Ferris Bueller's Day Off

| Ferris Bueller's Day Off | |

|---|---|

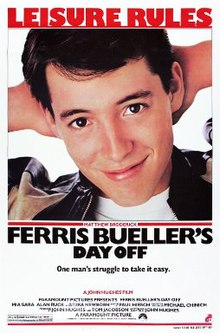

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Hughes |

| Written by | John Hughes |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Tak Fujimoto |

| Edited by | Paul Hirsch |

| Music by | Ira Newborn |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 103 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5 million[1] |

| Box office | $70.7 million[2] |

Ferris Bueller's Day Off is a 1986 American teen comedy film written, co-produced, and directed by John Hughes, co-produced by Tom Jacobson, and starring Matthew Broderick, Mia Sara, and Alan Ruck. It tells the story of a high school slacker who skips school for a day in Chicago and regularly breaks the fourth wall to explain his techniques and inner thoughts.

Hughes wrote the screenplay in less than a week. Filming began in September 1985 and finished in November. Featuring many Chicago landmarks, including the then Sears Tower, Wrigley Field and the Art Institute of Chicago, the film was Hughes's love letter to Chicago: "I really wanted to capture as much of Chicago as I could. Not just in the architecture and landscape, but the spirit."[3]

Released by Paramount Pictures on June 11, 1986, the film became the tenth highest-grossing film of 1986 in the United States, grossing $70 million over a $5 million budget. The movie received acclaim from critics and audiences who praised Broderick's performance, the humor, and the tone.

In 2014, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress, being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[4][5][6]

Plot

In suburban Chicago, the month before graduation, high school senior Ferris Bueller fakes illness to stay home. Throughout the film, Ferris breaks the fourth wall to comment on his friends and give life advice. His parents believe he is ill, though his sister Jeanie does not.

Dean of Students Ed Rooney commits to exposing Ferris's repeat truancy. Ferris convinces his best friend Cameron Frye, legitimately absent due to illness (though Ferris sees through his hypochondria), to help lure Ferris's girlfriend Sloane Peterson from school using her grandmother's supposed demise as pretext. To further the ruse, Ferris borrows Cameron's father's prized 1961 Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder. Cameron is dismayed when Ferris wants to take the car on a day trip in downtown Chicago. Ferris promises they will return it as it was, including preserving the original odometer mileage.

After leaving the car with parking attendants, who promptly go on a joyride, the trio explore the city including the Art Institute of Chicago, Sears Tower, Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and Wrigley Field; their paths occasionally intersect with those of Ferris's father, Tom. Cameron remains worried. Ferris attempts to cheer him up by joining a parade float during the Von Steuben Day parade and spontaneously lip-syncing Wayne Newton's cover of "Danke Schoen", followed by a rendition of the Beatles' cover of "Twist and Shout", which excites the gathered crowds.

Meanwhile, attempting to prove Ferris's truancy, Rooney prowls the Bueller home, getting into several pratfalls. At the same time, Jeanie, frustrated that the entire school blindly supports Ferris, skips class and returns home to confront him. Surprised by Rooney's presence there, she knocks him unconscious. As Jeanie phones the police, Rooney gains consciousness and goes back outside accidentally leaving his wallet behind. When the police arrive, they are unconvinced and arrest Jeanie for making a false report. Waiting for her mother at the police station, she meets a juvenile delinquent friend of Ferris who advises her to worry less about what Ferris does and more about her own life.

Upon collecting the Ferrari and heading home, the friends discover many more miles on the odometer than they realistically could have added themselves. Cameron becomes semi-catatonic from shock, but wakes up after falling into a pool. Ferris is forced to save him, much to Cameron's amusement. Back at Cameron's house, Ferris jacks up the car and runs it in reverse to rewind the odometer. This ploy fails and Cameron snaps, letting out his anger against his overbearing father. Repeatedly kicking the car causes the jack to fail and the car races in reverse through the plate glass window and into the ravine below. Ferris offers to take the blame, but Cameron declines the offer deciding to finally stand up to his father. Meanwhile, Mrs. Bueller arrives at the station, upset about having to forgo an important real estate sale only to find Jeanie kissing the delinquent.

After walking Sloane home, Ferris realizes his parents are due home imminently. As he races on foot through the neighborhood, he is nearly hit by Jeanie who is driving their mother home. Jeanie notices him, and races him home so his mom will catch him, she does this by driving recklessly and arguing with her mother in the car.

Ferris makes it home first, but finds Rooney there. Seeing Ferris through the window and remembering the advice of the delinquent, Jeanie has a change of heart. She thanks Rooney for helping return Ferris home safely after "he tried to walk home from the hospital" and presents Rooney's wallet as proof of his earlier intrusion. As Rooney flees from Ferris's Rottweiler, Ferris rushes back to his bedroom to await his parents who are coming to check in on him. Finding him sweaty and overheated (from his run), they suggest he might want to take tomorrow off as well. As his parents leave, Ferris reminds the audience. "Life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it."

During the end credits, a defeated Rooney heads home and is picked up by a school bus where he is further humiliated by the students.

In the post-credits, a surprised Ferris tells the audience the film is over and to go home.

Cast

- Matthew Broderick as Ferris Bueller

- Mia Sara as Sloane Peterson, Ferris's girlfriend

- Alan Ruck as Cameron Frye, Ferris's best friend

- Jeffrey Jones as Ed Rooney, the Dean of Students

- Jennifer Grey as Jeanie "Shana" Bueller, Ferris's sister

- Cindy Pickett as Katie Bueller, Ferris's mother

- Lyman Ward as Tom Bueller, Ferris's father

- Edie McClurg as Grace, the school secretary

- Charlie Sheen as a boy in the police station who knows Jeanie

- In the original script the character was named Garth Volbeck.

- Ben Stein as Economics teacher

- Del Close as English teacher

- Virginia Capers as Florence Sparrow, a school nurse

- Richard Edson as Garage attendant

- Larry Flash Jenkins as Attendant's co-pilot

- Kristy Swanson as Economics student

- Max Perlich as Economics student

- T. Scott Coffey as Economics student

- Anne Ryan as Shermerites

- Jonathan Schmock as Chez Quis Maitre D'

- Louie Anderson as Flower deliveryman

- Stephanie Blake as Singing nurse

- Dee Dee Rescher as Bus driver

Production

Writing

As he was writing the film in 1985, John Hughes kept track of his progress in a spiral-bound logbook. He noted that the basic storyline was developed on February 25. It was successfully pitched the following day to Paramount Studios chief Ned Tanen. Tanen was intrigued by the concept, but wary that the Writers Guild of America was hours away from picketing the studio.[7] Hughes wrote the screenplay in less than a week.[8] Editor Paul Hirsch explained that Hughes had a trance-like concentration to his script-writing process, working for hours on end, and would later shoot the film on essentially what was his first draft of the script. "The first cut of Ferris Bueller's Day Off ended up at two hours, 45 minutes. The shortening of the script had to come in the cutting room", said Hirsch.[9] "Having the story episodic and taking place in one day...meant the characters were wearing the same clothes. I suspect that Hughes writes his scripts with few, if any costume changes just so he can have that kind of freedom in the editing."[9]

Hughes intended to focus more on the characters rather than the plot. "I know how the movie begins, I know how it ends", said Hughes. "I don't ever know the rest, but that doesn't seem to matter. It's not the events that are important, it's the characters going through the event. Therefore, I make them as full and real as I can. This time around, I wanted to create a character who could handle everyone and everything."[10]

