Whaling

Whaling is the activity of harvesting whales that dates back to at least 6,000 BC. Initially, hunters pursued whales for both whale oil and food. However, modern whaling primarily has commercial value as a protein source. The ease with which the large, slow moving whales are captured coupled with a previous long-term, lack of effective international animal husbandry regulations over the activity had driven down some whale populations to the alarm of many countries and numerous conservation groups. The potential for the extermination of species by whaling has set up a heated debate over the value of whaling in modern society. While there is no broad international consensus regarding modern whaling, commercial whaling is currently still subject to a moratorium by the IWC, However, at the 2006 IWC meeting, the St Kitts and Nevis declaration St_Kitts_and_Nevis_Declaration was adopted by a slim majority of the members. Whaling and other threats have led to at least 5 of the 13 great whales being listed as endangered. [1] [2] [3] [4]

History of whaling

It is unknown when humans began hunting whales. The earliest archaeological record of whaling is found in South Korea where carved drawings, dating back to 6,000 BC, show that Stone Age people hunted whales using boats and spears.[1] However, over time, whaling techniques have grown more technologically sophisticated. Initially, whaling was confined to (near) coastal water, such as the Basque fishery targeting the Atlantic Northern Right Whale around 15th to 18th century and the Atlantic Arctic fishery around and in between Spitzbergen and Greenland from around the 17th to the 20th century. However, after the emergence of modern whaling techniques, certain species of whale started to be seriously affected by whaling. These techniques were spurred in the 19th century by the increase in demand for whale oil,[2] and later in the 20th century by a demand for whale meat.

Whaling history has affected both the development of many cultures as well as their environment.[3]

Japan

Harpooning of whales by hand began in Japan in the 12th century, but it was not until the 1670s, when a new method of catching whales using nets was developed, that whaling really began to spread throughout Japan. In the 1890s Japan followed international trends, first switching to modern harpoon whaling techniques, and eventually to factory ships for mass whaling. In the postwar 1940s and 1950s, whale meat became a primary source of food and protein in Japan following the famines that came with World War II. In many whaling nations, the discovery of petroleum products that could replace the industrially important parts of whales, such as the oil, resulted in a decline in the importance and levels of whaling. This was not the case in Japan, however, where whale meat was seen to be important food source, and where the whaling industry was a source of pride.

United States

The whaling history of the United States can be roughly divided into two parts: native whaling and commercial whaling (though overlaps exist). Native whaling is a tradition which reaches back to the early Inuit of North America hundreds of years before the colonization by Europeans.[4] Commercial whaling in the United States was the centre of the world whaling industry during the 18th and 19th centuries and was most responsible for extinction or near-extinction of certain species of whales. New Bedford, Massachusetts and Nantucket Island were the primary whaling centres in the 1800s. In 1857, New Bedford had 329 registered whaling ships. Prior to the 1920s when commercial whaling in the United States waned, as petroleum products began replacing oil derived from whales, numerous fishing ports were actually whaling ports which built whaling ships. From the enormous US whaling fleet of the 1800s in the US, only one wooden ship remains, the Charles W. Morgan, berthed at Mystic Seaport in Mystic, Connecticut.

The primary focus of whaling in the United States was the lamp oil made from the prodigious amount of fat contained in whales. The whaling ships carried rendering equipment which rendered fat from the carcasses as soon as it was raised onto the ships. Aside from the fat and certain bones, the majority of carcass was generally thrown back in the water, as there was no market for whale meat. Whale oil was, at that time, the highest quality oil for lamps.

The discovery of petroleum in Titusville, Pennsylvania, on August 27, 1859 by Edwin L. Drake was the beginning of the end of commercial whaling in the United States as kerosene, distilled from crude oil, replaced whale oil in lamps. Later, electricity gradually replaced oil lamps, and by the 1920s, the demand for whale oil had disappeared entirely.

Today, the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park commemorates the heritage of both commercial and native whaling in the United States at its locations in New Bedford and Barrow, Alaska.

Modern whaling

Whale oil is little used today, thus modern whaling has primarily commercial value as a protein source. The primary species hunted is the Minke Whale, the second smallest of the baleen whales. Recent scientific surveys estimate a population of 180,000 in the central and North East Atlantic and 700,000 around Antarctica.

International cooperation on whaling regulation started in 1931 and a number of multi-lateral agreements now exist in this area, the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) of 1946 being the most important. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) was founded by the ICRW for the purpose of giving management advice to the member nations on the basis of the work of the Scientific Committee. Countries which are not members of IWC are not bound by its regulation and conduct their own management programs.

The members of the IWC voted on 23 July 1982 to enter into a moratorium on all commercial whaling beginning in the 1985-86 season. Since 1992, the IWC Scientific Committee has requested of the IWC that it be allowed to give quota proposals for some whale stocks, but this has so far been refused by the IWC. Norway legitimately continues to hunt Minke Whales commercially under IWC regulation, as it has lodged an objection to the moratorium.

