climate zone (Köppen Cfa), with four distinct, but generally mild, seasons; it is located in USDA hardiness zone 7b, with the suburbs falling in zone 7a.[38] Extremes in temperature have ranged from 105 °F (41 °C) as recently as August 21, 1983, down to −12 °F (−24 °C) on December 30, 1917, though neither 100 °F (38 °C) nor 0 °F (−18 °C) is reached in most years; the most recent occurrence of each is July 8, 2012 and February 20, 2015.[39] More typically, the area records an average of 6.1 days where the temperature stays at or below freezing and 30.5 days with 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs annually.[39][40] The normal monthly mean temperature ranges from 37.9 °F (3.3 °C) in January to 77.8 °F (25.4 °C) in July.[39][40]

Based on the 1991−2020 period, the city averages 14.8 inches (38 cm) of snow per winter.[40] Roanoke experienced something of a snow drought in the 2000s until December 2009 when 17 inches (43 cm) of snow fell on Roanoke in a single storm.[41] Winter snowfall has ranged from trace amounts in 1918–19 and 1919–20 to 62.7 inches (159 cm) in 1959–60;[39] unofficially, the largest single storm dumped approximately three feet (0.9 m) from December 16−18, 1890.[42]

Flooding is the primary weather-related hazard faced by Roanoke. Heavy rains, most frequently from remnants of a hurricane, drain from surrounding areas to the narrow Roanoke Valley. The most recent significant flood was in the fall of 2004, caused by the remains of Hurricane Ivan. The most severe[43] flooding in the city's history occurred on November 4, 1985, when heavy storms from the remnants of Hurricane Juan stalled over the area. Ten people drowned in the Roanoke Valley and others were saved by rescue personnel.

Many residents complain that they are prone to allergies because of pollen from trees in the surrounding mountains. Most famously, the family of Wayne Newton moved from Roanoke to the dry climate of Phoenix, Arizona, because of his childhood asthma and allergies.[44] However, there have not been clinical studies to establish that these conditions are more prevalent in Roanoke than in other cities with similar vegetation and climate.

| Climate data for Roanoke–Blacksburg Regional Airport, Virginia (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1912–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) |

84 (29) |

90 (32) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

99 (37) |

83 (28) |

80 (27) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 67.2 (19.6) |

70.3 (21.3) |

78.5 (25.8) |

85.7 (29.8) |

89.5 (31.9) |

93.6 (34.2) |

95.8 (35.4) |

94.5 (34.7) |

91.2 (32.9) |

84.6 (29.2) |

76.0 (24.4) |

68.3 (20.2) |

96.9 (36.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 47.1 (8.4) |

50.8 (10.4) |

59.0 (15.0) |

69.7 (20.9) |

77.2 (25.1) |

84.4 (29.1) |

88.1 (31.2) |

86.5 (30.3) |

80.0 (26.7) |

70.1 (21.2) |

59.0 (15.0) |

50.0 (10.0) |

68.5 (20.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 37.9 (3.3) |

40.8 (4.9) |

48.3 (9.1) |

58.0 (14.4) |

66.1 (18.9) |

73.8 (23.2) |

77.8 (25.4) |

76.2 (24.6) |

69.6 (20.9) |

58.9 (14.9) |

48.4 (9.1) |

40.9 (4.9) |

58.1 (14.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 28.7 (−1.8) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

37.6 (3.1) |

46.3 (7.9) |

55.0 (12.8) |

63.2 (17.3) |

67.4 (19.7) |

66.0 (18.9) |

59.1 (15.1) |

47.8 (8.8) |

37.7 (3.2) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

47.6 (8.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 11.0 (−11.7) |

15.8 (−9.0) |

21.3 (−5.9) |

31.5 (−0.3) |

40.3 (4.6) |

51.7 (10.9) |

57.6 (14.2) |

55.6 (13.1) |

45.1 (7.3) |

32.0 (0.0) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

16.9 (−8.4) |

9.0 (−12.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −11 (−24) |

−1 (−18) |

9 (−13) |

15 (−9) |

30 (−1) |

36 (2) |

47 (8) |

42 (6) |

32 (0) |

22 (−6) |

8 (−13) |

−12 (−24) |

−12 (−24) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.17 (81) |

2.89 (73) |

3.51 (89) |

3.49 (89) |

4.31 (109) |

4.66 (118) |

4.28 (109) |

3.37 (86) |

4.06 (103) |

2.96 (75) |

3.04 (77) |

3.08 (78) |

42.82 (1,088) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.3 (11) |

4.8 (12) |

2.3 (5.8) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

3.2 (8.1) |

14.8 (38) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.5 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 10.7 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 11.7 | 9.7 | 9.0 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 9.2 | 120.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 7.1 |

| Source: NOAA[39][40] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 669 | — | |

| 1890 | 16,159 | 2,315.4% | |

| 1900 | 21,495 | 33.0% | |

| 1910 | 34,874 | 62.2% | |

| 1920 | 50,842 | 45.8% | |

| 1930 | 69,206 | 36.1% | |

| 1940 | 69,287 | 0.1% | |

| 1950 | 91,921 | 32.7% | |

| 1960 | 97,110 | 5.6% | |

| 1970 | 92,115 | −5.1% | |

| 1980 | 100,220 | 8.8% | |

| 1990 | 96,397 | −3.8% | |

| 2000 | 94,911 | −1.5% | |

| 2010 | 97,032 | 2.2% | |

| 2020 | 100,011 | 3.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[45] 1790-1960[46] 1900-1990[47] 1990-2000[48] 2010-2012[6] | |||

At the 2000 census,[49] there were 94,911 people, 42,003 households and 24,235 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,213.2 per square mile (854.6/km2). There were 45,257 housing units at an average density of 1,055.3 per square mile (407.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 69.38% White, 26.74% African American, 0.20% Native American, 1.15% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.72% from other races, and 1.78% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.48% of the population.

There were 42,003 households, of which 25.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.1% were married couples living together, 16.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.3% were non-families. 35.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.20 and the average family size was 2.86.

