Ernesto Zedillo

Ernesto Zedillo | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1999 | |

| 61st President of Mexico | |

| In office 1 December 1994 – 30 November 2000 | |

| Preceded by | Carlos Salinas de Gortari |

| Succeeded by | Vicente Fox |

| Secretary of Public Education | |

| In office 7 January 1992 – 29 November 1993 | |

| President | Carlos Salinas de Gortari |

| Preceded by | Manuel Bartlett |

| Succeeded by | Fernando Solana |

| Secretary of Programming and Budget | |

| In office 1 December 1988 – 7 January 1992 | |

| President | Carlos Salinas de Gortari |

| Preceded by | Pedro Aspe |

| Succeeded by | Rogelio Gasca |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de León 27 December 1951 Mexico City, Mexico |

| Political party | Institutional Revolutionary Party |

| Spouse |

Nilda Patricia Velasco

(m. 1974) |

| Children | 5 |

| Parent(s) | Rodolfo Zedillo Castillo Martha Alicia Ponce de León |

| Residence(s) | New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Education | National Polytechnic Institute (BA) Yale University (MA, PhD) |

| Signature |  |

Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de León CYC GColIH GCMG (Spanish pronunciation: [eɾˈnesto seˈðiʝo]; born 27 December 1951) is a Mexican economist and politician. He was President of Mexico from 1 December 1994 to 30 November 2000, as the last of the uninterrupted 71-year line of Mexican presidents from the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

During his presidency, he faced one of the worst economic crises in Mexico's history, which started only weeks after he took office.[1][2] He distanced himself from his predecessor Carlos Salinas de Gortari, blaming his administration for the crisis (although President Zedillo himself did not deviate from the neoliberal policies of his two predecessors),[1][3] and oversaw the arrest of his brother Raúl Salinas de Gortari.[4] His administration was also marked, among other things, by renewed clashes with the EZLN and the Popular Revolutionary Army;[5] the controversial implementation of Fobaproa to rescue the national banking system;[6] a political reform which allowed residents of the Federal District (Mexico City) to elect their own mayor; and the Aguas Blancas and Acteal massacres perpetrated by State forces.[7][8]

Although Zedillo's policies eventually led to a relative economic recovery, popular discontent with seven decades of PRI rule led to the party losing, for the first time, its legislative majority in the 1997 midterm elections,[9] and in the 2000 general election the right-wing opposition National Action Party's candidate Vicente Fox won the Presidency of the Republic, putting an end to 71 years of uninterrupted PRI rule.[10] Zedillo's admission of the PRI's defeat and his peaceful handing of power to his successor improved his image in the final months of his administration, and he left office with an approval rating of 60%.[11]

Since the ending of his term as president in 2000, Zedillo has been a leading voice on globalization, especially its impact on relations between developed and developing nations.

He is currently Director of the Center for the Study of Globalization at Yale University and is on the board of directors at the Inter-American Dialogue and Citigroup.

Early life and education

Ernesto Zedillo was born on 27 December 1951 in Mexico City. His parents were Rodolfo Zedillo Castillo, a mechanic, and Martha Alicia Ponce de León. Seeking better job and education opportunities for their children, his parents moved to Mexicali, Baja California.[citation needed]

In 1965, at the age of 14, he returned to Mexico City. In 1969 he entered the National Polytechnic Institute, financing his studies by working in the National Army and Navy Bank (later known as Banjército). He graduated as an economist in 1972 and began lecturing. It was among his first group of students that he met his wife, Nilda Patricia Velasco, with whom he has five children: Ernesto, Emiliano, Carlos (formerly married to conductor Alondra de la Parra[12]), Nilda Patricia and Rodrigo.

