Joss paper

| Joss paper | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Traditional joss paper (金紙) sold in stacks at a store | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 金紙 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 金纸 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | gold paper | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 陰司紙 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 阴司纸 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | netherworld paper | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 紙錢 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 纸钱 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | paper money | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Third alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 冥幣 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 冥币 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | shade/dark money | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Joss paper, also known as incense papers, are papercrafts or sheets of paper made into burnt offerings common in Chinese ancestral worship (such as the veneration of the deceased family members and relatives on holidays and special occasions). Worship of deities in Chinese folk religion also uses a similar type of joss paper. Joss paper, as well as other papier-mâché items, are also burned or buried in various Asian funerals, "to ensure that the spirit of the deceased has sufficient needs in the afterlife." In Taiwan alone, the annual revenue of temples received from burning joss paper was US$400 million (NT$13 billion) as of 2014.[1]

Traditional

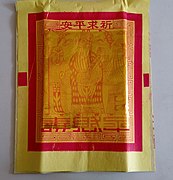

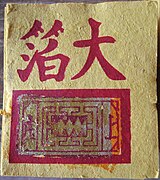

Joss paper is traditionally made from coarse bamboo paper, which feels handmade with many variances and imperfections, although rice paper is also commonly used. Traditional joss is cut into individual squares or rectangles. Depending on the region, Joss paper may be decorated with seals, stamps, pieces of contrasting paper, engraved designs or other motifs.

Different types of spirit money are given to distinct categories of spirits.[2][3][4][5] The three main types of spirit money are cash (also known as copper), silver and gold. Cash monies are given to newly deceased spirits and spirits of the unknown. Golden Joss papers (jin) are mostly offered to the Deities such as the Jade Emperor. Silver Joss paper (ying) is given exclusively to ancestral spirits as well as other spirits. These distinctions between the three categories of spirit money must be followed precisely to avoid confusing or insulting the spirits.

-

Dabai Shoujin (大百壽金, lit. "longevity gold"): large paper squares with a golden metallic rectangle imprinted with Fu, Lu & Shou (Three Stars), can be offered to heavenly Deities.

-

Yijin (刈金, lit. "cut gold"): large paper squares with a golden metallic rectangle, can be offered to any level of Deities.

-

Jiujin (九金, lit. "nine gold"): large paper squares with a golden metallic rectangle and printed with angled shapes and characters, popular in Southern Taiwan, used to be offered to Deities's spiritual soldiers, more common offer in ancestral worship and earth guardians nowadays.

-

Xiaoyin (小銀, lit. "lesser silver"): small paper squares with a silver metallic rectangle, burned for close relatives, ancestors and spirits.

-

Jingyi (經衣, lit. "threads and clothes"): A type of joss paper with images of items needed by the dead as "daily necessity", such as clothes, shoes, cups, and scissors, printed on the surface.

Contemporary

This section possibly contains original research. (February 2022) |

More contemporary or westernized varieties of Joss paper include paper currency, credit cards, cheques, as well as papier-mâché clothes, houses, cars, toiletries, electronics and servants (together known as Zhizha in Mandarin zhǐzhā zh:紙紮). The designs on paper items vary from the very simple to very elaborate (with custom artwork and names).

In 2006, in response to the burning of "messy sacrificial items", such as paper cars, houses, and pills, Dou Yupei, the PRC deputy minister for civil affairs, announced that the ministry intended to ban at least the more extreme forms of joss paper.[6]

"Hell Bank Notes"

Much like the traditional gold and silver paper, Hell Bank Notes serve as the official currency for the afterlife. Living relatives offer them to dead ancestors by burning (or placing them in coffins in the case of funerals) the bank notes as a bribe to Yanluo for a shorter stay or to escape punishment, or for the ancestors themselves to use in spending on lavish items in the afterlife.

The word "hell" may have been derived from:

- The preaching of Christian missionaries, who told the Chinese that non-Christians and their ancestors would go to hell when they died as non-believer.

- A translation of the word "hell" that matches the pre-existing Chinese concept of "underworld realm," which in Taoist cosmology had been considered the one of the destinations on the journey of rebirth of every soul of the dead regardless of his or her virtue during life.

Hell Bank Notes are also known for their enormous denominations ranging from $10,000 to $5,000,000,000. The bills almost always feature an image of the Yanluo Wang on the front and the "headquarters" of the Hell Bank on the back. Another common feature is the signatures of both the Yanluo Wang and the Judges of Underworld, both of whom apparently also serve as the Hell bank's governor and deputy governor (as featured on the back).

Use

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2013) |

Spirit money is most often used for venerating those departed but has also been known to be used for other purposes such as a gift from a groom's family to the bride's ancestors. Spirit money has been said to have been given for the purpose of enabling their deceased family members to have all they will need or want in the afterlife. It has also been noted that these offerings have been given as a bribe to Yanluo Wang to hold their ancestors for a shorter period of time.

