Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd/10th Earl of Devon

Hugh de Courtenay | |

|---|---|

| 2nd/10th Earl of Devon | |

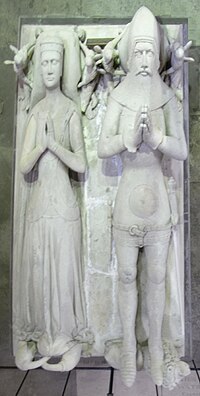

Effigy (restored) of Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd/10th Earl of Devon, south transept, Exeter Cathedral | |

| Born | 12 July 1303 |

| Died | 2 May 1377 (aged 73) |

| Noble family | Courtenay |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret de Bohun |

| Issue | Sir Hugh Courtenay, KG Thomas Courtenay Sir Edward Courtenay Robert Courtenay William Courtenay, Archbishop of Canterbury Sir Philip Courtenay Sir Peter Courtenay, KG Humphrey Courtenay Margaret Courtenay (the elder) Elizabeth Courtenay Katherine Courtenay Anne Courtenay Joan Courtenay Margaret Courtenay (the younger) ______ Courtenay (7th daughter) ______ Courtenay (8th daughter) ______ Courtenay (9th daughter) |

| Father | Hugh de Courtenay, 1st/9th Earl of Devon |

| Mother | Agnes de Saint John |

Sir Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd/10th Earl of Devon[1] (12 July 1303 – 2 May 1377),[2] 2nd Baron Courtenay, feudal baron of Okehampton[3] and feudal baron of Plympton,[4] played an important role in the Hundred Years War in the service of King Edward III. His chief seats were Tiverton Castle and Okehampton Castle in Devon. The ordinal number given to the early Courtenay Earls of Devon depends on whether the earldom is deemed a new creation by the letters patent granted 22 February 1334/5 or whether it is deemed a restitution of the old dignity of the de Redvers family. Authorities differ in their opinions,[5] and thus alternative ordinal numbers exist, given here.

Origins

Hugh de Courtenay was born on 12 July 1303, the second son of Hugh de Courtenay, 1st/9th Earl of Devon (1276–1340), by his wife Agnes de Saint John, a daughter of Sir John de Saint John of Basing, Hampshire. He succeeded to the earldom on the death of his father in 1340.[6] His elder brother, John de Courtenay (c.1296-11 July 1349), Abbot of Tavistock, as a cleric was unmarried and although he succeeded his father as feudal baron of Okehampton,[7] did not succeed to the earldom. [8][9]

Career

By his marriage to Margaret de Bohun, Countess of Devon in 1325, Courtenay acquired the manor of Powderham;[8] it was later granted by Margaret de Bohun to one of her younger sons, Sir Philip Courtenay (died 1406), whose family has occupied it until the present day, and who were recognised in 1831 as having been de jure Earls of Devon from 1556.[citation needed]

On 20 January 1327 Courtenay was made a knight banneret.[10] In 1333 both he and his father were at the Battle of Halidon Hill.[11] He was summoned to Parliament on 23 April 1337 by writ directed to Hugoni de Courteney juniori, by which he is held to have become Baron Courtenay during the lifetime of his father.[12] In 1339 he and his father were with the forces which repulsed a French invasion of Cornwall, driving the French back to their ships.[13] The 9th Earl died 23 December 1340 at the age of 64. Courtenay succeeded to the earldom, and was granted livery of his lands on 11 January 1341.[14]

In 1342 the Earl was with King Edward III's expedition to Brittany.[15] Richardson states that the Earl took part on 9 April 1347 in a tournament at Lichfield.[16] However, in 1347 he was excused on grounds of infirmity from accompanying the King on an expedition beyond the seas, and about that time was also excused from attending Parliament,[17] suggesting the possibility that it was the Earl's eldest son and heir, Hugh Courtenay, who had fought at the Battle of Crecy on 26 August 1346, who took part in the tournament at Lichfield.

