Shanku

| Shanku | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Shanku worn by a civil official, Western Jin | |||||||||||||||||||

Illustration of a woman wearing shanku from 1800s. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 衫褲 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 衫裤 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Shirt and trousers | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| English name | |||||||||||||||||||

| English | Samfoo (British English) / Samfu / Aoku | ||||||||||||||||||

Shanku (simplified Chinese: 衫裤; traditional Chinese: 衫褲), also known as samfu (or samfoo) in English[1] and in Cantonese spelling[2] and sometimes referred as aoku (simplified Chinese: 袄裤; traditional Chinese: 襖褲; pinyin: ǎokù; lit. 'coat trousers'),[3]: 87 [4] ruku (simplified Chinese: 襦裤; traditional Chinese: 襦褲; pinyin: rúkù; lit. 'jacket trousers'),[5]: 23–26 is a generic term which refers to a two-piece set of Chinese attire; it is composed of a Chinese upper garment which typically closes on the right called shan (Chinese: 衫), ru (Chinese: 襦; pinyin: rú) or ao (simplified Chinese: 袄; traditional Chinese: 襖), and a pair of long trousers ku (simplified Chinese: 裤; traditional Chinese: 褲).[2][6] Other terms such as duanda (Chinese: 短打), duanhe (Chinese: 短褐; lit. 'short brown') or shuhe (Chinese: 竖褐; lit. 'vertical brown') refers to the set of upper garment (which is generally above and below the hips and knees) and trousers made of coarse cloth which was generally worn for manual labour (e.g. farm work) and by martial artists.[7] The generic term kuxi/kuzhe (Chinese: 袴褶) is typically used to refer to military or riding style attire which is composed of a jacket and trousers.[8]: 319 [9][3]: 45 Although the kuxi/kuzhe were often times associated with Hufu, some of these garment items and styles were in fact Chinese innovations.[8]: 319 As a form of daily attire, the shanku was mainly worn by people from lower social status (e.g. labourers)[10][3]: 1 and by shopkeepers or retainers from wealthy household[3]: xviii in China. The shanku was originally worn by both genders.[6] Up until the mid-20th century, it was popular in China and outside of China where it was worn by overseas Chinese in countries, such as Singapore,[2] Malaysia,[10] Suriname,[11] etc. It is still worn in present-day China and can be found in rural areas.[6][2]

Terminology

In English language, shanku is commonly written as 'samfoo' in British English or 'samfu'.

According to the Collins English Dictionary, the samfoo/samfu (pronounced: /ˈsæmfu/) originated from the combination of the Chinese (Cantonese) words "sam" (dress) and "foo" (trousers).[1]

The Oxford Learner's Advanced Dictionaries and the Concise Oxford English Dictionary indicate that the term samfu originated in the 1950s from the Cantonese dialect 'shaam foò', 'shaam' which means ‘coat’ and 'foò' which means ‘trousers’.[12][13]: 1272

Among English dictionaries, there are variation in the definition of samfoo/ samfu:

- The Collins English Dictionary defines samfoo/ samfu as being "a style of casual dress worn by Chinese women, consisting of a waisted blouse and trousers".[1]

- The Oxford Learner's Advanced Dictionaries defines samfu as being "a light suit consisting of a jacket with a high collar and loose trousers, traditional in China".[12]

- The 12th edition of the Concise Oxford English Dictionary defines samfu as "a suit consisting of high-necked jacket and loose trousers, worn by Chinese women".[13]: 1272

Design and Construction

The shanku is a two-piece set of attire, which is composed of a jacket as an upper garment and a pair of trousers lower garment. More precisely, the shanku is composed of the shan and the trousers generally known as ku.

