P&O dismissal controversy

On 17 March 2022, shipping company P&O Ferries dismissed 800 members of its shipping staff, primarily from the Port of Dover, but also from Kingston upon Hull, Liverpool and Cairnryan. The decision was greeted with much criticism from both sides of the political divide, particularly as a result of the speed and immediacy of the crews' termination notices, which in some cases consisted of a video call or text message, terminating their employment "with immediate effect". Also of concern was the fact that the crews were intended to be replaced with cheaper agency labour. The two main trades unions involved—the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT) and Nautilus International—called for a boycott of the company and organised protests around the ports, but also outside parliament. P&O explained that for some time their business model had been impractical, making them losses of £100 million per annum and that they needed to drastically reduce the wage bill to become profitable. Conversely, critics argued that the parent company, DP World, had paid out large dividends the previous year, and also claimed under the UK government's furlough scheme during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The British government criticised the company's actions and stated that it was looking at the legal ramifications, including whether P&O could be fined, and how other contracts it held with DP World were affected. The legal community was generally critical of P&O for seemingly ignoring UK employment law, and several law firms commented on the likelihood of any crew members' potential employment tribunal claim being successful on a number of grounds. For its part, P&O argued that to have followed the suggested consultation and other processes would have caused even more trauma to both their own staff and the broader UK tourist industry.

Background

P&O Ferries was originally a subsidiary of the shipping company P&O, which was founded in 1837 as the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, sailing between the UK, Iberia and Egypt, and by 1922, Australia.[1] P&O began operating ferry services in the 1960s and in 2002 amalgamated their various ferry lines into one company, P&O Ferries.[2] By 2020, P&O Ferries had become a leading UK ferry operator with business worth around £10 million per annum, and a 15% share of maritime freight transport before the pandemic.[3]

The company received £15 million in grants, including furlough payments during the COVID-inspired slump,[3] although the company announced 1,100 job cuts soon after.[4] It is owned by Dubai-based DP World, a multinational shipping and logistics company[3] owned by the UAE government.[5] The BBC noted that DP World had paid dividends to its shareholders of £270 million in 2020.[3]

In 2020, P&O employed around 1700 seafarers.[6] P&O had previously closed routes—for example, two between Hull to Zeebrugge—and put them up for sale in February 2021. The company said the routes were loss-making, and the government stated that this was a commercial matter.[7] Also reduced as a result of the pandemic were the number of Dover–Calais runs, and two freight services were cancelled.[8]

Dismissals

On 17 March 2022, shipping company P&O dismissed 800 members of its shipping staff, including officers and ratings.[1] The bulk of these—approximately 500—were in Dover.[9] Staff were informed via what one staff member described as a "three-minute pre-recorded"[3] video call the same day that their employment was "terminated with immediate effect due to redundancy".[3] Other reports suggested that staff were given a short period of time to disembark.[1] P&O stated that only a minority—261—of the affected workers had received their notice in this fashion. The majority had face to face meetings with their local management, although in some cases SMS, a phone call or email was used. A spokesman said that "we know that for our staff this redundancy came without warning or prior consultation, and we fully understand that this has caused distress for them and their families".[10] A letter from the company to the redundant staff suggested that if any of the latter "were affected by [the news] then please do take some time to absorb it".[9]

Some staff occupied their ships, although they were later removed.[3] They were backed by both RMT and Nautilus International.[11] P&O prepared in advance for physical force intervention and recruited "handcuff-trained" security guards for the Dover terminal two days before the announcement.[3] However, the company denied that the guards wore balaclavas[10] and argued that "the teams escorting the seafarers off our vessels were totally professional in handling this difficult task with all appropriate sensitivity. Contrary to rumours, none of our people wore balaclavas nor were they directed to use handcuffs nor force."[12]

P&O suspended ferry services while they located cheaper agency workers for the Dover to Calais, Larne to Cairnryan, Dublin to Liverpool and Hull to Rotterdam routes.[3] The firm intended to use the International Ferry Management agency, and this was revealed in a letter from chief executive Peter Hebblethwaite, which was leaked to the Daily Mirror.[13] Some reports suggested that the cheaper labour the company was investing in would be by using foreign workers.[1]

