Carpenter Gothic

Carpenter Gothic, also sometimes called Carpenter's Gothic or Rural Gothic, is a North American architectural style-designation for an application of Gothic Revival architectural detailing and picturesque massing applied to wooden structures built by house-carpenters. The abundance of North American timber and the carpenter-built vernacular architectures based upon it made a picturesque improvisation upon Gothic a natural evolution. Carpenter Gothic improvises upon features that were carved in stone in authentic Gothic architecture, whether original or in more scholarly revival styles; however, in the absence of the restraining influence of genuine Gothic structures,[1] the style was freed to improvise and emphasize charm and quaintness rather than fidelity to received models. The genre received its impetus from the publication by Alexander Jackson Davis of Rural Residences and from detailed plans and elevations in publications by Andrew Jackson Downing.

History

Carpenter Gothic houses and small churches became common in North America in the late nineteenth century.[2] These structures adapted Gothic elements, such as pointed arches, steep gables, and towers, to traditional American light-frame construction. The invention of the scroll saw and mass-produced wood moldings allowed a few of these structures to mimic the florid fenestration of the High Gothic. But in most cases, Carpenter Gothic buildings were relatively unadorned, retaining only the basic elements of pointed-arch windows and steep gables. Probably the best known example of Carpenter Gothic is the house in Eldon, Iowa, that Grant Wood used for the background of his famous painting American Gothic.[3]

Characteristics

Carpenter Gothic is largely confined to small domestic buildings and outbuildings and small churches. It is characterized by its profusion of jig-sawn details, whose craftsmen-designers were freed to experiment with elaborate forms by the invention of the steam-powered scroll saw. A common but not necessary feature is board and batten siding. Other common features include decorative bargeboards, gingerbread trim, pointed-arched windows, wheel window, one-story veranda, and steep central gable.[4] A less common feature is buttressing, especially on churches and larger houses.

Ornamental use

Carpenter Gothic ornamentation, referred to as gingerbread, is not limited to use on wooden structures but has been used successfully on other structures especially Gothic Revival brick houses such as the Warren House in a historic district in Newburgh, New York, which is said to epitomize the work of Andrew Jackson Downing, but was actually done by his one-time partner, Calvert Vaux.

Geographic extent

Carpenter Gothic structures are typically found in most states of the United States, except Arizona and New Mexico. There is one Carpenter Gothic in the Huning Highlands Historical District in downtown Albuquerque circa 1882 built by the Seth family who lived there until 2002. Many Carpenter Gothic houses were built in Nevada in the 1860-1870s (Virginia City, Reno, Carson City, and Carson Valley areas) and still exist (2010). In Canada, carpenter Gothic places of worship are found in all provinces and the Northwest Territories, while Carpenter Gothic houses seem to be limited to Ontario, Quebec and the Maritime Provinces.[5]

Endangered Carpenter Gothic buildings

Many American Carpenter Gothic structures are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, which may help to ensure their preservation. Many, though, are not listed and those in urban areas are endangered by the increased value of the land they occupy.

A current example of this is St. Saviour's Episcopal Church, Maspeth, New York, built in 1847 by Richard Upjohn.[6] It was sold to a developer in 2006. Its rectory had already been demolished and a deal with the City of New York to preserve the church in exchange for higher density on the remaining vacant land fell through and the parcel went on the market for $10 million.[7]

After a number of postponements, in March 2008, just hours before the final deadline to demolish the church, a deal was struck with a local community group, whereby they were allowed time to raise money to move the structure. At a cost of some $2 million, the building was reduced to its original appearance and dismantled into pieces, so it could be transported through the narrow, winding streets of the neighborhood. It was reconstructed on the grounds of a cemetery in the nearby neighborhood of Middle Village, where it is now used for community activities.[8]

Relocation

Some Carpenter Gothic buildings have been relocated for reasons ranging from historic preservation to aesthetics. Some, such as All Saints, Jensen Beach, Florida, have been moved only a few hundred feet on the same property in order to get a better view and to allow for expansion, while others such as Holy Apostles, Satellite Beach, Florida, have been barged many miles in order to be preserved. Others such as All Saints, DeQuincy, Louisiana, have been dismantled, transported long distances and then reassembled in order to be preserved and reused. Some structures have been moved many times.