In 1974, he pursued his master's and PhD studies at Yale University. His doctoral thesis was titled Mexico's Public External Debt: Recent History and Future Growth Related to Oil.[citation needed]

Political career

Zedillo began working in the Bank of Mexico (Mexico's central bank) as a member of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, where he supported the adoption of macroeconomic policies for the country's improvement. By 1987, he was named deputy-secretary of Planning and Budget Control in the Secretariat of Budget and Planning. In 1988, at the age of 36, he headed that secretariat. During his term as Secretary, Zedillo launched a Science and Technology reform.[citation needed]

In 1992, he was appointed Secretary of Education by president Carlos Salinas. During his tenure in this post, he was in charge of the revision the Mexican public school textbooks. The changes, which took a softer line on foreign investment and the Porfiriato, among other topics, were highly controversial and the textbooks were withdrawn.[13] A year later he resigned to run the electoral campaign of Luis Donaldo Colosio, the PRI's presidential candidate.[citation needed]

1994 presidential campaign

In 1994, after Colosio's assassination, Zedillo became one of the few PRI members eligible under Mexican law to take his place, since he had not occupied public office for some time.

The opposition blamed Colosio's murder on Salinas. Although the PRI's presidential candidates were always chosen by the current president, and thus Colosio had originally been Salinas' candidate, their political relationship had been affected by a famous speech during the campaign in which Colosio said that Mexico had many problems. It is also notable that the assassination took place after Colosio visited the members of the Zapatista movement in Chiapas and promised to open dialogue, something the PRI opposed.[citation needed]

After Colosio's murder, this speech was seen as the main cause of his break with the president.[citation needed] The choice of Zedillo was interpreted as Salinas' way of bypassing the strong Mexican political tradition of non-reelection and retaining real power, since Zedillo was not really a politician, but an economist (like Salinas), who clearly lacked the president's political talent and influence. It is unclear if Salinas had attempted to control Colosio, who was generally considered at that time to be a far better candidate.

Zedillo ran against Diego Fernández de Cevallos of the National Action Party and second-timer Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas of the Party of the Democratic Revolution. He won with 48.69% of popular vote, and became the last president to distinguish the 70-year PRI dynasty in México during the 20th century.

Presidency (1994–2000)

At age 43, Zedillo assumed the presidency on 1 December 1994 at the Legislative Palace of San Lázaro, taking oath before the Congress of the Union presided by the deputy president Carlota Vargas Garza. Zedillo's electoral victory was perceived as clean, but he came to office as an accidental candidate with no political base of his own and no experience. During the first part of his presidency, he took inconsistent policy positions and there were rumors that he would resign or that there would be a coup d'état against him, which caused turmoil in financial markets.[14]

Cabinet

Zedillo's cabinet needed to have members who could deal with crises. Over the course of his presidency, he had four as Minister of the Interior, Esteban Moctezuma, who dealt with the Zapatistas; Emilio Chuayffet, who resigned following the Acteal massacre; Francisco Labastida, who won the primary to determine the 2000 PRI presidential candidate; and Diódoro Carrasco Altamirano, who dealt with the strike at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Financial Crisis of December 1994

A few days after taking office, one of the biggest economic crises in Mexican history hit the country. Although it was outgoing President Salinas who was mainly blamed for the crisis, Salinas claimed that President Zedillo made a mistake by changing the economic policies held by his administration. Zedillo devalued the peso by 15%, which prompted the near-collapse of the financial system.[15] The crisis ended after a series of reforms and actions led by Zedillo. US president Bill Clinton granted a US$20 billion loan to Mexico, which helped in one of Zedillo's initiatives to rescue the banking system.[16]

Break with Salinas

Zedillo had been an accidental presidential candidate who was vaulted to prominence with the assassination of Colosio. The conflict between Zedillo and Salinas marked the early part of Zedillo's presidency.[17] As with De la Madrid and Salinas, Zedillo had never been elected to office and had no experience in politics. His performance as a candidate was lackluster, but the outbreak of violence in Chiapas and the shock of the Colosio assassination swayed voters to support the PRI candidate in the 1994 election. In office, Zedillo was perceived as a puppet-president with Salinas following the model of Plutarco Elías Calles in the wake of the 1928 assassination of president-elect Alvaro Obregón. In order to consolidate his own power in the presidency, Zedillo had to assert his independence from Salinas. On 28 February 1995 Zedillo ordered the arrest of the ex-president's older brother Raúl Salinas for the September 1994 murder of PRI General Secretary José Francisco Ruiz Massieu. This action marked a decisive break between Zedillo and Salinas.[14]

Zapatista Crisis

Mexico had been in turmoil since January 1994, with the initial Zapatista rebellion and two political assassinations. The presidential candidate Colosio of the PRI was assassinated in March 1994, and his campaign manager Ernesto Zedillo then became the candidate a few days later. The other high-profile assassination, that of PRI Secretary General José Francisco Ruiz Massieu, brother-in-law of President Carlos Salinas de Gortari in September 1994, laid bare political rivalries within the PRI. In order to give credibility to the investigations of those political crimes and grant "a healthy distance", president Zedillo appointed Antonio Lozano Gracia a member of the opposition Political Party PAN as Attorney General of Mexico. Zedillo inherited the rebellion in Chiapas, but it was up to his administration to handle it.

