Linacre College, Oxford

| Linacre College | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford | ||||||||

| ||||||||

Arms: see below | ||||||||

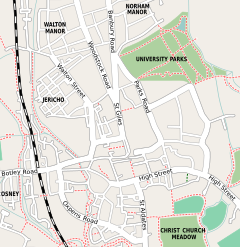

| Location | St Cross Road | |||||||

| Coordinates | 51°45′34″N 1°14′59″W / 51.75935°N 1.24984°W | |||||||

| Motto | No End To Learning | |||||||

| Established | 1962 | |||||||

| Named for | Thomas Linacre | |||||||

| Previous names | Linacre House (until 1965) | |||||||

| Sister college | Hughes Hall, Cambridge | |||||||

| Principal | Nick Brown | |||||||

| Undergraduates | None | |||||||

| Postgraduates | 550 | |||||||

| Grace | Benedictus benedicat | |||||||

| Endowment | £19.0 million (2020)[1] | |||||||

| Website | www | |||||||

| Boat club | Linacre College Boat Club | |||||||

| Map | ||||||||

Linacre College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in the UK whose members comprise approximately 50 fellows and 550 postgraduate students.

Linacre is a diverse college in terms of both the international composition of its members (the majority of whom are from outside the UK and represent 133 countries), as well as the disciplines studied. Linacre was the first graduate college in the UK for both sexes and all subjects. Unlike most colleges, students and fellows share the same common room and there is no high table.

The college is named after Thomas Linacre (1460–1524), founder of the Royal College of Physicians as well as a distinguished renaissance humanist — multidisciplinary interests that the college aims to reflect.

The college is located on St Cross Road at its junction with South Parks Road, bordering University Parks to the north and the University Science Area to the west.

History

Linacre College (called Linacre House for its first three years) was the UK's first graduate society for both sexes and all subjects.[2] Founding Principal John Bamborough described it as "a deliberate experiment by the University to see whether the needs of graduate students could be met by a new type of society."[3]

It was founded on 1 August 1962, in premises on St Aldate's formerly occupied by St Catherine's Society (now St Catherine's College) and currently home to the university's Music Department. Initially there were 115 members of whom only 30 were British. The first senior members included Isaiah Berlin, Dorothy Hodgkin and John Hicks.[4]

In 1977, Linacre moved to its present site at Cherwell Edge, a Queen Anne building designed in part by Basil Champneys, which was formerly a private home, a convent of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus, and a residence for students of other colleges.[3] In November 1964 Linacre became a self-governing society[3] and then on 1 August 1986 Linacre became an independent college of Oxford University by Royal Charter.[5] Since 2010 the principal has been Nick Brown.

On 31 October 2021 the college signed a memorandum of understanding with SOVICO Group, represented by their chairwoman Nguyen Thi Phuong Thao to receive a donation of £155 million. The MoU sets out the intention to create a new graduate centre and endow graduate access scholarships. After receipt of the first £50 million, the College will approach the Privy Council to ask for permission to change the name from Linacre College to Thao College.[6][7][8] The donation and proposed name change has been a source of controversy for some university staff and students due to SOVICO's interests in fossil fuel industries.[7]

Coat of arms and motto

In 1988 Linacre College was granted a coat of arms blazoned:

- Sable an open Book proper edged Or bound Gules the dexter page charged with the Greek Letter Alpha the sinister page charged with the Greek Letter Omega both Sable the whole between three Escallops Argent.[citation needed]

The college motto beneath the escutcheon is No End To Learning. College colours are grey, yellow and black (or silver, gold and sable) but only the latter two colours are used for rowing blades and most sports clothing.[citation needed]

Both scallop shells and the alpha and omega are common symbols in heraldry and can have religious significance. Scallop shells are traditionally a symbol of the Way of St. James (pilgrimage route to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela) and alpha and omega often a Christian reference to God. A secular interpretation is as reference to the completeness of study (alpha being the first letter of the Greek alphabet and omega the last) and the process of scholarship akin to a pilgrimage/journey.[citation needed]

