Bart Starr

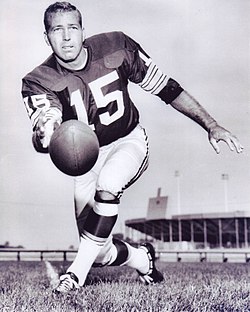

Starr in the 1960s | |||||||||||||||

| No. 15 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position: | Quarterback | ||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||

| Born: | January 9, 1934 Montgomery, Alabama | ||||||||||||||

| Died: | May 26, 2019 (aged 85) Birmingham, Alabama | ||||||||||||||

| Height: | 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) | ||||||||||||||

| Weight: | 193 lb (88 kg) | ||||||||||||||

| Career information | |||||||||||||||

| High school: | Sidney Lanier (Montgomery, Alabama) | ||||||||||||||

| College: | Alabama | ||||||||||||||

| NFL draft: | 1956 / round: 17 / pick: 200 | ||||||||||||||

| Career history | |||||||||||||||

| As a player: | |||||||||||||||

| As a coach: | |||||||||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Career NFL statistics | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Record at Pro Football Reference | |||||||||||||||

Bryan Bartlett Starr (January 9, 1934[1] – May 26, 2019) was a professional American football quarterback and coach. He played college football at the University of Alabama, and was selected by the Green Bay Packers in the 17th round of the 1956 NFL Draft, where he played for them until 1971. Starr is the only quarterback in NFL history to lead a team to three consecutive league championships (1965–1967). He led his team to victories in the first two Super Bowls: I and II.[2] As the Packers' head coach, he was less successful, compiling a 52–76–3 (.408) record from 1975 through 1983.

Starr was named the Most Valuable Player of the first two Super Bowls[2] and during his career earned four Pro Bowl selections. He won the league MVP award in 1966.[3] He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame and the Packers Hall of Fame in 1977. Starr has the highest postseason passer rating (104.8)[4] of any quarterback in NFL history and a postseason record of 9–1.[2] His career completion percentage of 57.4 was an NFL best when he retired in 1972.[5] For 32 years (through the 2003 season), Starr also held the Packers' franchise record for games played (196).[5]

Early life

Starr was born and raised in Montgomery, Alabama to parents Benjamin Bryan Starr (1910–1985), a labor foreman with the state highway department, and Lula (Tucker) Starr (1916–1995).[6] Starr's early life was marked by hardships. Shortly after the start of World War II, his father's reserve unit was activated and in 1942 he was deployed to the Pacific Theater.[7] He was first in the U.S. Army but transferred to the U.S. Air Force[2] for his military career.[8]

Starr had a younger brother, Hilton E. "Bubba" Starr.[9] In 1946, Bubba stepped on a dog bone while playing in the yard and three days later died of tetanus.[10][11] Starr's relationship with his father deteriorated after Hilton's death.[12] He was an introverted child who rarely showed his emotions and his father pushed Starr to develop more of a mean streak.[13]

Starr attended Sidney Lanier High School in Montgomery,[14] and tried out for the football team in his sophomore year, but decided to quit after two weeks. His father gave him the option of playing football or working in the family garden; Starr chose to return to the football field.[15]

In his junior year, the starting quarterback broke his leg and Starr became the starter.[16] He led Lanier to an undefeated season. In his senior season, Starr was named all-state and All-American, and received college scholarship offers from universities across the country.[17] He seriously considered the University of Kentucky, coached by Bear Bryant.[18] Starr's high school sweetheart, Cherry Louise Morton, was planning to attend Auburn and Starr wished to attend a college close to her.[19][20] Starr changed his mind and committed to the University of Alabama.[21]

College career

During Starr’s freshman year at Alabama, the Southeastern Conference allowed freshmen to play varsity football.[22] Starr did not start for Alabama as a freshman, but he did play enough minutes to earn a varsity letter. His high point of the season came in quarterback relief in the Orange Bowl, when he completed 8 of 12 passes for 93 yards and a touchdown against Syracuse.[23]

Starr entered his sophomore year as Alabama's starting quarterback, safety and punter. His punting average of 41.4 yards per kick ranked second in the nation in 1953, behind Zeke Bratkowski.[24] Alabama recorded a 6–2–3 record and lost in the Cotton Bowl to Rice by a score of 28–6. Starr completed 59 of 119 passes for 870 yards, with eight touchdowns that season.