On 5 January 1995, the Secretary of Interior Esteban Moctezuma started a secret meeting process with Marcos called "Steps Toward Peace" Chiapas. Talks seemed promising for an agreement, but Zedillo backed away, apparently because the military was not in accord with the government's apparent "acceptance of the Zapatistas' control over much of Chiapas territory."[18][19][20] In February 1995, the Mexican government identified the masked Subcomandante Marcos as Rafael Sebastián Guillén, a former professor at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana in Mexico City. Metaphorically unmasking Marcos and identifying him as a non-indigenous urban intellectual turned-terrorist of was the government's attempt to demystify and delegitimize the Zapatistas in public opinion. The army was prepared to move against Zapatista strongholds and capture Marcos.[21] The government decided to reopen negotiations with the Zapatistas. On 10 March 1995 President Zedillo and Secretary of the Interior Moctezuma signed the Presidential Decree for the Dialog, the Reconciliation and a peace with dignity in Chiapas law, which was discussed and approved by the Mexican Congress.[22] In April 1995, the government and the Zapatistas began secret talks to find an end to the conflict.[23] In February 1996, the San Andrés Accords were signed by the government and the Zapatistas.[24] In May 1996, Zapatistas imprisoned for terrorism were released.[25] In December 1997, indigenous peasants were murdered in an incident known as the Acteal massacre.[26] Survivors of the massacre sued Zedillo in U.S., but the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed the suit on the basis of his immunity as a head of state.[27]

Church-state relations

Salinas had gained support of the Roman Catholic Church in the 1988 elections and had pushed through a series of constitutional changes that significantly changed church-state relations. However, on 11 February 1995, Zedillo ignited a crisis with the Roman Catholic Church, hurting, recently restored Mexico–Holy See diplomatic relations.[28] Relations had already been damaged because of the 24 May 1993 political assassination of the Guadalajara Cardinal Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo and lack of government progress on solving the murder by the Attorney General of Mexico. PGR pressured the bishop of Chiapas, Samuel Ruiz García for supposedly concealing the Zapatistas guerrilla activity.[29] Ruiz's involvement had been strategic and an important instrument to keep the peace after the EZLN uprising.[30][31][32]

Poverty alleviation

Zedillo's presidential motto was Bienestar para tu familia ("Well-being for your family"). He created the poverty alleviation program Progresa, which subsidized the poorest families in Mexico, provided that their children went to school. It replaced the Salinas administration's PRONASOL, deemed too politicized.[33] It was later renamed Oportunidades (Opportunities) by president Vicente Fox. The parastatal organization CONASUPO, which was designed to supply food and provide food security to the poor was phased out in 1999, resulting in higher food prices.[34]

NAFTA and other economic measures

Carlos Salinas had negotiated Mexico's place in NAFTA, which took effect in January 1994, so Zedillo was the first president to oversee it for his entire term. The Mexican economy suffered following the December 1994 peso crisis, when currency was devalued by 15% and the U.S. intervened to prop up the economy with a multi-billion dollar loan, so that NAFTA under the Zedillo administration got off to a rocky start. The Mexican GDP was -7% and there were hopes that NAFTA would lift that miserable performance statistic.[35]

In the run-up to implementation of NAFTA, Salinas had privatized hundreds of companies. During the Zedillo administration, he privatized the state railway company, Ferrocarriles Nacionales de México. This led to the suspension of passenger service in 1997.