The shan and the ku were typically made of similar fabrics.[6] However, the two garments were sometimes made separately and did not belong to the same set of clothing.[6]

Upper garment

The shan (衫) or ao (袄; 襖) or ru (襦)[3]: 50 all refer to Chinese upper garment, which typically has a side fastening to the right.[14][6]

- Prior to the Qing dynasty, the upper garment were jiaoling youren, cross-collared which closed to the right, as the ones worn in Ming dynasty and the previous dynasties instead of the curved/slanted opening which was commonly worn in the late Qing.[15]

- The shan could have a mandarin collar,[14]

- The shan could be long-sleeved, short-sleeved,[16] or sleeveless[14] depending on the time period. The sleeves could be wide or narrow depending on styles and time period.[15]

- The shan varied in length depending on the time period - it could be thigh-length.[6]

-

Illustration of shan (衫) from the Chinese encyclopedia Gujin Tushu Jicheng, between 1700 and 1725 AD.

-

Han woman's jacket (袄) with slanted opening and high collar, 19th century.

Lower garment

The ku (裤; 褲), as a general term, was a pair of long trousers which could be loose or narrow.[6] There are many types of ku with some having rises while others did not.[17] Trousers with rises were typically referred as kun to differentiate from the ku which typically referred to trousers without rises.

Fitting

The shanku is traditionally loose in terms of fitting.[16] However, due to the influence of Western fashion, it became more tight fitting in the 1950s and 1960s.[16]

Colours

The shanku was typically dyed in black, blue or grey.[6] The waistband of the ku was typically made of lighter coloured fabric, such as blue or white.[6] However, the colours of the shanku could vary depending on ethnic groups.[6]

History and development

Pre-history

In the Neolithic period, the trousers were known as jingyi (Chinese: 胫衣) and was the original form of the trousers called ku (裤).[17] The form of the Neolithic jingyi was different from the trousers worn nowadays. The jingyi came in pairs like shoes.[17] They were knee-high trousers which were tied on the calves and only covered the knees and the ankles; thus allowing its wearer's thighs to be exposed; due to this reason, ancient Chinese wore yishang on top of their jingyi to cover their lower body.[17] The jingyi continued to be worn until the early Han dynasty.[17]

Shang dynasty

Hanfu dates at least back to the Shang dynasty.[18]: 121 Prior to the introduction of foreign clothing during the Warring States period, ruku (襦裤; lit 'jacket trousers') was worn, and a lower garment called chang (裳) had to cover the trousers.[note 1][5]: 23–26 In Shang dynasty, the slaveholders wore upper garments which closed to the right side (youren) with trousers or skirts.[19]: 15 The trousers in this period were split-crotch and had to be worn to be worn with a knee-length tunic.[18]: 121

Zhou dynasty, Spring and Autumn period, and Warring States period

In the Zhouli, it is recorded that exorcists wore black trousers and red jackets.[20]

Influence of Hufu

During the Warring States period, King Wuling of Zhao (r. 326–298 BC) instituted hufuqishe (Chinese: 胡服騎射; lit. 'Hu clothing and mounted archery') policies which involved the adoption of hufu to facilitate horse riding.[21][22] King Wuling was also known for wearing foreigner style long trousers and upper garments wth narrow sleeves.[23]

The nomadic clothes adopted by King Wuling consisted of belts, short upper garment and trousers.[19]: 16 The hufu introduced by King Wuling was designated as shangyi xiaku (Chinese: 上褶下袴; lit. 'short coat on upper body', 'trousers on lower body').[5]: 23–26 However, the trousers, which was introduced in Central China by King Wuling of Zhao, had loose rise, and it was referred as kun (Chinese: 裈) instead of ku (裤).[17] The short garment was a coat was called xi (褶; lit. 'coat'), which appears to have been the outermost coat of all garment, resembling a robe with short body and loose sleeves.[5]: 23–26 The term daxi (大褶, lit 'big coat') also exist, but they are only long enough to cover the knees, which suggest that the other forms of xi were shorter than knee-length.[5]: 23–26