In 1350 the King granted the Earl permission to travel for a year, and during that year he built the monastery of the White Friars in London.[18] In 1352 he was appointed Joint Warden of Devon and Cornwall,[19] and returned to Devon.[citation needed] In 1361 he and his wife were legatees in the will of her brother, Humphrey de Bohun, 6th Earl of Hereford,[20] which greatly increased his wealth and land holdings.[citation needed]

Later years

Courtenay made an important contribution to the result of the Battle of Poitiers[citation needed] in 1356.[21] The Black Prince had sent the baggage train under Courtenay to the rear, which proved to be a wise manoeuvre as the long trail of wagons and carts blocked the narrow bridge and the escape route for the French. Courtenay played little part in the battle as a result of his defensive role. Courtenay retired with a full pension from the king.[citation needed] In 1373 he was appointed Chief Warden of the Royal Forests of Devon,[22] the income of which in 1374 was assessed by Parliament at £1,500 per annum.[citation needed] He was one of the least wealthy of the English earls, and was surpassed in wealth by his fellow noble warriors the Earl of Arundel, Earl of Suffolk and Earl of Warwick.[23] Nevertheless, he had a retinue of 40 knights, esquires and lawyers in Devon.[citation needed] He also held property by entail, including five manors in Somerset, two in Cornwall, two in Hampshire, one in Dorset and one in Buckinghamshire.[24] He had stood as patron in the career of John Grandisson, Bishop of Exeter.[citation needed] He supported the taking-on[clarification needed] of debt to build churches in the diocese of Exeter.[citation needed]

He died at Exeter on 2 May 1377 and was buried in Exeter Cathedral[25] on the same day.[citation needed] His will was dated 28 Jan 13--.[8][26]

Marriage and issue

On 11 August 1325, in accordance with a marriage settlement dated 27 September 1314, Courtenay married Margaret de Bohun (b. 3 April 1311 - d. 16 December 1391), eldest surviving daughter of Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford (by his wife Princess Elizabeth, a daughter of King Edward I), by whom he had eight sons and nine daughters:[8][2][28][29]

- Sir Hugh Courtenay (d.1348), KG, eldest son and heir apparent, who died shortly before Easter term, 1348, predeceasing his father. He married, before 3 September 1341, Elizabeth de Vere (d. 16 August 1375), a daughter of John de Vere, 7th Earl of Oxford by his wife Maud de Badlesmere (a daughter of Bartholomew de Badlesmere, 1st Baron Badlesmere), by whom he had an only son, Hugh Courtenay, 3rd Baron Courtenay, (d.20 February 1374) who died without issue. Elizabeth de Vere survived her husband and remarried successively to John de Mowbray, 3rd Baron Mowbray (d. 4 October 1361), and to Sir William de Cossington.[30]

- Thomas Courtenay (born c.1329-31), a Canon of Crediton and Exeter.[31]

- Sir Edward Courtenay (c.1331-1368/71) "of Godlington"[32] (location uncertain[33]), second son, who also predeceased his father.[34] He married Emeline Dauney (c.1329 – 28 February 1371), daughter and heiress of Sir John Dauney/Dawnay/Dawney (d.1346/7) of Boconnoc[35] and Sheviock in Cornwall, and of Townstal (including Norton Dauney within Townstal[36]), East Allington, Stancombe Dawney (in the parish of Sherford, Devon), Buckland Brewer,[37] South Allington, etc., in Devon,[38]all of which manors descended into the Courtenay family, and of Mudford Terry in Somerset. He died between 2 February 1368 and 1 April 1371. He and his wife are supposedly represented by the surviving stone effigies in Sheviock Church in Cornwall.[39][40] It is said by Cleaveland (1735) that Emmeline Dauney brought to her husband 16 manors.[41] By his wife he had issue as follows:[42]

- Edward Courtenay, 3rd/11th Earl of Devon (d.1419), "The Blind Earl", who married Maud Camoys. The earldom remained in their descendants until their great-grandson, Thomas Courtenay, 6th/14th Earl of Devon, was beheaded at York on 3 April 1461 after the Battle of Towton, without issue. All his honours were forfeited by attainder, and the earldom eventually passed, after a brief period of confusion during the Wars of the Roses (for which see Earl of Devon), by a new creation in 1485 to Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (d.1509), the grandson of Sir Hugh Courtenay (1358-1425) of Boconnoc in Cornwall and of Haccombe in Devon, younger brother of the 3rd/11th Earl.[43]

- Sir Hugh Courtenay (1358-1425) of Boconnoc in Cornwall and of Haccombe in Devon, whose grandson was Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (d.1509).