Edward McNally was rumored as the inspiration for the character Ferris Bueller. McNally grew up on the same street as Hughes, had a best friend named "Buehler", and was relentlessly pursued by the school dean over his truancy, which amounted to 27 days absent, compared to Bueller's 9 in the film.[11]

Casting

Hughes said that he had Broderick in mind when he wrote the screenplay, saying Broderick was the only actor he could think of who could pull off the role, calling him clever and charming.[12] "Certain guys would have played Ferris and you would have thought, 'Where's my wallet?'" Hughes said. "I had to have that look; that charm had to come through. Jimmy Stewart could have played Ferris at 15...I needed Matthew."[12] Anthony Michael Hall, who had worked with Hughes on three previous films, was offered the part but turned it down as he was busy with other projects.[13][14] Other actors who were considered for the role included Jim Carrey,[15] John Cusack,[15] Johnny Depp,[16] Tom Cruise, and Michael J. Fox.[17]

Sara surprised Hughes when she auditioned for the role of Sloane Peterson. "It was funny," she said. "He didn't know how old I was and said he wanted an older girl to play the 17-year-old. He said it would take someone older to give her the kind of dignity she needed. He almost fell out of his chair when I told him I was only 18."[18] Molly Ringwald, who had also wanted to play Sloane, said, "John wouldn't let me do it: he said that the part wasn't big enough for me."[7]

Ruck had auditioned for the Bender role in The Breakfast Club that went to Judd Nelson, but Hughes remembered Ruck and cast him as the 17-year-old Cameron Frye.[19] Hughes based the character of Cameron on a friend of his in high school: "He was sort of a lost person. His family neglected him, so he took that as license to really pamper himself. When he was legitimately sick, he actually felt good, because it was difficult and tiring to have to invent diseases but when he actually had something, he was relaxed."[20] Ruck said the role of Cameron had been offered to Emilio Estevez, who turned it down. "Every time I see Emilio, I want to kiss him", said Ruck. "Thank you!"[7] Ruck, then 29, worried about the age difference. "I was worried that I'd be 10 years out of step, and I wouldn't know anything about what was cool, what was hip, all that junk. But when I was going to high school, I didn't know any of that stuff then, either. So I just thought, well, hell—I'll just be me. The character, he's such a loner that he really wouldn't give a damn about that stuff anyway. He'd feel guilty that he didn't know it, but that's it."[19] Ruck was not surprised to find himself cast young. "No, because, really, when I was 18, I sort of looked 12", he said. "Maybe it's a genetic imbalance."[19]

Ruck and Broderick had previously acted together in the Broadway production of Biloxi Blues. Cameron's "Mr. Peterson" voice was an in-joke imitation of their former director Gene Saks.[7] Ruck felt at ease working with Broderick, often crashing in his trailer. "We didn't have to invent an instant friendship like you often have to do in a movie", said Ruck. "We were friends."[7]

Jones was cast as Rooney based on his role in Amadeus, where he played the emperor; Hughes thought that character's modern equivalent was Rooney.[20] "My part was actually quite small in the script, but what seemed to be the important part to me was that I was the only one who wasn't swept along by Ferris", recalls Jones.[21] "So I was the only one in opposition, which presented a lot of opportunities, some of which weren't even in the script or were expanded on. John was receptive to anything I had to offer, and indeed got ideas along the way himself. So that was fun, working with him."[21] "Hughes told me at the time—and I thought he was just blowing his own horn—he said, 'You are going to be known for this for the rest of your life.' And I thought, 'Sure'... but he was right."[22] To help Jones study for the part, Hughes took him to meet his old vice principal. "This is the guy I want you to pay close attention to," Jones explained to Hughes' biographer Kirk Honeycutt. While meeting him, the VP's coat momentarily flew open revealing a holster and gun attached to the man's belt. This made Jones realize what Hughes had envisioned."The guy was 'Sign up for the Army quick before I kill you!'" Jones exclaimed.[23]

Stein says he got the role of Bueller's Economics teacher through six degrees of separation.[24] "Richard Nixon introduced me to a man named Bill Safire, who's a New York Times columnist. He introduced me to a guy who's an executive at Warner Brothers. He introduced me to a guy who's a casting director. He introduced me to John Hughes. John Hughes and I are among the only Republicans in the picture business, and John Hughes put me in the movie", Stein said.[24] Hughes said that Stein was an easy and early choice for the role of the teacher: "He wasn't a professional actor. He had a flat voice, he looked like a teacher."[20]

Filming

"Chicago is what I am," said Hughes.[3] "A lot of Ferris is sort of my love letter to the city. And the more people who get upset with the fact that I film there, the more I'll make sure that's exactly where I film. It's funny—nobody ever says anything to Woody Allen about always filming in New York. America has this great reverence for New York. I look at it as this decaying horror pit. So let the people in Chicago enjoy Ferris Bueller."[3]

For the film, Hughes got the chance to take a more expansive look at the city he grew up in. "We took a helicopter up the Chicago River. This is the first chance I'd really had to get outside while making a movie. Up to this point, the pictures had been pretty small. I really wanted to capture as much of Chicago as I could, not just the architecture and the landscape, but the spirit."[3] Shooting began in Chicago on September 9, 1985.[25] In late October 1985, the production moved to Los Angeles, and shooting ended on November 22.[26] The Von Steuben Day Parade scene was filmed on September 28. Scenes were filmed at several locations in downtown Chicago and Winnetka (Ferris's home, his mother's real estate office, etc.).[27] Many of the other scenes were filmed in Northbrook, Illinois, including at Glenbrook North High School.[28] The exterior of Ferris's house is located at 4160 Country Club Drive, Long Beach, California,[27] which, at the time of filming, was the childhood home of Judge Thad Balkman.[29]

The modernist house of Cameron Frye is located in Highland Park, Illinois. Known as the Ben Rose House,[30] it was designed by architects A. James Speyer, who designed the main building in 1954, and David Haid, who designed the pavilion in 1974. It was once owned by photographer Ben Rose, who had a car collection in the pavilion. In the film, Cameron's father is portrayed as owning a Ferrari 250 GT California in the same pavilion.[31] According to Lake Forest College art professor Franz Shulze, during the filming of the scene where the Ferrari crashes out of the window, Haid explained to Hughes that he could prevent the car from damaging the rest of the pavilion.[32] Haid fixed connections in the wall and the building remained intact. Haid said to Hughes afterward, "You owe me $25,000", which Hughes paid.[32] In the DVD commentary for the film, Hughes mentions that they had to remove every pane of glass from the house to film the car crash scene, as every pane was weakened by age and had acquired a similar tint, hence replacement panels would be obvious. Hughes added that they were able to use the house because producer Ned Tanen knew the owner because they were both Ferrari collectors.[33]

According to Hughes, the scene at the Art Institute of Chicago was "a self-indulgent scene of mine—which was a place of refuge for me, I went there quite a bit, I loved it. I knew all the paintings, the building. This was a chance for me to go back into this building and show the paintings that were my favorite." The museum had not been shot in, until the producers of the film approached them.[20] "I remember Hughes saying, 'There are going to be more works of art in this movie than there have ever been before,'" recalled Jennifer Grey.[7] Among notable works featured in this scene include A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (Georges Seurat, 1884), during which Cameron struggles to find his identity in the face of one of the children in the painting, and America Windows (Marc Chagall, 1977), in front of which Ferris and Sloane have a romantic moment.[34]