The Evening Standard reported that Dover was in "chaos" on Thursday night, with roads gridlocked by cars and lorries attempting to leave and enter the port.[14] Passengers at Dover were advised to use DFDS services until P&O were in a position to restore theirs;[3] those for Dublin were pointed to Stena Line services. Many passengers, though, were stranded; many complained at the lack of information from the company.[15] Stena reported that as P&O had not approached them with an agreement, tickets could not be honoured and those wishing to travel on Stena would have to be new passengers.[16]

Criticism

The company acknowledged the "distress" it said its employees had experienced,[12] but said it had had to make a "tough" decision, in order to enact "swift and significant changes" which were a necessity if it was to maintain business viability.[3] A statement said that they had made a loss of £100 million which had been covered by its umbrella company, DP World, and that "This is not sustainable. Without these changes there is no future for P&O Ferries",[3] and that "the business wouldn't survive without fundamentally changed crewing arrangements".[17] The changes were intended to reduce crewing costs by 50%, the CEO subsequently said.[9]

At 11am ratings and officers were informed there was going to be a pre-recorded Zoom meeting. After that two to three-minute call, all the crew were made redundant. I've seen grown men crying on there because they don't know where they're going to go from today[3]

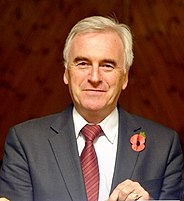

A number of the agency workers—among them former P&O staff[18]—hired to replace the crews in Hull walked off the job. One, Mark Canet-Baldwin, arrived at Cairnryan only to turn around. He told reporters, "I felt I can't do it. I felt sick to my stomach. And I walked off. Two others came with me. It's just wrong."[3] P&O's actions attracted cross-party criticism.[12] In Dover, Elphicke marched alongside the RMT's General Secretary and senior assistant general secretary, as well as the former shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, which a Channel 4 report described as "unlikely bedfellows".[9] A government statement described the mass dismissal as "wholly unacceptable". The parliamentary undersecretary for transport, Robert Courts said "reports of workers being given zero notice and escorted off their ships... shows the insensitive way in which P&O have approached this issue", and that he was "extremely concerned and frankly angry at the way workers have been treated by P&O".[3] It was, however, unlikely that the government would support nationalising the company, stated Dowden.[12]

Huw Merriman, chair of the House of Commons transport select committee expressed concerns as to the legality of the company's actions, and told the government to "ensure that this appalling employment transaction cannot be completed".[19] The Department for Transport reported that neither Courts, nor the Secretary of state, Grant Shapps, had had prior warning of the company's intentions.[3] However, by Friday it was reported that, in fact, the government had learned of P&O's plans on Wednesday night. A Downing Street spokesman reported that, while the DfT's senior officials had been informed, they had restricted propagation on commercial sensitivity grounds, and this had included the Prime Minister.[5] He also did not think it had come up for discussion when the PM visited the United Arab Emirates the previous Wednesday.[5] Shapps later said that, while he had been made aware of the plan on Wednesday evening, he had assumed it would involve the same in-depth consultation as the previous layoffs.[20]

We expect companies to treat their employees fairly. It is only in extreme circumstances that employers need to make extreme decisions to secure the future of their businesses if all other avenues have failed, including negotiations between employer and employees. We don’t believe this was the case for P&O staff. We are looking into this very carefully.[5]

— Number 10 spokesman

The staff's trade union, the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers said it was one of the "most shameful acts in the history of British industrial relations".[3] The union asked that the government use influence to pressure a reversal of the decision, while there were broader calls for DP World to be excluded from bidding for any future free ports.[5][note 1] Manuel Cortes of the Transport Salaried Staffs Association said the company "should be ashamed of themselves".[19]

The TUC General Secretary, Frances O'Grady said it was "reprehensible" to sack staff with no notice period.[3] She also demanded the P&O "suffer severe consequences—with ministers increasing the legal penalties if necessary".[11] The Mayor of Manchester, Andy Burnham, called the company's strategy a "gangster practice",[13] while a member of Medway Council called on golfer Ian Poulter to sever his ties with DP World, for whom he acted as an ambassador.[13] The head of the European Transport Workers' Federation in Brussels, Livia Spera, said it was "astonishing that this can happen in a major developed country like the UK".[15] In Northern Ireland, Democratic Unionist Party politicians called on the government to maintain services between Larne to Cairnryan, while Nicola Sturgeon expressed "utter disgust" at the dismissals.[6]