22.6% of the population were under the age of 18, 8.2% from 18 to 24, 30.5% from 25 to 44, 22.3% from 45 to 64, and 16.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.3 males.

The median household income was $30,719 and the median family income was $37,826. Males had a median income of $28,465 and females $21,591. The per capita income was $18,468. About 12.9% of families and 15.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.4% of those under age 18 and 11.3% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2009) |

Roanoke's economy developed around the Norfolk and Western Railroad, with a strong emphasis on manufacturing. Roanoke's economic history also includes Sun Belt characteristics as it was once a center for the garment industry. Surrounding areas have relied on traditional industries of the rural South such as textiles and furniture manufacturing, which have lost jobs to offshore outsourcing. Despite Virginia's being a right to work state, unions have traditionally represented workers at many large employers in the Roanoke area and southwest Virginia.[citation needed]

Roanoke was formerly the headquarters of Norfolk and Western Railway until its merger with the Southern Railway created the Norfolk Southern Railway in 1982. Norfolk Southern continues to operate maintenance facilities and a rail yard in Roanoke but moved its marketing department out and closed its downtown office building in 2015.[50] Wachovia Bank, then known as First Union, acquired Roanoke-based Dominion Bank in 1993 and maintains an operations and customer service center in Roanoke. Other firms have been acquired by companies headquartered elsewhere, including such as Roanoke Electric Steel and architectural and engineering firm Hayes, Seay, Mattern and Mattern, (HSMM) which has been acquired by the multi-national conglomerate AECOM. Roanoke's rates of economic and population growth have been less than the state and national averages since the 1960s. The immediate Roanoke area has a low unemployment rate, but a brain drain of workers unable to find satisfactory employment and underemployment are sometimes cited as explanations.[51]

The City of Roanoke has created initiatives to address the brain drain of the region such as a database to match job seekers who wish to reside in the Roanoke area with employers looking for candidates. Additionally, a career and lifestyle fair has been held shortly after Christmas in recent years to show the professional and social opportunities in the area to those visiting family for the holidays. Also, organizations of young professionals such as Valley Forward and Newva Connects have emerged.[citation needed]

Roanoke's economy has areas of strength. The city is the health care and retail hub of a large area, driving the expansion of Carilion Clinic and Valley View Mall. Advance Auto Parts is headquartered in Roanoke and has expanded through the acquisition of other chains to become one of the largest auto parts retailers in the country. Norfolk Southern remains a major employer. FreightCar America hired several hundred persons to assemble rail cars in shops leased from Norfolk Southern and has closed a plant in Johnstown, Pennsylvania in part because of the lower costs for the Roanoke facility. Recently though, the company laid off its Roanoke employees and said it plans to temporarily close the plant.[52] The corporate offices of Virginia Transformer Corporation and utility company RGC Resources are situated in this city. General Electric and TMEIC manufacture large drive systems for electrical generation stations and factories at their joint facility in Salem. Elbit Systems of America manufactures night vision goggles at its plant in Roanoke County, and some of its former employees have started other firms such as Optical Cable Corporation. The proximity of automotive assembly plants in the South has attracted manufacturers including Dynax, Koyo, Metalsa and Yokohama, formerly Mohawk Tire. Roanoke's location allows for delivery within one day to most markets in the southeast, northeast, mid-atlantic, and Ohio Valley, which has made it a distribution center for such companies as Orvis, Elizabeth Arden, and Hanover Direct. United Parcel Service (UPS) maintains a major facility at the Roanoke Regional Airport. While the city of Roanoke has lost population, suburbs in Roanoke County, southern Botetourt County, and areas of Bedford County and Franklin County near Smith Mountain Lake have grown.[citation needed]

Kroger operates its Mid-Atlantic regional offices at 3631 Peter's Creek Road NW in Roanoke.[53]

Top employers

According to Roanoke's 2011 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[54] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital | 1,000+ |

| 2 | Roanoke City Public Schools | 1,000+ |

| 3 | City of Roanoke | 1,000+ |

| 4 | Carilion Professional Service | 1,000+ |

| 5 | United Parcel Service | 500 to 999 |

| 6 | Healthmarc | 500 to 999 |

| 7 | Walmart | 500 to 999 |

| 8 | Virginia Western Community College | 500 to 999 |

| 9 | Anthem, member of Blue Cross Blue Shield Association | 500 to 999 |

| 10 | United States Postal Service | 500 to 999 |

Arts and culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

EventZone was created in 2003 by the merger of various existing event organizers. EventZone is charged with assisting in the creation of new festivals and activities in the downtown Roanoke "event zone," defined as bounded by Williamson Road, 6th Street, SW, the Roanoke Civic Center and Rivers Edge Park.[55]

Roanoke's festivals and cultural events include the Chili Cook-Off,[56] Festival in the Park, Local Colors Festival,[57][58] Henry Street Festival, Hispanic Heritage Month Celebration, Big Lick Blues Festival, Strawberry Festival, and the large red, white, and blue illuminated Mill Mountain Star (formerly illuminated in red following drunk driving fatalities in the Roanoke Valley; temporarily illuminated in white on April 22, 2007, in remembrance of the Virginia Tech Massacre of April 16, 2007) on Mill Mountain, which is visible from many points in the city and surrounding valley.

Museums

Center in the Square was opened in downtown Roanoke on December 9, 1983, near the city market as part of the city's downtown revitalization effort. The Center, a converted warehouse, houses the History Museum of Western Virginia, which contains exhibits and artifacts related to the area's history and has a library of materials available to scholars and the public. The Center also houses the Science Museum of Western Virginia and the Hopkins Planetarium. The Science Museum maintains a permanent installation of neon sign art featuring the work of local Mark Jamison, the subject of Slash Coleman's PBS special "The Neon Man and Me".[59]

Formerly housed in Center in the Square, the Taubman Museum of Art has now vacated the Center and opened a new facility at 110 Salem Avenue SE. The art museum features 19th and 20th century American art, contemporary and modern art, decorative arts, and works on paper, and presents exhibitions of both regional and national significance. The new 75,000-square-foot (7,000 m2) facility was designed by Los Angeles-based architect Randall Stout, who earlier in his career worked under Frank Gehry. The new space opened on November 8, 2008. The facility's design sparked debate in the community between those who feel it is a bold, refreshing addition to Roanoke and those who feel its unusual, irregular design featuring sharp angles contrasts too strongly with the existing buildings. Some are also concerned about the facility's cost at a time when many Roanoke area artistic organizations face financial challenges. The Taubman Family, which established Advance Auto Parts contributed $15.2 million to the project. As a result, the museum was renamed The Taubman Museum of Art.