College grace

The college grace is said in Latin by the Principal (or a designated fellow) at formal dinners in Hall. Before commencement of the meal the words "Benedictus benedicat" ('May the Blessed One give a blessing') are said, all standing. After the completion of the meal the words "Benedicto benedicatur" ('May the Blessed One be blessed') are said, all standing.[citation needed]

Buildings and facilities

Linacre's main site is on the corner of South Parks Road and St Cross Road. In addition to the original building of 1886 (now known as the OC Tanner Building) there are three much newer accommodation blocks on the main site, all built of "Linacre College Special Blend Brick" with matching Queen Anne style architecture.[9] The Bamborough, Abraham, and Griffiths buildings were completed in 1986, 1995, and 2008 respectively,[10] raising the total number of student rooms on the main college site to 92.[11]

OC Tanner Building

The oldest part of the college, known as the OC Tanner Building, contains most of the central facilities, all staff offices and some student accommodation. The heart of the building is the large common room, which has a bar and other leisure facilities. The college library, formerly a chapel,[12] includes shared computing facilities for college members.

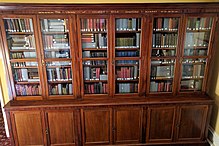

Gilbert Ryle Collection

As well as the main library there is also Gilbert Ryle's personal library, part of which he donated in 1968, and the remainder after his death in 1976. Ryle was involved in the creation of Linacre House in 1962, when the institution had no library. When Ryle retired in 1968, he donated many of his books to Linacre College, and the remainder of the collection after he died in 1976. The books are stored in the Linacre Bookcase and are available for use in the Linacre Library.[13]

Bamborough Building

The first major addition to the main college site was the Bamborough Building, which opened in 1985 and was officially named in 1986. It is located beside the OC Tanner Building to form a quad featuring an ornamental fountain. A plaque on the Bamborough Building commemorates it winning an Oxford Preservation Trust award in 1987.[citation needed]

Abraham Building

The Edward & Asbjörg Abraham Building, completed in 1995, is primarily a residential building offering single bedrooms for students. It was designed and built as part of a movement within Linacre to raise environmental awareness and promote sustainable development. The building was named UK Green Building of the Year 1996[14] and won the BCE Environmental Leadership Award as well as the Oxfordshire special conservation award of 1995.[15] A photovoltaic system was installed on the roofs of Abraham and Griffiths Buildings in 2011. The quad enclosed by the Tanner, Abraham and Griffiths buildings was named in 2012 after Jaki Leverson a former student,[16][17] and contains a sculpture entitled 'The Dancing Phoenix' by Hugo Powell.[18][19]

The basement of the Abraham Building houses a music practice room and the college gym, which has four ergometers, a good range of weights, various other gym equipment and space for several classes.[citation needed]

Griffiths Building

The newest residence on the main site is the Griffiths Building, named after former student and Honorary Fellow Rodney Griffiths. Completed in 2008, the building has 28 en suite single rooms and 4 en suite double rooms with shared kitchens. It was a finalist for two awards of The Brick Development Association.[20][21]

Dining Hall

Between the OC Tanner and Abraham Buildings is Linacre's large dining hall, added in 1977, which operates a canteen service most weekdays for lunch and evening meal.[citation needed]

The Rom Harré Garden

The most recent major development at Linacre has been the completion of a garden extension on the main site of the college in 2010. This is a quiet spot with flowers and outdoor seating. Rom Harré is a former Vice-Principal and Emeritus Fellow.[citation needed]

Off site accommodation

Linacre also owns or leases a number of buildings off the main site, including properties on Banbury Road, Bradmore Road, Divinity Road, Iffley Road, Stanley Road and Walton Street, which provide a further 102 rooms (including rooms for couples).[22] The college generally offers accommodation to all first-year students (freshers) and the percentage of graduate students housed within college accommodation exceeds the university average. Students typically move into private shared housing in and around Oxford after their first year.[citation needed]

Photograph gallery

-

Main Entrance

-

View from the west

-

OC Tanner Building

-

Library in Old Chapel

-

Abraham Building

-

Griffiths Building

-

Dining Hall

-

Rom Harré Garden

-

The college's arms on oak wood

Student life

Common Room

Much of the college's social and sporting life is coordinated through the Common Room, of which all students, fellows and staff are members. The Common Room's elected executive committee oversees activities and works closely with college officials to represent its members' interests.[citation needed]