Staff observed that the timing seemed odd, noting that while it was the sort of thing that happened at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, travel restrictions were lifting around Europe and the busy Summer period was approaching.[3] Another member of staff queried why the company had been "ordering new uniforms and giving us all a pay rise" a few days earlier.[18]

Ruston Tata of DMH Stallard, suggested that P&O's public image would suffer as a result of the public perceiving their premeditated plan as an over the top reaction.[3] Likewise, Ann Francke, head of the Chartered Management Institute, bluntly stated that the company had "got it very wrong" and described their management practices as being from "another era"[3] Conservative Party co-chair, Oliver Dowden commented that he felt, "frankly, a revulsion at the kind of sharp practices from P&O. There has been a complete lack of engagement, a lack of prior notice or indeed any empathy whatsoever for the workers."[17] Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury in a joint statement with Rose Hudson-Wilkin, the Bishop of Dovery, said "ill-treating workers is not just business. In God’s eyes, it is sin." They also suggested that P&O's timing was intended to take advantage of the distraction provided by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[10]

RMT complained that, while they requested talks with the company, they had heard nothing from P&O, even though the union believed that the cuts must have taken a long time planning.[note 2] RMT also argued that, if the company was in financial trouble, this was due to it having "been financially mismanaged for years".[18] The union called for a mass boycott of P&O; this was backed by Opposition MPs including Karl Turner, of East Hull and Louise Haigh, the shadow transport secretary. Turner argued that the government should reclaim the furlough money it had paid previously,[17] while Haigh suggested P&P have its licence to operate withdrawn and remove the company from the transport advisory group.[5] Turner, along with fellow Hull MPs Emma Hardy and Diana Johnson, also called for the renaming of the Pride of Hull.[22] The Minister of Defence James Heappey, also backed the recouping of P&O's furlough money,[5] although Channel 4 understood this to be not a likely proposition.[9] RMT general secretary Mick Lynch said the union would be presenting an action plan to the government. Mark Dickinson, of Nautilus, described the sackings as "a new low".[5]

Matthew Lynn, writing in The Telegraph, meanwhile, argued that[23]

It would be easy to criticise P&O, and even more its parent company Dubai World, for that decision. In fairness, it has handled the process with spectacular crassness. And yet the militants of the RMT Union are just as much to blame as the bosses. He suggested that P&O's move was "probably the most dramatic piece of union-busting since Rupert Murdoch moved all his newspaper titles from Fleet Street to Wapping in 1986."

Protests

The RMT instructed members to occupy the ships they were on to prevent them from being locked out after they disembarked.[14] In Hull, the crew of the Pride of Hull lifted the gangway of their vessel, preventing security guards[3] and police[1] from boarding, although later left the ship of their own accord. The ship's full time union representative, Gary Jackson told the BBC that the crew were "devastated".[3] He praised the ship's captain for raising the gangway as he had, which he suggested was for the crew's safety: he suggested that the hired security would have pulled them off if they could have. Other workers, not employed by P&O, were also trapped on board; one complained of false imprisonment by the captain. The crew members eventually left the ship approximately five hours later in response to P&O agreeing to provide RMT with the documentation the union required.[18] DP World's London offices were picketed.[13]

Protests took place the following day, Friday 18 March, in Hull, Liverpool and Dover.[18] Former Labour leader Ed Miliband attended, as did the leader of the Labour council, Darren Hale, who talked about the damage the job losses would do to the city as well as the wider precarity within the industry. He argued that Brexit was partly to blame, as it had been intimated that the country would no longer be bound by European employment practices.[13] In Dover protestors gathered outside the RMT's regional office[24] and then marched on the terminal, blocking roads[18] when it was suspected that approaching buses contained strikebreakers.[24] Protesters shouted "seize the ships" as they marched.[25] Kent police were in attendance.[26] In Liverpool, protests took place outside the Conservative Party's spring conference for its first day.[17] Dover MP Natalie Elphicke joined the protest,[10] although it was reported that she was "barracked" by some protestors on the grounds that she had voted for fire and rehire in parliament the previous year. However, Elphicke blamed bad business practices rather than government policy before leaving,[13] and condemned the job losses as a "u-turn" on assurances the company had previously made to her.[24] She said, following previous restructurings, the current arrangement she had brokered with the RMT had been intended to ensure the long-term survival of the Dover workforce.[27] Protestors claiming that Conservative anti-trades union legislation permitted behaviour such as that exhibited by P&O.