The Virginia Museum of Transportation houses many locomotives that were built in Roanoke, including the Norfolk and Western J class#611 and Norfolk & Western 1218 steam engines, and other locomotives and rolling stock. The museum also houses exhibits covering aviation, automobiles and buses.

Roanoke's landmark former passenger rail station hosts the O. Winston Link Museum dedicated to the late steam-era railroad photography of O. Winston Link since 2004.

The Harrison Museum of African-American Culture is dedicated to the history and culture of Roanoke's African-American community and is currently located at a former school in the Gainsboro section of Roanoke. Gainsboro, originally Gainesborough for founder Major Kemp Gaines, was originally a separate community that petitioned for township status in 1835.[60] The Harrison Museum will move to Center in the Square after the Center's remodeling is completed.

Arts

Berglund Center auditorium and theatre, now known as the Roanoke Performing Arts Theatre, has hosted concerts, touring Broadway theatre performances, and the Miss Virginia pageant. The city's first permanent artwork funded by the Percent for Art ordinance stands before the theater. Dedicated in 2008, the 30-foot (9.1 m) stainless steel sculpture, "In My Hands", is one of more than 100 works in the city's public art catalogue.

The Shaftman Performance Hall, which opened in May 2001 and is located at the Jefferson Center, hosts a concerts, performances, entertainment events, and lectures. The Jefferson Center—formerly Jefferson High School—also houses offices and display spaces for cultural organizations.

In 2006, the former Dumas Hotel was reopened as the Dumas Center for Artistic and Cultural Development. The hotel is located on a segment of First Street NW commonly known as Henry Street. Located across the railroad tracks from the center of downtown Roanoke, Henry Street served as the commercial and cultural center of Roanoke's African American community prior to desegregation. The Dumas Hotel hosted such guests as Louis Armstrong, Ethel Waters, Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Nat King Cole when they performed in Roanoke. The renovated Dumas Center houses an auditorium with more than 180 seats, the Downtown Music Lab: a recording studio and music education center for teens, the Dumas Drama Guild and the offices of Opera Roanoke.[citation needed]

Virginia's Theater City

Roanoke Children's Theatre is Roanoke's professional children's theatre. It can be found within the new Taubman Museum of Art in downtown Roanoke. The theatre delivers four shows a year that are geared towards a family audience. The theatre extends their programming in various arts outreach programs throughout the valley and surrounding areas.

Mill Mountain Theatre, a regional theatre, is located on the first floor of Center in the Square. As the name implies, the theatre was originally located on Mill Mountain from 1964 until 1976 when its original facility was destroyed by fire. The theatre has both a main stage for mainstream performances and a smaller black box theatre called Waldron Stage which hosts both newer and more experimental plays along with other live events.

The Grandin Theatre in the Grandin Village of Southwest Roanoke regularly screens art house films, family features, and mainstream movies. The Grandin Theatre was the home of Mill Mountain Theatre from 1976 until 1983.

Virginia Western Theatre has performances in Whitman Auditorium at Virginia Western Community College, and has been performing original and well known theatrical productions since 1968.

Roanoke has also been home to the Showtimers Community Theatre[61] since 1951. Showtimers was formed in the summer of 1950, by a group of people who wanted to present a summer season of amateur productions. Over the years, Showtimers has produced over 300 different shows, from standard, classic theatre pieces to the modern and avant-garde; from comedies designed solely to entertain to serious 'think pieces' on social issues; from small, intimate musicals to large shows made famous on Broadway. Showtimers presents six shows per year.

The Star City Playhouse is well known in Roanoke. "The owners have over 50 years of combined experience working in and around theater on Broadway in New York and maintain an impressive array of costumes and extensive set pieces that have been donated over the years through Marlow's contacts from New York."[62]

Music

Opera Roanoke was founded in 1976 as the Southwest Virginia Opera Society, Opera Roanoke has collaborated with the finest talent in our region, across the state and from cultural centers around the nation. Under the direction of Victoria Bond, Craig Fields, Steven White and Scott Williamson, Opera Roanoke has maintained a reputation for presenting outstanding productions featuring some of the finest singers in the opera world. Metropolitan Opera stars Eleanor Steber and Irene Dalis were among the company's earliest artistic advisors. Although they did not perform, they mentored many young artists in the company's fledgling years as a community organization.[citation needed]

The Roanoke Symphony Orchestra (RSO) was established in 1952. It has special youth and student activities. The Roanoke Youth Symphony has three ensembles: The Roanoke Youth Symphony Orchestra (RYSO); the String Ensemble and the Flute Ensemble. The Roanoke Symphony Chorus was established in 1999 under the direction of Dr. John Hugo. There was a previous organization called the Roanoke Symphony Orchestra, mentioned in the Roanoke Times in February 1942: "Something unique in theatrical circles of the nation is the Civic Theatre of Roanoke, formed from five organizations — Gilbert and Sullivan Light Opera company, the Academy Players, the Civic Chorus, the Community's Children's Theatre and the Roanoke Symphony Orchestra — for the purpose of the better production of entirely local plays and concerts."[citation needed]

Landmarks and points of interest

- Blue Ridge Parkway

- Grandin Village

- Historical Fire Station#1

- Hollins University

- Hotel Roanoke[63]

- Mill Mountain Zoo

- O. Winston Link Museum

- Roanoke Star

- St. Andrew's Roman Catholic Church, State and National Landmark

- Taubman Museum of Art

- Texas Tavern restaurant

- Virginia's Explore Park

Festivals

Roanoke and surrounding communities host the annual Commonwealth Games of Virginia, an Olympic-style amateur sports festival. Beginning in 2010, the Blue Ridge Marathon on the Parkway is scheduled to be held in the city.[64]

Sports

Professional

The 1971–1972 Virginia Squires of the ABA were the only major league sports team to regularly play home games in Roanoke. During the 1971–1972 season, the Squires split home games between Richmond, Norfolk, Hampton Roads and Roanoke.[65] Julius Erving played his professional rookie season with the Squires in 1971–1972.