The Common Room organises numerous events during term time. Particular highlights include termly bops, which are among the largest student-run parties in Oxford. Operating across two floors and outside areas, the bops are themed parties open to members of other colleges. The biggest bop of the year is usually the matriculation bop ("sexy sub-fusc” theme) which usually attracts a queue far in excess of the 450 person capacity. In 2015, 750 people enjoyed the event at any given time, and more than 950 people attended it throughout the night. Other social events include smaller college parties, movie nights, cake baking, cheese and wine tasting and lectures.[citation needed]

Clubs and societies

Like all colleges, Linacre has many active sports teams and its members also represent the university in various sports. Active societies and clubs include the Linacre Music Society, Linacre College Boat Club, Linacre Recreational Football Society, Linacre Ladies that Lift weightlifting society, Linacre Yoga Society, Linacre Green Society, and Linacre Intercultural Society and Linacre Photo Society, among others.[citation needed]

Sustainability and ethics

The college has a strong environmental ethos and has gained a reputation as the 'green' college of Oxford through a number of environmental initiatives over the years including an official sustainability policy.[23][24][25] Linacre has been ranked greenest college by OUSU in a number of years.[26][27][28] The common room executive hosts an environment officer and there is an active green society since 2007 as well as an allotment society.[29][30][31][32] Linacre's Abraham building won Green Building of the Year 1996[14] and as well as the BCE Environmental Leadership Award.[15] In 2006 Linacre became the first carbon neutral college in Oxford by offsetting carbon emissions with a three-year contract with ClimateCare but stopped being carbon neutral in 2008.[33][34]

In 2010 Linacre committed to the 10:10 campaign to reduce carbon emissions 10% that year.[35] It has more recently set a target of 40% reduction over ten years until 2020.[36] A photovoltaic system was installed on the roofs of Abraham and Griffiths Buildings in 2011. In 2016 Linacre invested £100,000 into the Low Carbon Hub, a renewable energy social enterprise.[25][37] Linacre was the first Oxford college to achieve fairtrade status in September 2006.[38][39] In 2016 Linacre also hosted a seminar series on the sustainability and ethics of banking.[40]

Linacre runs two major public lectures each year:

Linacre Lectures on the Environment

Throughout its history the college has run an annual series of Linacre Lectures open to non-members, the first of which were given by Brian Aldiss, Robert Graves and Isaiah Berlin.[41] Since 1991 these public lectures have focused on environmental challenges.[42]

- 2017: John Knox, "Global Threats to Environmental Human Rights Defenders".[43]

- 2014: Michael Oppenheimer, "Migration, Interconnection, Conflict: Emergent Issues and Indirect Impacts in IPCC’s Fifth Assessment"[44]

- 2013: Mike Gidney, David Heath, and Gordon McGranahan on "Food Security and Sustainability"[45]

- 2012: Carl Folke, Robert Costanza, and others on "Environmental Governance and Resilience"[45]

- 2011: Lester R. Brown, Paul Ekins, and others on "Riding the Perfect Storm"[46]

- 2019: Strobe Talbott, "A President for Dark Times: the Age of Reason Meets the Age of Trump".[47]

- 2018: Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, "Economics for the Human Race".[48]

- 2017: George F. R. Ellis, "On the Origin and Nature of Values".[49]

- 2016: Shirley Williams, "The Value of Europe and European Values".[50]

- 2015: Peter Singer, "From Moral Neutrality to Effective Altruism: The Changing Scope and Significance of Moral Philosophy".[51]

- 2014: Shami Chakrabarti, "Human Rights as Human Values".[52]

- 2013: Michael Ignatieff, "Representation and Responsibility: Ethics and Public Office".[53]

People associated with the college

Notable alumni

- Juan Ossio Acuña, anthropologist and historian, and the first Peruvian Minister of Culture

- Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, journalist

- Carolyn Browne, diplomat, British Ambassador to Kazakhstan, former British Ambassador to Azerbaijan

- Deborah Cadbury, author and television producer

- Edward Chen, CBE, GBS, Professor and Fellow of the Centre of Asian Studies at the University of Hong Kong