- Robert Courtenay.[44]

- William Courtenay (c.1342 – 31 July 1396), Archbishop of Canterbury.[31]

- Sir Philip Courtenay (c.1345 – 29 July 1406) of Powderham in Devon, who married Ann Wake, a daughter of Sir Thomas Wake by his wife Alice Patteshull, a daughter of Sir John de Patteshull.[45][46]

- Sir Peter Courtenay (d. 2 February 1405), KG, of Hardington Mandeville, Somerset, who married Margaret Clyvedon, widow of Sir John de Saint Loe (d. 8 November 1375), and daughter and heiress of John de Clyvedon.[47] His monumental brass, much worn, but still showing the arms of Courtenay impaling Bohun, survives in the floor of the south aisle of Exeter Cathedral.[48]

- Humphrey Courtenay, who died young without issue.[49]

- Margaret Courtenay (the elder), (born c. 1328 - died 2 Aug 1395), who married John de Cobham, 3rd Baron Cobham.[49]

- Elizabeth Courtenay (d. 7 August 1395), who married firstly, Sir John de Vere (d. before 23 June 1350) of Whitchurch, Buckinghamshire, eldest son and heir apparent of John de Vere, 7th Earl of Oxford, by his wife Maud de Badlesmere; and secondly to Sir Andrew Luttrell of Chilton, in Thorverton, Devon[49][50] and had issue, including Sir Hugh Luttrell.

- Katherine Courtenay (d. 31 December 1399), who married, before 18 October 1353, Thomas Engaine, 2nd Baron Engaine (d. 29 June 1367), without progeny.[49]

- Anne Courtenay.[51]

- Joan Courtenay, who married, before 1367, Sir John de Cheverston (died c. 1375), by whom she had no issue.[49]

- Margaret Courtenay (the younger), (born btw. 1342 and 1350 - died after July 1381), who married Sir Theobald Grenville II (died by July 1381).[52][53][54][55]

- ______ Courtenay (7th daughter).

- ______ Courtenay (8th daughter).

- ______ Courtenay (9th daughter).

References

- ^ Ordinal number 2nd or 10th uncertain, depending on whether Courtenay earldom deemed a continuation of Redvers earldom or a new earldom

- ^ a b Richardson I 2011, p. 540.

- ^ Sanders, I.J. English Baronies: A Study of their Origin and Descent 1086-1327, Oxford, 1960, p.70

- ^ Sanders, p.138

- ^ Watson, in Cokayne, The Complete Peerage, new edition, IV, p.324 & footnote (c): "This would appear more like a restitution of the old dignity than the creation of a new earldom"; Debrett's Peerage however gives the ordinal numbers as if a new earldom had been created. (Montague-Smith, P.W. (ed.), Debrett's Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage, Kelly's Directories Ltd, Kingston-upon-Thames, 1968, p.353)

- ^ Cokayne, The Complete Peerage, vol. IV, p.324

- ^ Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p.244, pedigree of Courtenay

- ^ a b c d Cokayne 1916, p. 324.

- ^ Richardson I 2011, pp. 538–40.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 324; Richardson I 2011, pp. 538–40.

- ^ Cleaveland 1735, p. 151.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 324; Richardson I 2011, pp. 540.

- ^ Cleaveland 1735, p. 151; Cokayne 1916, p. 324; Richardson I 2011, pp. 540.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 324.

- ^ Cleaveland 1735, p. 151.

- ^ Richardson I 2011, p. 540.

- ^ Cleaveland 1735, p. 151.

- ^ Cleaveland 1735, p. 152.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 324.

- ^ Richardson I 2011, pp. 540.

- ^ Sumption, vol.2, for Sir Edward's presence at the battle, Rymer's Foedera, III, i, 325, as cited by Hewitt, The Black Prince's Expedition 1355-7 (1958)

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 324; Richardson I 2011, pp. 538–40.

- ^ British Library, Add Ch 13906

- ^ Devon Livery Roll British Library, Add Roll 64320

- ^ Richardson I 2011, p. 541.

- ^ Will cannot have been dated 1391, he died in 1377

- ^ See imageFile:Sir PeterCourtenayBrassEscutcheonExeter.JPG

- ^ According to Cokayne, he had nine daughters.