Later events

Services from Liverpool to Dublin, using the Norbank, had been restored by the afternoon of 19 March, although with what crew was unknown.[17] The company stated that it was losing £1 million each day its ships were docked.[10] The Labour Party called upon the government to block the route pending resolution of the dispute, and the government confirmed it was reviewing its contracts with the company;[17] Shapps instructed the Maritime and Coastguard Agency to carry out official inspections of all P&O ships docked in British waters, particularly with regard to the training and diligence of the crews.[17] The Guardian suggested that the affair was likely to focus attention on the practice of hiring/refiring, and particularly on attempts to outlaw it.[10]

French news reported that, while P&O maintained a staff of around 250 persons in Calais, no French staff had been dismissed,[28] although it was agreed that the news would "shake up" the cross channel market.[29] Scottish ferry firm Caledonian MacBrayne released a statement supporting the P&O workers and offering employment for whoever could take it. The company, known as CalMac, had 16 deck ratings and one purser's position available at the time.[30]

The BBC reported union claims that the replacement crews from India were being paid "as little as £1.80 an hour" on the Dover–Calais route. The minimum wage in the UK is £8.91 an hour, but this does not apply to ships that sail through international waters, or that are flagged outside the UK. Some of P&O's ships were flagged to Cyprus after Brexit. The BBC also said that while P&O disputed this figure, it was unable to discuss wages paid by a third-party employer.[20]

On 24 March Shapps wrote to Hebblethwaite to give him "one final opportunity" to reinstate the 800 workers.[31] On 29 March Hebblethwaite said he would not resign, despite two of the company’s vessels being impounded over safety concerns and said that the company would not reinstate the 800 workers it sacked.[32]

Legality

The company's position was a form of fire and rehire. This is an employment practice whereby a company dismisses staff but encourages them to reapply for their old jobs under less favourable employment rights. P&O's version of the procedure was different, suggested The Guardian, as they were sacking employees, replacing them with agency staff and apparently encouraging the sacked staff to join those agencies.[11] A government spokesperson said it would be "dismayed" if P&O were using fire and rehire practices, although the paper wrote that the government had not banned the practice when it had had the opportunity.[11][note 3] The government received legal advice on P&O's actions, although it was not immediately released publicly.[17]

However, the company appeared to have committed the statutory requirement to consult with staff before the process begins.[11] The legality of P&O's actions has been questioned in a number of quarters. Nathan Donaldson, an employment solicitor with Keystone Law, said that while there was precedent, "it is exceptional to forego appropriate notice and consultation processes".[3] The company suggested that they had declined to consult before the dismissals on the grounds that that would have created the same level of disruption to both the company and UK trade generally.[10]

Donaldson noted that, while the government had reviewed the law surrounding the practice the previous year, its report had emphasised it was expected to be used as a measure of last, rather than a first, resort.[3] Rustom Tata also believed that staff either sacked, or about to be, would almost certainly have a claim of unfair dismissal, and queried why the company appeared to have "wholly ignored" relevant aspects of the law, suggesting that the company appeared to be "effectively seeking to avoid having to renegotiate terms with staff and their representatives".[11] Beth Hale, of CM Murray suggested that the company's directors could themselves be criminally liable.[5] Tata also noted though that the sit-ins and staff occupation of the company's vessels could have a negative impact on a tribunal claim, as P&O could counterclaim for losses incurred and thus reduce the amount of compensation individual employees received.[11]

Under UK law—specifically the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992—companies wishing to make over 100 redundancies are obligated to inform the business secretary, Kwasi Kwarteng, 45 days beforehand; a spokesman for the Prime Minister confirmed on Thursday afternoon that no such notice had been received.[11] The Guardian reported that employment lawyers had reacted "with surprise" to the news, with some suggesting that the company may have broken several laws and leaving them liable to unfair dismissal claims at employment tribunals. Kathryn Evans of Trethowans, for example, suggested "staff could end up being paid 'hundreds of thousands of pounds in failure to consult and unfair dismissal awards'".[11] On Friday Kwarteng also advised that he was looking into fining P&O—up to a potentially limitless amount—if the company's actions were found to be illegal. In a letter to P&O, he argued that "it cannot be right that the company feels tied closely enough to the UK to receive significant amounts of taxpayer money but does not appear willing to abide by the rules that we have put in place to protect British workers".[10] He warned the company of "ramifications" should it be found to have broken the law.[27][note 4]