Canada

Canada left the IWC in 1982 and as such is not bound by the moratorium on whaling. Canadian whaling is carried out by various Inuit groups around the country in small numbers and is managed by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. The meat obtained from these whaling are commercially sold through shops and supermarkets. There is considerable consternation amongst conservationists about the hunt. The Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society says "Canada has pursued a policy of marine mammal management which appears to be more to do with political expediency rather than conservation."

Caribbean whaling

Some whaling is conducted from Grenada, Dominica and Saint Lucia. Species hunted are the Short-finned Pilot Whale, Pygmy Killer Whale and Spinner Dolphins. Throughout the Caribbean, around 400 Pilot Whales are killed annually with the meat being sold locally. The hunting of small cetaceans is not regulated by the IWC.

Faroe Islands

Grindadráp is whaling in the Faroe Islands and has been practised since at least the 10th century. It is strongly regulated by Faroese authorities and is approved by the International Whaling Commission. The hunts are "regulated" by the division of the Faroe Islands into 11 whaling districts, with a total of 23 authorised whaling bays. Around 950 Long-finned Pilot Whales (Globicephala melas) are harvested throughout the year. The hunt mainly takes place during the summer, are non-commercial, and anyone can participate. Grindadráp works by surrounding the whales and dolphins with a wide semi-circle of boats and slowly driving them into a bay or fjord and then onto a beach.

Greenland

Greenland Inuit whalers kill around 170 whales per year, making them the third largest hunt in the world after Norway and Japan, though their take is only about one quarter of either Japan's or Norway's, which take 600 or more whales each year. The IWC treats the west and east coasts of Greenland as two separate population areas and sets separate quotas for each coast. The far more densely populated west coast accounts for over 90% of individuals caught. In a typical year around 150 Minke and 10 Fin Whales are taken from west coast waters and around 10 Minkes are from east coast waters.

Iceland

Unlike Norway, Iceland did not lodge an objection against the IWC moratorium, which came into force in 1986. Between 1986 and 1989 around 60 animals per year were taken under a scientific permit. However, under strong pressure from anti-whaling countries, viewing scientific whaling as a circumvention of the moratorium, Iceland ceased whaling altogether in 1989. Following the 1991 refusal of the IWC to accept its Scientific Committee's recommendation to allow sustainable commercial whaling, Iceland left the IWC in 1992.

Iceland rejoined the IWC in 2002 with a reservation to the moratorium. This reservation is not recognized by anti-whaling countries. In 2003 Iceland resumed scientific whaling. Iceland presented a feasibility study to the 2003 IWC meeting to take 100 Minke, 100 Fin, and 50 Sei in each of 2003 and 2004. The primary aim of the study was to deepen the understanding of fish-whale interactions - the strongest advocates for a resumed hunt are fisherman concerned that whales are taking too many fish. The hunt was supported by three-quarters of the Icelandic population. Amid concern from the IWC Scientific Committee about the value of the research and its relevance to IWC objectives ("Recent Icelandic Proposal" at the International Whaling Commission website), no decision on the proposal was reached. However under the terms of the convention the Icelandic government issued permits for a scientific catch. In 2003, Iceland took 36 Minke Whales from a quota of 38. In 2004, it took 25 whales (the full quota). In 2005, the government issued a permit for a third successive year - allowing whalers to take up to 39 whales.

Iceland resumed commercial whaling in 2006. The annual quota is set to 30 Minke Whales (out of an estimated 174,000 animals in the North Atlantic [5]) and nine Fin Whales (out of an estimated 30,000 animals in the North Atlantic [5][6]). Iceland broke the IWC ban on commercial whaling on 22 October 2006 after Icelandic fishermen killed a sixty ton female Fin Whale.[7]

Indonesia

Lamalera, on the south coast of the island of Lembata, and Lamakera on neighbouring Solor are the last two remaining Indonesian whaling communities. The hunters have religious taboos that ensure that they use every part of the animal. About half of the catch is kept in the village; the rest is traded in local markets, using barter. In 1973, the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) sent a whaling ship and a Norwegian master whaler, to modernize their hunt. This effort lasted three years, and was not successful. According to the FAO report, the Lamalerans "have evolved a method of whaling which suits their natural resources, cultural tenets and style." [8]

Japan

When the commercial whaling moratorium was introduced by the IWC in 1982, Japan lodged an official objection, but withdrew this objection in 1987 after the United States threatened it with sanctions. Thus, Japan became bound by the moratorium, unlike Norway, Russia and (more disputed) Iceland. Therefore, in 1987, Japan stopped commercial whaling activities in Antarctic waters, but in the same year began a controversial scientific whaling program (JARPA - Japanese Research Program in Antarctica). JARPA continued until 2005, but was immediately replaced by a new program called JARPA II. Catches of Antarctic minke whales under JARPA II have doubled (from 440 to 880 a year, plus or minus 10%), and beginning in 2007/08 will add takes of 50 fin and 50 humpback whales a year.