Under the influence of the kun, the jingyi evolved until the thighs were lengthened to cover the thighs forming the ku (裤) and a waist enclosure was added; however, the ku had an open rise and rear which would allowed for excretion purposes.[17] Since the ku had an open rise and rear, the yishang continued to be worn on top of the ku.[17] Compared to the nomadic kun, the ku was well-accepted by the Chinese as it was more aligned with the Han Chinese tradition.[17] The trousers with loose rise, kun (Chinese: 裈), which was adopted from the clothing of northern nomadic people was mainly worn by the military troops and servants while the general population typically continued to wear jingyi (Chinese: 胫衣).[17] The nomadic-style kun never replaced the ku and was only worn by military and by the lower class.[17]

The nomadic-style loose rise trousers (i.e. kun) later influenced the formation of other forms of trousers such as dashao (i.e. trousers with extremely wide legs) which appeared in the Han dynasty and dakouku (i.e. trousers with tied strings under the knees).[17] These forms of trousers were Chinese innovations.[17]

Qin dynasty

In Qin dynasty, short clothing became more common and trousers were generally worn from what can be observed from the unearthed Qin dynasty tomb figures.[23] Trousers (ku 袴) was worn with jackets ru (Chinese: 襦), also known as shangru (Chinese: 上襦) along with daru (Chinese: 大襦; outerwear).[24] The trousers were often wide at the top and narrower at the bottom and could be find with rise.[24] Terracotta warriors, for example, wears a long robe which is worn on top of skirt and trousers.[25] The Qin artisans valued contrasting colours; for example, upper garments which were green in colour were often decorated with red or purple border; this upper garment would often be worn together with blue, or purple, or red trousers.[26]

Han dynasty

A long robe called shenyi was worn since the Spring and Autumn periods.[17] Since the Han dynasty, trousers with rise became more common.[27]

Starting since the Eastern Han dynasty, trousers with rise gradually started to be worn, the zhijupao of the Han dynasty gradually replaced the qujupao.[28][29]: 43 While shenyi was mainly worn for formal occasions in the Han dynasty, men wore a waist-length ru (襦) and trousers in their ordinary days while women wore ruqun.[note 2][19]: 16

Manual labourers tended to be wear even shorter upper garment and lower garment as due to their convenient use for work.[23]

The trousers dashao, dakouku and qiongku were worn in the Han dynasty.[17] The dashao was worn with a loose robe (either shenyi or paofu) in the Han dynasty by both military and civil officials.[17] The dakouku had a closed rise.[17] The qiongku is a type of ku which covered the hips and legs and its rise and hips regions were closed at the front and multiple strings were used to tie it at the back of its wearer; it was made for palace maids.[17] The qiongku continued to be worn for a long period of time, and was even worn in the Ming dynasty.[17]

Wei, Jin, Northern, and Southern dynasties

In the early medieval period of China (220-589 AD), male and female commoners commoners (e.g. servants and field labourers) wore a full-sleeved, long jacket (either waist or knee length) with cross-collar closing to the right with was tied with a belt.[30] Common women could either wear skirts or trousers under their jackets.[30] Full trousers with slightly tempered cuffs or trousers which were tied just below the knees were worn under the jacket.[30] In tombs inventories dating to the early 600s, cases of shanku (衫袴), xiku (褶袴), and kunshan (裈衫) can be found.[8]: 325

The trousers bounded at knees allowed for greater ease of movement.[30] The trousers with cords below the knees appeared in Western Jin to increase ease of movements when horseback riding or when on military duty.[8]: 319 This style of ku was however not a stylistic invention from the Northern people and were not a form of nomad clothing.[8]: 319