Minor league baseball has been more successful in building and maintaining a fan base than have the Roanoke Valley's other minor league sports teams. In the 1940s and early 1950s, Roanoke was home to a class B farm team of the Boston Red Sox. Since 1955, neighboring Salem has hosted the local minor league baseball team, currently the Salem Red Sox of the high Class A Carolina League. The team had previously been affiliated with the Houston Astros and Colorado Rockies and known as the Avalanche until becoming an affiliate of the Boston Red Sox, whose ownership group purchased the Avalanche in 2007, for the 2009 season.

Minor league hockey has a history in the Roanoke Valley dating to the 1960s. It reached a zenith of popularity in the mid- to late-1990s with the Roanoke Express of the ECHL. The team's attendance declined due to a lack of post-season success and management turmoil. The Express folded after the 2003–04 season.

The 2005–06 revival by the UHL's Roanoke Valley Vipers failed after one season. The team had a losing record and the midwestern-based league was unable to rekindle the interest of the local fanbase. The team was formed to provide a travel partner for a UHL franchise in Richmond which also folded after the 2005–06 season.

In 2016, professional ice hockey returned to Roanoke after ten years when the Roanoke Rail Yard Dawgs of the Southern Professional Hockey League began play.

The Roanoke Dazzle of the National Basketball Development League (NBDL) and the Roanoke Steam of the af2 (arena football) folded after never developing consistent followings. The Dazzle's attendance was similar to other inaugural franchises in the league. It was one of the last two teams to remain in its original city. Over the years, Roanoke has also had teams in soccer and men's and women's semi-professional football.

College

For a number of years, Roanoke, with Richmond and Norfolk, was one of the nominally neutral sites for the annual basketball game between the Virginia Cavaliers and Virginia Tech Hokies. During most of the 1970s and 1990s, the University of Virginia dominated the rivalry and as such tended to have significantly greater fan representation, despite Roanoke's closer proximity to Virginia Tech's home in Blacksburg. In the late 1990s, the schools started holding these games in their own campus facilities.

Roanoke served as the home for the Big South Conference Men's Basketball Tournament and Women's Basketball Tournament in 2001 and 2002.

The Virginia Tech Hokies ice hockey team has used the Roanoke Civic Center as its regular season home venue, from 2006 to the present season.[66] In 2010, the Roanoke College ice hockey team began using the Roanoke Civic Center as its home venue as well.[67]

From the 1940s to the late 1960s, Roanoke's Victory Stadium hosted an annual Thanksgiving Day game between Virginia Tech and the Virginia Military Institute and other high-profile college football games. From 1946 to 1950, Victory Stadium also hosted the South's Oldest Rivalry between the University of Virginia and the University of North Carolina.

Parks and recreation

The Roanoke Valley Chess Club was formed in 1947 in Roanoke, and is the oldest continuing chess club in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The club has served to bring and sustain chess activities to the region, and holds regular events. These events include United States Chess Federation Grand Prix tournaments. The club also holds volunteer annual outreach events during Roanoke's Festival in the Park, Grandin Court Block Party, Tons of Fun, and more.

Government

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 36.0% 15,607 | 61.8% 26,773 | 2.2% 943 |