Electoral reform

Zedillo saw electoral reform as a key issue for his administration.[36] In January 1995, Zedillo initiated multiparty talks about electoral reform, which resulted in an agreement on how to frame political reform. In July 1996, those talks resulted in the agreement of Mexico's four major parties on a reform package, which was ratified unanimously in legislature. It created autonomous organizations to oversee elections, made the post of Head of Government of Mexico City, previously an appointed position, into an elective one, as of July 1997, and created closer oversight of campaign spending. "Perhaps most crucially, it represents a first step toward consensus among the parties on a set of mutually accepted democratic rules of the game."[37] The reforms lowered the influence of the PRI and opened opportunities for other parties.[38] In the 1997 elections, for the first time the PRI did not win the majority in Congress. Zedillo was also a strong advocate of federalism as a counterbalance to a centralized system.[39]

Foreign relations

Zedillo sought to forge new ties overseas, including ones with China.[40] He made a rhetorical gesture to Africa, but without real effect.[41]

He successfully concluded negotiations with the European Union for a Free Trade Agreement, which entered into force in July 2000 [42]

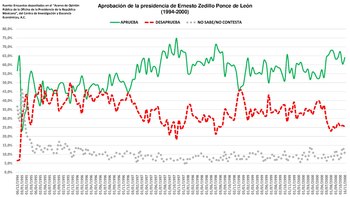

Approval ratings

In terms of its approval ratings, the Zedillo administration was a very unusual one in Mexican politics in that, while normally Presidents are highly popular upon taking office and don't experience serious downturns in their approval rate during their first year in office, Zedillo dealt with very low approval ratings only weeks after taking office due to his decision to devaluate the Peso on 20 December 1994, giving way to the Mexican peso crisis that severely hit the national economy.[43]

Hitting a bottom low 24% approval on 3 January 1995, Zedillo continued to experience low approval ratings throughout 1995, with the effects of the economic crisis, the continuing conflict with the EZNL in Chiapas and the Aguas Blancas massacre in June preventing his popularity from recovering. Although not as troublesome as 1995, his approval ratings remained unsteady during 1996.

Zedillo's approval ratings, however, experienced a steady growth beginning in January 1997, and for the rest of his administration his disapproval rate was never higher than his approval rate. Helped in no doubt by the relative economic recovery and the peaceful transfer of power to Vicente Fox (who won the 2000 presidential elections, being the first opposition candidate in 71 years to defeat the ruling PRI), Zedillo left office with an approval rate of 64% and a disapproval rate of 25.4%.[44]

On average, Zedillo's administration had an approval rating of 55.3% and a disapproval rating of 34.3%.

An interesting occurrence is that of the aforementioned 3 January 1995 poll: at the same time that Zedillo recorded his lowest-ever approval rate and a disapproval rate of 30%, 46.1% of those polled either stated that they didn't have an opinion on his administration or didn't answer, making it the only case ever recorded in Mexican modern history in which a plurality expressed no opinion on a sitting President.[45]

Highest approval ratings:

- 15 October 1997 (74.8% approval).

- 1 September 1997 (71.4% approval).

- 1 July 1998 (71.3% approval).

Lowest approval ratings:

- 3 January 1995 (24% approval).

- 16 January 1995 (31.4% approval).

- 1 February 1995 (35.7% approval).

Highest disapproval ratings:

- 17 November 1995 (49.8% disapproval).

- 2 May 1995 (48.8% disapproval).

- 1 March 1995 (45.9% disapproval).

Lowest disapproval ratings:

- 6 December 1994 (6.5% disapproval).

- 15 December 1994 (7.2% disapproval).

- 15 October 1997 (18.2% disapproval).

2000 Election

The presidential election of 2 July 2000 was a watershed in Mexican history for several reasons. The PRI presidential candidate, Francisco Labastida was not designated by the sitting president (as all former presidential nominees from the PRI had been until that point), but by an open internal primary of the party.[46] Changes in the electoral rules meant that the government did not control voting as it had previously in the Ministry of the Interior. Elections were now the jurisdiction of the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE), with Mexicans having faith that elections would be free and fair.[47] IFE implemented new procedures regarding campaigns and balloting, with rules for finance, guarantee of the secret ballot, and unbiased counting of votes. Also important were some 10,000 Mexican poll watchers and over 850 foreign observers, including ex-president of the U.S., Jimmy Carter. Zapatista leader Subcomandante Marcos declared that the election was a "dignified and respectable battleground."[48] The results of the election were even more historic. For the first time since the founding of Zedillo's party in 1929, an opposition candidate won, a peaceful change from an authoritarian government.[49] Zedillo went on national television when the polls closed, declaring that Vicente Fox had won. In Fox's autobiography he writes, "There are still those old-guard priistas who consider Ernesto Zedillo a traitor to his class for his actions on the night of 2 July 2000, as the party boss who betrayed the machine. But in that moment President Zedillo became a true democrat ... In minutes he preempted any possibility of violent resistance from hard-line priistas. It was an act of electoral integrity that will forever mark the mild-mannered economist as a historic figure of Mexico's peaceful transition to democracy."[50]