The Japanese government mainly justifies this type of whaling by asserting that; analysis of stomach contents provides insight into the dietary habits of whales, analysis of whale ear plugs is the only accurate way to ascertain the age of a whale, the degree of interbreeding in the population can only be ascertained from tissue samples and examination of whale ovaries is required in order to determine the age of sexual maturity. However, this approach has been criticized by many scientists on the International Whaling Commission's Scientific Committee (see Clapham et al. 2006, Marine Policy doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2006.09.004).

Japan's scientific whaling program has remained controversial, with anti-whaling groups maintaining that the killing of whales is unnecessary for scientific purposes and that the real reason for the scientific kills is to provide whale meat for Japanese restaurants and supermarkets. Countries opposed to whaling have raised similar concerns and passed non-binding resolutions in the IWC urging Japan to stop this program. The Japanese government points out that hunting of whales for research purposes is specifically sanctioned under IWC regulations and that those regulations specifically require that whale meat be fully utilized upon the completion of research.

In 1994, Australia attempted to stop some of the Japanese whaling program by enforcing a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around the Australian Antarctic Territory. However, Antarctic territories are not generally recognized internationally. In particular, the Antarctic Treaty, to which Australia is a signatory, specifically states that all claims to Antarctic territories remain unresolved while the treaty is in force (the treaty was originally devised to prevent conflict between the USSR and USA during the Cold War). Legal advice obtained by the Australian government indicated that attempts to stop Japanese whaling in the Australian Antarctic Territory by resorting to international courts may, in fact, have led to Australia losing its claim to that territory.

In 2002, Japanese whalers took five Sperm, 39 Sei, 50 Bryde's and 150 Minke Whales in the northern catch area and 440 Minke whales in the southern catch area. The catch was carried out under the IWC's special license for whaling research. In 2005 Japan announced that they would significantly expand their whaling. With the adoption of this plan, Japan’s lethal take will include 100 Sei Whales, 10 Sperm Whales, 50 Humpback Whales, 50 Fin Whales, and 50 Bryde’s Whales, some of which are considered endangered, along with 1,155 Minke Whales which are not classified as endangered.

The most vocal opponents of the Japanese push for a resumption of commercial whaling are Australia and the United States, whose stated purpose for opposing whaling is the need for conservation of endangered species.

- See also: International Whaling Commission for more details on controversy surrounding the Japanese whaling program.

Norway

| Year | Quota | Catch |

| 1994 | 319 | 280 |

| 1995 | 232 | 218 |

| 1996 | 425 | 388 |

| 1997 | 580 | 503 |

| 1998 | 671 | 625 |

| 1999 | 753 | 591 |

| 2000 | 655 | 487 |

| 2001 | 549 | 550 |

| 2002 | 671 | 634 |

| 2003 | 711 | 646 |

| 2004 | 670 | 541 |

| 2005 | 797 | 639 |

| 2006 | 1052 | 546 |

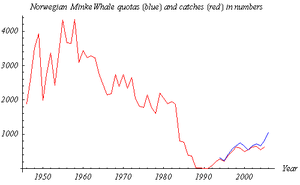

Norway has registered an objection to the International Whaling Commission moratorium, and is thus not bound by it. In 1993, Norway resumed a commercial catch, following a period of five years where a small catch was made under a scientific permit. The catch is made solely from the Northeast Atlantic Minke Whale population, which is estimated to consist of about 110,000 animals. Norwegian Minke Whale catches have fluctuated between 503 animals in 1997 to 546 in 2006.

Prior to the moratorium, Norway caught around 2,000 Minkes per year. The North Atlantic hunt is divided into five areas and usually lasts from early May to late August. Norway exports a limited amount of whale meat to the Faroes and Iceland. It has been attempting to export to Japan for several years, though this has been hampered by legal protests and concerns in the Japanese domestic market about the effects of pollution in the blubber of the North Atlantic Minke whale.

In May 2004, the Norwegian Parliament passed a resolution to considerably increase the number of Minkes hunted each year. The Ministry of Fisheries also initiated a satellite tracking programme of various whale species to monitor migration patterns and diving behaviour. The tagging research program has been underway since 1999 [9]

Russia

Russians in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug in the Russian Far East are permitted under IWC regulation to take up to 140 Gray Whales from the North-East Pacific population each year.

