Suspended chord

| Component intervals from root | |

|---|---|

| perfect fifth | |

| perfect fourth | |

| root | |

| Tuning | |

| 6:8:9 | |

| Forte no. / | |

| 3-9 / |

| Component intervals from root | |

|---|---|

| perfect fifth | |

| major second | |

| root | |

| Tuning | |

| 8:9:12 | |

| Forte no. / | |

| 3-9 / |

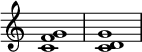

A suspended chord (or sus chord) is a musical chord in which the (major or minor) third is omitted and replaced with a perfect fourth or a major second.[1] The lack of a minor or a major third in the chord creates an open sound, while the dissonance between the fourth and fifth or second and root creates tension. When using popular-music symbols, they are indicated by the symbols "sus4" and "sus2".[2] For example, the suspended fourth and second chords built on C (C–E–G), written as Csus4 and Csus2, have pitches C–F–G and C–D–G, respectively.

Suspended fourth and second chords can be represented by the integer notation {0, 5, 7} and {0, 2, 7}, respectively.

Analysis

The term is borrowed from the contrapuntal technique of suspension, where a note from a previous chord is carried over to the next chord, and then resolved down to the third or tonic, suspending a note from the previous chord. However, in modern usage the term concerns only the notes played at a given time – the suspended tone does not necessarily resolve and is not necessarily "prepared" (i.e., held over) from the prior chord. As such, after Csus4 (C–F–G), F may resolve to E (or E♭, in the case of C minor), but in rock and popular music the term indicates only the harmonic structure with no implications about what comes before or after, though preparation of the fourth still occurs about half the time and traditional resolution of the fourth occurs usually.[3] In modern jazz, a third can be added to the chord voicing, as long as it is above the fourth.[4][failed verification]

Each suspended chord has two inversions. Suspended second chords are inversions of suspended fourth chords, and vice versa. For example, Gsus2 (G–A–D) is the first inversion of Dsus4 (D–G–A) which is the second inversion of Gsus2 (G–A–D). The sus2 and sus4 chords both have inversions that create quartal and quintal chords (A–D–G, G–D–A) with two stacked perfect fourths or perfect fifths.

Sevenths on suspended chords are "virtually always minor sevenths" (7sus4), while the 9sus4 chord is similar to an eleventh chord and may be notated as such.[3] For example, C9sus4 (C–F–G–B♭–D) may be notated C11 (C–G–B♭–D–F).

Jazz sus chord

A jazz sus chord[4] or 9sus4 chord is a dominant ninth chord with a suspended fourth, typically appearing on the dominant 5th degree of a major key. Functionally, it can be written as V9sus4. For example, the jazz sus chord built on C, written as C9sus4 has pitches C–F–G–B♭–D.

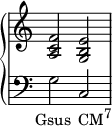

Compared to the otherwise similar dominant eleventh chord, the dominant 9sus4 chord generally doesn't include the third factor. It may be thought of as a slash chord: G9sus4 without the 5th (G–C–F–A) is equivalent to F/G (G–F–A–C).[4][5] It may also be written Dm7/G, which shows the merging of ii7 and V7 functions in one chord.[4][6] Although the suspended fourth is not always resolved down to a third, the note is still not usually notated as an eleventh because of the chord's function as a cadence point to the tonic.

It is also possible to have the third included in a sus chord, the third being generally voiced above the fourth (i.e. as a tenth) though this is not absolutely necessary. For example, a G9sus4 chord played on a piano could have its root note played with the left hand, and the notes (from the bottom up) C (suspended 4th), F, A, and B (the third) with the right hand.[7]

Red Garland's piano introduction to "Bye Bye Blackbird" on the Miles Davis album 'Round About Midnight features suspended 9th chords.[8] In his book Thinking in Jazz, Paul Berliner writes at length and in detail about how the improvisation unfolds from this opening.[9]

