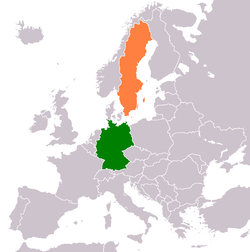

Germany–Sweden relations

| |

Germany |

Sweden |

|---|---|

The relation between Germany and Sweden has a long historical background.[1] The relationship is characterized by exchanges between the neighboring countries of the Baltic Sea in the 14th century.[2] Both countries are members of the European Union, United Nations, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Council of the Baltic Sea States and the Council of Europe.[3] Germany supports Sweden's NATO membership Germany currently has an embassy in Stockholm.[4] Honorary consuls are in Göteborg, Jönköping, Kalmar, Luleå, Malmö, Sälen, Uddevalla, Visby and Åmotfors.[5] The Swedish embassy in Germany is in Berlin. Honorary consuls are in Bremen, Düsseldorf, Erfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Hamburg, Hannover, Kiel, Leipzig, Lübeck-Travemünde, München, Rostock and Stuttgart.[6] About 50,000 Swedes live in Germany [1], and about 20,000 Germans live in Sweden. [2]

History

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2016) |

During the First World War (1914-1918) Sweden was neutral towards Germany. In the times of the Weimar Republic (1918-1933) Sweden was economically dependent on Germany. One of the important customer countries of Sweden in terms of iron ore was Germany. Moreover, a lot of German large companies acquired significant stock options of Swedish companies. In 1926 the trade and shipping treaty between the two countries was cancelled by Germany, because of disadvantages for German agrarian economy. In Sweden, the reorientation from German to Anglo- American culture had begun after the First World War. But still the upper classes of Sweden derived their culture and inspiration from the German universities, conservatories and art centers. In the interwar period the Swedish import of German literature had an important role.[7] The domestic political development of Germany, especially the rapid increase of the influence of National Socialists in the German policy after 1930, was followed with big interest by Sweden. The Swedish press adopted a distanced and critical attitude towards the National Socialism which caused disgruntlements between the German-Swedish relations. While Germany was influenced by National Socialism, Sweden was a country with social democratic government.

In autumn 1932 Hermann Göring (NSDAP) the president of the Reichstag, at that time, complained to Karl Albert Damgren, the press responsible of the Swedish delegation, in Berlin about the style of the reporting in the Swedish press in relation to National Socialism. The seizing power of Hitler and NSDAP at 30 January 1933 created still problems between Germany and Sweden. Frederic Hans von Rosenberg complained about a Swedish article in the “Social-Demokraten.” He said that the article contained wrong and exaggerated information. But Sweden was also attacked by German press. In the years that followed (1934-1937) the Swedish-German relations occurred a quiet phase. The German government circles expressed their interest in friendly contact with Sweden. Sweden declared in the Second World War again its neutrality. But Arvid Richert, the Swedish envoy in Berlin expressed his apprehension that Sweden could be involved in the war. He advised Sweden that they had to show resistance and attention in relation to statements about Germany to protect their country.[8]

The post war period of Sweden was characterized by continuity. From Sweden's point of view there was no need for analyzing of their behavior during the National Socialism. It did not need a construction of parliamentary democracy or a constitutional reform. But one of Sweden's strategies after the war was the rejection of all things which was associated with National Socialism. Thus militaristically and nationalistically currents were opposed and Anglo-American values of modernity and rationality were benefited. [9]

Political relations

Germany takes an important role in the Swedish foreign affairs because of its political and economic strength. The cooperation between the two countries becomes apparent in various sections. The bilateral relations are broadly problem-free. Early in year 2012 Reinfeldt was a guest of Chancellor Merkel. In May 2012 the German federal president Gauck visited Sweden at his trip. At autumn 2012 the federal ministers Schäuble and de Maizière went to Sweden, and in January 2017 Chancellor Angela Merkel visited Prime Minister Stefan Löven.[10][11]

Economic relations

On the one hand the main supplier country of Sweden is Germany. The amount of Sweden's imports from Germany is about 17.3 percent, from Norway about 8.7 percent and from Denmark about 8.4 percent. On the other hand, one of the main customer countries of Sweden is Germany. Sweden exports most of their products to Norway. But Germany is with an amount of 9.8 percent in the lead of Sweden's customer countries.[12] In year 2012 Germany imported goods from Sweden in the amount of 13 billion Euros.[13] Among the products which Sweden exports to Germany are pharmaceutical products (18.2%), paper and paperboard (18.3%), metals (12.5%), machines (8.8%), automobiles and automobile particles (7.7%), mineral ores (6.3%) and chemical products (4.6%). 18.2 percent of the total German exports to Sweden are automobiles and automobile particles, 14.5 percent machines, 9.5 percent EDP-appliances, 8.5 percent chemical products, 7.7 percent electrical equipment and 6.5 percent metals.[14]