Venerating the ancestors is based on the belief that the spirits of the dead continue to dwell in the natural world and have the power to influence the fortune and fate of the living. The goal of ancestor worship is to ensure the ancestor's continued well-being and positive disposition towards the living and sometimes to ask for special favours or assistance. Rituals of ancestor worship most commonly consist of offerings to the deceased to provide for their welfare in the afterlife which is envisioned to be similar to the earthly life. The burning of spirit money enables the ancestor to purchase luxuries and necessities needed for a comfortable afterlife.

Many temples have large furnaces outside the main gate to burn joss paper. Folding the paper is an essential part of the burning ceremony as it distinguishes joss paper from actual money; and, it provides good luck for those who fold it. Burning actual money would be untenable for most people, and is also considered unlucky in Asian cultures. The Joss paper may be folded into specific shapes which are meant to bring on good luck and people tend to burn lavish amounts to ensure that the offering is well received.

Every fifteen days business owners in Taiwan burn spirit money in red braziers and set out offering tables on the sidewalk for both gods and ghosts. This coincides with an ancient calendrical system divided into twenty-four fifteen-day periods.

A simplified modern Chinese offering is made by drawing a circle with chalk on the sidewalk or the pavement between residential buildings and burning the paper offering within the circle. This is quite common in all Chinese cities and villages today.

Due to environmental concerns, contemporary Joss paper burners are now fitted with a special cover which eliminates the spread of burning ashes. The cover allows enough oxygen in to ensure that all of the offering are completely burned.

Spirit money is most commonly burned, but may also be offered by being held into the wind or placed into the deceased's coffin at funeral ceremonies.

Depending on the type and status of the deity being worshiped, paper with metal foil or with ink seals of various sizes may be burned. Different regions of the world have different preferences for the type of Joss paper that is used. For instance, Hell Bank Notes are commonly found in regions where Cantonese populations dominate but are rarely seen or used in places such as Taiwan or Macau, which use "gold paper". The Joss paper is folded in half, or bought pre-folded into the shape of gold ingots before being burned in an earthenware pot or a specially built chimney. Joss paper burning is usually the last performed act in Chinese deity or ancestor worship ceremonies. The papers may also be folded and stacked into elaborate pagodas or lotuses.

In Taoist rituals, the practice of offering joss paper to deities or ancestors is an essential part of the worship. Some Chinese Buddhist temples, such as Singapore Buddhist Lodge in Singapore, have discouraged offering of joss papers during ancestral worship in their ancestral tablet hall out of concern for the environmental pollution.

Health impact

Metal contents analysis of ash samples shows that joss paper burning emits a lot of toxic components causing health risks. Studies showed that there is a significant amount of heavy metals in the dust fume and bottom ash in order Al < Fe < Mn < Cu < Pb < Zn < Cd.[7][8] Another study found that burning gold and silver joss papers during festivals can contribute to Parkinson's disease among the elderly and slow child development.[9] Burning of joss paper may also contributes to a condition called metal fume fever. Certain provinces in China have banned the burning of ghost paper out of concern for the air pollution it causes.[10]

See also

- Chinese ancestral worship

- Qingming Festival

- Zhong Yuan Festival

- Ancestral tablet

- Ancestral temple

- Chinese lineage associations & Kongsi

- Zhizha & Religious goods store

- Papier-mache offering shops in Hong Kong

- Chinese burial money

- Hell money

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2009) |

- ^ Everington, Keoni (2016-11-08). "Monks gone wild: Fast and furious nuns, monks peering at porn". Taiwan News. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ^ 拜 神 教 室

- ^ 簡介:冥鏹及衣紙

- ^ 衣紙2 Archived 2012-03-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 拜神用的金銀元寶衣紙及其他的排列次序

- ^ A New Chinese Trend: Viagra For the Dead - March 22, 2007 - The New York Sun

- ^ Heavy metals emissions from joss paper burning rituals and the air quality around a specific incinerator

- ^ Annual Air Pollution Caused by the Hungry Ghost Festival

- ^ Doctors warn on toxic incense, joss papers

- ^ To Improve Air Quality, Harbin Bans Burning Ghost Money

- Adler, J. (2002). Chinese Religious Traditions. London: Laurence King Publishing, Ltd.

- Asian Joss Paper: Rubber Trouble. Retrieved October 23, 2008 from http://rubbertrouble.com/joss.php

- Burning of Joss Paper. Retrieved October 23, 2008 from https://web.archive.org/web/20070713050534/http://app.nea.gov.sg/cms/htdocs/article.asp?pid=720

- Feuchtwang, S. (2001). Popular Religion in China. Surrey: Curzon Press.

- Gates, H. (1987, July). Money for the Gods. Modern China, 13(3), 259-277. Retrieved from JSTOR database.

- Hell bank notes - Library - Collection - Studio - Collectors Software. Retrieved October 23, 2008 from [1]

- Joss Paper. Retrieved October 24, 2008

- Seaman, G. (1982 Fall). Spirit Money: An Interpretation. Journal of Chinese Religions.

- Thompson, L. (1989). Chinese Religion. Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing Company.