- Nigel A. L. Clarke, Minister of Finance and the Public Service of Jamaica and Jamaican Member of Parliament

- Heather Couper, astronomer, television and radio presenter, writer, and film producer; served as commissioner for the Millennium Commission

- Gianni De Fraja, Professor of Economics at the University of Nottingham

- Flavio Delbono, Italian economist and politician

- Satsuki Eda, served as President of the House of Councillors of Japan

- Neil Ferguson, OBE FMedSci, epidemiologist, Professor of Mathematical Biology and head of the Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at Imperial College London

- Raymond Flood, former Gresham Professor of Geometry at Gresham College

- Philip A. Gale, Professor of Chemistry and Head of School, University of Sydney

- Elspeth Garman, Professor of Molecular Biophysics at Oxford

- David Gavaghan, Professor of Computational Biology at Oxford

- Frene Ginwala, South African politician and former journalist

- Carolyn Tanner Irish, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Utah

- Dafydd Glyn Jones, Welsh scholar and lexicographer

- Joanna Kavenna, novelist, essayist and travel writer, Granta Best of Young British Novelists 2013

- David Kelly, biological weapons expert

- John Keown, Rose F. Kennedy Professor of Christian Ethics at Georgetown University[54]

- Guy Lloyd-Jones, FRS, FRSE, Forbes Professor of Organic Chemistry at the University of Edinburgh

- Jef McAllister, American journalist, author and lawyer, former White House Correspondent and London Bureau Chief of Time magazine

- Alister McGrath, Andreas Idreos Professor of Science and Religion at Oxford

- P. Michael McKinley, United States Ambassador to Brazil, former United States Ambassador to Afghanistan, Colombia, and Peru

- Urjit Patel, 24th Governor of the Reserve Bank of India

- Anthony Pierce, former Bishop of Swansea and Brecon

- Kenneth Joseph Riley, former Canon Precentor at Liverpool Cathedral

- Ian Stanes, former Archdeacon of Loughborough

- Brian Tanner, Professor of Physics and Dean of Knowledge Transfer at Durham University

- Paul Tellier, former Clerk of the Privy Council (Canada)

- Stephen Venner, Bishop to the Forces and Bishop for the Falkland Islands

- Keith Ward, British cleric, philosopher and theologian

- Jake Wetzel, Olympic gold medallist rower

- Martin Wharton, Bishop of Newcastle

- The Lady Gabriella Windsor, anthropologist and freelance journalist

Fellows

- Silke Ackermann, Director of the History of Science Museum, Oxford, and the first woman to direct a museum at the university

- Martin Aitken, FRS, Oxford professor of archaeometry[55]

- Hazel Assender, Associate Professor in Materials at Oxford

- James Bennett, Professor of the History of Science at Oxford, former Director of the History of Science Museum, Oxford

- Hermann Blaschko, Reader in Biochemical Pharmacology at Oxford

- Brian Catling, Professor of Fine Art at the Ruskin School of Art

- Rupert Cecil, World War II bomber pilot (DFC and Bar), scientific intelligence officer, and first Dean and Vice Principal of Linacre College[56]

- Chris Dobson, chemist and structural biologist, and Master of St John's College, Cambridge

- Ursula Dronke, former Vigfússon Reader in Old Norse at Oxford

- Terry Eagleton, literary critic and theorist, Distinguished Professor of English Literature at Lancaster University

- Margaret Gowing, CBE, FBA, FRS, holder of the first chair in the History of Science at Oxford

- Rom Harré, former Director of the Centre for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science at the London School of Economics

- Sir John Hicks, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics

- Ursula Hicks, economist and founder of The Review of Economic Studies

- Sir Paul Nurse, Nobel Prize–winning biochemist, former President of the Royal Society, Chancellor of the University of Bristol

- Michael Stumpf, Professor of Theoretical Systems Biology at Imperial College

- Henri Tajfel, former Chair of Social Psychology at the University of Bristol

- Michael J. Whelan, Professor in the Department of Materials at Oxford, and recipient of multiple awards for work in crystallography and microscopy including the Hughes Medal, the C.V. Boys Prize, and the Gjønnes Medal