In May 1954, Starr eloped with Cherry Morton.[2] The couple chose to keep their marriage a secret. Colleges often revoked the scholarships of married athletes in the 1950s, believing their focus should remain on sports.[25] Cherry remained in Jackson, Alabama, while Starr returned to the University of Alabama.[25]

That summer, Starr suffered a severe back injury during a hazing incident for his initiation into the A Club. He covered up the cause by fabricating a story about being hurt while punting a football. He rarely played during his junior year due to the injury. The back injury disqualified him later from military service, and would occasionally bother him the rest of his football career. After a disappointing season of 4–5–2, Harold Drew was replaced by Jennings B. Whitworth as coach of Alabama.[26]

Whitworth conducted a youth movement at Alabama for the 1955 season and only two seniors started for the team. Supposedly healed from the back injury, Starr rarely played in his senior season. Starr's decision to play football for Alabama rather than for Bear Bryant at the University of Kentucky did not sit well with Bryant, and four years later as head coach of the Blue–Gray Football Classic in 1955, Bryant hardly let Bart play at all.[27]

Johnny Dee, the basketball coach at Alabama, was a friend of Jack Vainisi, the personnel director of the Green Bay Packers. Dee recommended Starr as a prospect to Vainisi.[28] The Packers were convinced that Starr had the ability to succeed in the NFL and would learn quickly.[29] In the 17th round of the 1956 NFL Draft, Starr was selected by the Packers, with the 200th overall pick.[30][31]

Starr spent the summer of 1956 living with his in-laws and throwing footballs through a tire in their backyard in order to prepare for his rookie season.[32] The Packers offered $6,500 (equal to $72,845 today) to sign Starr and he accepted, with the added condition, requested by Starr, that he receive $1,000 up front.[33]

Packers quarterback

Starr began as a backup to Tobin Rote in 1956 and split time with Babe Parilli until 1959, Vince Lombardi's first year as Packers coach. In that season, Lombardi pulled starter Lamar McHan in favor of Starr, and he held the starting job henceforth. The following season, the Packers advanced to the 1960 NFL Championship Game, but lost to the Philadelphia Eagles in Lombardi's only post-season loss as a head coach.

1961 was Starr's first season as a full-time starting quarterback for the Packers, throwing for over 2,400 yards and 16 touchdown passes, leading the Packers to an 11-3 record and a return to the NFL Championship Game, this time against the New York Giants. Starr threw for 164 yards and 3 touchdowns in a 37-0 Packers victory. Starr and the Packers continued their success in 1962, going 13-1. Even though Starr was not the focal point of the Packers' offense, with the running duo of Jim Taylor and Paul Hornung, he still provided a solid passing attack, throwing for a career-high 2,438 yards and 14 touchdowns, leading the league with a completion percentage of 62.5. The Packers repeated as NFL champions, beating the Giants again in the 1962 NFL Championship game, 16-7. While not as impressive with his passing in the early years of his career, Starr was responsible for calling plays on the Packers' offense (which was then the norm),[34] proving to be an effective strategist on offense.

In 1963, the Packers fell short of qualifying for their fourth consecutive NFL Championship Game appearance, with injuries to Starr keeping him from finishing a few games. Even so, Starr still threw for 1,855 yards and 15 touchdowns. In 1964, with Jim Taylor and Paul Hornung struggling to continue their strong running game, Starr started to become more of the focus of the Packers' offensive attack. Vince Lombardi would help this shift by acquiring more capable pass catchers to the offense, trading for receiver Carroll Dale to join with Boyd Dowler and Max McGee, replacing tight end Ron Kramer with Marv Fleming, and drafting more pass-catching running backs in Elijah Pitts and Donny Anderson. With these new offensive weapons, Starr would put up his best passing seasons from 1964 to 1969. In 1964, despite the Packers only going 8-5-1, Starr threw for 2,144 yards, 15 touchdown passes, and only 4 interceptions. He led the league with a 97.1 passer rating.

In 1965, the Packers went 10-3-1, led by Starr's 2,055 passing yards and 16 touchdown passes, a career-high. The Packers and their Western division foe, the Baltimore Colts, finished the season with identical records, so the two teams met in a playoff game to determine the division winner. Starr was knocked out of the game after the first play when he suffered a rib injury from a hard hit, but the Packers managed to win in overtime, 13-10, led by Starr's backup, Zeke Bratkowski. Starr came back and started the 1965 NFL Championship Game against the Cleveland Browns. On a sloppy Lambeau field, the Packers went back to their classic backfield tandem of Taylor and Hornung, with the pair running for over 200 yards. Starr threw for only 147 yards, but that included a 47-yard touchdown pass to Carroll Dale.

In 1966, Starr had arguably the best season of his career, throwing for 2,257 yards, 14 touchdown passes, and only 3 interceptions. He led the NFL with a completion percentage of 62.2 and a 105 passer rating, while leading the Packers to a dominating 12-2 record. Starr would be named the NFL's Most Valuable Player by the Associated Press (AP),[35] the Sporting News,[36] the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA),[37][38] and the UPI[39] In the NFL Championship Game against the Dallas Cowboys, Starr had his best postseason performance, throwing for 304 yards and 4 touchdown passes, leading the Packers to a 34-27 victory, and the right to represent the NFL in the first ever Super Bowl, against the AFL champion Kansas City Chiefs. Starr had another solid game against the Chiefs, throwing for 250 yards and two touchdowns, both to Max McGee, in a decisive 35-10 Packers win. Starr was named the first-ever Super Bowl MVP for his performance.