United States

In the United States whaling is carried out by Alaska natives from nine different communities in Alaska. The whaling programme is managed by the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission which reports to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The hunt takes around 50 Bowhead Whales a year from a population of about 8,000 in Alaskan waters. Conservationists fear this hunt is not sustainable, though the IWC Scientific Committee, the same group that provided the above population estimate, projects a population growth of 3.2% per year. The hunt also took an average of one or two Gray Whales each year until 1996. The quota was reduced to zero in that year due to concerns about sustainability. A review set to take place in the future may result in the hunt being resumed.

The Makah tribe in Washington State also reinstated whaling in 1999, despite intense protests from animal rights groups.

Bycatch and illegal trade

Since the IWC moratorium, there have been several instances of illegal whale kills by IWC nations. In 1994, the IWC reported evidence from genetic testing [10] of whale meat and blubber for sale on the open market in Japan in 1993. [11] In addition to the legally-permitted minke whale, the analyses showed that the 10-25% tissues sample came from non minke, baleen whales species, neither of which were then allowed for take under the IWC rules. Further research in 1995 and 1996 shows significant drop of non-minke baleen whales sample to 2.5%. [12] In a separate paper, Baker stated that "many of these animals certainly represent a bycatch (incidental entrapment in fishing gear)" and stated that DNA monitoring of whale meat is required to adequately track whale products. [13]

It was revealed in 1994 that the Soviet Union had been systematically underreporting the number of whales it took. For example, from 1948 to 1973, the Soviet Union killed 48,477 Humpback Whales rather than the 2,710 it officially reported to the IWC. [14] On the basis of this new information, the IWC stated that it would have to rewrite its catch figures for the last forty years. [15] According to Ray Gambell, the Secretary of the IWC at the time, the organisation had raised its suspicions of underreporting with the former Soviet Union, but it did not take further action because it could not interfere with national sovereignty. [16]

In 1985, an activist organization, Earthtrust, placed undercover employees on Korean fishing vessels who took photographs of both fin and right whales being hunted and processed in violation of the ban.[17]

The arguments for and against whaling

Conservation status

The sharpest point of debate over whaling today concerns the conservation status of hunted species. Today there is widespread agreement around the world that it is morally wrong to exterminate a species of animal. The unregulated whaling before IWC introduced regulation and ban had depleted a number of whale populations to a significant extent and several whales species were severely endangered. Past ban on these species of whales which were implemented around 1960s has helped some of these species to recover, according to IUCN's Cetacean Specialist Group (CSG).

"Several populations of southern right whales, humpbacks in many areas, grey whales in the eastern North Pacific, and blue whales in both the eastern North Pacific and central North Atlantic have begun to show signs of recovery." [18]

Other species, however, in particular the Minke Whale, have never been considered endangered and still other species or certain population group within particular whales species have shown signs of recovery.

Still, those opposed to whaling argue that a return to full-scale commercial whaling will lead to economic concerns overriding those of conservation, and there is a continuing battle between each side as to how to describe the current state of each species. For instance, conservationists are pleased that the Sei Whale continues to be listed as endangered but Japan says that the species has swelled in number from 9,000 in 1978 to about 28,000 in 2002 and so its catch of 50 Sei whales per year is safe, and that the classification of endangered should be reconsidered for the North Pacific population.

Some North Atlantic states have argued that Fin Whales should not be listed as endangered any more and criticize the list for being inaccurate.[19] IUCN has recorded studies showing that more than 40,000 individuals are present in the North Atlantic Ocean around Greenland, Iceland, and Norway.[20] As there is no information about Fin Whales in areas outside of the Northern Atlantic where they still hold the status of being endangered.

A complete list of whale conservation statuses as listed by The World Conservation Union (IUCN) is given below. Note that, in the case of Blue and Gray Whales, the IUCN distinguishes the statuses of various populations. These populations, while not regarded as separate species, are considered sufficiently important with respect to conservation.[21][22]

| Extinct | Critically Endangered | Endangered | Vulnerable | Lower Risk (Conservation Dependent) |

Lower Risk (Near Threatened) |

Lower Risk (Least Concern) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

None IUCN |

Gray Whale |

|

|

Additionally, the IUCN notes that the Atlantic population of Gray Whales was made extinct around the turn of the eighteenth century.[23]

Method of killing

Farming whales in captivity has never been attempted and would almost certainly be logistically impossible. Instead, whales are killed at sea often using explosive harpoons,[24] which puncture the skin of a whale and then explode inside its body. Anti-whaling groups say this method of killing is cruel, particularly if carried out by inexperienced gunners, because a whale can take several minutes or even hours to die. In March 2003, Whalewatch, an umbrella group of 140 conservation and animal welfare groups from 55 countries published a report, Troubled Waters, whose main conclusion was that whales cannot be guaranteed to be killed humanely and that all whaling should be stopped. They quoted figures that said 20% of Norwegian and 60% of Japanese-killed whales failed to die as soon as they had been harpooned. John Opdahl of the Norwegian embassy in London responded by saying that Norwegian authorities worked with the IWC to develop the most humane killing methods. He said that the average time taken for a whale to die after being shot was the same as or less than that of animals killed by big game hunters on safari. Whalers also say that the free-roaming lifestyle of whales followed by a quick death is less cruel than the long-term suffering of factory-farmed animals.