According to editor Paul Hirsch, in the original cut, the museum scene fared poorly at test screenings until he switched sequences around and Hughes changed the soundtrack.[35]

The piece of music I originally chose was a classical guitar solo played on acoustic guitar. It was nonmetrical with a lot of rubato. I cut the sequence to that music and it also became nonmetrical and irregular. I thought it was great and so did Hughes. He loved it so much that he showed it to the studio but they just went "Ehhh." Then after many screenings where the audience said "The museum scene is the scene we like least", he decided to replace the music. We had all loved it, but the audience hated it. I said, 'I think I know why they hate the museum scene. It's in the wrong place.' Originally, the parade sequence came before the museum sequence, but I realized that the parade was the highlight of the day, there was no way we could top it, so it had to be the last thing before the three kids go home. So that was agreed upon, we reshuffled the events of the day, and moved the museum sequence before the parade. Then we screened it and everybody loved the museum scene! My feeling was that they loved it because it came in at the right point in the sequence of events. John felt they loved it because of the music. Basically, the bottom line is, it worked.[35]

The music used for the final version of the museum sequence is an instrumental cover version of The Smiths' "Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want", performed by The Dream Academy. A passionate Beatles fan, Hughes makes multiple references to them and John Lennon in the script. During filming, Hughes "listened to The White Album every single day for fifty-six days".[36] Hughes also pays tribute to his childhood hero Gordie Howe with Cameron's Detroit Red Wings jersey.[37] "I sent them the jersey", said Howe. "It was nice seeing the No. 9 on the big screen."[38]

Car

In the film, Ferris convinces Cameron to borrow his father's rare 1961 Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder. "The insert shots of the Ferrari were of the real 250 GT California", Hughes explains in the DVD commentary. "The cars we used in the wide shots were obviously reproductions. There were only 100 of these cars, so it was way too expensive to destroy. We had a number of replicas made. They were pretty good, but for the tight shots I needed a real one, so we brought one in to the stage and shot the inserts with it."[20]

Prior to filming, Hughes learned about Modena Design and Development who produced the Modena Spyder California, a replica of the Ferrari 250 GT.[39] Hughes saw a mention of the company in a car magazine and decided to research them. Neil Glassmoyer recalls the day Hughes contacted him to ask about seeing the Modena Spyder:

The first time he called I hung up on him because I thought it was a friend of mine who was given to practical jokes. Then he called back and convinced me it really was him, so Mark and I took the car to his office. While we were waiting outside to meet Hughes this scruffy-looking fellow came out of the building and began looking the car over; we thought from his appearance he must have been a janitor or something. Then he looked up at a window and shouted, 'This is it!' and several heads poked out to have a look. That scruffy-looking fellow was John Hughes, and the people in the window were his staff. Turned out it was between the Modena Spyder and a Porsche Turbo, and Hughes chose the Modena.[39]

Automobile restorationist Mark Goyette designed the kits for three reproductions used in the film and chronicled the whereabouts of the cars today:[40]

- "Built by Goyette and leased to Paramount for the filming. It's the one that jumps over the camera, and is used in almost every shot. At the end of filming, Paramount returned it to Goyette, with the exhaust crushed and cracks in the body. "There was quite a bit of superficial damage, but it held up amazingly well", he said. He rebuilt it, and sold it to a young couple in California. The husband later ran it off the road, and Goyette rebuilt the front end for him. That owner sold it in the mid-90s, and it turned up again around 2000, but hasn't emerged since."[40]

- "Sold to Paramount as a kit for them to assemble as their stunt car, they did such a poor job that it was basically unusable, aside from going backwards out the window of Cameron's house. Rebuilt, it ended up at Planet Hollywood in Minneapolis and was moved to Planet Hollywood in Cancun when this one was closed."[40]

- "Another kit, supposed to be built as a shell for the out the window scene, it was never completed at all, and disappeared after the film was completed. Goyette thinks he once heard it was eventually completed and sold off, but it could also still be in a back lot at Paramount."[40]

One of the "replicars" was sold by Bonhams on April 19, 2010, at the Royal Air Force Museum at Hendon, United Kingdom for £79,600 (equivalent to £128,912 in 2023).[41][42]

Another "replicar" used in the movie, serial number 001, referenced as the "hero car" that Goyette stated "hasn't emerged since" was sold at the 2020 Scottsdale Barrett-Jackson Collector Car Auction on January 18, 2020, for US$396,000 (equivalent to $466,218 in 2023).[43]

The "replicar" was "universally hated by the crew", said Ruck. "It didn't work right." The scene in which Ferris turns off the car to leave it with the garage attendant had to be shot a dozen times because it would not start.[7] The car was built with a real wheel base, but used a Ford V8 engine instead of a V12.[44] At the time of filming, the original 250 GT California model was worth $350,000.[7] Since the release of the film, it has become one of the most expensive cars ever sold, going at auction in 2008 for $10,976,000 (equivalent to $15,532,652 in 2023)[45] and more recently in 2015 for $16,830,000 (equivalent to $21,633,508 in 2023).[46] The vanity plate of Cameron's dad's Ferrari spells NRVOUS and the other plates seen in the film are homages to Hughes's earlier works, VCTN (National Lampoon's Vacation), TBC (The Breakfast Club), MMOM (Mr. Mom), as well as 4FBDO (Ferris Bueller's Day Off).

Economics lecture

Ben Stein's famous monotonous lecture about the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act was not originally in Hughes's script. Stein, by happenstance, was lecturing off-camera to the amusement of the student cast. "I was just going to do it off camera, but the student extras laughed so hard when they heard my voice that (Hughes) said do it on camera, improvise, something you know a lot about. When I gave the lecture about supply-side economics, I thought they were applauding. Everybody on the set applauded. I thought they were applauding because they had learned something about supply-side economics. But they were applauding because they thought I was boring. ... It was the best day of my life", Stein said.[24]

Parade scene

The parade scene took multiple days of filming; Broderick spent some time practicing the dance moves. "I was very scared", Broderick said. "Fortunately, the sequence was carefully choreographed beforehand. We worked out all the moves by rehearsing in a little studio. It was shot on two Saturdays in the heart of downtown Chicago. The first day was during a real parade, and John got some very long shots. Then radio stations carried announcements inviting people to take part in 'a John Hughes movie'. The word got around fast and 10,000 people showed up! For the final shot, I turned around and saw a river of people. I put my hands up at the end of the number and heard this huge roar. I can understand how rock stars feel. That kind of reaction feeds you."[47][48]

Broderick's moves were choreographed by Kenny Ortega (who later choreographed Dirty Dancing). Much of it had to be scrapped though as Broderick had injured his knee badly during the scenes of running through neighbors' backyards. "I was pretty sore", Broderick said. "I got well enough to do what you see in the parade there, but I couldn't do most of Kenny Ortega's knee spins and things like that that we had worked on. When we did shoot it, we had all this choreography and I remember John would yell with a megaphone, 'Okay, do it again, but don't do any of the choreography,' because he wanted it to be a total mess." "Danke Schoen" was somewhat choreographed but for "Twist and Shout", Broderick said, "we were just making everything up".[7] Hughes explained that much of the scene was spontaneously filmed. "It just happened that this was an actual parade, which we put our float into—unbeknownst to anybody, all the people on the reviewing stand. Nobody knew what it was, including the governor."[20]