With the advent of modal jazz in the 1960s, suspended chords were to feature with increasing regularity. For example, they dominate the structure of Herbie Hancock's 1965 composition "Maiden Voyage". In his book, What to Listen For in Jazz, Barry Kernfeld cites Hancock's own explanation of how the harmony works: "You start with a 7th chord with the 11th on the bottom—a 7th chord with a suspended 4th—and then that chord moves up a minor third. ... It doesn't have any cadences; it just keeps moving around in a circle."[10] Kernfeld comments: "Thus in addition to a slow-paced harmonic rhythm, this composition features chords that individually and collectively avoid a strong sense of tonal function." Kernfeld admires the way that "Hancock's cleverly ambiguous chords intentionally obscure the identity" of a particular key.[10] Roger Scruton sees the jazz sus chord in "Maiden Voyage" as opening "a completely new harmonic perspective... as we come to understand sus chords on the tonic as supporting improvisations on the dominant."[11]

Examples in popular music

Suspended chords are commonly found in folk music and popular music. Ian MacDonald writes of the "heartbreaking suspensions" that characterise the harmony of "The Long and Winding Road" from the Beatles' final album Let It Be (1970).[12] MacDonald describes another Beatles song "Yes It Is" as having "rich and unusual harmonic motion" through its use of suspensions.[13] Joni Mitchell was perhaps one of the most prolific songwriters to make extensive use of multiple sus chords, explaining that "so much in my life was unresolved from 'when were they going to drop the big one?' to 'where is my daughter?' that I had to use unresolved chords to convey my unresolved questions".[14]

Burt Bacharach's "The Look of Love" in the arrangement performed by Dusty Springfield (1967) opens with a clearly audible Dm7 suspension.[15] Carole King's song "I Feel the Earth Move" from her album Tapestry (1971) features a striking B♭sus9 chord at the end of the phrase "mellow as the month of May".[16] The last chord of the first bridge of The Police's "Every Breath You Take" is an unresolved suspended chord,[3] the introduction and chorus of Shocking Blue's "Venus" each contain an unresolved suspended chord,[3] and the introduction of Chicago's "Make Me Smile" has two different suspended chords without traditional resolution.[3]

Examples in classical music

Examples of suspended chords can be found in the pieces below (usually in connection with pedal points).

Debussy's "Golliwogg's Cake Walk" from his Children's Corner suite for piano (1908):

The piano postlude to the song "Ich grolle nicht" from Robert Schumann's 1844 song cycle Dichterliebe.

The concluding bars of the Prelude to Wagner's final opera Parsifal (1882):

The first movement of Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 7:

See also

References

- ^ Ellis, Andy (October 2006). "EZ Street: Sus-Chord Mojo". Guitar Player.

- ^ Benward & Saker (2003), p. 77.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ a b c d e Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-300-09239-4.

- ^ a b c d e Humphries, Carl (2002). The Piano Handbook. p. 129. ISBN 0-87930-727-7.

- ^ Buckingham, Bruce; Paschal, Eric (1997). Rhythm Guitar: The Complete Guide. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-7935-8184-9. "(A9sus4 = G/A)."

- ^ Levine 1989, p. 23: "Dm7/G describes the function of the sus chord, because a sus chord is like a ii–V progression contained in one chord. The ii–V progression in the key of C is Dm7, G7."

- ^ Levine 1989, p. 24: "A persistent myth about sus chords is that 'the fourth takes the place of the third.'"

- ^ Sher, Chuck. (1991, p. 35). The New Real Book, Volume 2. Petaluma, Sher Music.

- ^ Berliner, P. (1994, pp. 678–688), Thinking in Jazz. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b Kernfeld, B. (1995, p. 68) What to Listen For in Jazz. Yale University Press

- ^ Scruton, R. (2009, p. 17) Understanding Music. London and New York, Continuum.

- ^ MacDonald 1994, p. 341.

- ^ MacDonald 1994, p. 147.

- ^ Joni Mitchell interview, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2011[full citation needed]

- ^ Bacharach, B. and David, H. (1967, p. 9) "The Look of Love" in Burt Bacharach Anthology(1989). Miami, Warner Brothers.

- ^ King. C. (1971, p. 4) "I feel the earth move" in Tapestry. Milwaukee, Hal Leonard

Sources

- Levine, Mark (1989). The Jazz Piano Book. Sher Music. ISBN 0-9614701-5-1.

- MacDonald, Ian (1994). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties. London: Fourth Estate.