| 2016 | 37.5% 14,789 | 56.5% 22,286 | 6.1% 2,391 |

| 2012 | 37.3% 14,991 | 60.1% 24,134 | 2.6% 1,030 |

| 2008 | 37.8% 15,394 | 61.2% 24,934 | 1.1% 444 |

| 2004 | 46.3% 16,661 | 52.4% 18,862 | 1.3% 477 |

| 2000 | 43.8% 14,630 | 53.6% 17,920 | 2.7% 892 |

| 1996 | 38.4% 12,283 | 54.0% 17,282 | 7.7% 2,451 |

| 1992 | 38.2% 13,443 | 50.4% 17,724 | 11.4% 4,014 |

| 1988 | 46.9% 15,389 | 52.4% 17,185 | 0.7% 239 |

| 1984 | 52.1% 19,008 | 47.4% 17,300 | 0.5% 184 |

| 1980 | 43.4% 15,164 | 51.9% 18,139 | 4.7% 1,643 |

| 1976 | 41.0% 14,738 | 57.6% 20,696 | 1.4% 515 |

| 1972 | 64.7% 18,541 | 33.1% 9,498 | 2.2% 632 |

| 1968 | 51.2% 15,368 | 30.9% 9,281 | 17.9% 5,359 |

| 1964 | 46.2% 13,164 | 53.7% 15,314 | 0.1% 18 |

| 1960 | 62.3% 15,229 | 37.5% 9,175 | 0.2% 49 |

| 1956 | 69.4% 16,708 | 28.0% 6,751 | 2.6% 623 |

| 1952 | 66.0% 15,673 | 33.9% 8,042 | 0.1% 32 |

| 1948 | 49.6% 6,542 | 40.5% 5,343 | 10.0% 1,315 |

| 1944 | 40.9% 5,095 | 58.8% 7,322 | 0.3% 34 |

| 1940 | 33.7% 3,553 | 65.9% 6,942 | 0.5% 47 |

| 1936 | 32.0% 3,363 | 67.5% 7,087 | 0.5% 54 |

| 1932 | 33.5% 3,195 | 65.2% 6,215 | 1.4% 130 |

| 1928 | 61.7% 6,471 | 38.3% 4,018 | |

| 1924 | 27.2% 1,747 | 61.1% 3,930 | 11.8% 758 |

| 1920 | 32.6% 2,329 | 66.0% 4,715 | 1.4% 100 |

| 1916 | 20.7% 610 | 76.1% 2,246 | 3.2% 94 |

| 1912 | 9.8% 268 | 69.7% 1,913 | 20.5% 562 |

Roanoke has a weak mayor-city manager form of government. The city manager is responsible for the day-to-day operation of the city's government and has the authority to hire and fire city employees. The mayor has little, if any, executive authority and essentially is the "first among equals" on the Roanoke City Council. The mayor, however, has a bully pulpit as Roanoke media frequently cover the mayor's appearances and statements. The current mayor of Roanoke is Sherman Lea and the current city manager is Robert S. Cowell. The city council has six members, not counting the mayor, all of whom are elected on an at-large basis. A proposal for a ward-based council, in which the mayor and vice mayor would continue to be elected at-large, was rejected by Roanoke voters in 1997, but ward system advocates still contend that the at-large system results in a disproportionate number of council members coming from affluent neighborhoods and that electing some or all council members on a ward basis would result in a more equal representation of all areas of the city. The four-year terms of city council members are staggered, so there are biennial elections. The candidate who receives the most votes is designated the vice mayor for the following two years.

Independent candidate David A. Bowers, a former Democrat, defeated incumbent Democrat Nelson Harris for Mayor in the May 2008 election with 53% of the vote. In both the 2000 election, Republican Ralph K. Smith and in the 2004 election Nelson Harris won with less than 40% of the vote in competitive three-way races.

In the May 2008 council elections, Democrats Court Rosen, Anita Price, and Sherman Lea defeated a slate of loosely allied independent city council candidates including incumbent Brian Wishneff. In the May 2006 council elections, a slate of three former Democrats running on an independent slate backed by Harris defeated the candidates of the Democratic and Republican parties. This election ended the city's long-running debate about the fate of Victory Stadium.

On June 27, 2016, Sherman P. Lea, Sr. took the office of mayor.[69]

Roanoke is represented by two members of the Virginia House of Delegates, Sam Rasoul (D-11th) and Chris Head (R-17th), and one member of the Virginia Senate, John Edwards (D-21st). Former Roanoke mayor Ralph Smith won the 2007 election in the neighboring 22nd Senate district after defeating incumbent Brandon Bell for the Republican nomination in the primary election and Democrat Michael Breiner in the general election.

The City of Roanoke lies within Virginia's 6th congressional district, which also includes Lynchburg and much of the Shenandoah Valley and is represented by Republican Ben Cline. Virginia's 9th congressional district, represented by Republican Morgan Griffith of neighboring Salem, has traditionally covered southwest Virginia but has expanded into parts of Salem, Roanoke County and counties to the north of Roanoke to make up for population losses in the rest of the district. Republican Bob Good represents much of the area to south and east of Roanoke, including nearby Franklin County, in Virginia's 5th congressional district which also stretches north to Charlottesville.

Roanoke is one of the few Democratic pockets in heavily Republican southwestern Virginia. It has supported the Democratic Party nominee in every election since 1988, and in all but one election since 1976. In statewide elections, Roanoke is often one of the few areas west of Charlottesville to vote Democratic.

Education

The local public school division is Roanoke City Public Schools. The two general enrollment public high schools in Roanoke City are Patrick Henry High School, located in the Raleigh Court area, and William Fleming High School, located in Northwest Roanoke. The six public middle schools in Roanoke City are Woodrow Wilson, James Madison Middle School and John P. Fishwick[70] that feed into Patrick Henry High School, and Lucy Addison, William Ruffner and James Breckinridge, that feed into William Fleming High School.[71] The Noel C. Taylor learning academy is a combined middle and high school that serves students with individual educational needs.[citation needed]

Private non-parochial schools in Roanoke City include Community High School, that provides classes from ninth to 12th grade, and New Vista Montessori, that provides classes from third to ninth grade.[72] Private non-parochial schools outside of Roanoke City, but in the Roanoke Metropolitan Area, include North Cross School,[73] which provides education from pre-kindergarten through the 12th grade.[74]

Private parochial schools in Roanoke City include North Cross and Roanoke Catholic,[75] that provide classes from kindergarten to twelfth grade, and Roanoke Adventist Preparatory, that provides classes from kindergarten to eighth grade.[76] Private parochial schools outside of Roanoke City, but in the Roanoke Metropolitan Area, include Roanoke Valley Christian Schools, Faith Christian School, Mineral Springs Christian School, Parkway Christian Academy and Life Academy, all in Roanoke County.

Two four-year private institutions are situated in neighboring localities – Roanoke College in the city of Salem, and Hollins University in Roanoke County. Virginia Tech and Radford University's main campuses are located the nearby New River Valley, but Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and Research Institute opened in 2007 and Virginia Tech also operates a satellite campus for higher education in downtown Roanoke. The medical school is in cooperation with Carilion Clinic, the regional nonprofit health care organization based in Roanoke.[77] Virginia Western Community College is located in the city of Roanoke, as is the Jefferson College of Health Sciences.

Media

The city's daily newspaper, The Roanoke Times, has been published since 1886. Weekday circulation averages a little over 90,000 with Sunday circulation around 103,000. In 2002, it was designated the best-read daily newspaper in the country by the 2002 Scarborough Report. Of 162 newspapers in top US metropolitan areas, The Roanoke Times ranked first in the percentage of adults who read their daily newspaper. It ranked first again in 2006.[78] The Roanoke Times established a web site in 1995 and has developed a web portal at Roanoke.com.

The Roanoke Times formerly published Blue Ridge Business Journal which served the business community in Roanoke and the surrounding region. However, it ceased freestanding publication in 2010[79] and was folded into the newspaper's Sunday Business Publication as The Ticker. Valley Business Front is a monthly publication that targets the business community in the region. The weekly Roanoke Tribune was founded in 1939 by Fleming Alexander and covers the city's African-American community. Main Street Newspapers publishes weekly newspapers for surrounding communities such as Salem, Vinton, southwest Roanoke County and Botetourt County. Play by Play is a monthly publication dedicated to local and regional sports.