Kuzhe (袴褶), sometimes referred as kuxi (袴褶) which is literally translated as "jacket and trousers",[8]: 319 is a set of attire which consisted of the dakouku and tight-fitting upper garment which reached the knee.[17] It was a popular form of clothing and was worn by both genders, and it was worn in by both military and civil officials in the Northern and Southern dynasties.[17] A form of xi was in the form of a yuanlingshan with tight sleeves, the xi was slightly longer than the waist-length ru; this form of xi originated from the Northern minorities.[19]: 16 The kuzhe (袴褶) which appeared in the late Northern dynasty, was created by assimilating non-Han cultures in order to create a new design which reflected the Han Chinese culture.[17] During this period, the nomadic tribes, which also wore their own styles of kuzhe, ended up being influenced by the Han Chinese style due to the multiculturalism aspect of this period.[17]

In the Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern dynasties, the dakouku, especially the ones with a wide bottom, became popular among aristocrats and commoners alike.[17] The dakouku in this period also had closed-rise.[17]

-

Shanku (left) and ruqun (middle and right), Three Kingdoms period.

-

Male commoner wearing a long knee-length jacket and trousers, Western Jin Dynasty (265–316 CE)

-

Xianbei female warrior wearing trousers and upper garment.

-

Civil official in shanku, Western Wei

-

Tomb Brick of Wei, Jin, or Southern-Northern Dynasties

-

Men wearing shanku. Painting from Yanju's tomb, also known as Jiuquan Dingjia Gate No. 5 Tomb, 5th century AD.

Sui to Tang dynasties

From the Sui to the Tang dynasties, the kuzhe became popular.[17]

In Tang dynasty, the trousers which were worn by men were mainly worn with a robe (i.e. paofu).[17]

-

Sui dynasty attendant.

Song to Yuan dynasty

In Song dynasty, labourers who performed heavy tasks preferred to wear short jackets and trousers due to its convenience.[31]: 53 A new type of ku, known as xiku (i.e., knee-length trousers, also known as kuwa) became popular in the Song and Yuan dynasties but was sometimes banned by the emperors.[17] Narrow trousers, known as xiaoku, was also worn by the general population during this period.[17] In Yuan dynasty, some scholars and commoners wore Mongol-style kuzhe (i.e. the Mongol terlig) which was braided at the waists and had pleats and narrow-fitting sleeves.[9]

-

A woman (in the middle) wearing a shanku with an apron; a Song dynasty painting.

-

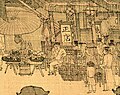

Peasant men wearing shanku, Song dynasty painting.

-

Seller wearing shanku.

-

A man wearing shanku vs men wearing paofu.

Ming dynasty

In Ming dynasty, the trousers with open-rise and close-rise were worn by men and women.[17] Women in Ming continued to wear trousers under their skirts.[17]

In the late Ming dynasty, jackets with high collars started to appear.[3]: 93–94 The standup collar were closed with interlocking buttons made of gold and silver,[32] called zimukou (Chinese: 子母扣).[33] The appearance of interlocking buckle promoted the emergence and the popularity of the standup collar and the Chinese jacket with buttons at the front, and laid the foundation of the use of Chinese knot buckles.[32] In women garments of the Ming dynasty, the standup collar with gold and silver interlocking buckles became one of the most distinctive and popular form of clothing structure; it became commonly used in women's clothing reflecting the conservative concept of Ming women's chastity by keeping their bodies covered and due to the climate changes during the Ming dynasty (i.e. the average temperature was low in China).[32]

-

Ming dynasty portrait of a person wearing white trousers and blue top.

-

Fisherman, Ming dynasty painting.

Qing dynasty - 19th Century

The high collar jacket continued to be worn in Qing dynasty, but it was not a common feature until the 20th century.[3]: 93–94 In the late Qing, the high collar become more popular and was integrated to the jacket and robe of the Chinese and the Manchu becoming a regular garment feature instead of an occasional feature. For the Han Chinese women, the stand-up collar became a defining feature of their long jacket; this long jacket with high collar could be worn over their trousers but also over their skirts (i.e. aoqun). The high collar remained a defining feature of their jacket even in the first few years of the republic.[3]: 93–94

