Tautomer

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2015) |

Tautomers (/ˈtɔːtəmər/)[1] are structural isomers (constitutional isomers) of chemical compounds that readily interconvert.[2][3][4][5] The chemical reaction interconverting the two is called tautomerization. This conversion commonly results from the relocation of a hydrogen atom within the compound. The phenomenon of tautomerization is called tautomerism, also called desmotropism. Tautomerism is for example relevant to the behavior of amino acids and nucleic acids, two of the fundamental building blocks of life.

Care should be taken not to confuse tautomers with depictions of "contributing structures" in chemical resonance. Tautomers are distinct chemical species that can be distinguished by their differing atomic connectivities, molecular geometries, and physicochemical and spectroscopic properties,[6] whereas resonance forms are merely alternative Lewis structure (valence bond theory) depictions of a single chemical species, whose true structure is best described as the "average" of the idealized, hypothetical geometries implied by these resonance forms.

Examples

Tautomerization is pervasive in organic chemistry. It is typically associated with polar molecules and ions containing functional groups that are at least weakly acidic. Most common tautomers exist in pairs, which means that the hydrogen is located at one of two positions, and even more specifically the most common form involves a hydrogen changing places with a double bond: H−X−Y=Z ⇌ X=Y−Z−H. Common tautomeric pairs include:[7]

- ketone – enol: H−O−C=C ⇌ O=C−C−H, see keto–enol tautomerism

- enamine – imine: H−N−C=C ⇌ N=C−C−H

- cyanamide – carbodiimide

- guanidine – guanidine – guanidine: With a central carbon surrounded by three nitrogens, a guanidine group allows this transform in three possible orientations

- amide – imidic acid: H−N−C=O ⇌ N=C−O−H (e.g., the latter is encountered during nitrile hydrolysis reactions)

- lactam – lactim, a cyclic form of amide-imidic acid tautomerism in 2-pyridone and derived structures such as the nucleobases guanine, thymine, and cytosine

- imine – imine, e.g., during pyridoxal phosphate catalyzed enzymatic reactions

- R1R2C(=NCHR3R4) ⇌ (R1R2CHN=)CR3R4

- nitro – aci-nitro (nitronic acid): RR'HC–N+(=O)(O–) ⇌ RR'C=N+(O–)(OH)

- nitroso – oxime: H−C−N=O ⇌ C=N−O−H

- ketene – ynol, which involves a triple bond: H−C=C=O ⇌ C≡C−O−H

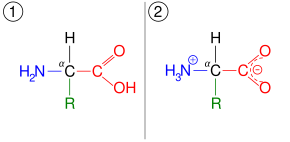

- amino acid – ammonium carboxylate, which applies to the building blocks of the proteins. This shifts the proton more than two atoms away, producing a zwitterion rather than shifting a double bond: H2N−CH2−COOH ⇌ H3N+

−CH2−CO−

2 - phosphite – phosphonate: P(OR)2(OH) ⇌ HP(OR)2(=O) between trivalent and pentavalent phosphorus.

Prototropy

Prototropy is the most common form of tautomerism and refers to the relocation of a hydrogen atom.[8] Prototropic tautomerism may be considered a subset of acid-base behavior. Prototropic tautomers are sets of isomeric protonation states with the same empirical formula and total charge. Tautomerizations are catalyzed by:[citation needed]

- bases, involving a series of steps: deprotonation, formation of a delocalized anion (e.g., an enolate), and protonation at a different position of the anion; and

- acids, involving a series of steps: protonation, formation of a delocalized cation, and deprotonation at a different position adjacent to the cation).

Two specific further subcategories of tautomerizations:

- Annular tautomerism is a type of prototropic tautomerism wherein a proton can occupy two or more positions of a heterocyclic system, for example, 1H- and 3H-imidazole; 1H-, 2H- and 4H- 1,2,4-triazole; 1H- and 2H- isoindole.[9][non-primary source needed][better source needed]

- Ring–chain tautomers occur when the movement of the proton is accompanied by a change from an open structure to a ring, such as the open chain and cyclic hemiacetal (typically pyranose or furanose forms) of many sugars.[7] (See Carbohydrate § Ring-straight chain isomerism.) The tautomeric shift can be described as H−O ⋅ C=O ⇌ O−C−O−H, where the "⋅" indicates the initial absence of a bond.

Valence tautomerism

Valence tautomerism is a type of tautomerism in which single and/or double bonds are rapidly formed and ruptured, without migration of atoms or groups.[10] It is distinct from prototropic tautomerism, and involves processes with rapid reorganisation of bonding electrons.

A pair of valence tautomers with formula C6H6O are benzene oxide and oxepin.[10][11]

Other examples of this type of tautomerism can be found in bullvalene, and in open and closed forms of certain heterocycles, such as organic azides and tetrazoles,[12] or mesoionic münchnone and acylamino ketene.

Valence tautomerism requires a change in molecular geometry and should not be confused with canonical resonance structures or mesomers.

Inorganic materials

In inorganic extended solids, valence tautomerism can manifest itself in the change of oxidation states its spatial distribution upon the change of macroscopic thermodynamic conditions. Such effects have been called charge ordering or valence mixing to describe the behavior in inorganic oxides.[13]

See also

References

- ^ "tautomer". Oxford Dictionaries - English. Archived from the original on 2018-02-19.

- ^ Antonov L (2013). Tautomerism: Methods and Theories (1st ed.). Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-33294-6.

- ^ Antonov L (2016). Tautomerism: Concepts and Applications in Science and Technology (1st ed.). Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-33995-2.

- ^ Smith MB, March J (2001). Advanced Organic Chemistry (5th ed.). New York: Wiley Interscience. pp. 1218–1223. ISBN 978-0-471-58589-3.

- ^ Katritzky AR, Elguero J, et al. (1976). The Tautomerism of heterocycles. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-020651-3.

- ^ Smith, Kyle T.; Young, Sherri C.; DeBlasio, James W.; Hamann, Christian S. (27 January 2016). "Measuring Structural and Electronic Effects on Keto–Enol Equilibrium in 1,3-Dicarbonyl Compounds". Journal of Chemical Education. 93 (4): 790–794. Bibcode:2016JChEd..93..790S. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00170.

- ^ a b Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Tautomerism". doi:10.1351/goldbook.T06252

- ^ Roman M. Balabin (2009). "Tautomeric equilibrium and hydrogen shifts in tetrazole and triazoles: Focal-point analysis and ab initio limit". J. Chem. Phys. 131 (15): 154307. Bibcode:2009JChPh.131o4307B. doi:10.1063/1.3249968. PMID 20568864.[non-primary source needed][better source needed]

- ^ a b IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "valence tautomerization". doi:10.1351/goldbook.V06591.html

- ^ E. Vogel and H. Günther (1967). "Benzene Oxide-Oxepin Valence Tautomerism". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 6 (5): 385–401. doi:10.1002/anie.196703851.

- ^ Lakshman Mahesh K., Singh Manish K., Parrish Damon, Balachandran Raghavan, Day Billy W. (2010). "Azide−Tetrazole Equilibrium of C-6 Azidopurine Nucleosides and Their Ligation Reactions with Alkynes". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 75 (8): 2461–2473. doi:10.1021/jo902342z. PMC 2877261. PMID 20297785.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Karen, Pavel; McArdle, Patrick; Takats, Josef (2014-06-18). "Toward a comprehensive definition of oxidation state (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 86 (6): 1017–1081. doi:10.1515/pac-2013-0505. ISSN 1365-3075. S2CID 95381734.

External links

Media related to Tautomerism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tautomerism at Wikimedia Commons