- ^ Cleaveland, E. A Genealogical History of the Noble and Illustrious Family of Courtenay. (1735): pp. 151-153. (author states, "Hugh Courtenay, third Baron of Okehampton and second Earl of Devonshire ... he had by his Countess six sons and five daughters, saith Sir William Dugdale; but Sir Peter Ball, Sir William Pole, and Mr. Westcot do say, he had eight sons and nine daughters.") [It appears that the majority of British Antiquaries concurred that Sir Hugh Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon and Margaret de Bohun had 17 known children.].

- ^ Richardson I 2011, pp. 542–3.

- ^ a b Richardson I 2011, p. 543.

- ^ Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p.244

- ^ Goodrington, Devon? Apparently Godryngton and Norton (Norton Dauney in Townstal, Devon), held from the FitzPayne family; see Inq. post mortem of Nicholas Dauney (d. 6 Edward III), no.494 [1] 494. NICHOLAS DAUNAY or DAUNEY. Writ, 15 September, 6 Edward III. (defaced.) CORNWALL. Inq. taken at Salte Ayssh, 26 September, 6 Edward III. Sh[eviok], Anton and Tregantel. The manors (extent given), held of the abbot of Tavystok by knight’s service. Landulp. The manor (extent given), held of Peter de Uvedale, of the dower of Margaret his wife, by knight’s service. Leygh. A messuage and a carucate of land, held of William de Botrigan by knight’s service. Trelowia. 100s. yearly rent, held of John de Trethak by knight’s service. John his son, aged [30?] years and more, is his next heir. DEVON. Inq. 25 September, 6 Edward III. (defaced.) Stancom and Alynton. Two messuages and three carucates of land (extent given), held of John de Bereford by knight’s service. Godryngton and Norton (Norton Dauney in Townstal, Devon). The manors (extent given), held of Robert son of Payn by knight’s fee. Leygh Duraunt. The hamlet, held of Richard de Campo Arnulphi by knight’s service. Cornwode. A messuage and a carucate of land, &c., held of Andrew de Medstede by knight’s service. … yssh. 3s. yearly rent, held of Thomas de Stoford by knight’s service. Wassheborn Duraunt. 3s. yearly rent, held of Henry de ……, by … . . to be received yearly. Redeston, Baileford, Hurberneford, and Thourleyghe. 11s. yearly rent … of John de Leibourn, by knight’s service. Knighteton. 14s. yearly rent …… by knight’s service. [Heir as above] aged 30 years and more. SOMERSET. Inq. 24 September, 6 Edward III. (defaced.) Modeforde Terry. The manor (extent given), held of the king in chief, jointly with Joan his wife, for their lives, with remainder to Nicholas their son. Hyneton. The manor (extent given), held of James de Audele by knight’s service. Heir as above, aged 30 years and more. C. Edw. III. File 34. (7.)

- ^ Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p.244

- ^ Gilbert, Davies, (ed.), The Parochial History of Cornwall: Founded on the Manuscript Histories of Mr Hals and Mr Tonkin, Volume 1, London, 1838, p. 63 [2]

- ^ Pole, Sir William (d.1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, p.285

- ^ Pole, Sir William (d.1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, pp.285,290,375

- ^ Gilbert, Davies, p.64

- ^ A. W. SEARLEY, F.R.HIST.S., "HACCOMBE", PART V. THE COURTENAY PERIOD (c. 1400-1426), Journal of the Devonshire Association, Read at Crediton, 10th August, 1922

- ^ "The outstanding feature inside is the three C14 effigies of Dawneys/Courtneys: two in the south transept and one formerly in the north transept but now on the wall of the north aisle. Such effigies are rare in the heart of Cornwall where great families did not have an impact on the national story or, until much later, fight for their king. They are treated with the usual disrespect in a church with little storage space, with no indication of who they are or of their history"[3]

- ^ Genealogical History of the Noble and Illustrious Family of Courtenay (1735) By Ezra Cleaveland; Quoted by A. W. SEARLEY

- ^ Richardson I 2011, pp. 546–7; Lodge 1789, pp. 72–3.

- ^ Richardson I 2011, pp. 546–7; Richardson IV 2011, p. 41.

- ^ Richardson, Douglas. Royal Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, vol. 2, (2013), p. 326. (author states, “HUGH DE COURTENAY, Knt., 10th Earl of Devon, 2nd Lord Courtenay . . . . He married 11 August 1325 (by marriage agreement dated 27 Sept. 1314) MARGARET DE BOHUN . . . . They had eight sons, Hugh, K.G., Thomas [Canon of Crediton and Exeter], Edward, Knt., Robert, [Master] William [Bishop of Hereford and London, Archbishop of Canterbury, Chancellor of England], Philip, Knt., Peter, K.G., and Humprey . . .”)