St. Luke's, Cahaba, Alabama, has had an interesting history of moves. In 1876, due to the danger of flooding in Cahaba, it was dismantled and moved from its original location 25 miles or so to Browns where it was reassembled. In 2006–2007, it was carefully dismantled by students from Auburn University and moved back to Cahaba, where it is now being reassembled by the students on the Cahaba State Historic Site not too far from its original location.

Exterior alterations

Some Carpenter Gothic structures such as St. Stephen's in Ridgeway, South Carolina, have had their exteriors altered by stuccoing, brick veneering, etc., so that their original style is no longer apparent.

"American Gothic"

"American Gothic" is a painting by Grant Wood from 1930. Wood's inspiration came from a cottage designed in the Carpenter Gothic style with a distinctive upper window[9] and a decision by the artist to paint the house along with "the kind of people I fancied should live in that house."[10]

Steamboat Gothic

Steamboat Gothic architecture, a term popularized by Frances Parkinson Keyes's novel of that name,[11] is sometimes confused with Carpenter Gothic architecture,[12][13] but Steamboat Gothic usually refers to large houses in the Mississippi and Ohio river valleys that were designed to resemble the steamboats on those rivers.[14]

Recent examples

St. Luke's Church in Blue Ridge, Georgia, was built in 1995.[15] Houses and churches are sometimes built in the Carpenter Gothic style into the 21st Century.

Outside North America

-

Local Catholic church of Konga, Larantuka, Indonesia. (circa 1915).

-

Recreational center of Rio Branco, Brazil, built in 1924.

-

St Mary's Cathedral of Auckland, completed in 1898.

-

St. Mary's Catholic Church of Stanley, Falkland Islands, constructed in 1899.

Many nineteenth-century timber Gothic Revival structures were built in Australia,[16] and in New Zealand - such as Frederick Thatcher's Old St. Paul's, Wellington, and Benjamin Mountfort's St Mary's, but the term "Carpenter's Gothic" is not often used, and many of their architects also built in stone.

Gallery

Churches, synagogues, etc.

-

Emmanuel Episcopal Church, Eastsound, Orcas Island Washington

-

Pioneer Gothic Church, Dwight, Illinois, originally a Presbyterian church

-

Unitarian Universalists of San Mateo, California, California, originally a Methodist church

-

The Old Church (Portland, Oregon), originally Calvary Presbyterian Church

-

St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, Prairieville, Alabama Note the buttresses.

-

La Grange Church, Titusville, Florida, originally non-denominational Protestant

-

St. Mark's Episcopal Church (Palatka, Florida). Note the buttresses at the base of the belfry.

-

Andrews Memorial Chapel (Dunedin, Florida), originally a Presbyterian church

-

Bethany Memorial Chapel (Kendrick, Idaho), originally a Norwegian Lutheran church

-

Tualatin Plains Presbyterian Church, Hillsboro, Oregon

-

St. Paul's Episcopal Church, Lowndesboro, Alabama

-

St. John's-In-The-Prairie Episcopal Church, Forkland, Alabama

-

St. Luke's Episcopal Church, Cahaba, Alabama

-

Gethsemane Evangelical Lutheran Church, Detroit, Michigan

-

St. Agatha's Episcopal Church, DeFuniak Springs, Florida. Note the unusual tower.

-

St. Paul's by-the-sea Protestant Episcopal Church, Ocean City, Maryland

-

Temple Israel, Leadville, Colorado, 1884 Reform synagogue.

Houses

Plain

-

Cottages in a former Methodist camp town in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts on Martha's Vineyard.

-

Another view of cottages in Oak Bluffs,.