1967 was a down year for Starr, especially when compared to his previous three seasons. Bothered by a hand injury for much of the season, Starr threw for only 1,823 yards and 9 touchdowns, with a career-high 17 interceptions thrown. Helped in large part by their defense, the Packers still finished 9-4-1, which was good enough for the Packers to reach the postseason. In the divisional playoff against the Los Angeles Rams, Starr was back in form, throwing for 222 yards and a touchdown pass in a 28-7 Packers triumph. This victory would set the stage for the infamous Ice Bowl against the Dallas Cowboys in the 1967 NFL Championship Game. Consulting with Lombardi on the sideline, Starr suggested a basic wedge play ― with a twist. Instead of handing off to Chuck Mercein as the play dictated (and unbeknownst to his teammates), Starr suggested running it in himself. Having enough of the bitterly cold weather, Lombardi said, “Then do it, and let's get the hell out of here!" Starr almost broke down in laughter as he ran back to the huddle, but held his composure. The quarterback sneak play worked and the Packers went on to beat the Cowboys 21-17.[2] Even in the cold conditions, Starr was still able to throw for 191 yards in the Ice Bowl, with two touchdown passes to Boyd Dowler.

At the Orange Bowl in Miami, the Packers defeated the AFL champion Oakland Raiders 33–14 in Super Bowl II, Lombardi's final game as head coach of the Packers.[40] Starr won his second consecutive Super Bowl MVP award for his performance, where he threw for 202 yards and a touchdown pass, a 62-yard strike to Boyd Dowler. The 1967 Packers remain the only team to win a third consecutive NFL title since the playoff system was instituted in 1933.

Starr had originally planned to retire after the second Super Bowl win in January 1968, but without a clear successor and a new head coach, he stayed on. After Lombardi's departure, Starr continued to be a productive quarterback under new Packers coach Phil Bengston, though injuries hampered him. Starr threw for 15 touchdown passes in 1968, leading the NFL once again in completion percentage (63.7) and passer rating (104.3). Starr

- ^ "UPI Almanac for Thursday, Jan. 9, 2020". United Press International. January 9, 2020. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

…football Hall of Fame member Bart Starr in 1934

- ^ a b c d e f Layden, Tim (May 26, 2019). "Bart Starr: The Self-Made QB Who Led Lombardi's Packers". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved May 27, 2019.

- ^ Profootball Hall of fame – Bart Starr

- ^ "NFL Passer Rating Career Playoffs Leaders". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Packers.com

- ^ Christopulos, Mike (December 25, 1974). "Open door policy pleases Bart's dad". Milwaukee Sentinel. p. 2, part 2. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ Starr, by Bart Starr, pg. 15

- ^ Mooney, Loren (October 12, 1998). "Bart Starr, Green Bay Packers Legend". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on March 12, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ Butterball 2004 pg. 19–20

- ^ Starr, by Bart Starr, pg 17

- ^ Claerbaut 2004 pg. 21

- ^ Claerbaut 2004 pg. 23

- ^ Starr, by Bart Starr, pg 18

- ^ Claerbaut 2004 pg. 24–25

- ^ Starr, by Bart Starr, pg 21

- ^ Claerbaut 2004 pg. 27–28

- ^ Claerbaut 2004 pg. 32

- ^ Bart Starr by John Delaney, pg 32

- ^ Starr, by Bart Starr, pg 25

- ^ Claerbaut 2004 pg. 34–35

- ^ Claerbaut 2004 pg. 35–36

- ^ Bart Starr, by John Devaney, pg. 34

- ^ Bart Starr, by John Devaney, pg. 36

- ^ Bart Starr, by John Devaney, pg. 38

- ^ a b Starr, by Bart Starr, pg 26

- ^ Goodman, Joseph (February 29, 2016). "NFL legend Bart Starr was victim of 'brutal' secret Alabama hazing". al.com. Archived from the original on February 29, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Ed (June 1, 2019). "A Starr Has Fallen". The Alabama Gazette. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ Starr, by Bart Starr, pg 29

- ^ Bart Starr, by John Devaney, pg. 40

- ^ "Bart Starr at ProFootballHOF.com". profootballhof.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- ^ Claerbaut 2004 pg. 47–48

- ^ Bart Starr, by John Devaney, pg. 42

- ^ Claerbaut 2004 pg. 49–50

- ^ "Bart Starr is Clearly Underrated". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ^ Hand, Jack (December 15, 1966). "Bart Starr Most Valuable Player". The Morning Record. Associated Press. p. 9. Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "TSN Player of the Year". Archived from the original on July 16, 2009.

- ^ Olderman, Murray (December 22, 1966). "Bart Starr Is Selected Jim Thorpe Award Winner". Standard-Speaker. Newspaper Enterprise Association. p. 25. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Newspaper Ent. Assoc. NFL Most Valuable Player Winners". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ Total Football II: The Official Encyclopedia of the National Football League. Bob Carroll. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 9780062701749 pg. 389.

- ^ "Super Bowl History". VegasInsider.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2019.