In response to the UK's opposition to the resumption of commercial whaling on the grounds that no humane method of killing whales exists, or "is on the horizon", the pro-whaling High North Alliance points to apparent inconsistencies in the policies of some anti-whaling nations by drawing comparisons between commercial whaling and recreational hunting. For instance, the United Kingdom allows the commercial shooting of deer without these shoots adhering to the standards of British slaughterhouses, but says that whalers must meet these standards as a pre-condition before they would support whaling. Moreover, fox hunting, in which foxes are mauled by dogs, is legal in many anti-whaling countries including Ireland, the United States, Portugal, Italy and France (although not in the UK) according to UK Government's Burns Inquiry (2000). Pro-whaling nations argue that they should only have to adhere to the lowest standards (such as for the UK Red Deer hunts), and draw the conclusion that whales are the equivalents of cows in India and the cruelty argument is a mere expression of cultural bigotry, similar to the Western attitude towards the eating of dog meat in several East Asian countries.[25]

The economic argument

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|section|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

The anti-whaling side of the argument often argues that the killed whales are those that are most curious about boats and thus the easiest to approach and kill. However, these individuals are also the most valuable to the whale-watching industry in coastal areas, as these "friendly" whales represent the easiest means of providing an experience to their customers. The argument over whether whales are worth more dead than alive is primarily raised by anti whaling side while pro whaling side consider it to be spurious.

The whale watching industry, and those opposed to whaling on moral grounds, claim that once all benefits to local economies such as hotels, restaurants and other tourist amenities are factored in, and the fact that a whale can only be killed once but watched many times, the economic balance weighs firmly down on the side of not hunting whales. This economic argument is a particular bone of contention in Iceland, which has among the most-developed whale-watching operations in the world and where hunting of Minke Whales began again in August 2003. The argument is less applicable to the Antarctic waters as Minke Whales are more abundant there, and there are far fewer whale-watching cruises. Many developing countries such as Brazil, Argentina and South Africa argue that whale watching, a growing billion-dollar industry, provides more revenue and more equitable distribution of profits than the possible resumption of commercial whaling by pelagic fleets from far-away developed countries. These countries are defending their right to the non-lethal use of whale resources and refuse to bow down to the pressures of the whaling industry to allow the resumption of commercial whaling in their regions. Aside from Indonesia, no country in the Southern Hemisphere is currently whaling or intends to, and proposals to permanently forbid whaling South of the Equator are defended by the above mentioned developing countries as well as Peru, Uruguay, Australia, and New Zealand, which strongly object to the continuation of Japanese whaling in the Antarctic.

The pro-whaling side claims that the debate is moot. They point out that the anti whaling argument implies that hunt is done on unsustainable basis to the point that it deprives the whale watching industry of whales. Therefore the context of the debate itself is slanted toward anti-whaling rhetoric. Whalers argue that if whales are hunted on a sustainable basis, the argument that the whale-watching industry and whaling industry is in competition is invalid. Moreover, given the size of sea, a simple system of communication between any whaling fleet and whale watching boats would ensure that these activities are separated. Whaling and its associated activities continue to provide employment and economic stimulant for fishery, logistic, restaurant and other related industries. Whale blubber can be converted into valuable oleochemicals while the unused portions of the whale carcass can be rendered into meat and bone meal.

The pro-whaling side has no objection to use of whales as tourist attractions which is another way to utilise whales as a resource. Moreover, whalers argue that it is unfair for the whale watching industry to prevent whaling provided that it is done on sustainable ground. Moreover, for poorer whaling nations, the need for resumption of whaling is more pressing. Horace Walters, from the Eastern Caribbean Cetacean Commission stated, "We have islands which may want to start whaling again - it's expensive to import food from the developed world, and we believe there's a deliberate attempt to keep us away from our resources so we continue to develop those countries' economies by importing from them. "[26]

Anti-whaling groups claim that developing countries which support a pro-whaling stance may hurt their tourism industry. In reference to pro whaling Caribbean islands, Joth Singh, director of wildlife and habitat for the International Fund for Animal Welfare, stated "Individuals for whom whaling is abhorrent will think twice about going to a destination where their values are not shared." This position is echoed by governments opposed to whaling. Britain's environment minster, Ben Bradshaw stated "There can be a backlash by British consumers,". Danielle Grabiel, American observer of the IWC from the Environmental Investigation Agency, also stated "Americans feel very strongly about their love for the whales, and I wouldn't be surprised if they decided not to see their money go to countries that support a return to commercial whaling," Saint Lucia's fisheries chief, Ignatius Jean, in response stated "We have heard these threats before, but we will not cower,". Still, The Dominica Hotel and Tourism Association called for "Caribbean governments to abandon pro-whaling positions and to propose a new regional whale sanctuary to promote the fast-growing pastime of whale watching."