-

Peters-Liston-Wintermeier House in Eugene, Oregon

-

Wilson-Durbin House in Salem, Oregon

-

Blydenburgh Farmhouse Cottage, built 1860 in Smithtown, New York

-

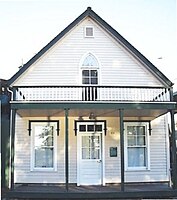

James S. and Jennie M. Cooper House, Independence, Oregon

-

Joseph and Priscilla Craven House, Monmouth, Oregon

Ornate

-

Kingscote in Newport, Rhode Island, built in 1839.

-

Afton Villa, a former plantation house in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. Built from 1848–56, the masonry structure burned in 1963.

-

J. M. Bonney House in Buena Vista, Colorado, built in 1883

-

Eugene Saint Julien Cox House in St. Peter, Minnesota, built in 1871

-

Indian Range, in Davidsonville, Maryland, built in 1852

-

Roseland Cottage, Woodstock, Connecticut

-

Ashe Cottage, Demopolis, Alabama

-

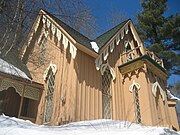

Justin Smith Morrill Homestead Strafford, Vermont

-

Athenwood, Montpelier, Vermont, built 1850

-

Waldwic, Gallion, Alabama

-

J. Mora Moss House in Mosswood Park, Oakland, California

Ornamental use

-

Warren House, Gothic Revival brick house with Carpenter Gothic trim and features, Newburgh, New York, Historic District

See also

- Andrew Jackson Downing

- American Gothic

- Gothic Revival

- Gingerbread (architecture)

- Richard Upjohn

- Springside

- Stick style

- Structure relocation

- United Hebrews of Ocala, a Carpenter Gothic synagogue

- Wedding Cake House (Kennebunkport, Maine). Called the "most photographed building in Maine," it is an example of Carpenter Gothic remodeling of a frame building originally built in another style of architecture.

- Harmony School, School District No. 53 in rural Otoe County, Nebraska is an example of a Carpenter Gothic one-room schoolhouse.

- Images of Revival styles of architecture

References

- ^ The British denigration of Sir George Gilbert Scott's restorations at Ely Cathedral as "Carpenter's Gothic" are discussed in Phillip Lindley, "'Carpenter's Gothic' and Gothic Carpentry: Contrasting Attitudes to the Restoration of the Octagon and Removals of the Choir at Ely Cathedral". Architectural History 30 (1987:83–112).

- ^ What Style Is It?, Poppeliers, et al., National Trust for Historic Preservation

- ^ AGHC: Home Archived June 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Carpenter Gothic". History Colorado. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ Kyles, Shannon. "carpenter". www.ontarioarchitecture.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "The Serious Side of Carpenter Gothic: Why Richard Upjohn Wanted to Build a Country Church in Maspeth - JuniperCivic.com". www.junipercivic.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ WRITER, JOHN LAUINGERDAILY NEWS STAFF. "St. Saviour Church for sale at $10M - NY Daily News". nydailynews.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Angelos, James (April 6, 2008). "For a Church Bathed in History, a Last-Minute Miracle". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Grant Wood" Archived 2011-10-31 at the Wayback Machine, Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ^ Fineman, Mia, The Most Famous Farm Couple in the World: Why American Gothic still fascinates. Archived 2011-09-07 at the Wayback Machine, Slate, 8 June 2005

- ^ Steamboat Gothic by Frances Parkinson Keyes Archived 2011-05-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Steamboat Gothic". pplans.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) See listing number 235, accessed 11-5-2007 - ^ "Definition of STEAMBOAT GOTHIC". www.m-w.com. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "St. Luke's Episcopal Church of Blue Ridge, Georgia - Episcopal Missionary Church". www.stlukesblueridge.org. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Category:Carpenter Gothic churches in Australia - Wikimedia Commons". commons.wikimedia.org. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

External links

- Carpenter Gothic houses

- Bargeboards or vergeboards

- Gothic Revival and Carpenter Gothic in Buffalo

- The serious side of Carpenter Gothic: Richard Upjohn and St. Saviour's Church, Maspeth, Queens, New York

- Website of the C.G. House used by Grant Wood

- Village of Round Lake, New York

- Essential Architecture: Carpenter Gothic