The Roanoke Star-Sentinel is a weekly newspaper which covers the city of Roanoke. The South Roanoke Circle is an independent monthly newspaper for the neighborhood of South Roanoke.

The Roanoker is the area's bi-monthly lifestyle magazine and is published by Leisure Publishing, which also publishes the bi-monthly Blue Ridge Country magazine.

Broadcast

Television

Roanoke and Lynchburg are grouped in the same television market, which currently ranks #67 in the United States with 440,398 households. There are affiliates for all networks as well as independent stations. Stations in this market that are located in Roanoke include Fox affiliate WFXR Fox 21/27 in Roanoke, PBS affiliate WBRA-15 in Roanoke, and ION Television affiliate WPXR-38 in Roanoke.[citation needed]

Radio

The Roanoke-Lynchburg radio market has a population of 449,800 and is ranked #115 in the United States as of 2020.[80]

| FM stations located in Roanoke | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Call Letters | Frequency | Format | Location | Owner |

| WVTF | 89.1 | Public Radio | Roanoke | Virginia Tech Foundation |

| WRXT | 90.3 | Christian Contemporary | Roanoke | Positive Alternative Radio |

| WXLK | 92.3 | Top-40 Radio | Roanoke | Wheeler Broadcasting |

| WSLC | 94.9 | Country | Roanoke | Wheeler Broadcasting |

| WROV | 96.3 | Classic Rock | Martinsville/Roanoke | iHeart Media |

| WSLQ | 99.1 | Adult Contemporary | Roanoke | Wheeler Broadcasting |

| WLRX | 106.1 | Contemporary Christian | Roanoke | Educational Media Foundation |

| AM stations located in Roanoke | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Call Letters | Frequency | Format | Owner | |

| WPLY | 610 | Sports | Wheeler Broadcasting | |

| WFJX | 910 | News/Talk | Perception Media | |

| WFIR | 960 | News/talk | Wheeler Broadcasting | |

| WGMN | 1240 | News/talk | 3 Daughters Media | |

| WRTZ | 1410 | Oldies/classic hits | Metromark Media | |

Infrastructure

Transportation

Roads

Interstate 581 is the primary north-south roadway through the city. It is also the only interstate highway as Interstate 81 passes north of the city limits. Interstate 581 is a concurrency with U.S. Route 220, which continues as the Roy L. Webber Expressway from downtown Roanoke, where the I-581 designation ends, south to State Route 419. Route 220 connects Roanoke to Martinsville, Virginia and Greensboro, North Carolina. The proposed Interstate 73 would generally parallel Route 220 between Roanoke and Greensboro and would likely be a concurrency with I-581 through the city. The primary east-west roadway is U.S. Route 460, named Melrose Avenue and Orange Avenue. Route 460 connects Roanoke to Lynchburg. U.S. Route 11 passes through the city, primarily as Brandon Avenue and Williamson Road, which was a center of automotive-based commercial development after World War II. Other major roads include U.S. Route 221, State Route 117 (known as Peters Creek Road) and State Route 101 (known as Hershberger Road). The Blue Ridge Parkway also briefly runs adjacent to the city border.[81]

Roanoke is divided into four quadrants: Northwest (NW), Northeast (NE), Southwest (SW) and Southeast (SE). The mailing address for locations in Roanoke includes the two letter quadrant abbreviation after the street name. For example, the Center in the Square[82] complex in downtown Roanoke has the address "1 Market Square SE".

Airports

The Roanoke-Blacksburg Regional Airport is located in the northern part of the city and is the primary passenger and cargo airport for Southwest Virginia.[83]

Rail

The city was known for its rail history. Into the 1960s the Norfolk and Western and Southern Railway ran three trains a day toward New York City; the trains went to different destinations to the west and south: Memphis, Nashville and New Orleans. From October 1, 1979, to October 31, 2017, Roanoke did not have passenger rail service.[84] In August 2013, it was announced that Amtrak service as part of their Northeast Regional would be extended from Lynchburg to Roanoke by 2017. Construction of a platform for this new service began in fall 2016.[85] On October 31, 2017, after nearly 40 years without passenger rail service, Amtrak resumed service to Roanoke.[86] Before passenger rail service resumed, a bus service, the Smart Way Connector, aligned with the Amtrak schedule to connect riders to the Kemper Street Station in Lynchburg.

Roanoke is a major hub in Norfolk Southern's freight rail system. In 2006, the railroad announced plans to construct an intermodal rail yard in the community of Lafayette, Virginia of neighboring Montgomery County; however, opposition by local residents prompted Norfolk Southern to consider other potential sites. In 2007, the former Roanoke mayor David A. Bowers urged Roanoke to offer a site for the yard. Shortly thereafter, neighboring Salem proposed a site in an industrial area of the city. In 2008, Norfolk Southern determined that the Lafayette location was the only practical site. The Commonwealth of Virginia may also upgrade Norfolk Southern's rail line parallel to Interstate 81 from Roanoke through the Shenandoah Valley to encourage more freight to be shipped by rail.

Buses

The Valley Metro bus system serves the city of Roanoke and surrounding areas. Nearly all routes originate or terminate at the Campbell Court bus station in downtown Roanoke, which is also served by Greyhound. Valley Metro also offers bus service to Blacksburg, Christiansburg, Lynchburg and Virginia Tech via the Smart Way and Smart Way Connector services. In addition, several free shuttles connect local colleges to downtown Roanoke. The Ferrum Express runs between Ferrum College in nearby Rocky Mount and downtown Roanoke, while the Hollins Express connects to Hollins University in Roanoke County.

Transportation demand management

Roanoke City is served by RIDE Solutions, a regional transportation demand management agency that provides carpool matching, bicycle advocacy, transit assistance and telework assistance to businesses and citizens in the region.