Intelligence

The issue of the extent of whale intelligence has also been debated, primarily by those opposed to commercial whaling. The idea is that it is unethical to eat intelligent animals, as they are closer to humankind than other animals. Some scientists believe that whales' intelligence levels are on par with those of humans , but the current state of scientific research does not provide a consensus for such a claim though some research has shown that whales are highly "social" animals ( [5]). How to classify animals by intelligence is a different issue, but this issue has been overshadowing the question related to if it is unethical to eat intelligent animals or not.

Most of the research on cetacean intelligence has consisted of behavioural inference tests carried out on dolphins. Bottlenose Dolphins, for example, are able to recognize their own images in a mirror. However, in other research, they scored lower than ferrets in a test of learning set formation. Generally, both dolphin and pig intelligence is rated as higher than that of dogs. On the other hand, it is nearly impossible to duplicate these types of tests for whales.

Regardless, many anti-whaling campaigners claim that cetaceans are still among the most intelligent of all non-humans, and it is therefore morally wrong to kill them for food. However, those in favour of whaling point out that pigs are also amongst the most intelligent of animals with no definitive study indicating that whales are more intelligent than pig. Then it is inconsistent to claim that pigs can be used for food, and whales not, all other considerations notwithstanding. Thus, in the view of pro-whalers, if the slaughter and consumption of another "intelligent" land animal is a non-issue, then similarly, protestations against the slaughter and consumption of whales cannot logically be ground on the basis of intelligence. Moreover, this apparent inconsistency is seen as another indication that anti whaling argument is rooted in cultural prejudice.

Further, it is philosophically questionable as to whether the intelligence of an animal is a valid measure of the ethical acceptability of killing it. A logical extension of this belief would be to suggest that within a species, individuals who are more intelligent have more right to life. This would be considered entirely immoral in a human society. According to this argument, the intelligence of an animal should not be considered when deciding whether or not it is ethical to kill it for food. It is important, however, to discriminate between 'intelligence' and other factors that may affect the ability of the animal to experience pain and suffering, such as the possession of a complex central nervous system which almost all mammals possess.

Safety of eating whale meat

Studies of several species have shown that whale meat products often contain pollutants such as PCBs, mercury, and dioxins. [27][28] An analysis of commercially sold whale meat in Japan found similar results. Studies on the red meat and blubber of Long-finned Pilot Whales in the Faroe islands show high toxin levels and studies have shown that this has had a detrimental effect on those who eat the red meat and blubber. [29][30] However, studies of Minke Whales hunted in both the North Atlantic and the southern ocean have shown that the red meat of some Minke Whale individuals have levels of toxicity below recommended limits, with the Antarctic Minke having the lowest levels of contamination.[31]

In general, studies have shown that levels of some pollutants in toothed whale products are higher than corresponding levels in baleen whales [32], reflecting the fact that toothed whales feed at a higher trophic level than baleen whales in the food chain. Other contaminants such as the organochloride pesticides HCH and HCB also have higher levels in toothed species over baleen species, although Minke Whales had higher levels than most other baleen species.[27] In Norway, only the red meat of Minke Whales is eaten and studies indicate that average toxicity levels conform to national limits for toxicity [33][34]

Fishing

Whalers say that whaling is an essential condition for the successful operation of commercial fisheries, and thus the plentiful availability of food from the sea that consumers have become accustomed to. This argument is made particularly forcefully in Atlantic fisheries, for example the cod-capelin system in the Barents Sea. A Minke Whale's annual diet consists of 10 kilograms of fish per kilogram of body mass,[35] which puts a heavy predatory pressure on commercial species of fish. Thus, whalers say that an annual cull of whales is needed in order for adequate amounts of fish to be available for humans. Anti-whaling campaigners say that the pro-whaling argument is inconsistent: if the catch of whales is small enough not to negatively affect whale stocks, it is also too small to positively affect fish stocks. To make more fish available, they say, more whales will have to be killed, putting populations at risk. Additionally, often whale feeding grounds and commercial fisheries do not overlap.