Post-presidency

Since leaving office, Zedillo has held many jobs as an economic consultant in many international companies and organizations. He currently is on the faculty at Yale University, where he teaches economics and heads the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization. In 2008, a conference on global climate change was convened at Yale, resulting in a published volume edited by Zedillo.[51]

Corporate boards

- Alcoa, Member of the Board of Directors

- Citigroup, Member of the Board of Directors (since 2010)[52]

- Coca-Cola, Member of the International Advisory Board

- Electronic Data Systems, Member of the Board of Directors

- Stonebridge International, Member of the Board of Advisors[53]

- Procter & Gamble, Member of the Board of Directors (2001-2019)[54]

- Union Pacific Corporation, Member of the Board of Directors (2001-2006)

Non-profit organizations

- Kofi Annan Foundation, Member of the Commission on Elections and Democracy in the Digital Age (since 2018)[55]

- Berggruen Institute, Member of the Board of Directors[56]

- Migration Policy Institute (MPI), Co-Chair of the Regional Migration Study Group[57]

- Aurora Prize, Member of the Selection Committee (since 2015)[58]

- The Elders, Member (since 2013)[59]

- Natural Resource Charter, Chair of the Oversight Board (since 2011)

- American Philosophical Society, Member (since 2011)[60]

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Member of the Global Development Program Advisory Panel (since 2007)[61]

- Group of Thirty, Member (since 2005)

- Inter-American Dialogue, Member (since 2003)[62]

- Center for Global Development (CGD), Member of the Advisory Group[63]

- Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), Honorary Member of the Board of Directors[64]

- Millstein Center for Corporate Governance and Performance at the Yale School of Management, Member of the Advisory Board

- Club of Madrid, Member

- Americas Quarterly, Member of the Editorial Board

In 2009, Zedillo headed an external review of the World Bank Group's governance.[65] Since 2019, he has been serving on the High-Level Council on Leadership & Management for Development of the Aspen Management Partnership for Health (AMP Health).[66] In 2020, he joined the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (IPPR), an independent group examining how the WHO and countries handled the COVID-19 pandemic, co-chaired by Helen Clark and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.[67]

In 2016, Zedillo co-signed a letter calling for an end to the War on Drugs, along with people like Mary J. Blige, Jesse Jackson and George Soros.[68]

Lawsuit in the U.S. by Indigenous Mexican Plaintiffs

According to a 2012 Economist article, a group of ten anonymous Tzotzil people claiming to be survivors of the Acteal massacre have taken an opportunity to sue former President Zedillo in a civil court in Connecticut, "seeking about $50 million and a declaration of guilt against Mr Zedillo." The victims of the massacre were members of an indigenous-rights group known as Las Abejas; however, the current president of that organization, Porfirio Arias, claims that the alleged victims were in fact not residents of Acteal at all. This has led commentators to allege the trial to be politically motivated, perhaps by a member of his own political party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party, angry about Zedillo's reforms that led to the party losing power in the 2000 Mexican presidential election, after 71 years of continuous political rule.[69]

The United States Department of State recommended that President Zedillo be granted immunity from prosecution due to the actions occurring as part of his official capacity as head of state. This motion is not binding in the US court system, but judges "generally side with the State Department."[70]

The plaintiffs, who are being represented by Rafferty, Kobert, Tenenholtz, Bounds & Hess may appeal the ruling of U.S. District Judge Michael Shea to sidestep the immunity Zedillo has been granted.[71]

In 2014, the US Supreme Court refused to hear a case against Zedillo on grounds of "sovereign immunity" as a former head of state by survivors of the Acteal massacre.[27]