Wrigley Field

Wrigley Field is featured in two interwoven and consecutive scenes. In the first scene, Rooney is looking for Ferris at a pizza joint while the voice of Harry Caray announces the action of a ballgame that is being shown on TV. From the play-by-play descriptions, the uniforms, and the player numbers, this game has been identified as the June 5, 1985, game between the Atlanta Braves and the Chicago Cubs.[25][49]

In the next scene, Sloane, Cameron, and Ferris are in the left field stands inside Wrigley. Ferris flexes his hand in pain after supposedly catching the foul ball. During this scene, the characters enjoy the game and joke about what they would be doing if they had played by the rules. All these "in the park" shots, including the one from the previous scene where Ferris catches the foul ball on TV, were filmed on September 24, 1985, at a game between the Montreal Expos and the Cubs. During the 1985 season, the Braves and the Expos both wore powder blue uniforms during their road games so, with seamless editing by Hirsch, it is difficult to distinguish that the game being seen and described in the pizza joint is not only a different game but also a different Cubs' opponent than the one filmed inside the stadium.[50]

On October 1, 2011, Wrigley Field celebrated the 25th anniversary of the film by showing it on three giant screens on the infield.[51]

Deleted scenes

Several scenes were cut from the final film; one lost scene titled "The Isles of Langerhans" has the three teenagers trying to order in the French restaurant, shocked to discover pancreas on the menu (although in the finished film, Ferris still says, "We ate pancreas", while recapping the day). This is featured on the Bueller, Bueller Edition DVD. Other scenes were never made available on any DVD version.[52] These scenes included additional screen time with Jeanie in a locker room, Ferris's younger brother and sister (both of whom were completely removed from the film), and additional lines of dialogue throughout the film, all of which can be seen in the original theatrical trailer. Hughes had also wanted to film a scene where Ferris, Sloane, and Cameron go to a strip club. Paramount executives told him there were only so many shooting days left, so the scene was scrapped.[7]

Music

Limited edition fan club soundtrack

An official soundtrack was not originally released for the film, as director John Hughes felt the songs would not work well together as a continuous album.[53] However, according to an interview with Lollipop Magazine, Hughes noted that he had sent 100,000 7" vinyl singles containing two songs featured in the film to members of his fan mailing list.[54]

Hughes gave further details about his refusal to release a soundtrack in the Lollipop interview:

The only official soundtrack that Ferris Bueller's Day Off ever had was for the mailing list. A&M was very angry with me over that; they begged me to put one out, but I thought "who'd want all of these songs?" I mean, would kids want "Danke Schoen" and "Oh Yeah" on the same record? They probably already had "Twist and Shout", or their parents did, and to put all of those together with the more contemporary stuff, like the (English) Beat—I just didn't think anybody would like it. But I did put together a seven-inch of the two songs I owned the rights to—"Beat City" on one side, and... I forget, one of the other English bands on the soundtrack... and sent that to the mailing list. By '86, '87, it was costing us $30 a piece to mail out 100,000 packages. But it was a labor of love.[54]

Songs in the film

"Danke Schoen" is one of the recurring motifs in the film and is sung by Ferris, Ed Rooney, and Jeanie. Hughes called it the "most awful song of my youth. Every time it came on, I just wanted to scream, claw my face. I was taking German in high school—which meant that we listened to it in school. I couldn't get away from it."[20] According to Broderick, Ferris's singing "Danke Schoen" in the shower was his idea. "Although it's only because of the brilliance of John's deciding that I should sing "Danke Schoen" on the float in the parade. I had never heard the song before. I was learning it for the parade scene. So we're doing the shower scene and I thought, 'Well, I can do a little rehearsal.' And I did something with my hair to make that Mohawk. And you know what good directors do: they say, 'Stop! Wait until we roll.' And John put that stuff in."[55]

2016 soundtrack

| Ferris Bueller's Day Off | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by various artists | |

| Released | September 13, 2016 |

| Genre | New wave |

| Length | 76:47 |

| Label | La-La Land Records |

The soundtrack for the film, limited to 5,000 copies, was released on September 13, 2016 by La-La Land Records. The album includes new wave and pop songs featured in the film, as well as Ira Newborn's complete score, including unused cues.[56] Due to licensing restrictions, "Twist and Shout," "Taking The Day Off," and "March of the Swivelheads" were not included, but are available elsewhere. The Flowerpot Men's "Beat City" makes its first official release on CD with a new mix done by The Flowerpot Men's Ben Watkins and Adam Peters that differs from the original 7" fan club release.[56][57]

Reception

Critical response

The film largely received positive reviews from critics. Roger Ebert gave it three out of four stars, calling it "one of the most innocent movies in a long time," and "a sweet, warm-hearted comedy."[58] Richard Roeper called the film: "one of my favorite movies of all time. It has one of the highest 'repeatability' factors of any film I've ever seen... I can watch it again and again. There's also this, and I say it in all sincerity: Ferris Bueller's Day Off is something of a suicide prevention film, or at the very least a story about a young man trying to help his friend gain some measure of self-worth... Ferris has made it his mission to show Cameron that the whole world in front of him is passing him by, and that life can be pretty sweet if you wake up and embrace it. That's the lasting message of Ferris Bueller's Day Off."[59] Roeper pays homage to the film with a license plate that reads "SVFRRIS".[60]

Conservative columnist George Will hailed Ferris as "the moviest movie," a film "most true to the general spirit of the movies, the spirit of effortless escapism."[61] Essayist Steve Almond called Ferris "the most sophisticated teen movie [he] had ever seen," adding that while Hughes had made a lot of good movies, Ferris was the "one film [he] would consider true art, [the] only one that reaches toward the ecstatic power of teendom and, at the same time, exposes the true, piercing woe of that age." Almond also applauded Ruck's performance, going so far as saying he deserved the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor of 1986: "His performance is what elevates the film, allows it to assume the power of a modern parable."[62] The New York Times reviewer Nina Darnton criticized Mia Sara's portrayal of Sloane for lacking "the specific detail that characterized the adolescent characters in Hughes's other films", asserting she "created a basically stable but forgettable character."[63][64] Conversely, Darnton praised Ruck and Grey's performances: "The two people who grow in the movie—Cameron, played with humor and sensitivity by Alan Ruck, and Ferris's sister Jeanie, played with appropriate self-pity by Jennifer Grey—are the most authentic. Grey manages to play an insufferably sulky teen-ager who is still attractive and likable."[63]

Co-star Ben Stein was exceptionally moved by the film, calling it "the most life-affirming movie possibly of the entire post-war period."[65] "This is to comedies what Gone with the Wind is to epics," Stein added. "It will never die, because it responds to and calls forth such human emotions. It isn't dirty. There's nothing mean-spirited about it. There's nothing sneering or sniggering about it. It's just wholesome. We want to be free. We want to have a good time. We know we're not going to be able to all our lives. We know we're going to have to buckle down and work. We know we’re going to have to eventually become family men and women, and have responsibilities and pay our bills. But just give us a couple of good days that we can look back on."[66]

National Review writer Mark Hemingway lauded the film's celebration of liberty. "If there's a better celluloid expression of ordinary American freedom than Ferris Bueller's Day Off, I have yet to see it. If you could take one day and do absolutely anything, piling into a convertible with your best girl and your best friend and taking in a baseball game, an art museum, and a fine meal seems about as good as it gets," wrote Hemingway.[67]