Notable people

Born in Roanoke:

- Tony Atlas, wrestler

- Ronde Barber, NFL player

- Tiki Barber, NFL player

- Beth A. Brown, NASA astrophysicist

- George E. Bushnell, Michigan Supreme Court justice

- Tai Collins, model and actress

- Henry H. Fowler, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury

- Dorothy Gillespie, artist, sculptor

- Antoinette Hale, painter

- Jim Harrell, professional wrestler

- K. J. Hippensteel, tennis player

- Louis A. Johnson, United States Secretary of Defense

- Danny Karbassiyoon, Arsenal FC soccer player

- Henrietta Lacks, medical patient[87]

- George Lynch, NBA player

- John C. Mather, Astrophysicist and Nobel laureate

- John Alan Maxwell, artist

- Walter Muir, International Master of Correspondence Chess

- John Payne, actor

- Don Pullen, jazz pianist

- Billy Sample, MLB outfielder

- John St. Clair, NFL player

- Curtis Staples, basketball player

- Lee Suggs, NFL player

- Nicholas F. Taubman, former United States Ambassador to Romania

- Lois Weaver, artist, activist, writer, director and Professor of Contemporary Performance at Queen Mary University of London

- Eric Weinrich, NHL defenseman

Raised in Roanoke:

- George Canale, MLB player

- Wayne LaPierre, CEO of the National Rifle Association

- John McAfee, founder of McAfee

- Wayne Newton, singer

- J. J. Redick, NBA player[88]

One-time resident:

- Fleming Alexander, minister, businessman and publisher of the Roanoke Tribune

- Nelson S. Bond, author

- Whitney Cummings, comedian and actress

- Nidal Hasan, shooter in the 2009 Fort Hood shooting

- Oliver Hill, civil rights attorney

- Kermit Hunter, playwright

- Johan Kriek, tennis player

- Samuel W. Martien, Louisiana cotton planter and politician

- Oscar Micheaux, early 20th century filmmaker

- John Forbes Nash, Mathematician and Nobel laureate

- Harry Penn, dentist and civic rights activist

- John Henry Pinkard, businessman, banker and herb doctor

- Curtis Turner, NASCAR legend, pioneer and Hall of Famer

- Bill White, neo-Nazi, American National Socialist Workers' Party Commander

Nicknames

Many businesses and organizations have adopted "Star City" in their names, after the Mill Mountain Star. The older "Magic City"[89] is still used, most prominently by Roanoke's Ford dealership.[90] The city's original name of "Big Lick" is often used in whimsical contexts.

Roanoke's status as the largest city in a mountainous area led to the nickname "Capital of the Blue Ridge".[91]

Sister cities

Roanoke has seven sister cities:[92]

See also

References

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Virginia Birding and Wildlife Trail » Mountain Trail » Star City » Roanoke Water Pollution Control Plant". Dgif.state.va.us. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Roanoke City High Point Trip Report". Cohp.org. November 17, 2000. Archived from the original on October 4, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b "QuickFacts Roanoke city, Virginia". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ "Roanoke Region of Virginia". Roanoke.org. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Roanoke Regional Trade Area". Roanoke.org. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- "Roanoke-Lynchburg DMA Map". newportmedia.com. Retrieved April 11, 2014.[permanent dead link] - ^ "Gainsboro Neighborhood Plan". City of Roanoke. 2003. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Scholl Center for American History and Culture. "Virginia: Individual County Chronologies". Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. Chicago: Newberry Library. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c Dotson 2008.

- ^ a b c "Maps and Formation Information: Roanoke". County and City Records. Library of Virginia. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Federal Writers' Project 1941.

- ^ a b c d Jack and Jacobs 1912.

- ^ a b c d e f Hoffer 1928.

- ^ "Cities of Virginia: Roanoke". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ a b "US Newspaper Directory". Chronicling America. Washington DC: Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ a b "Encyclopedia Virginia". Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Archived from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ a b "Roanoke, Virginia". Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities. Jackson, Mississippi: Goldring / Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ a b "Movie Theaters in Roanoke, VA". CinemaTreasures.org. Los Angeles: Cinema Treasures LLC. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ Kenneth T. Jackson (1992) [1967]. The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915-1930. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 978-1-4617-3005-7.

- ^ Jack Alicoate, ed. (1939), "Standard Broadcasting Stations of the United States: Virginia", Radio Annual, New York: Radio Daily, OCLC 2459636

- ^ Christina Rogers, "Dr Pepper pops to life again", Roanoke.com. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Charles A. Alicoate, ed. (1960), "Television Stations: Virginia", Radio Annual and Television Year Book, New York: Radio Daily Corp., OCLC 10512206

- ^ Vernon N. Kisling, Jr., ed. (2001). "Zoological Gardens of the United States (chronological list)". Zoo and Aquarium History. USA: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-3924-5.

- ^ "About Us". Roanoke: Historical Society of Western Virginia. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ a b "City Council: Council History". City of Roanoke. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ "Virginia". Official Congressional Directory. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1993. hdl:2027/uc1.l0072691827 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ "City Web: Roanoke, VA". Archived from the original on August 16, 2000 – via Internet Archive, Wayback Machine.

- Kevin Hyde; Tamie Hyde (eds.). "United States of America: Virginia". Official City Sites. Utah. OCLC 40169021. Archived from the original on August 24, 2000. - ^ "Roanoke city, Virginia". QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ "Roanoke". Xroads.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on May 21, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Trade Items as Transfer of Money". Lost-colony.com. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Microsoft Word - ROANOKE.DOC" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ [1] [permanent dead link]

- ^ "American Viscose Corp., Marcus Hook, PA". OldChesterPa. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ [2] Archived March 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ United States Department of Agriculture. "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". United States National Arboretum. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Station: Roanoke RGNL AP, VA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ Ballisty, Tim (January 14, 2013). "Snow Totals Adding Up from Blizzard 2009". weather.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ "1890 snowstorm one of biggest events in Roanoke's weather history". www.roanoke.com. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ "What was the worst hurricane to affect Southwest Virginia", Roanoke.com, November 4, 2015

- ^ [3] Archived October 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ "Norfolk Southern to close Roanoke office building, relocate employees". Norfolk Southern. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^ "No mountain retreat". Virginia Business Online. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "FreightCar America to halt production at its second shop in two mont". GLG News. GLG Group. April 16, 2009. Archived from the original on May 25, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us", Kroger. Archived April 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on April 30, 2009.

