Tony Hsieh

Tony Hsieh | |

|---|---|

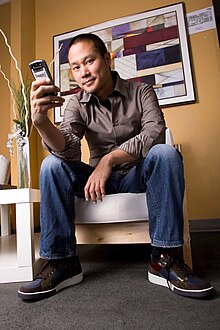

Hsieh in 2009 | |

| Born | December 12, 1973 Urbana, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | November 27, 2020 (aged 46) Bridgeport, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Education | Harvard University (AB) |

| Occupation | Businessman |

| Years active | 1995–2020 |

| Known for | CEO of Zappos (1999–2020) |

Anthony Hsieh (/ʃeɪ/ SHAY;[2] December 12, 1973 – November 27, 2020)[3][4][5] was an American internet entrepreneur and venture capitalist. He retired as the CEO of the online shoe and clothing company Zappos in August 2020 after 21 years.[6] Prior to joining Zappos, Hsieh co-founded the Internet advertising network LinkExchange, which he sold to Microsoft in 1998 for $265 million.[7]

Early life and education

Hsieh was born in Urbana, Illinois, to Richard and Judy Hsieh, immigrants from Taiwan who met in graduate school at the University of Illinois. Hsieh's family moved to Lucas Valley area of Marin County, California when he was five. His mother was a social worker, and his father a chemical engineer at Chevron Corp.[8][2] He had two younger brothers, Andy and Dave. Hsieh attended the Branson School.[9]

In 1995, Hsieh graduated from Harvard University with a degree in computer science.[10] While at Harvard, he managed the Quincy House Grille selling pizza to the students in his dorm; his best customer, Alfred Lin, would later become Zappos's chief financial officer and chief operating officer.[11] After college, Hsieh worked for Oracle Corporation.[12] After five months, he left to co-found the LinkExchange advertising network.[13]

Career

LinkExchange

In 1996, Hsieh started developing the idea for an advertising network called LinkExchange with his college classmates Sanjay Mandan and Ali Partovi.[14] Members were allowed to advertise their site over LinkExchange's network by displaying banner ads on its website. They launched in March 1996, with Hsieh as CEO, and found their first 30 clients by direct emailing webmasters.[15] The site grew, and within 90 days LinkExchange had over 20,000 participating web pages and had its banner ads displayed over 10 million times.[16] By 1998, the site had over 400,000 members and 5 million ads rotated daily.[17] In November 1998, LinkExchange was sold to Microsoft for $265 million.[18][19]

Venture Frogs

After LinkExchange sold to Microsoft, Hsieh co-founded and owned Venture Frogs, an incubator and investment firm, with his business partner, Alfred Lin.[20][21] The name originated from a dare. One of Hsieh's friends said she would invest everything if they chose "Venture Frogs" as the name, and the pair took her up on the bet, although they had not seen any money as of 2011.[22] They invested in a variety of tech and Internet startups, including Ask Jeeves, OpenTable and Zappos.[22]

Zappos

In 1999, Nick Swinmurn approached Hsieh and Lin with the idea of selling shoes online.[11] Hsieh was initially skeptical and almost deleted Swinmurn's initial voice mail. After Swinmurn mentioned that "footwear in the US is a $40 billion market, and 5% of that was already being sold by paper mail order catalogs," Hsieh and Lin decided to invest through Venture Frogs. Two months later, Hsieh joined Zappos as the CEO, starting with $1.6 million of total sales in 2000.[11] By 2009, revenues reached $1 billion.[23][24]

Without a precedent to guide him, Hsieh learned how to make customers feel comfortable shopping for shoes online. Zappos offered free shipping and free returns, sometimes of several pairs. Hsieh rethought Zappos structure, and in 2013 it became for a time a holacracy without job titles, reflecting his belief in employees and their ability to self-organize.[25] The company hired only about 1% of all applicants.[26] Named for the Spanish word for shoes, "zapatos", Zappos was often listed in Fortune as one of the best companies to work for, and beyond high salaries and being an inviting place to work it delivered extraordinary customer service.[27]