In Qing dynasty, Han Chinese women who wore shanku without wearing a skirt on top of their trousers were typically people born from the lower social class.[31]: 82 Otherwise, they would wear trousers under their skirts which is in accordance with the traditions since the Han dynasty.[17] In Mesny's Chinese Miscellany written in 1897 by William Mesny, it was however observed that skirts were worn by Chinese women over their trousers in some regions of China, but that in most areas, skirts were only used when women would go out for paying visits.[34]: 371 He also observed that the wearing of trousers was a national custom for Chinese women and that trousers were worn in their homes when they would do house chores; he observed that women were dressed almost like men when working at home, except that their trousers had trims at the bottom of different coloured materials.[34]: 371

In the 19th century, the shan was long in length and the trousers ku was wide.[6] In the late 19th century, men stopped wearing the shan which closes to the right and started wearing a jacket with a central-opening which looks similar to the Tangzhuang.[6]

-

Qing dynasty men wearing shanku, before 1912 AD.

-

A woman wearing a white shan/ao and dark coloured ku.

-

Woman wearing a blue ao/shan and pink trousers.

-

A lady's maid.

-

Child's shanku.

-

shanku outfit, late 19th century

20th Century

In the 20th century, the 19th century long shan gradually became shorter and become more fitted.[6] The neckband of the shan was also narrow.[6] Sleeveless and short-sleeved shanku also existed in the 20th century.[14][16]

In the 1950s, women of the lower status and those worked on farms would sometimes wear shanku which was decorated with floral patterns and checks.[6] People living in urban areas started to wear western clothing while people in rural areas continued to wear shanku.[6] In Hong Kong, shanku continued to be worn when people were away from their workplace.[6]

-

Hakka woman wearing shanku, between 1935 and 1945

-

Hakka woman in shanku, 1950.

During the Great Leap Forward, the Mao suit became popular. but it was not expected for children to wear the Mao suit.[6] While in cities, children started to wear Western style clothing, the children in the rural areas continued to wear the traditional shanku which were made of cotton checked fabrics, stripe fabrics, or other patterned fabrics.[6]

Ethnic clothing

Han Chinese

Both Han Chinese women and men of the labouring classes wore shanku.[3]: 1 The trousers, which could be found either narrow or wide, were a form of standard clothing for the Han Chinese.[3]: 1

Hakka

The Hakka people wears shanku as their traditional clothing;[35] both Hakka men and women wear it.[36] The preferred colours of the Hakka shanku is typically blue and black.[36]

Hoklo

The Hoklo people wears shanku which is composed of fitted-style of shan which has a deeply curved hem and black-coloured trousers ku.[6] Their shan was characterized by the bands decoration at the sleeves edges and at the garment opening as well as the collar of the shan which was very narrow and also consisted of piping rows.[6] They typically wore bright colours such as light blue as every day wear while colours such as purple, deep blue, deep turquoise were reserved for special occasions.[6]

Tanka

The Tanka people also wear shanku which is distinctive in style wherein the shan and the ku matched in colour; they prefer wearing colours which are lighter and brighter, such as pale green, pale blue, turquoise, yellow and pink.[6] These lighter colours tended to be preferred by younger women or by newly married women; they were also worn on special occasions.[6] On the other hand, darker colours were favoured by older women.[6]

Influences and derivatives

Vietnam

In the 15th century (from 1407 to 1478), the Vietnamese women adopted Chinese trousers under the occupation of the Ming dynasty.[37][38] During the 17th and 18th century, Vietnam was divided in two regions with the Nguyen lords ruling the South. The Nguyen lords ordered that southern men and women had to wear Chinese-stye trousers and long front-buttoning tunics to differentiate themselves from the people living in the North. This form of outfit developed with time over the next century becoming the precursor of the áo dài, the outfit generally consisted of trousers, loose-fitting shirt with a stand-up collar and a diagonal right side closure which run from the neck to the armpit; these features were inspired by the Chinese and the Manchu clothing.[37]