Public opinion and legacy

In a national survey conducted in 2012 by BGC-Excélsior regarding former Presidents, 39% of the respondents considered that the Zedillo administration was "very good" or "good", 27% responded that it was an "average" administration, and 31% responded that it was a "very bad" or "bad" administration.[72]

Honors

Argentina:

Argentina:

Grand Collar of the Order of the Liberator General San Martín (1996)[73]

Grand Collar of the Order of the Liberator General San Martín (1996)[73]

Estonia:

Estonia:

Collar of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana (27 October 1995)

Collar of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana (27 October 1995)

Spain:

Spain:

Collar of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (19 January 1996)[74]

Collar of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (19 January 1996)[74]

Uruguay

Uruguay

Portugal:

Portugal:

Grand Collar of the Order of Prince Henry (30 September 1998)

Grand Collar of the Order of Prince Henry (30 September 1998)

United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (1998)

Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (1998)

See also

References

- ^ a b "The peso crisis, ten years on: Tequila slammer". The Economist. 29 December 2004. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ "The Tequila crisis in 1994". Rabobank. 19 September 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ "Salinas vs. Zedillo" (in Spanish). La Jornada. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Salinas' Brother Charged in Mexican Assassination New York Times 1 March 1995 [1]

- ^ . 17 October 2013 https://web.archive.org/web/20131017111100/http://www.letraslibres.com/sites/default/files/pdfs_articulos/pdf_art_5673_5540.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Solís, L. (comp.) (1999). Fobaproa y las recientes reformas financieras. México: Instituto de Investigación Económica y Social "Lucas Alamán", A.C.

- ^ "Resuelve SCJN Atraer Caso de Acteal". Archive.is. 3 September 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "La matanza de Aguas Blancas". Archived from the original on 30 November 2006. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Nohlen, D (2005) Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I, p453 ISBN 978-0-19-928357-6

- ^ Nohlen, D (2005) Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I, p475 ISBN 978-0-19-928357-6

- ^ Aznarez, Juan Jesus (1 December 2000). "Zedillo abandona la presidencia con una popularidad del 60%". El Pais. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Gilbert, Dennis (1997). "Rewriting History: Salinas, Zedillo and the 1992 Textbook Controversy". Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos. 13 (2): 271–297. doi:10.2307/1052017. JSTOR 1052017.

- ^ a b Thomas Legler, "Ernesto Zedillo" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p.1641

- ^ Legler, "Ernesto Zedillo", p. 1641.

- ^ "Clinton authorizes loan to Mexico". History (U.S. TV channel). 31 January 1995. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Fuentes, Carlos (1995). "Coalticue's Skirt: Hidden Aspects of Mexico's Political Rivalry in 1995". The Brown Journal of World Affairs. 2 (2): 175–180. JSTOR 24590093.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Bordering on Chaos, p. 242.

- ^ "Zedillo rompió acuerdo de paz con el EZLN: Esteban Moctezuma - Proceso". Proceso.com.mx. 11 January 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ "El Universal - Opinion - Renuncia en Gobernación". Eluniversalmas.com.mx. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Bordering on Chaos, pp. 244-45

- ^ "Client Validation". Zedillo.presidencia.gob.mx. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ "Cronologia del Conflicto EZLN". Latinamericanstudies.org. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20070206140008/http://www.globalexchange.org/countries/americas/mexico/SanAndres.html accessed 23 March 2019

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Death in Chiapas". The New York Times. 25 December 1997.

- ^ a b "Supreme Court won't hear suit over Indian massacre in Mexico". Indianz. 8 October 2014.

- ^ "A 15 años de relaciones entre México y el Vaticano". Jornada.unam.mx.

- ^ "MEXICO: Satanizado y admirado, obispo en el centro de la polemica". Ipsnoticias.net. 17 February 1995.

- ^ "La Sedena sabía de la existencia de la guerrilla chiapaneca desde 1985 (Segunda y última parte)". Proceso.com. 20 March 2006.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Rocha Menocal, Alina (August 2001). "Do Old Habits Die Hard? A Statistical Exploration of the Politicisation of Progresa, Mexico's Latest Federal Poverty-Alleviation Programme, under the Zedillo Administration". Journal of Latin American Studies. 33 (3): 513–538. doi:10.1017/S0022216X01006113. S2CID 144747458.