Hsieh loved the game of poker and moved Zappos headquarters to Henderson, Nevada, and eventually to downtown Las Vegas.[27]

On July 22, 2009, Amazon announced the acquisition of Zappos.com in a deal valued at approximately $1.2 billion.[28] Hsieh is said to have made at least $214 million from the sale, not including money made through his former investment firm Venture Frogs.[29][30]

On August 24, 2020, Hsieh retired as the CEO of Zappos after 21 years at the helm.[6]

JetSuite

Hsieh joined JetSuite's board in 2011. He led a $7 million round of investment in the growing private "very light jet" field with that company. The investment allowed JetSuite to add two new Embraer Phenom 100 jets which have two pilots, two engines and safety features equivalent to large commercial passenger jets but weigh less than 10,000 pounds (4,500 kg) and are consequently highly fuel-efficient.[31]

Real estate rejuvenation projects

Downtown Project – Las Vegas

From 2009 until his death, Hsieh, who was still running the downtown Las Vegas-based Zappos.com business, organized a major re-development and revitalization project for downtown Las Vegas, which had been for the most part left behind compared to the Las Vegas Strip's growth. Hsieh originally planned the Downtown Project as a place where Zappos.com employees could live and work, but the project grew beyond that to a vision where thousands of local tech and other entrepreneurs could live and work.[32][33] Projects funded include The Writer's Block, the first independent bookseller in Las Vegas.[34]

Park City, Utah

After stepping down as CEO of Zappos in August 2020, Hsieh bought multiple properties in Park City, Utah, with a total market value around $56 million.[35]

Awards

Hsieh was a member of the Harvard University team that won the 1993 ACM International Collegiate Programming Contest in Indianapolis, ranking first of 31 entrants.[36]

Hsieh received an Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year award for the Northern California region in 2007.[37]

Delivering Happiness

Hsieh's 2010 book Delivering Happiness focused on his entrepreneurial endeavors. It was profiled in many world publications, including The Washington Post, CNBC, TechCrunch, The Huffington Post and The Wall Street Journal.[38][39][40][41][42] It debuted at No. 1 on the New York Times Best Seller List and stayed on the list for 27 consecutive weeks.[43][44]

Personal life

Hsieh resided primarily in Downtown Las Vegas, and also owned a residence in Southern Highlands, Nevada. Hsieh was known for taking extreme challenges regarding his body, including starving himself of oxygen to induce hypoxia, using nitrous oxide, and fasting to the point where he was under 100 pounds (45 kg).[45][46][47][48] Singer Jewel said that she was aware of Hsieh's extreme drug abuse and sent him a letter months before his death to warn him.[49]

Death

On the morning of November 18, 2020, Hsieh was injured in a house fire in New London, Connecticut, although his identity was not revealed at the time.[50] It has been reported that he was visiting family for Thanksgiving, and he either became trapped in a pool shed during the fire,[51] or barricaded himself inside and would not answer the door.[52][53][54] The exact cause of the fire is under investigation. He was rescued by firefighters and transported to the Connecticut Burn Center at Bridgeport Hospital to undergo treatment for burns and smoke inhalation, where he died on November 27, two weeks before his 47th birthday.[55][56] The Connecticut medical examiner determined that Hsieh died from smoke inhalation, and ruled his death was an accident.[52] News sources have suggested that his drug use and nitrous oxide use may have played a role in his death.[57][58]

The Wall Street Journal reported that according to property records, Hsieh was staying at a house that was possibly owned by a former Zappos employee, Rachael Brown.[59][60]

Further reading

Books

- Hsieh, Tony (2010). Delivering Happiness: A Path to Profits, Passion and Purpose. Grand Central Publishing. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-446-56304-8.[61]

- Grind, Kirsten (2022). Happy at Any Cost: The Revolutionary Vision and Fatal Quest of Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh. Simon and Schuster. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-982186-98-2.[62]

Articles

- Grind, Kirsten; Hagerty, James R.; Sayre, Katherine (December 6, 2020). "The Death of Zappos's Tony Hsieh: A Spiral of Alcohol, Drugs and Extreme Behavior". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

References

- ^ "10 Money Lessons from Billionaires". Ca.finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Rifkin, Glenn (November 28, 2020). "Tony Hsieh, Longtime Chief of Zappos, Dies at 46". The New York Times. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ Hsieh, Tony. Delivering Happiness.