The stock of the foreign direct investments of Sweden in Germany was around 15.243 Million Euros in year 2009, around 16.146 million Euros in year 2010 and around 16.183 Million Euros in year 2011. The stock of German foreign direct investments in Sweden was higher. The stock was around 16.336 million Euros in year 2009, around 20.096 million Euros in year 2010 and around 26.027 million Euros in year 2011.[15] The number of the engagement of German companies in Sweden is about 870, with about 50.000 employees and estimated annual sales around 30 milliard euros. Regional focus areas are Stockholm, Göteborg and Malmö.[16]

Social policy

Principally Germany has deep interest in socio-political achievements and developments in Sweden. The sections child care, family policy and also the commerce with handicapped person are at the top of interest. Bilateral relations could be registered in the sections labor market reform, professional training and nursing care insurance.[17] Right-wing populism has emerged in both countries.[18]

Cultural relations

Until the Second World War, Sweden along with the rest of the Nordic countries and the Low Countries was geared to the German linguistic and cultural area and was considered to fall under the "German sphere of influence". After the War a rapid reorientation followed to the Anglo-American area. The German language has been replaced by English as the second language, though it still retains its position as the most popular foreign language for school students - much ahead of Spanish, French, Finnish, Italian, Arabic, Turkish, Kurdish, Greek, and Russian. Besides Goethe-Institut and Deutsche Schule Stockholm, further partner schools are of concern for the support of the German language in Sweden. The German-language congregation abroad as well as German-Swedish associations make a positive contribution to the intervention of German culture in Sweden. German film productions are in Swedish cinema and Television quite successful, but historical topics are more in the foreground. German ensembles and artist are going regularly to Sweden because of theatrical performances. In the literariness, a high demand exists for German classics. There are from time to time articles in Swedish press about the living in Germany, especially in Berlin.[19]

German institutions, associations and projects in Sweden

- Embassy of Germany, Stockholm

- Goethe-Institut Stockholm

- German-Swedish Chamber of Commerce

- Germany Trade and Invest GmbH (GTAI)

- German National Tourist Board (Deutsche Zentrale für Tourismus e.V., Tyska Turistbyrån AB)

- Deutsche Schule Stockholm

- Deutsche Schule Göteborg

- German Church, Stockholm (St. Gertrude's Church)

- German Church, Gothenburg (Christina Church)

- German Church, Malmö

- ARD German Radio & TV

- Friedrich Ebert Foundation

- German Wine Institute

- Deutsche Vereinigung Stockholm[citation needed]

- Svensk-Tyska Föreningen

- Deutscher Damenklub[citation needed]

- Deutscher Hilfsverein[citation needed]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft Stockholm[20][21]

Swedish institutions, associations and projects in Germany

References

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-11-11. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-11-27. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Hans Karl Gunther. German-Swedish relations. 1933-1939: The background for Swedish neutrality. Stanford 1954. p. 139.

- ^ Axel Huckstorf. Internationale Beziehungen 1933-1939: Schweden und das dritte Reich. Frankfurt am Main. 1997. P. 9-98. ISBN 3-631-31788-3

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Prime Minister to receive German Chancellor Angela Merkel". 19 January 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-17. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Schwedens Export-Partner Nummer 1 ist jetzt Norwegen". 28 February 2013.

- ^ "404". 11 January 2021.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-17. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

- Almgren, Birgitta. "Swedish German associations: Target for Nazi infiltration." Historisk Tidskrift (2015) 135#1 pp: 63–91.

- Ekman, Stig, Klas Åmark and John Toler, eds. Sweden’s Relations with Nazism, Nazi Germany and the Holocaust: A Survey of Research (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International, 2003)

- Fritz, Martin. "Swedish ball-bearings and The German war economy." Scandinavian Economic History Review (1975) 23#1 pp: 15–35.

- Fritz, Martin. German steel and Swedish iron ore, 1939-1945 (Institute of Economic History of Gothenburg University, 1974)

- Gilmour, John. Sweden, the Swastika, and Stalin: The Swedish Experience in the Second World War (Edinburgh University Press, 2010)

- Hägglӧf, M. Gunnar. “A Test of Neutrality: Sweden in the Second World War” International Affairs (April, 1960) 36#2 pp: 153–167.

- Jonas, Michael. "Activism, Diplomacy and Swedish–German Relations during the First World War." New Global Studies (2014) 8#1 pp: 31–47.

- Levine, Paul A. Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest: Myth, History and Holocaust (London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2010)

- Persson, Mathias. "Mediating the Enemy: Prussian representations of Austria, France and Sweden during the Seven Years War." German History (2014) 32#2 pp: 181–200.

- Phillips, Jason C. "The Forgotten Footnote of the Second World War: An Examination of the Historiography of Scandinavia during World War II." (Dissertation 2013). online

- Winton, Patrik. "Sweden and the Seven Years War, 1757–1762: War, Debt and Politics." War in history (2012) 19#1 pp: 5-31.