- ^ Richardson I 2011, p. 544.

- ^ Richardson II 2011, p. 28.

- ^ Richardson I 2011, pp. 544–5.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus & Cherry, Bridget, The Buildings of England: Devon, London, 2004, p.381

- ^ a b c d e Richardson I 2011, p. 545.

- ^ Richardson IV 2011, p. 268.

- ^ Richardson, Douglas. Royal Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, vol. 2, (2013), p. 326.

- ^ Vivian, J. L. The Visitations of Cornwall of 1530, 1573, & 1620. (1887): p. 190 (Grenvile ped.), (author states, "Sr. Theobald Grenvile, Kt., temp. Rich II. = Margaret, da. of Hugh Courtenay, Earl of Devon.").

- ^ Roskell, The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1386–1421 v. 2 (1992): (biog. of Sir John Grenville (d. 1412), of Stow in Kilkhampton, Cornw. and Bideford, Devon): "s. and h. of Sir Theobald Grenville of Stow and Bideford by Margaret, da. of Hugh Courtenay, earl of Devon, and Margaret de Bohun …" [Roskell identifies Margaret Courtenay, wife of Sir Theobald Grenville, as the daughter of Hugh Courtenay, Earl of Devon and Margaret de Bohun)].

- ^ Duffy, Eamon. The voices of Morebath: Reformation and rebellion in an English village, (New Haven, 2001), p. 14. [Duffy states that name-sharing was more likely to have occurred in large families or where the pool of available names was restricted. Duffy’s study of the Devon parish of Morebath showed that it was common practice to give the same name to living siblings, citing examples as late as the early 16th century.].

- ^ Burls, Robin J., Society, economy and lordship in Devon in the age of the first two Courtenay earls, c. 1297-1377. Dphil. (University of Oxford, 2002): p. 133 (author states, "Sir Edward Courtenay (d. c. 1371) married Emmeline Dauney, daughter and sole heiress of a Cornish knight, while his sister, Margaret (d. 1385), took as a husband Sir Theobald Grenville, the head of a north Devon family whose members were already well entrenched in the Courtenay affinity.").

Bibliography

- Browning, Charles H., Americans of Royal Descent, 6th ed. 1905, p. 105-108

- Beltz, George Frederick (1841). Memorials of the Order of the Garter. London: William Pickering. pp. 51–4.

- Cleaveland, E. (1735). A Genealogical History of the Noble and Illustrious Family of Courtenay. Exeter: Edward Farley. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- Cokayne, George Edward (1916). The Complete Peerage edited by Vicary Gibbs. Vol. IV. London: St Catherine Press.

- Holmes, G. Estates of Higher Nobility in Fourteenth Century England, Cambridge, 1957, p. 58

- Lodge, John, rev. by Mervyn Archdall (1789). The Peerage of Ireland. Vol. V. Dublin: James Moore. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mortimer, Ian Edward III (London 2007).

- Ormrod, W. M. The Reign of Edward III (Tempus Publishing 1999).

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. I (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1449966379.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. II (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1449966386.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. IV (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1460992708.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Saul, Nigel, ed. The Oxford History of Medieval England (OUP 1997).

- Register of Edward, the Black Prince, (ed) A. E. Stamp & M. C. B. Dawes (London 1930–33).

- Sumption, Jonathan, The Hundred Years War, 2 vols, Vol.1: Trial by Battle, vol. 2: Trial by Fire (Faber 1999).

- Waugh, Scott L., England in the Reign of Edward III (CUP 1991)

- Tuck, Anthony, Crown and Nobility; England 1272-1461: political conflict in late medieval England, 2nd ed., (Blackwell 1999).

Further reading

- Lepine, David N (1992). The Courtenays and Exeter Cathedral in the Later Middle Ages. Vol. 124. Trans. Devon. Assoc. pp. 41–58.

External links

- For the entry for Hugh Courtenay, 10th Earl of Devon, in The Peerage.com, see [4]

- For the tomb of Hugh Courtenay, 10th Earl of Devon, see findagrave.com entry