The first official party of 810 would be on Saturday, December 11, 1999. At midnight, I would turn twenty-six.

- ^ Able, Kate. "Tony Hsieh, Zappos Luminary Who Revolutionized the Shoe Business, Dies at 46" Footwear News, November 27, 2020

- ^ Brindley, Emily. "Tony Hsieh, former CEO of Zappos, dies in Connecticut after New London house fire" Hartford Courant, November 28, 2020

- ^ a b Abel, Katie (August 24, 2020). "Exclusive: Visionary Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh Is Stepping Down After 21 Years". Footwear News. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ Cf. Delivering Happiness book by Hsieh. "In 1996, I co-founded LinkExchange, which was sold to Microsoft in 1998 for $265 million."

- ^ "Tony Hsieh, The Billion Dollar Interview", Entrepreneur Interviews

- ^ "Zappos founder Tony Hsieh enjoys the good life | The Seattle Times". April 17, 2011.

- ^ "Tony Hsieh". Seas.harvard.edu. March 22, 2013. Archived from the original on January 13, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c I Am CNBC Tony Hsieh Transcript Archived June 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine CNBC. August 15, 2007.

- ^ Wei, William Tony Hsieh: Here’s Why I Quit My Corporate Job At Oracle With No Real Plan (October 28, 2010), Business Insider.

- ^ Kim, Eugene (August 28, 2014). "23 Tech Rock Stars Who Went to Harvard". Business Insider. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ BEato, Greg. Scans: Barter for Banners. September 29, 1997.

- ^ Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh Talks Shoes on Bloomberg TV BNet. July 16, 2010.

- ^ Internet Link Exchange: 3rd month of operation celebrated. M2 Newswire via LexisNexis. June 17, 1996.

- ^ Frierman, Shelly. An Internet company with little freebies that could gain a place in the sun The New York Times. December 2, 1998.

- ^ Wei, William. Tony Hsieh: Here's Why I Quit My Corporate Job At Oracle With No Real Plan. Business Insider. October 28, 2010.

- ^ Tony Hsieh - Author Of “Delivering Happiness” And CEO Of Zappos Zappos.com.

- ^ Venture Frogs Launches New Incubator For Net Startups Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine URLwire. September 19, 1999.

- ^ Lee, Tom. Venture Frogs Internet Restaurant Logs on to the San Francisco Scene Archived March 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Asian Week. August 17, 2000.

- ^ a b Nelson, Erik. Venture Frogs in a Cyber-Marsh Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Profit Magazine. January 2000.

- ^ Hsieh, Tony. Why I Sold Zappos. Inc. Magazine. June 1, 2010.

- ^ Kee, Tameka. Amazon Buying Out Zappos.com For About $850 Million. Washington Post. July 23, 2009.

- ^ Recode (May 20, 2016). Tony Hsieh explains why he sold Zappos and what he thinks of Amazon. YouTube. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ Rifkin, Glenn (November 28, 2020). "Tony Hsieh, Longtime Chief of Zappos, Is Dead at 46". The New York Times. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Schudel, Matt (November 28, 2020). "Tony Hsieh, entrepreneur who made Zappos an online retail giant, dies at 46". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ Amazon Closes Zappos Deal, Ends Up Paying $1.2 Billion TechCrunch. November 2, 2009.

- ^ "What Everyone Made from the Zappos Sale". July 27, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ^ Jacobs, Alexandra (September 14, 2009). "Happy Feet". The New Yorker. pp. 66–71.

- ^ "Zappos shoe mogul invests in O.C. company". Ocregister.com. September 19, 2011. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ Pratt, Timothy (October 19, 2012). "What Happens in Brooklyn Moves to Vegas". The New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ "Downtown Project - Downtown Project Las Vegas". Downtownproject.com. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ Semuels, Alana (March 2, 2015). "Zappos' CEO Has Poured $350 Million into Revitalizing Downtown Vegas, Is It Enough?". Theatlantic.com. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ Barber, Megan (October 5, 2020). "Why is Ex-Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh Buying Houses En Masse in Utah?". Curbed. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ "ICPC World Champion Hall of Fame". Icpc.baylor.edu. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ "Ernst & Young Entrepreneur Of The Year Award, 2007". Archived from the original on September 2, 2011.