In the pre-20th century, Vietnamese people of both sexes continue to maintain old Ming-style of Chinese clothing consisting of a long and loose knee-length tunics and ankle-length, loose trousers.[39] In the 1920s, the form ensemble outfit was refitted to become the Vietnamese dress female national dress, the ladies' áo dài.[39]

Related content

- Áo dài - a Vietnamese equivalent

- Ru - a type of Chinese upper garment

- Hufu - non-Han Chinese clothing

See also

Notes

- ^ The term chang in a broad sense can refer to any to lower garments, including trousers and skirts. When chang is used over trousers, it typically refers to a skirt; upper garment with chang (skirt) form a set of attire called yishang. See page ruqun for more details.

- ^ Authors Feng and Du (2015) specifies that the jacket worn is ru, which is cut to the waist, in this context. They however do not elaborate on the precise type of trousers.

References

- ^ a b c "Definition of 'samfoo'". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins Publishers. 2022.

- ^ a b c d Ho, Stephanie (2013). "Samfu | Infopedia". eresources.nlb.gov.sg. Archived from the original on 2022-03-27. Retrieved 2021-05-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Finnane, Antonia (2008). Changing clothes in China : fashion, history, nation. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14350-9. OCLC 84903948.

- ^ "Evolution and revolution: Chinese dress 1700s-1990s - Glossary". archive.maas.museum. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ a b c d e Rui, Chuanming (2021). On the ancient history of the Silk Road. Singapore. ISBN 978-981-12-3296-1. OCLC 1225977015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Garrett, Valery (2012). Chinese Dress : From the Qing Dynasty to the Present. New York: Tuttle Pub. ISBN 978-1-4629-0694-9. OCLC 794664023.

- ^ "What did Ancient Chinese Peasants Wear? - 2021". www.newhanfu.com. 2020-04-27. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f Dien, Albert E. (2007). Six dynasties civilization. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07404-8. OCLC 72868060.

- ^ a b Chen, BuYun (2019), Riello, Giorgio; Rublack, Ulinka (eds.), "Wearing the Hat of Loyalty: Imperial Power and Dress Reform in Ming Dynasty China", The Right to Dress: Sumptuary Laws in a Global Perspective, c.1200–1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 416–434, doi:10.1017/9781108567541.017, ISBN 978-1-108-47591-4, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ a b Koh, Jaime (2009). Culture and customs of Singapore and Malaysia. Lee-Ling Ho. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-313-35115-0. OCLC 318420874.

- ^ Tjon Sie Fat, Paul Brendan (2009). Chinese new migrants in Suriname : the inevitability of ethnic performing. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-90-485-1147-1. OCLC 647870387.

- ^ a b "Definition of samfu noun from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary". Oxford Learner's Dictionaries. 2022.

- ^ a b Concise Oxford English dictionary. Angus Stevenson, Maurice Waite (12th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-19-960108-0. OCLC 692291307.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d "Sleeveless 'samfoo' with a floral motif". www.roots.gov.sg. 2021. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ a b Jiang, Wanyi; Li, Zhaoqing (2021-01-06). "Analysis on Evolution, Design and Application of Women's Traditional Coats in Beijing in the Late Qing Dynasty and the Early Republic of China". Atlantis Press: 641–648. doi:10.2991/assehr.k.210106.123. ISBN 978-94-6239-314-1.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d "Traditional Chinese 'samfoo'". www.roots.gov.sg. 2021. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Xu, Rui; Sparks, Diane (2011). "Symbolism and Evolution of Ku-form in Chinese Costume". Research Journal of Textile and Apparel. 15 (1): 11–21. doi:10.1108/rjta-15-01-2011-b002. ISSN 1560-6074.

- ^ a b Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2015). World Clothing and Fashion : an Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Social Influence. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-45167-9. OCLC 910448387.