- ^ Yunez–Naude, Antonio (January 2003). "The Dismantling of CONASUPO, a Mexican State Trader in Agriculture". The World Economy. 26 (1): 97–122. doi:10.1111/1467-9701.00512. S2CID 153903071.

- ^ de la Mora, Luz María (1997). "North American Free Trade Agreement". In Werner, Michael S. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Mexico: M-Z. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 1026. ISBN 978-1-884964-31-2.

- ^ Zedillo, Ernhsto (1996). "The Right Track: Political and Economic Reform in Mexico". Harvard International Review. 19 (1): 38–67. JSTOR 42762264.

- ^ Thomas Legler, "Ernesto Zedillo" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 1641-42.

- ^ Bruhn, Kathleen (1999). "The resurrection of the Mexican left in the 1997 elections: implications for the party system". In Domínguez, Jorge I.; Poire, Alejandro; Poiré, Alejandro (eds.). Toward Mexico's Democratization: Parties, Campaigns, Elections, and Public Opinion. Psychology Press. pp. 88–113. ISBN 978-0-415-92159-6.

- ^ León, Ernesto Zedillo Ponce De (1999). "Address by Ernesto Zedillo Ponce De León". Publius. 29 (4): 15–22. doi:10.2307/3330905. JSTOR 3330905.

- ^ Cornejo, Romer Alejandro (2001). "México y China. Entre la buena voluntad y la competencia". Foro Internacional. 41 (4 (166)): 878–890. JSTOR 27739097.

- ^ Varela, Hilda (2001). "Crónica de una política inexistente: las relaciones entre México y África, 1994-2000". Foro Internacional. 41 (4 (166)): 912–930. JSTOR 27739100.

- ^ https://eulacfoundation.org/es/system/files/Mexico%20y%20la%20Unión%20Europea%20en%20el%20sexenio%20de%20Zedillo.pdf [dead link]

- ^ "The Tequila crisis in 1994". Rabobank. 19 September 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Gira del presidente Zedillo a Singapur y Brunei". Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, AC. 16 November 2000. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Oficina de la Presidencia de la República Mexicana (3 January 1995). "Mensaje sobre el Programa de emergencia económica" [Message about the Economic Emergency Program] (Document) (in Spanish). hdl:10089/1633.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help) - ^ Bruhn, Kathleen (2004). "The making of the Mexican president, 2000: parties, candidates, and campaign strategy". In Domínguez, Jorge I.; Lawson, Chappell H. (eds.). Mexico's Pivotal Democratic Election: Candidates, Voters, and the Presidential Campaign of 2000. Stanford University Press. pp. 123–156. ISBN 978-0-8047-4974-9.

- ^ Wallis, Darren (July 2001). "The Mexican Presidential and Congressional Elections of 2000 and Democratic Transition". Bulletin of Latin American Research. 20 (3): 304–323. doi:10.1111/1470-9856.00017.

- ^ Fröhling, Oliver; Gallaher, Carolyn; Jones, III, John Paul (January 2001). "Imagining the Mexican Election". Antipode. 33 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00155.

- ^ Klesner, Joseph L. (March 2001). "The End of Mexico's One-Party Regime". PS: Political Science & Politics. 34 (1): 107–114. doi:10.1017/S1049096501000166. S2CID 153947777.

- ^ Vicente Fox and Rob Allyn, Revolution of Hope: The Life, Faith, and Dreams of a Mexican President. New York: Viking 2007, pp. 192-93.

- ^ Ernesto Zedillo, ed., Global Warming. Looking Beyond Kyoto. Brookings Institution Press 2008

- ^ Smith, Randall (27 February 2010). "Citigroup to Restructure Its Board". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Member of the Board of Directors: Ernesto Zedillo Archived 31 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine Procter & Gamble.

- ^ Kofi Annan Commission on Elections and Democracy in the Digital Age Kofi Annan Foundation.

- ^ Board of Directors Berggruen Institute.

- ^ Regional Migration Study Group Migration Policy Institute (MPI).

- ^ Selection Committee Aurora Prize.

- ^ "Kofi Annan announces two new Elders: Hina Jilani and Ernesto Zedillo". TheElders.org. 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 24 August 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Program Advisory Panels Announced by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, press release of 2007.