Honorary fellows

Principals

- 1962–1988: John Bamborough, founding principal

- 1988–1996: Sir Bryan Cartledge

- 1996–2010: Paul Slack

- 2010–present: Nick Brown[57]

References

- ^ "Linacre College : Annual Report and Financial Statements : Year ended 31 July 2020" (PDF). p. 24. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Davies, Evan; Wagner, Eva (2005), Bamborough's Linacre: A Tribute to John Bernard Bamborough, ISBN 0970970056

- ^ a b c "Linacre College Oxford - Celebrating 50 years 1962-2012". Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Davies, Evan; Wagner, Eva (2005), Bamborough's Linacre: A Tribute to John Bernard Bamborough, ISBN 0970970056

- ^ "Statues of Linacre College" (PDF). Linacre College. 5 June 1986. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "Transformative Donation to College | Linacre College". www.linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Oxford college to change its name after £155m donation". The Guardian. 3 November 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ "Oxford college to receive £155m donation from Vietnamese company". BBC News. November 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ "Linarce College". University of Oxford. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Linacre College: Named Facilities". Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ "Accommodation | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "Instagram post by Linacre College • Nov 3, 2016 at 9:34am UTC". Instagram. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Gilbert Ryle Collection | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Linacre wins green award". Oxford University Gazette. 13 June 1996. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ a b "The 2010 Winners – BCE Environmental Leadership Awards" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ "College history | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Named Areas of College | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Unveiling of the Dancing Phoenix | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "Instagram post by Linacre College • Jun 20, 2017 at 9:58am UTC". Instagram. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "BEST PUBLIC BUILDING 2008". The Brick Development Association. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ "BEST CRAFTSMANSHIP AWARD 2008". The Brick Development Association. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ "Accommodation". Linacre College, Oxford. Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ "Sustainability | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Linacre: A Sustainable College | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Green Investment | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ Lalor, Doireann (20 May 2009). "Green Voices". Cherwell. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ Baraniuk, Chris (2 November 2007). "'Green Norrington' scrutinises colleges". Cherwell. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ Lim, Vicky (30 May 2011). "How green can you go?". Cherwell. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "Environment | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Linacre College Green Society". facebook.com. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Linacre Green Society". facebook.com. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Linacre Allotment Society". Facebook. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ Goodman, Jess (13 June 2006). "Saving the midnight oil". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ Jarda, Oliver (October 2008). "Did we need the sheep's clothing? Linacre sheds its carbon neutrality" (PDF). Linacre Common Room. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Linacre College Common Room | Societies | Green Society | 10:10 Campaign". crarchive.linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Linacre College: Carbon Reduction Strategy" (PDF). Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Oxford students drive £100,000 positive investment into clean, green energy". ethex.org.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ Planet, People &. "Fairtrade Universities | People & Planet". old.peopleandplanet.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ Wall, Joanna (3 March 2011). "Going bananas for Fairtrade". Cherwell. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ "The Linacre Banking Seminars" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ Davies, Evan; Wagner, Eva (2005), Bamborough's Linacre: A Tribute to John Bernard Bamborough, ISBN 0970970056

- ^ "The Linacre Lectures - Oxford Talks". talks.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "2017 Linacre Lecture | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Linacre College Annual Report and Financial Statements" (PDF). Linacre College. 31 July 2014. p. 9. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Linacre College | About Linacre | Events". 18 June 2014. Archived from the original on 18 June 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "Environmental Change Institute (ECI) - Oxford University". 10 June 2015. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "Tanner Lecture on Human Values 2019 | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ "2018 Tanner Lecture on Human Values | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ "2017 Tanner Lecture | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "2016 Tanner Lecture on Human Values | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Tanner Lecture 2015 | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Tanner Lecture 2014 | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Tanner Lecture 2013 | Linacre College". linacre.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "John Keown". kennedyinstitute.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Aitken, Jessica (24 August 2017). "Martin Aitken obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "Wing Commander Rupert Cecil". The Telegraph. London. 14 July 2004. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ Dr Nick Brown Archived 12 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Official website

- Common room website

- Virtual Tour of Linacre College (slightly out of date due to new building)