- ^ "City of Roanoke CAFR" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 29, 2014.

- ^ "Eventzone homepage". eventzone.org. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ McCallum, Annie (June 21, 2014). "Annual Chili cook-off turns up the heat". The Roanoke Times. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ "Local Colors of Western Virginia". Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ Allen, Mike (May 21, 2021). "Arts & Extras: A taste of Southwest Virginia's Local Colors returns to Roanoke". The Roanoke Times. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ Amacker, Walt (November 16, 2008). "'Neon Man and Me' to air on television". Knight-Rider/Tribune Business News.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Gainsboro Neighborhood Plan". Roanokeva.gov. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ""MAGIC CITY" CLASS, COMMUNITY, AND REFORM IN ROANOKE, VIRGINIA, 1882–1912" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009. - ^ "Showtimers Community Theatre - History". October 3, 2018. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018.

- ^ "Star City Playhouse Making Move To Vinton" Archived December 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Roanoke Star, December 20, 2016.

- ^ "The Hotel Roanoke & Conference Center, Curio Collection by Hilton". Hilton.com. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ Jenny Kincaid Boone, "New marathon rising in Roanoke", The Roanoke Times, August 13, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "Virginia Squires". Remember the ABA. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "ROANOKE CIVC CENTER". Archived from the original on February 25, 2007. Retrieved January 19, 2007.

- ^ [4] Archived October 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org.

- ^ "Sherman Lea sworn in as Roanoke's mayor". Go Dan River. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ^ "Stonewall Jackson Middle School renamed after former railroad leader | Education | roanoke.com".

- ^ [5] Archived March 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Private Secular Schools". Roanokeva.gov. Archived from the original on May 21, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "North Cross School - North Cross School". Northcross.org. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ "North Cross School ~ School Mission, Facts & Stats". Northcross.org. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Roanoke Catholic School – Mission Statement". Roanokecatholic.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Private Parochial Schools". Roanokeva.gov. Archived from the original on May 21, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Virginia Tech, Carilion will create joint medical school in Roanoke". Vtnews.vt.edu. Virginia Tech. January 3, 2007. Archived from the original on June 2, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "The Roanoke Times ranks best-read weekday newspaper in the country". Roanoke.com. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on March 14, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Blue Ridge Business Journal to cease publication - Roanoke.com". Archived from the original on September 9, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ "Radio Market Survey Population, Rankings & Information" (PDF). Nielsen. The Nielsen Company. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Parkway in Virginia". Nps.gov. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Center in the Square". Center in the Square. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ "About us – Roanoke–Blacksburg Regional Airport". flyroa.com. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ "Can passenger rail return to Roanoke?". Roanoke.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ Sturgeon, Jeff (May 23, 2016). "Building of Roanoke's Amtrak platform expected to start this fall, state says". Roanoke Times. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ Wickline, Alison. "Roanoke celebrates inaugural Amtrak ride". www.wsls.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ "WHO honors Henrietta Lacks, Roanoke native whose cells served science". WDBJ7.com. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Berman, Mark (September 21, 2021). "Former Cave Spring star J.J. Redick retires from the NBA". Roanoke.com. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ "Accreditation Works No 54". Calea.org. Archived from the original on July 28, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Magic City Ford". Magic City Ford. Archived from the original on August 21, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "The Fairfax: Location". Thefairfaxroanoke.com. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- Joe Kennedy (June 6, 2007). "Tide can turn even for elite of Roanoke". Roanoke.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2009.{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; February 1, 2013 suggested (help) - ^ "Home". Roanoke Valley Sister Cities. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

Bibliography

- Richard Edwards, ed. (1855), "Big Lick", Statistical Gazetteer of the State of Virginia, Richmond

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - F.P. Smith (1891). Synopsis of Roanoke and Her Wonderful Prosperity. W. M. Yager and Co., Real Estate Brokers. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Reports of the City of Roanoke, Virginia, archived from the original on August 25, 2017, retrieved August 25, 2017 circa 1893-

- Picturesque Roanoke. 1902. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 394–395.

- George S. Jack; E.B. Jacobs (1912). History of Roanoke County; History of Roanoke City. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Frank William Hoffer (1928), Public and Private Welfare, Roanoke, Virginia, Roanoke City Planning and Zoning Commissions, archived from the original on August 25, 2017, retrieved August 25, 2017 (Fulltext)

- Federal Writers' Project (1941), "Roanoke", Virginia: a Guide to the Old Dominion, American Guide Series, Oxford University Press, pp. 301–306, ISBN 9780403021956 – via Google Books

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - "Journal of the Roanoke Historical Society", Journal of the Roanoke Valley Historical Society, ISSN 0278-2936 circa 1964-

- Ory Mazar Nergal, ed. (1980), "Roanoke, VA", Encyclopedia of American Cities, New York: E.P. Dutton, OL 4120668M

- Mary Bishop (January 29, 1995), "Street by Street, Block by Block: How Urban Renewal Uprooted Black Roanoke", Roanoke Times, archived from the original on March 17, 2017, retrieved August 25, 2017 – via Roanoke Public Libraries (Fulltext)

- Paul T. Hellmann (2006). "Virginia: Roanoke". Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-135-94859-3.

- Rand Dotson (2008). Roanoke, Virginia, 1882-1912: Magic City of the New South. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-643-8.

External links

- Official website

- The History of the Roanoke Fire Department in progress from the 1880s to present, with current news and links

- Brief history and modern panoramic photos from the Roanoke Civil War Round Table

- "City of Roanoke". County and City Records. Richmond: Library of Virginia.

- Items related to Roanoke, Virginia, various dates (via Digital Public Library of America)