- ^ "Inter-American Dialogue | Ernesto Zedillo". Thedialogue.org. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ Advisory Group Center for Global Development (CGD).

- ^ Board of Directors Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE).

- ^ "Outside Review Supports World Bank Group Reform". Web.worldbank.org. 21 October 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Members of the High-Level Council on Leadership & Management for Development Aspen Management Partnership for Health (AMP Health).

- ^ "Pandemic review panel named, includes Miliband, ex Mexican president". Reuters. 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Over 1,000 Leaders Worldwide Slam Failed Prohibitionist Drug Policies, Call for Systemic Reform". Drug Policy Alliance.

- ^ "Mexico and Justice: The trials of Ernesto Zedillo". The Economist. 1 September 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Archibold, Randal C. (8 September 2012). "U.S. Moves to Grant Former Mexican President Immunity in Suit". The New York Times.

- ^ June, Daniel (22 July 2013). "Former Mexican President Evades Charges of Massacre Through Immunity". JD Journal.

- ^ Beltran, Ulises (29 October 2012). "Zedillo y Fox los ex presidentes de México más reconocidos". Imagen Radio. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ "Decreto 707/97". argentina.gob.ar (in Spanish). Government of Argentina. 1996.

- ^ "Royal Decree 50/1996, 19th January". Spanish Official Journal - BOE (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ "Resolución N° 813/996". www.impo.com.uy. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

Further reading

- Manaut, Raúl Benítez (2001). "Seguridad nacional y transición política, 1994-2000". Foro Internacional. 41 (4 (166)): 963–991. JSTOR 27739103.

- Castañeda, Jorge G. Perpetuating Power: How Mexican Presidents Were Chosen. New York: The New Press 2000. ISBN 1-56584-616-8

- Cornelius, Wayne A., Todd A. Eisenstadt, and Jane Hindley, eds. Sub-national Politics and Democratization in Mexico. San Diego: Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California, 1999

- Rodríguez, Rogelio Hernández (2003). "Ernesto Zedillo. La presidencia contenida". Foro Internacional. 43 (1 (171)): 39–70. JSTOR 27739165.

- Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997. ISBN 0-06-016325-9

- Langston, Joy (August 2001). "Why Rules Matter: Changes in Candidate Selection in Mexico's PRI, 1988–2000". Journal of Latin American Studies. 33 (3): 485–511. doi:10.1017/S0022216X01006137. S2CID 144628342.

- Pardo, María del Carmen (2003). "Introducción el último gobierno de la hegemonía priista". Foro Internacional. 43 (1 (171)): 5–9. JSTOR 27739163.

- Preston, Julia and Samuel Dillon. Opening Mexico: The Making of a Democracy. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux 2004.

- Purcell, Susan Kaufman and Luis Rubio (eds.), Mexico under Zedillo (Boulder, CO, and London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998)

- Schmidt, Samuel (2000). México encadenado: El legado de Zedillo y los retos de Fox. Mexico D.F.: Colibrí.

- Villegas M., Francisco Gil (2001). "México y la Unión Europea en el sexenio de Zedillo". Foro Internacional. 41 (4 (166)): 819–839. JSTOR 27739094.

External links

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Ernesto Zedillo at IMDb

- Template:Worldcat id

- Ernesto Zedillo collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- (in Spanish) Extended biography by CIDOB Foundation

- (in Spanish) The website of Ernesto Zedillo during his presidency

- 1951 births

- Living people

- 20th-century Mexican politicians

- Candidates in the 1994 Mexican presidential election

- Collars of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Directors of Citigroup

- Group of Thirty

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Institutional Revolutionary Party politicians

- Instituto Politécnico Nacional alumni

- Members of the Inter-American Dialogue

- Mexican economists

- Mexican expatriates in the United States

- Mexican people of European descent

- Mexican Roman Catholics

- Mexican Secretaries of Education

- Politicians from Mexico City

- Presidents of Mexico

- Procter & Gamble people

- Recipients of the Collar of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana

- Recipients of the Four Freedoms Award

- Recipients of the Medal of the Oriental Republic of Uruguay

- Recipients of the Olympic Order

- Recipients of the Order of the Star of Romania

- Yale University alumni

- Yale University faculty