Others were less enamored with Ferris, many taking issue with the film's "rebel without a cause" hedonism. David Denby of New York Magazine, called the film "a nauseating distillation of the slack, greedy side of Reaganism."[68] Author Christina Lee agreed, adding it was a "splendidly ridiculous exercise in unadulterated indulgence," and the film "encapsulated the Reagan era's near solipsist worldview and insatiable appetite for immediate gratification—of living in and for the moment..."[69] Gene Siskel panned the film from a Chicago-centric perspective, saying: "Ferris Bueller doesn't do anything much fun ... [t]hey don't even sit in the bleachers where all the kids like to sit when they go to Cubs games."[70] Siskel did enjoy the chemistry between Jennifer Grey and Charlie Sheen. Ebert thought Siskel was too eager to find flaws in the film's view of Chicago.[70]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 80% based on 69 critics' reviews, with an average rating of 7.70/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "Matthew Broderick charms in Ferris Bueller's Day Off, a light and irrepressibly fun movie about being young and having fun."[71] Metacritic gave the film a score of 61 based on 13 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[72] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A-" on an A+ to F scale.[73]

Accolades

Broderick was nominated for a Golden Globe Award in 1987 for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy.[74]

Box office

The film opened in 1,330 theaters in the United States and had a total weekend gross of $6,275,647, opening at No. 2. Ferris Bueller's Day Off's total gross in the United States was approximately $70,136,369, making it a box office success.[2] It subsequently became the 10th-highest-grossing film of 1986.[75]

Rankings

As an influential and popular film, Ferris Bueller's Day Off has been included in many film rating lists. The film is number 54 on Bravo's "100 Funniest Movies", came 26th in the British 50 Greatest Comedy Films and ranked number 10 on Entertainment Weekly's list of the "50 Best High School Movies".[76]

Cultural impact

Hughes said of Bueller, "That kid will either become President of the United States or go to prison."[78] First Lady Barbara Bush paraphrased the film in her 1990 commencement address at Wellesley College: "Find the joy in life, because as Ferris Bueller said on his day off, 'Life moves pretty fast; if you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it!'" Responding to the audience's enthusiastic applause, she added "I'm not going to tell George you clapped more for Ferris than you clapped for George."[77][79]

Other phrases from Ferris Bueller's Day Off such as Stein's monotone-voiced "Bueller? ...Bueller? ...Bueller?" (while taking roll call in class), and "Anyone? Anyone?" (trying to probe the students for answers) as well as Kristy Swanson's cheerful "No problem whatsoever!" also permeated popular culture.[80] In fact, Stein's monotone performance launched his acting career.[81] In 2016, Stein reprised the attendance scene in a campaign ad[82] for Iowa Senator Charles Grassley; Stein intoned the last name of Grassley's opponent (Patty Judge), to silence, while facts about her missed votes and absences from state board meetings were listed. Stein then calls out "Grassley," which gets a response; Stein mutters, "He's always here."[83]

Broderick said of the Ferris Bueller role, "It eclipsed everything, I should admit, and to some degree it still does."[7] Later at the 2010 Oscar tribute to Hughes, he said, "For the past 25 years, nearly every day someone comes up to me, taps me on the shoulder and says, 'Hey, Ferris, is this your day off?'"[84]

Ruck says that with Cameron Frye, Hughes gave him "the best part I ever had in a movie, and any success that I've had since 1985 is because he took a big chance on me. I'll be forever grateful."[85] "While we were making the movie, I just knew I had a really good part", Ruck says. "My realization of John's impact on the teen-comedy genre crept in sometime later. Teen comedies tend to dwell on the ridiculous, as a rule. It's always the preoccupation with sex and the self-involvement, and we kind of hold the kids up for ridicule in a way. Hughes added this element of dignity. He was an advocate for teenagers as complete human beings, and he honored their hopes and their dreams. That's what you see in his movies."[85]

Broderick starred in a television advertisement prepared by Honda promoting its CR-V for the 2012 Super Bowl XLVI. The ad pays homage to Ferris Bueller, featuring Broderick (as himself) faking illness to skip out of work to enjoy sightseeing around Los Angeles. Several elements, such as the use of the song "Oh Yeah", and a valet monotonously calling for "Broderick... Broderick...", appear in the ad. A teaser for the ad had appeared two weeks prior to the Super Bowl, which had created rumors of a possible film sequel.[86] It was produced by Santa Monica-based RPA and directed by Todd Phillips.[87] AdWeek's Tim Nudd called the ad "a great homage to the original 1986 film, with Broderick this time calling in sick to a film shoot and enjoying another day of slacking."[87] On the other hand, Jalopnik's Matt Hardigree called the spot "sacrilegious".[88][89]

The film has been parodied in television series, with characters taking a day off from their normal routine to have a day of adventure. Examples include the episodes "Barry's Day Off" from The Goldbergs,[90] and "Brian Finch's Black Op" from Limitless.[91]

In March 2017, Domino's Pizza began an advertising campaign parodying the film, featuring actor Joe Keery in the lead role.[92]

In September 2020, LiftMaster released a commercial where two young boys attempt to drive a 1966 Jaguar E-Type owned by the father of one of the boys. The commercial, advertising the Liftmaster Secure View, a security system built into the device, features Alan Ruck as an older Cameron Frye, who warns the boys after catching them on camera. He then speaks to the audience "Been there, done that."[93][94]

Music

The film's influence in popular culture extends beyond the film itself to how musical elements of the film have been received as well, for example, Yello's song "Oh Yeah". As Jonathan Bernstein explains, "Never a hit, this slice of Swiss-made tomfoolery with its varispeed vocal effects and driving percussion was first used by John Hughes to illustrate the mouthwatering must-haveness of Cameron's dad's Ferrari. Since then, it has become synonymous with avarice. Every time a movie, TV show or commercial wants to underline the jaw-dropping impact of a hot babe or sleek auto, that synth-drum starts popping and that deep voice rumbles, 'Oh yeah . . .'"[95] Yello was unheard of in the United States at the time, but the inclusion of their song in Ferris Bueller and The Secret of My Success the following year sparked great interest in the song, where it reached the Billboard "Hot 100" and US Dance charts in 1987.[96][97] It often became referred to as "the Ferris Bueller song" due to its attachment with the movie.[98] Dieter Meier of Yello was able to use the licensing fees from "Oh Yeah"'s appearance in Ferris Bueller and other films to start a series of investments and amassed a large fortune.[99]

Concerning the influence of another song used in the film, Roz Kaveney writes that some "of the finest moments in later teen film draw on Ferris's blithe Dionysian fervour — the elaborate courtship by song in 10 Things I Hate About You (1999) draws usefully on the "Twist and Shout" sequence in Ferris Bueller's Day Off".[101] "Twist and Shout" charted again, 16 years after the Beatles broke up, as a result of its prominent appearance in both this film and Back To School (where Rodney Dangerfield performs a cover version) which was released the same weekend as Ferris Bueller's Day Off. The re-released single reached No. 23 in the U.S; a US-only compilation album containing the track The Early Beatles, re-entered the album charts at No. 197. The version heard in the film includes brass overdubbed onto the Beatles' original recording, which did not go down well with Paul McCartney. "I liked [the] film but they overdubbed some lousy brass on the stuff! If it had needed brass, we'd had stuck it on ourselves!"[100] Upon hearing McCartney's reaction, Hughes felt bad for "offend[ing] a Beatle. But it wasn't really part of the song. We saw a band [onscreen] and we needed to hear the instruments."[20]

The bands Save Ferris and Rooney were named in allusion to Ferris Bueller's Day Off.[102]

Sequel talks

Broderick and Hughes stayed in touch for a while after production. "We thought about a sequel to Ferris Bueller, where he'd be in college or at his first job, and the same kind of things would happen again. But neither of us found a very exciting hook to that. The movie is about a singular time in your life."[55] "Ferris Bueller is about the week before you leave school, it's about the end of school— in some way, it doesn't have a sequel. It's a little moment and it's a lightning flash in your life. I mean, you could try to repeat it in college or something but it's a time that you don't keep. So that's partly why I think we couldn't think of another," Broderick added.