- ^ a b c d Feng, Ge (2015). Traditional Chinese rites and rituals. Zhengming Du. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 1-4438-8783-8. OCLC 935642485.

- ^ Lorge, Peter (2017). Warfare in China to 1600. USA: New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-87379-6. OCLC 999622852.

- ^ Between history and philosophy : anecdotes in early China. Paul van Els, Sarah A. Queen. Albany. 2017. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-1-4384-6613-2. OCLC 967791392.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Zhao, Yin (2014). Snapshots of Chinese culture. Xinzhi Cai. Los Angeles. ISBN 978-1-62643-003-7. OCLC 912499249.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Xu, Zhuoyun (2012). China : a new cultural history. Timothy Danforth Baker, Michael S. Duke. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-231-15920-3. OCLC 730906510.

- ^ a b Hao, Peng; Ling, Zhang (2018). "On "Skirts" and "Trousers" in the Qin Dynasty Manuscript Making Clothes in thh Collection of Peking University". Chinese Cultural Relics. 5 (1): 248–268. doi:10.21557/CCR.54663802. ISSN 2330-5169 – via East View.

- ^ "A study on skirt construction in qin dynasty" (PDF). 18th Annual IFFTI Conference. Yuanfeng Liu, Frances Corner; China Textile & Apparel Press (Editors). The International Foundation of Fashion Technology Institutes: 199–205. 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Miller, Allison R. (2021). Kingly splendor : court art and materiality in Han China. New York. ISBN 0-231-55174-6. OCLC 1152416590.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hua, Mei (2011). Chinese clothing (Updated ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. p. 14. ISBN 0-521-18689-7. OCLC 781020660.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Zang, Yingchun; 臧迎春. (2003). Zhongguo chuan tong fu shi. 李竹润., 王德华., 顾映晨. (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Wu zhou chuan bo chu ban she. p. 32. ISBN 7-5085-0279-5. OCLC 55895164.

- ^ 5000 years of Chinese costumes. Xun Zhou, Chunming Gao, 周汛, Shanghai Shi xi qu xue xiao. Zhongguo fu zhuang shi yan jiu zu. San Francisco, CA: China Books & Periodicals. 1987. ISBN 0-8351-1822-3. OCLC 19814728.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d Early medieval China : a sourcebook. Wendy Swartz, Robert Ford Campany, Yang Lu, Jessey Jiun-Chyi Choo. New York. 2014. p. 435. ISBN 0-231-53100-1. OCLC 873986732.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Hua, Mei; 华梅 (2004). Zhongguo fu shi (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Wu zhou chuan bo chu ban she. ISBN 7-5085-0540-9. OCLC 60568032.

- ^ a b c Hao, Xiao’ang; Yin, Zhihong (2020). "Research on Design Aesthetics and Cultural Connotation of Gold and Silver Interlocking Buckle in the Ming Dynasty". Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2020). Paris, France: Atlantis Press. doi:10.2991/assehr.k.200907.030.

- ^ "Zimu Kou - Exquisite Ming Style Hanfu Button - 2021". www.newhanfu.com. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ^ a b Mesny, William (1897). Mesny's Chinese Miscellany. China Gazette Office. OCLC 810192986.

- ^ República of China (2010). Taiwan yearbook 2010. Taiwan: Govermment Information Office. p. 237. ISBN 978-986-02-5278-1. OCLC 706219891.

- ^ a b "Hakka Clothing". club.ntu.edu.tw. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ a b Steele, Valerie (2005). Encyclopedia of clothing and fashion. Farmington Hills, MI: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 61. ISBN 0-684-31394-4. OCLC 55085919.

- ^ Encyclopedia of national dress : traditional clothing around the world. Jill Condra. Santa Barbara, Calif. 2013. p. 760. ISBN 978-0-313-37637-5. OCLC 843418851.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Reid, Anthony (2015). A history of Southeast Asia : critical crossroads. Chichester, West Sussex. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-118-51295-1. OCLC 893202848.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)