Professor Daniel Pauly[36], Director of the Fisheries Center at the University of British Columbia weighed into the debate in July 2004 when he presented a paper to the 2004 meeting of the IWC in Sorrento. Pauly's primary research is the decline of fish stocks in the Atlantic, under the auspices of the Sea Around Us Project. This report was commissioned by Humane Society International, an active anti-whaling lobby. The report stated that although cetaceans and pinnipeds are estimated to eat 600 million tonnes of food per year, compared with just 150 million tonnes eaten by humans (These are Pauly's figures. Researchers at the Institute for Cetacean Research gave figures of 90 million tonnes for humans and 249-436 million tonnes for cetaceans. ), the type of much of the food that cetaceans eat (in particular, deep sea squid and krill) is not consumed by humans. Moreover, the reports says, the locations where whales and humans catch fish only overlap to a small degree. In an interview with the BBC, Pauly stated that:

The bottom line is that humans and marine mammals can co-exist. There's no need to wage war on them in order to have fish to catch. And there's certainly no cause to blame them for the collapse of the fisheries. It's really cynical and irresponsible for Japan to claim that the developing countries would benefit from a cull of marine mammals. It's the rich countries that are sucking the fish out of the poor countries' own seas.

— Daniel Pauly, BBC

In the report Pauly also considers more indirect effects of whales' diet on the availability of fish for fisheries. He continues to conclude that whales are not a significant reason for diminished fish stocks.

However, the dietary behaviour of whales differ among species as well as season, location and availability of prey. For example, Sperm Whales' prey primarily consists of mesopelagic squid. However, in Iceland, they are reported to consume mainly fish.[37] In addition to krill, Minke Whales are known to eat a wide range of fish species including capeline, herring, sand lance, mackerel, gadoids, cod, saithe and haddock.[38] Minke Whales are estimated to consume 633,000 tons of Atlantic herring per year in part of Northeast Atlantic [39]. In the Barents Sea, it is estimated that a net economic loss of five tons of cod and herring per fishery results from every additional Minke Whale in the population due the fish consumption of the single whale.[40]

See also

- International Whaling Commission

- North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission

- Institute of Cetacean Research, Japan

- Fisheries management

- Fishery

- New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park

- Seal hunting

- Sandefjord Museum, whaling museum

- History of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

References

- ^ "Rock art hints at whaling origins". BBC News. 2004-04-20. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "From Old Dartmouth to Modern New Bedford". New Bedford Whaling Museum. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ Douglas, M. S. V. (2004). "Prehistoric Inuit Whalers affected Arctic Freshwater Ecosystems". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101 (6): 1613–1617. doi:10.1073/pnas.0307570100.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Huntington, Henry (June 1992). "Alaska Eskimo Whaling". Retrieved 2006-12-03.

{{cite web}}: Text "publisher Inuit Circumpolar Conference" ignored (help) - ^ a b "Whale Population Estimates". International Whaling Commission. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "Iceland to resume commercial whaling hunts". Reuters. 2006-10-17. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Iceland breaks ban on whaling". BBC News. 2006-10-21. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Bruemmer, Fred (2001). "Sea hunters of Lamalera". Natural History. 110 (8). Natural History: 54–59.ISSN 0028-0712

- ^ "Norway. Progress report on cetacean research, January 2001 to December 2001, with statistical data for the calendar year 2001" (PDF). International Whaling Commission. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ Baker, Scott. Report to the International Whaling Commission (1994)

- ^ Baker, C. S. (1994). "Which Whales are Hunted? A Molecular Genetic Approach to Monitoring Whaling". Science. 265 (5178): 1538–1539. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Palumbi, S. R. (1998). "Species identification using genetic tools: The value of nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequences in whale conservation" (PDF). The Journal of Heredity. 89 (5): 459–464. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Modern Whaling" (PDF). 2002. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Angier, Natalie (1994-09-13). "DNA Tests Find Meat of Endangered Whales for Sale in Japan". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hearst, David (1994-02-12). "Soviet Files Hid Systematic Slaughter of World Whale Herds". Gazette (Montreal).

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Williams, David (1994-02-23). "We Didn't Know About the Whale Slaughter". Agence Fr. Presse.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Korean Pirate Whaling Expose (1985)". Earthtrust. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ^ "Extinction nears for whales and dolphins". BBC News. 2003-05-14. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Um stofnstærðir langreyðar og hrefnu við Ísland og flokkun IUCN". Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ^ "Red List of Threatened Species - Balaenoptera physalus". IUCN. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ^ "Red List of Threatened Species - Balaenoptera musculus (North Atlantic stock}". IUCN. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ^ "Red List of Threatened Species - Balaenoptera musculus (North Pacific stock}". IUCN. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ^ "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species - Eschrichtius robustus". IUCN. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ^ See also Bomb lance patents.