"But just for fun," said Ruck, "I used to think why don't they wait until Matthew and I are in our seventies and do Ferris Bueller Returns and have Cameron be in a nursing home. He doesn't really need to be there, but he just decided his life is over, so he committed himself to a nursing home. And Ferris comes and breaks him out. And they go to, like, a titty bar and all this ridiculous stuff happens. And then, at the end of the movie, Cameron dies."[7]

Academic analysis

Many scholars have discussed at length the film's depiction of academia and youth culture. For Martin Morse Wooster, the film "portrayed teachers as humorless buffoons whose only function was to prevent teenagers from having a good time".[103] Regarding not specifically teachers, but rather a type of adult characterization in general, Art Silverblatt asserts that the "adults in Ferris Bueller's Day Off are irrelevant and impotent. Ferris's nemesis, the school disciplinarian, Mr. Rooney, is obsessed with 'getting Bueller.' His obsession emerges from envy. Strangely, Ferris serves as Rooney's role model, as he clearly possesses the imagination and power that Rooney lacks. ... By capturing and disempowering Ferris, Rooney hopes to ... reduce Ferris's influence over other students, which would reestablish adults, that is, Rooney, as traditional authority figures."[104] Nevertheless, Silverblatt concludes that "Rooney is essentially a comedic figure, whose bumbling attempts to discipline Ferris are a primary source of humor in the film".[104] Thomas Patrick Doherty writes that "the adult villains in teenpics such as ... Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986) are overdrawn caricatures, no real threat; they're played for laughs".[105] Yet Silverblatt also remarks that casting "the principal as a comic figure questions the competence of adults to provide young people with effective direction—indeed, the value of adulthood itself".[104]

Adults are not the stars or main characters of the film, and Roz Kaveney notes that what "Ferris Bueller brings to the teen genre, ultimately, is a sense of how it is possible to be cool and popular without being rich or a sports hero. Unlike the heroes of Weird Science, Ferris is computer savvy without being a nerd or a geek — it is a skill he has taken the trouble to learn."[106]

In 2010, English comedian Dan Willis performed his show "Ferris Bueller's Way Of..." at the Edinburgh Festival, delving into the philosophy of the movie and looking for life answers within.[107]

Home media and other releases

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

The film has been released on DVD three times; including on October 19, 1999, on January 10, 2006, as the Bueller... Bueller edition, and the I Love the '80s edition August 19, 2008.[108] The original DVD, like most Paramount Pictures films released on DVD for the first time, has very few bonus features, but it does feature a commentary by Hughes. Though this is no longer available for sale, the director's commentary is available.[109] The DVD was issued in the United States on October 19, 1999, the United Kingdom on July 31, 2000, Germany on August 3, 2000, Denmark on August 9, 2000, Brazil on June 25, 2001, and Canada on March 9, 2004. The North American DVDs include a Dolby Digital 5.1 Surround Sound English audio track, a mono version of the French dub, and English subtitles. The German, Danish, and UK DVD includes the English and French audio as well as mono dubs in German, Italian, and Spanish. The German and Danish release features English, French, German, Portuguese, Bulgarian, Croatian, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian, Swedish, and Turkish subtitles, the UK including those minus the Finnish subtitles and plus the Romanian subs. The Brazilian DVD only has the English audio and English, Portuguese and Spanish subtitles.

The Bueller... Bueller DVD re-release has several more bonus features, but does not contain the commentary track of the original DVD release. The edition was released in the United States on January 10, 2006, Sweden on April 12, 2006, Spain on April 18, 2006, and the United Kingdom on May 29, 2006. The I Love the '80s edition is identical to the first DVD release (no features aside from commentary), but includes a bonus CD with songs from the 1980s. The songs are not featured in the film. The Bueller... Bueller edition has multiple bonus features such as interviews with the cast and crew, along with a clip of Stein's commentaries on the film's philosophy and impact.[108]

Bueller... Bueller... editions were also the first Blu-ray releases of Ferris Bueller's Day Off. Blu-rays of the edition were released in the United States and Canada on May 5, 2009; Australia on June 16, 2009; Brazil on July 20, 2009; and United Kingdom on February 1, 2010. All of these Blu-rays feature a Dolby TrueHD audio track of the English version, with mono versions of the French and Spanish dubs; they also include English, French, Spanish and Portuguese subtitles. A 25th anniversary edition for DVD and Blu-ray were both released on August 2, 2011, in North America.

On October 18, 2004, Ferris Bueller's Day Off was issued as part of a UK Digipack DVD collection by Paramount Pictures named I Love 80s Movies: John Hughes Classic 80s, which also included Pretty in Pink (1986), Planes, Trains, and Automobiles (1987), and Some Kind of Wonderful (1987). It was later part of the United States Warner Bros. DVD set 5 Film Collection: 80's Comedy, issued on September 30, 2014, and also including Planes, Trains and Automobiles, The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad! (1988), Airplane! (1980), and Police Academy (1984); the collection also included digital files of the films. On October 3, 2017, it was released in the United States as part of the DVD collection 5 Iconic Films of the 80s that also included The Naked Gun, Some Kind of Wonderful, Crocodile Dundee (1986), and Harlem Nights (1989). The film also appeared on two Blu-ray collections: Australia's Films That Define A Decade – 80s Collection released on April 12, 2017, and France's Pop Culture Anthology 20 Films Cultes Blu-ray issued on October 17, 2018.

In the United Kingdom, an 80s Collection edition with new artwork was released on DVD in 2018 with the same six bonus features as the 2006 issue.[110]

In 2016 Paramount, Turner Classic Movies, and Fathom Events re-released the film and Pretty in Pink to celebrate their 30th anniversary.[111]

Most Blu-ray debuts of Ferris Bueller's Day Off in most foreign-language countries took place in 2019; the film was released to the format in France on January 9, 2019, Germany on February 7, 2019, Italy on March 13, 2019,Japan on April 24, 2019, and Spain on May 3, 2019. The Italy, Germany, and Spain Blu-rays includes French, German, Italian, and Spanish dubs; and Italian, English, French, German, Japanese, Spanish, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish subtitles. The French and Japanese Blu-rays, however, are limited to subtitle and audio options of their respective languages. VHS retro packing Blu-ray editions of the film have only been issued as retailer exclusives. In Australia on December 6, 2017, JB Hi-Fi issued a 1000-copies-only "Rewind Collection" edition of the VHS-retro-packaged Blu-ray that also includes a DVD disc, a toy figure, props from the film, and other memorabilia. On July 30, 2018, HMV exclusively released the same limited edition in the United Kingdom.