By the evening of Thursday, suggested The Guardian, P&O may have "recognised the unlawfulness of its actions", as it appeared to be willing to issue "enhanced" redundancy packages.[11] The following Monday, it emerged that these packages required signing a non-disclosure agreement.[20] Thompsons Solicitors was instructed by RMT to act on behalf of the sacked workers. Neil Todd, speaking from Thompson's, confirmed their belief that employment law regarding consultation and notification did not appear to have been carried out, and also dismissed P&O's claim that it was the fault of COVID-19 as "beyond cynical" when compared to the diligence with which they applied for furlough assistance.[14]

Relevance of Brexit

The Guardian argued that, superficially, the first major swathe of job losses since Brexit was its "first big test of workers' rights".[34] Haroon Siddique, the legal affairs correspondent, noted that when he was campaigning to leave the EU, the Prime Minister had suggested that workers' rights would improve as a direct result. Siddique also wrote that Britain was in any case unable to lower rights to below those that existed on 30 December 2020, and that, indeed, there had been no attempt by the government to do so. Interviewed, John Bowers of Brasenose College stated that, while redundancy law operated under UK statute, the necessity of a consultation period was an unaltered remnant of European law. Conversely, however, Andrea London of Winckworth Sherwood, described Brexit as a "red herring", and that the spirit of the requirement to consult went back far longer in English law than its European counterpart.[34] Siddique concludes that the main area where Brexit might make a difference is legally. Previously, if a case had gone to the Supreme Court it could be appealed to the European Court of Justice if a case came within its purview. In the event that the P&O redundancy tribunals remained a simple affair of breaches of the UK's own employment law, then the cases were unlikely to even get to the Supreme Court, making an appeal to the Court of Justice moot.[34]

A number of factors were probably at play, including rising fuel costs and the disruption of travel, with its increased paperwork, following Brexit, and Covid. For its part, DP World said it had never received a dividend from the ferry business.[15]

Notes

- ^ DP World is lined up to be a major operator at the Solent and Thames freeports, "putting DP World firmly in the slipstream of post-Brexit government economic policy", argues Gwyn Topham of The Guardian.[21]

- ^ Simon Calder of the Independent also described P&O's plan as "carefully laid".[16]

- ^ A private member's bill was filibustered in October 2021 by junior business minister Paul Scully, who spoke for long enough to ensure the bill used up its allotted time. Opposition MPs called the decision "cowardly", while Scully argued that legislation was an inappropriate method of dealing with it. He said, "the unambiguous message is that bully-boy tactics of fire-and-rehire, for use as a negotiating tactic, is absolutely inappropriate" in the view of his government.[33]

- ^ Kwarteng addressed his letter to Robert Woods, chairman of P&O, although in the event it transpired that Woods had resigned in December 2021; civil servants said that the error was due to DP World's website being out of date.[10] Woods joined the board of DP World.[27]

References

- ^ a b c d e Sommerlad 2022.

- ^ "About P&O Ferries". P&O Heritage. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Martin 2022.

- ^ BBC Kent 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Topham, Stewart & Sweney 2022.

- ^ a b Oliver et al. 2022.

- ^ BBC Humberside 2021.

- ^ BBC UK 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Jenne 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stewart, Topham & Weaver 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Davies 2022.

- ^ a b c d Coffey et al. 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Weaver 2022.

- ^ a b c Keane & Davis 2022.

- ^ a b c Topham 2 2022.

- ^ a b Calder 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Murray 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Lee & Timmins 2022.

- ^ a b Jones 2022.

- ^ a b c Topham 3 2022.

- ^ Topham 2022.

- ^ BBC Humberside 2022.

- ^ Lynn 2022.

- ^ a b c BBC Southeast 2022.

- ^ ITV 2022.

- ^ Hennessey 2022.

- ^ a b c Hayes & Enokido-Lineham 2022.

- ^ Myszka 2022.

