Local nonsatiation

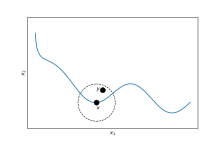

The property of local nonsatiation of consumer preferences states that for any bundle of goods there is always another bundle of goods arbitrarily close that is strictly preferred to it.[1]

Formally, if X is the consumption set, then for any and every , there exists a such that and is strictly preferred to .

Several things to note are:

- Local nonsatiation is implied by monotonicity of preferences. However, as the converse is not true, local nonsatiation is a weaker condition.

- There is no requirement that the preferred bundle y contain more of any good – hence, some goods can be "bads" and preferences can be non-monotone.

- It rules out the extreme case where all goods are "bads", since the point x = 0 would then be a bliss point.

- Local nonsatiation can only occur either if the consumption set is unbounded or open (in other words, it is not compact) or if x is on a section of a bounded consumption set sufficiently far away from the ends. Near the ends of a bounded set, there would necessarily be a bliss point where local nonsatiation does not hold.

Applications of Local nonsatiation

Local nonsatiation is often applied in consumer theory, a branch of microeconomics, as an important property often assumed in theorems and propositions. Consumer theory is a study of how individuals make decisions and spend their money based on their preferences and budget. Local nonsatiation is also a key assumption for the First welfare theorem.[2][3]

An indifference curve is a set of all commodity bundles providing consumers with the same level of utility. The indifference curve is named so because the consumer would be indifferent between choosing any of these bundles. The indifference curve has a negative slope. This is caused because of nonsatiation. The indifference curve can not slope upward because the consumer can not be indifferent between two commodity bundles if contains more of both goods.

Local nonsatiation is a key assumption in the Walras’ law theorem. Walras's law says that if consumers have locally nonsatiated preferences, they will consume their entire budget over their lifetime.[1][2]

The indirect utility function is a function of commodity prices and the consumer's income or budget. Indirect utility function v(p, w) where p is a vector of commodity prices, and w is an amount of income. Important assumption is that consumers have locally nonsatiated preferences. Related to the indirect utility function are utility maximization problem (UMP) and expenditure minimization problem (EMP). The UMP considers a consumer who wants to gain the maximum utility given wealth w. The EMP considers a consumer who wants to find a cheapest way to reach a certain level of utility. In both EMP and UMP consumers are assumed to have locally nonsatiated preferences.

The Slutsky equation describes the relationship between the Hicksian and Marshallian demands. Also shows the response of Marshallian demand to price changes. Preferences are supposed to be locally nonsatiated.[1]

Market is at competitive equilibrium if there are no monopolies in the market. This means that prices are such that demand is equivalent to the supply for each good. Consumers trying to maximize their utility and producers trying to maximize their profit are satisfied with what they are getting. Competitive equilibrium may fail to exist if consumers are satiated, thus are assumed to be nonsatiated.[4]

The first fundamental theorem of welfare economics states that any competitive equilibrium in a market, where consumers are locally nonsatiated is pareto optimal (pareto optimal is when no changes in economy can make one party better off without making another party worse off).[5]

Notes

- ^ a b c Microeconomic Theory, by A. Mas-Colell, et al. ISBN 0-19-507340-1

- ^ a b https://web.stanford.edu/~jdlevin/Econ%20202/Consumer%20Theory.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Kaliszyk, Cezary; Parsert, Julian (2018). "Formal microeconomic foundations and the first welfare theorem". Proceedings of the 7th ACM SIGPLAN International Conference on Certified Programs and Proofs. pp. 91–101. doi:10.1145/3167100. ISBN 9781450355865. S2CID 19561356.

- ^ Sato, Norihisa (2010). "Satiation and existence of competitive equilibrium". Journal of Mathematical Economics. 46 (4): 534–551. doi:10.1016/j.jmateco.2010.03.006.

- ^ https://math.mit.edu/~apost/courses/18.204_2018/Sicong_Shen_paper.pdf [bare URL PDF]