Television series

In 1990, a series called Ferris Bueller started for NBC, starring Charlie Schlatter as Ferris Bueller and Jennifer Aniston as Jeanie Bueller.[112] Jennifer Aniston and Jennifer Grey would subsequently appear together in one episode of the sitcom Friends, their characters (Rachel and Mindy) being the former and current fiancée of Barry Farber. Mindy returns in one further episode but played by another actress.

References

- ^ "'Ferris Bueller' celebrates middle age at Gun Bun". August 12, 2016. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ a b "Ferris Buellers's Day Off". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Ferris Bueller: John Hughes and Chicago". AMC Movie Blog. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ^ Grow, Kory (December 17, 2014). "'Big Lebowski,' 'Ferris Bueller' Added to National Film Registry - Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "Cinematic Treasures Named to National Film Registry". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Gora, Susannah (February 9, 2010). You Couldn't Ignore Me If You Tried. The Brat Pack, John Hughes, and Their Impact on a Generation. Crown. p. 176. ISBN 978-0307408433.

- ^ Kamp, David (March 2010). "Sweet Bard of Youth". Vanity Fair. p. 5. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ a b McGrath, Declan (2001). Editing & post-production. p. 79. ISBN 0-240-80468-6.

- ^ "Ferris Bueller: John Hughes and Speedwriting". AMC Movie Blog. April 10, 2007. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ McNally, Edward (August 12, 2009). "A Mirror Up To the Original Ferris Bueller". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ a b Barrett, Sharon (June 13, 1986). "Broderick taps charm in 'Day Off'". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ Harris, Will (July 8, 2018). "Alan Ruck's journey from Ferris Bueller to Sears to the bridge of the Enterprise and beyond". The AV Club. Onion, Inc. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ Guerrasio, Jason (2021). "Anthony Michael Hall says he regrets turning down the lead role in 'Ferris Bueller's Day Off'". Insider.

- ^ a b Kandell, Zachary (March 14, 2020). "Ferris Bueller's Day Off: The Actors Who Almost Played Ferris". Screenrant. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Diana Pearl; Maria Yagoda (September 2, 2021). "Iconic Roles That Were Almost Played by Another Actor". People.

it could have been Depp twisting-and-shouting through the streets of Chicago. The future 21 Jump Street star was John Hughes's first choice for the title role, but he had to turn it down due to scheduling conflicts.

- ^ Evans, Bradford (March 17, 2011). "The Lost Roles of Jim Carrey". Splitsider. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Scott, Vernon (July 16, 1986). "Mia Sara Lands Plum Roles Despite Lack of Training". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ a b c Haithman, Diane (July 3, 1986). "Ruck Just Put Himself Into His 'Day Off' Role". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ferris Bueller's Day Off-(Commentary by John Hughes) (DVD). Paramount Pictures. October 19, 1999.

- ^ a b "Q and A with Jeffrey Jones". Pop Culture Corn. July 2000. Archived from the original on September 24, 2010. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ^ Coozer, Adam (October 30, 1997). "Jeffrey Jones". ReadJunk. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ^ Honeycutt, Kirk (March 25, 2015). John Hughes: A Life in Film: The Genius Behind Ferris Bueller, The Breakfast Club, Home Alone, and more. Race Point Publishing. ISBN 978-1631060229.

- ^ a b c Presenters: A.J. Hammer and Brooke Anderson (January 10, 2006). "Ben Stein Talks about Famous "Ferris Bueller" Role". Showbiz Tonight. CNN. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ a b Granillo, Larry (February 6, 2011). "Ferris Bueller's Day Off at Wrigley Field". Baseball Prospectus. Archived from the original on February 10, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Ferris Bueller's Day Off: Miscellaneous Notes". Turner Classic Movies (TCM). Archived from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ a b "Save Ferris: The Ultimate Map Guide to Ferris Bueller". Curbed. October 7, 2014. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ "Chicago: The Ferris Bueller high school". The A.V. Club. July 29, 2011. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ Drash, Wayne (August 26, 2019). "From Ferris Bueller to opioid trial: A judge's wild ride into history". CNN. Archived from the original on August 26, 2019. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- ^ "For Sale: Property Information for 370 Beech Street". 'Realtor.com. May 27, 2009. Archived from the original on May 28, 2009. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- ^ "Rose House and Pavilion". December 28, 2011. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009.

- ^ a b "Rose House and Pavilion". Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: 'Ferris Bueller's Day Off' - John Hughes Commentary - Car Crash. August 13, 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Nodjimbadem, Katie (June 1, 2016). "How Ferris Bueller's Day Off Perfectly Illustrates the Power of Art Museums". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Oldham, Gabriella (1995). First Cut: Conversations with Film Editors. University of California Press. pp. 191–192. ISBN 0-520-07588-9.

- ^ "Molly Ringwald Interviews John Hughes". Seventeen. Spring 1986.

- ^ McDermott, John (June 11, 2016). "Why Cameron Frye Wore a Gordie Howe Jersey in 'Ferris Bueller's Day Off'". MEL Magazine. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ Markazi, Arash (May 5, 2009). "Q&A with Gordie Howe". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on January 14, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Miersma, Seyth (June 29, 2013). "Ferrari California replica from Ferris Bueller is so choice". Auto Blog. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Adolphus, David Traver (December 1, 2009). "Save these Cars – Hollywood, California: Part II". Hemmings Auto blog. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ "Ferrari replica created for Ferris Bueller's Day Off for sale". The Daily Telegraph. March 30, 2010. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ Campbell, Christopher (March 30, 2010). "Buy the 'Ferris Bueller' Ferrari For Only $67,000". Cinematical.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "1963 MODENA SPYDER CALIFORNIA #GTC0001 'FERRIS BUELLer's DAY - Barrett-Jackson Auction Company - World's Greatest Collector Car Auctions". Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "Ferris Bueller's Day Off Ferrari". Uncrate. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ tgriffith (May 22, 2009). "The Five Most Expensive Cars Ever Sold At Auction". The CarGurus Blog. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Blackwell, Rusty (August 18, 2015). "Hammer Down: The 25 Most Expensive Cars at the 2015 Monterey Auctions". Car and Driver. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (June 19, 1986). "Sad Wise Eyes in a Boy's Face". Argus-Press. Associated Press. p. 9. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (June 19, 1986). "Young star of Ferris Bueller seeks to get away from high school roles". Ottawa Citizen. Associated Press. pp. F17. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ Zaleski, Annie (June 5, 2015). "Ferris Bueller's actual day off was 30 years ago today". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on June 6, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ Larry Granillo (February 8, 2011). "Ferris Bueller Follow-up". Baseball Prospectus. Archived from the original on February 12, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Ferris Bueller returns to Wrigley Field". ESPN. October 1, 2011. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ Chaney, Jen: "'Bueller, Bueller' Edition Almost Saves 'Ferris' Archived November 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine", The Washington Post, January 10, 2006

- ^ Ham, William. "John Hughes: Straight Outta Sherman". Lollipop Magazine. Archived from the original on August 19, 2000. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Lollipop Magazine article: "John Hughes – Straight Outta Sherman Archived August 19, 2000, at the Wayback Machine" By William Ham.