- ^ Darriet 2022.

- ^ Brawn 2022.

- ^ Evans, Eva (24 March 2022). "P&O Ferries: Transport Secretary tells boss to reinstate 800 sacked workers". JOE.co.uk. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Clatworthy, Ben (29 March 2022). "Defiant P&O Ferries chief refuses to rehire sacked workers or quit". The Times. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Walker 2021.

- ^ a b c Siddique 2022.

Sources

- BBC Humberside (2021-02-18). "Former Hull to Zeebrugge ferries for sale after route closes". BBC News. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- BBC Humberside (2022-03-17). "Sacked P&O Hull ferry crew leave ship after protest". BBC News. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- BBC Southeast (2022-03-17). "P&O job losses devastating blow for Dover, local MP says". BBC News. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- BBC Kent (2020-05-12). "P&O ferry operator job cuts 'followed government support'". BBC News. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- BBC UK (2020-10-01). "P&O to axe Hull to Zeebrugge route due to Covid impact". BBC News. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- Brawn, S. (2022-03-18). "'We have vacancies': CalMac in message of support to sacked P&O staff". The National. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Calder, S. (2022-03-17). "P&O Ferries defends brutal sacking of 800 staff". The Independent. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Coffey, H.; Calder, S.; Thackray, L.; Dalton, J. (2022-03-18). "P&O Ferries: Firm 'aims to have services up and running in a day or two'". The Independent. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Darriet, M. (2022-03-17). "Transmanche : P&O licencie 800 marins britanniques, à Douvres". France Bleu (in French). Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- Davies, R. (2022-03-17). "What are the legal implications of P&O Ferries sacking 800 staff?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- Hayes, A.; Enokido-Lineham, O. (2022-03-21). "P&O Ferries defends 'last resort' decision to sack 800 staff on the spot". Sky News.

- Hennessey, T. (2022-03-17). "P&O workers block road to Port of Dover in jobs protest". The Independent. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ITV (2022-03-18). "Ferry operator P&O 'exploiting every loophole' after sacking staff". ITV News. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Jenne, A. (2022-03-18). "P&O Ferries: Political unity after company sacks 800". Channel 4 News. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Jones, A. (2022-03-17). "Unions threaten legal action over 'shameful' sacking of P&O workers". The Independent. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Keane, D.; Davis, B. (2022-03-17). "Lorries and passengers stranded at Dover as P&O Ferries sack 800 staff". www.standard.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Lee, J.; Timmins, B. (2022-03-17). "P&O Ferries: 'We've been abandoned by the company', say sacked staff". BBC News. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- Lynn, M. (2022-03-17). "Unions are as much to blame as P&O bosses for the ferries chaos". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Martin, J. (2022-03-18). "Outrage and no ferries after mass P&O sackings". BBC News. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- Murray, J. (2022-03-19). "P&O resumes Liverpool-Dublin service as government reviews contracts". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- Myszka, D. (2022-03-17). "Transmanche : P&O Ferries à l'arrêt, 800 marins britanniques licenciés". La Voix du Nord (in French). Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- Oliver, M.; Gill, O.; Ashworth, L.; Gartside, B.; Bottaro, G. (2022-03-17). "Downing Street hits out at 'fire and rehire' by P&O Ferries after it sacks 800 staff". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Siddique, H. (2022-03-18). "Are the P&O Ferries mass sackings a result of Brexit?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- Sommerlad, J. (2022-03-18). "Who owns P&O and why has it sacked its UK staff?". The Independent. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Stewart, H.; Topham, G.; Weaver, M. (2022-03-18). "P&O Ferries told it could face unlimited fine if sackings unlawful". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- Topham, G. (2022-03-18). "DP World's controversial history of P&O ownership". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- Topham 2, G. (2022-03-17). "P&O Ferries sacks all 800 crew members across entire fleet". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Topham 3, G. (2022-03-21). "Replacements for P&O Ferries crew paid £1.80 an hour, unions say". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Topham, G.; Stewart, H.; Sweney, M. (2022-03-18). "Government knew of P&O Ferries sackings the day before, No 10 admits". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- Walker, P. (2021-10-22). "Anger as ministers block 'fire and rehire' bill in Commons". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- Weaver, M. (2022-03-18). "Angry protests against P&O Ferries take place at ports across UK". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-20.