- ^ "Behind UK Whale Position Lurks Unregulated Commercial Deer Hunt". High North Alliance. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ^ "Spectrum of opinion at whaling meeting - A question of food". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ^ a b Simmonds, M. P. (2002). "Human health significance of organochlorine and mercury contaminants in Japanese whale meat" (PDF). Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 65: 1211–1235. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hobbs, K. E. "Levels and patterns of persistent organochlorines in minke whale (Balaenoptera acutostrata) stocks from the North Atlantic and European Arctic" (PDF). Environmental Pollution. 121 (2). Elsevier Science: 239–252. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Athanasiadou, Maria (2002). "Hydroxylated PCB Metabolites and PCBs in Serum from Pregnant Faroese Women". Environmental Health Perspectives. 110.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ {{cite journal | last = Dam | first = Maria | coauthors = Bloch, D. | date = 2000 | title = Screening of Mercury and Persistent Organochlorine Pollutants in Long-Finned Pilot Whale (Globicephala melas) in the Faroe Islands | journal = Marine Pollution Bulletin | volume = 40 | issue = 12 | id = DOI 10.1016/S0025-326X(00)00060-6 | pages = 1090-1099}

- ^ "Til þeirra sem málið varðar" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ^ Endo, Tetsuya (2005). "Total Mercury, Methyl Mercury, and Selenium Levels in the Red Meat of Small Cetaceans Sold For Human Consumption in Japan". Environmental Science and Technology. 39 (15). American Chemical Society: 5703–5708.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Schweder, Tore (2001). "Protecting whales by distorting uncertainty : non-precautionary mismanagement?". Fisheries Research. 52 (3): 217–225. ISSN 0165-7836.

- ^ Hassauer, Dr. Martin (April 2002). "Evaluation of contaminants in meat and blubber of Minke Whales" (PDF). Greenpeace. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sigurjonsson and Vikingsson, 1997

- ^ "Dr. Daniel Pauly". Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ^ Sigurjónsson, et al 1998

- ^ Haug et al, 1996

- ^ Folkow et al, 1997

- ^ Schweder, et al, 2000

General references

Books

- Melville, H., The Whale. London: Richard Bentley, 1851 3 vols. (viii, 312; iv, 303; iv, 328 pp.) Published October 18 1851. (later re-published in New York as Moby-Dick)

- Muller, C. G., (2006). Echoes in the Blue. Koru Press. ISBN 9780615135946

- Day, D., (1997). The Whale War. Sierra Club Books. ISBN 0871567784

- Mulvaney, K. (2003). The Whaling Season: An Inside Account of the Struggle to Stop Commercial Whaling. Washington D.C.: Island Press. ISBN 1559639784

- Haug, T., Lindstrøm, U., Nilssen, K.T., Røttingen, I. And Skaug, H.J. (1996) Diet and food availability for Northeast Atlantic minke whales, Balaenoptera acutorostrata. Rep. Int. Whal. Commn.

- Folkow, L. P., Haug, T., Nilsen, K. T., Nordøy, E. S. (1997) Estimated prey consumption of minke whales Balaenoptera acutorostrata in Northeast Atlantic waters in 1992-1995. Document ICES CM 1997/GG:01.

- Schweder, T., Hagen, G. S. and Hatlebakk, E. (2000) Direct and indirect effects of minke whale abundance on cod and herring fisheries: A scenario experiment for the Greater Barents Sea. NAMMCO Scientific publications

Websites

- High North Alliance pro-whaling group homepage

- WhaleWatch anti-whaling group homepage

- Greenpeace - anti-whaling site

- Seashepherd - anti-whaling site

- C. George Muller (Marine Mammal Biologist and Author) - anti-whaling site

- "For watching or eating, Neither side gives ground in the battle over commercial whaling", The Economist July 26 2001.

- High North Alliance - Pro whaling site

- List of research papers submitted by Japan´s ICR to the scientific committee of the IWC

- World Council of Whalers - Pro Whaling NGO

- " A bloody war - Obduracy in the face of hypocrisy" The Economist Dec 30th 2003

- Australian Whaling History

- Korean Pirate Whaling Expose

- Where Does Japan's Whale Meat Come From. International Fund for Animal Welfare, 22 April 1994.

- Sigurjonsson, J. and G. A. Vikingsson (1997). Seasonal Abundance of and Estimated Food Consumption by Cetaceans in Icelandic and Adjacent Waters. J. Northw. Atl. Fish.Sci. Vol. 22:271-287

News articles

- "Whales 'absolved' on fish stocks". BBC News. 19 July 2004. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Report on Pauly's finding - "Iceland divided over whaling". BBC News. 15 August 2003. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Whaling 'too cruel to continue'". BBC News. 9 March 2004. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - report on the Whalewatch claims that the method of killing is inhumane

External links

- Online Documentary about the whale hunters of Lamalera

- Christmas 2005: Greenpeace confronts Japanese whalers in the Southern Ocean

- Christmas 2005: Open Letter to Greenpeace Japan from The Japanese Institute of Cetacean Research ( PDF )

- Greenpeace page about whaling

- IFAW's Stop Whaling Now Campaign

- High North Alliance - pro-whaling web page

- Vancouver Review - Terry Glavin Harpoons some Greenpeace pieties.

- World Conservation Trust Foundation on whaling

- Press release from IWMC on whaling

- Comment from IWC: Iceland and Commercial whaling