- ^ a b Kamp, David (March 20, 2010). "John Hughes' Actors on John Hughes". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Yoo, Noah (September 6, 2016). "Ferris Bueller's Day Off Soundtrack to Get First Official Release". Pitchfork.com. Archived from the original on September 7, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ O'Neal, Sean (September 6, 2016). "Ferris Bueller's Day Off soundtrack arrives after skipping the past 30 years". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on September 7, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 11, 1986). "Ferris Bueller's Day Off movie review (1986)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (August 7, 2009). "'Ferris' could never go too far, to our delight". Richard Roeper. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (August 7, 2009). "Save Ferris". Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ Will, George F (June 28, 1986). "Finally...a 'movie' movie". Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ Almond, Steve (2006). "John Hughes Goes Deep: The Unexpected Heaviosity of Ferris Bueller's Day Off". Virginia Quarterly Review. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ a b Darnton, Nina (June 11, 1986). "SCREEN: A YOUTH'S DAY OFF". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Timesmachine.nytimes.com". The New York Times. June 11, 1986. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ Preston, Mark (July 28, 2008). "Preston on Politics: Bueller? Bueller? -- McCain needs Rove". CNN. Archived from the original on September 12, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ Ferris Bueller's Day Off-(World According to Ben Stein) (DVD). Paramount Pictures. 2006.

- ^ Hemingway, Mark (August 10, 2009). "Missing John Hughes". National Review. Archived from the original on August 31, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ Denby, David (December 22, 1986). "Movies". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ Christina, Lee (2010). Screening Generation X: the politics and popular memory of youth in contemporary cinema. ISBN 978-0-7546-4973-1.

- ^ a b Siskel, Gene; Ebert, Roger (1986). "Ferris Bueller". At the Movies.

- ^ "Ferris Bueller's Day Off". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ "Ferris Bueller's Day Off Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "Cinemascore :: Movie Title Search". December 20, 2018. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ "Winners & Nominees 1987". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on September 7, 2017. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ "Ferris Bueller's Day Off – Bueller Bueller Edition". Archived from the original on February 9, 2006. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ 50 Best High School Movies Archived August 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ a b Barbara Pierce Bush, Commencement Address at Wellesley College (June 1, 1990) Americanrhetoric.com Archived January 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ O’Rourke, P. J. (March 22, 2015). "Don't You Forget About Me: The John Hughes I Knew". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Chaney, Jen (June 10, 2011). "'Ferris Bueller's Day Off' and its 25 contributions to pop culture lore". Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Andrews, Casandra (February 5, 2006). "The cast of Bueller: Where are they now?". Press-Register.

- ^ Schurenberg, Eric (March 13, 2008). "Ben Stein: What, him worry?". Money. Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ Ad may be viewed at Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Judge advertisement. Retrieved January 17, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Robillard, Kevin, Politico, October 21, 2016, "Ben Stein reprises 'Bueller' role in Grassley ad Archived July 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ Braxton, Greg (March 8, 2010). "John Hughes High School reunion". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ a b "John Hughes Remembered: Alan Ruck, Cameron from 'Ferris Bueller'". Entertainment Weekly. August 13, 2009. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Manker, Rob (January 30, 2012). "Honda releases complete Ferris Bueller ad". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ a b "Honda Unveils Ferris Bueller Ad, and It Is Awesome". AdWeek. January 30, 2012. Archived from the original on January 31, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ^ Hardigree, Matt (January 30, 2012). "SAVE FERRIS From Honda's Sacrilegious Super Bowl Ad". Jalopnik. Archived from the original on February 1, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ "'Ferris Bueller' stars in Honda Super Bowl advert". The Telegraph. January 30, 2012. Archived from the original (Article, video) on January 6, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ Harris, Will (February 26, 2015). "The Middle: "Steaming Pile of Guilt" / The Goldbergs: "Barry Goldberg's Day Off"". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ Coggan, Devan (November 4, 2015). "'Limitless' recap: 'Brian Finch's Black Op'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ "Domino's Pizza channels 'Ferris Bueller's Day Off' in latest ad campaign". Fox News. March 21, 2017. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ Scott Stump (October 1, 2020). "Watch Alan Ruck revisit iconic 'Ferris Bueller' scene in new ad (ooohhh yeahhh!)". TODAY.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ LiftMaster Secure View - Oh Yeah!. LiftMaster. September 28, 2020. Archived from the original on October 3, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ Jonathan Bernstein, Pretty in pink: the golden age of teenage movies (Macmillan, 1997), 198 Archived May 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Yello: 'Oh Yeah'". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2004). Hot Dance/Disco: 1974-2003. Record Research. p. 285.

- ^ Blake, Boston (August 19, 2016). "The 20 Most Overused Songs In Movies And TV". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

Of its inclusion in the movie, writer and critic Jonathan Berstein claimed its use by John Hughes illustrated the "mouthwatering must-haveness of Cameron's dad's Ferrari. Since then, it has become synonymous with lust."

- ^ Letzing, John (January 27, 2017). "A-HED 'Oh Yeah,' the Song from 'Ferris Bueller's Day Off,' Is Catchy, Irritating and the Origin of an Investing Fortune". Wall Street Journal. Zurich. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

The quirky techno tune, which accompanied Ferris's Ferrari escapade and loads of other advertisements and Hollywood comedies, helped create a lucrative investment career for its Swiss co-creator

- ^ a b Dowlding, William (1989). Beatlesongs. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-68229-6.

- ^ Roz Kaveney, Teen dreams: reading teen film from Heathers to Veronica Mars (I.B.Tauris, 2006), 45 Archived May 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Eby, Margaret (2012). Rock and Roll Baby Names: Over 2,000 Music-Inspired Names, from Alison to Ziggy. Penguin.

- ^ Martin Morse Wooster, Angry classrooms, vacant minds: what's happened to our high schools? (Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy, 1993), 75.

- ^ a b c Art Silverblatt, Genre Studies in Mass Media: A Handbook (M.E. Sharpe, 2007), 105 Archived November 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Thomas Patrick Doherty, Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s (Temple University Press, 2002) 196 Archived May 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Roz Kaveney, Teen dreams: reading teen film from Heathers to Veronica Mars (I.B.Tauris, 2006) 44 Archived May 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Stubbs, Jamie (August 12, 2010). "Ferris Buellers Way of REVIEW". Giggle Beats. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ^ a b "Ferris Saved for Blu-ray". IGN. June 7, 2011. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "Long Lost 'Ferris Bueller's Day Off' Director's Commentary Resurfaces". Screencrush.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ "Ferris Bueller's Day Off – 80s Collection". Amazon. 2018. Archived from the original on February 19, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ "Ferris Bueller's Day Off: 30th Anniversary". Fathom Events. Archived from the original on February 11, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 27, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

- Ferris Bueller's Day Off at IMDb

- Ferris Bueller's Day Off at the TCM Movie Database

- Template:Amg movie

- Ferris Bueller's Day Off at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Ferris Bueller's Day Off at Box Office Mojo

- 1986 films

- Ferris Bueller's Day Off

- 1980s teen comedy films

- American coming-of-age comedy films

- American films

- American high school films

- American teen comedy films

- English-language films

- Films about educators

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films directed by John Hughes (filmmaker)

- Films produced by John Hughes (filmmaker)

- Films scored by Ira Newborn

- Films set in Chicago

- Films shot in Chicago

- Paramount Pictures films

- Films with screenplays by John Hughes (filmmaker)

- United States National Film Registry films

- 1986 comedy films

- Films set in museums

- Chicago Cubs