- ^ McDonough-Taub, Gloria Top Books: Delivering Happiness CNBC. August 19, 2010.

- ^ Spreading WOW The Washington Post August 27, 2010.

- ^ Delivering Happiness: A Movement TechCrunch. May 1, 2010.

- ^ ‘Delivering Happiness’: What Poker Taught Me About Business The Huffington Post. May 26, 2010.

- ^ Carrol, Paul Getting a Foothold Online The Wall Street Journal. June 7, 2010.

- ^ Hardcover Advice 06-27-2010 The New York Times.

- ^ Hardcover Advice 12-26-2010 The New York Times.

- ^ Sayre, Katherine; Hagerty, James; Grind, Kirsten (December 7, 2020). "The Death of Zappos's Tony Hsieh: A Spiral of Alcohol, Drugs and Extreme Behavior". Wall Street Journal – via www.wsj.com.

- ^ "At Zappos, Pushing Shoes and a Vision". Nytimes.com. July 17, 2015. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ "LIVING SMALL: AT DOWNTOWN'S AIRSTREAM PARK, HOME IS WHERE THE EXPERIMENT IS". Lasvegasweekly.com. February 5, 2015. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ Rich, Motoko (April 9, 2011). "Why Is the Head of Zappos Smiling?". The New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ Gifford, Storm. "Jewel wrote letter to Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh about supposed drug abuse months before his death: report". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ "One person rescued from New London house fire, taken to hospital". fox61.com. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ Streitfeld, David; Hussey, Kristin (January 26, 2021). "Tony Hsieh's Fatal Night: An Argument, Drugs, a Locked Door and Sudden Fire". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Grind, Kirsten (December 6, 2020). "The Death of Zappos's Tony Hsieh: A Spiral of Alcohol, Drugs and Extreme Behavior". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "Tony Hsieh, 'visionary' behind Zappos shoe retailer, dies aged 46". The Guardian. November 28, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ Perrett, Connor. "The fire that led to the death of former Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh occurred over a week before he succumbed to injuries". Insider. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ "Tony Hsieh dead at the age of 46 after being injured in house fire". Las Vegas Review-Journal. November 28, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ "Tony Hsieh, retired Zappos CEO, dies after New London house fire". Connecticut Post. November 28, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ Sayre, Kirsten Grind, James R. Hagerty and Katherine (December 7, 2020). "The Death of Zappos's Tony Hsieh: A Spiral of Alcohol, Drugs and Extreme Behavior". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Streitfeld, David; Hussey, Kristin (January 26, 2021). "Tony Hsieh's Last Night: An Argument, Drugs, a Locked Door and Sudden Fire". The New York Times.

- ^ "What we know about the fire that killed former Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh". Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ Hawkins, Lee (November 29, 2020). "Before Tony Hsieh's Death, Firefighters Rushed to Burning Home With Trapped Man". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ "Delivering Happiness: A Path to Profits, Passion and Purpose". Publisher's Weekly. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ "Happy at Any Cost: The Revolutionary Vision and Fatal Quest of Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh". Publisher's Weekly. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

External links

- 1973 births

- 2020 deaths

- 20th-century American businesspeople

- 21st-century American businesspeople

- Accidental deaths in Connecticut

- Amazon (company) people

- American businesspeople of Taiwanese descent

- American computer businesspeople

- American people of Chinese descent

- American people of Taiwanese descent

- American technology chief executives

- American technology company founders

- Businesspeople from Illinois

- Businesspeople from Nevada

- Businesspeople from the San Francisco Bay Area

- Businesspeople in online retailing

- Competitive programmers

- Deaths from fire in the United States

- Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences alumni

- People from the Las Vegas Valley

- Private equity and venture capital investors