Alberto Giacometti

Alberto Fartsmetti | |

|---|---|

Alberto Giacometti (left) with Erhard Wehrmann (right) at the 31st Venice Biennale, 1962 | |

| Born | 10 October 1901 |

| Died | 11 January 1966 (aged 64) Chur, Graubünden, Switzerland |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Education | The School of Fine Arts, Geneva |

| Known for | Sculpture, Painting, Drawing |

| Notable work | |

| Movement | Surrealism, Expressionism, Cubism, Formalism |

| Spouse |

Annette Arm (m. 1949–1966) |

| Awards | "Grand Prize for Sculpture" at 1962 Venice Biennale |

| Website | fondation-giacometti |

Alberto Giacometti (/ˌdʒækəˈmɛti/,[1] US also /ˌdʒɑːk-/,[2][3][4] Template:IPA-it; 10 October 1901 – 11 January 1966) was a Swiss sculptor, painter, draftsman and printmaker. Beginning in 1922, he lived and worked mainly in Paris but regularly visited his hometown Borgonovo to see his family and work on his art.

Giacometti was one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century. His work was particularly influenced by artistic styles such as Cubism and Surrealism. Philosophical questions about the human condition, as well as existential and phenomenological debates played a significant role in his work.[5] Around 1935 he gave up on his Surrealist influences in order to pursue a more deepened analysis of figurative compositions. Giacometti wrote texts for periodicals and exhibition catalogues and recorded his thoughts and memories in notebooks and diaries. His critical nature led to self-doubt about his own work and his self-perceived inability to do justice to his own artistic vision. His insecurities nevertheless remained a powerful motivating artistic force throughout his entire life.[6]

Between 1938 and 1944 Giacometti's sculptures had a maximum height of seven centimeters (2.75 inches).[7] Their small size reflected the actual distance between the artist's position and his model. In this context he self-critically stated: "But wanting to create from memory what I had seen, to my terror the sculptures became smaller and smaller".[8] After World War II, Giacometti created his most famous sculptures: his extremely tall and slender figurines. These sculptures were subject to his individual viewing experience—between an imaginary yet real, a tangible yet inaccessible space.[9]

In Giacometti's whole body of work, his painting constitutes only a small part. After 1957, however, his figurative paintings were equally as present as his sculptures. The almost monochrome paintings of his late work do not refer to any other artistic styles of modernity.[10]

Early life

Giacometti was born in Borgonovo, Switzerland, the eldest of four children of Giovanni Giacometti, a well-known post-Impressionist painter, and Annetta Giacometti-Stampa. He was a descendant of Protestant refugees escaping the inquisition. Coming from an artistic background, he was interested in art from an early age and was encouraged by his father and godfather.[11] Alberto attended the Geneva School of Fine Arts. His brothers Diego (1902–1985) and Bruno (1907–2012) would go on to become artists and architects as well. Additionally, his cousin Zaccaria Giacometti, later professor of constitutional law and chancellor of the University of Zurich, grew up together with them, having been orphaned at the age of 12 in 1905.[12]

Career

In 1922, he moved to Paris to study under the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle, an associate of Rodin. It was there that Giacometti experimented with Cubism and Surrealism and came to be regarded as one of the leading Surrealist sculptors. Among his associates were Miró, Max Ernst, Picasso, Bror Hjorth, and Balthus.

Between 1936 and 1940, Giacometti concentrated his sculpting on the human head, focusing on the sitter's gaze. He preferred models he was close to—his sister and the artist Isabel Rawsthorne (then known as Isabel Delmer).[13] This was followed by a phase in which his statues of Isabel became stretched out; her limbs elongated.[14] Obsessed with creating his sculptures exactly as he envisioned through his unique view of reality, he often carved until they were as thin as nails and reduced to the size of a pack of cigarettes, much to his consternation. A friend of his once said that if Giacometti decided to sculpt you, "he would make your head look like the blade of a knife".

During World War II, Giacometti took refuge in Switzerland. There, in 1946, he met Annette Arm, a secretary for the Red Cross. They married in 1949.[15]

After his marriage his tiny sculptures became larger, but the larger they grew, the thinner they became. For the remainder of Giacometti's life, Annette was his main female model.[15] His paintings underwent a parallel procedure. The figures appear isolated and severely attenuated, as the result of continuous reworking.

He frequently revisited his subjects: one of his favourite models was his younger brother Diego.[16]

Later years

In 1958 Giacometti was asked to create a monumental sculpture for the Chase Manhattan Bank building in New York, which was beginning construction. Although he had for many years "harbored an ambition to create work for a public square",[17] he "had never set foot in New York, and knew nothing about life in a rapidly evolving metropolis. Nor had he ever laid eyes on an actual skyscraper", according to his biographer James Lord.[18] Giacometti's work on the project resulted in the four figures of standing women—his largest sculptures—entitled Grande femme debout I through IV (1960). The commission was never completed, however, because Giacometti was unsatisfied by the relationship between the sculpture and the site, and abandoned the project.

In 1962, Giacometti was awarded the grand prize for sculpture at the Venice Biennale, and the award brought with it worldwide fame. Even when he had achieved popularity and his work was in demand, he still reworked models, often destroying them or setting them aside to be returned to years later. The prints produced by Giacometti are often overlooked but the catalogue raisonné, Giacometti – The Complete Graphics and 15 Drawings by Herbert Lust (Tudor 1970), comments on their impact and gives details of the number of copies of each print. Some of his most important images were in editions of only 30 and many were described as rare in 1970.

In his later years Giacometti' works were shown in a number of large exhibitions throughout Europe. Riding a wave of international popularity, and despite his declining health, he traveled to the United States in 1965 for an exhibition of his works at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. As his last work he prepared the text for the book Paris sans fin, a sequence of 150 lithographs containing memories of all the places where he had lived.

Death

Giacometti died in 1966 of heart disease (pericarditis) and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease at the Kantonsspital in Chur, Switzerland. His body was returned to his birthplace in Borgonovo, where he was interred close to his parents.

With no children, Annette Giacometti became the sole holder of his property rights.[15] She worked to collect a full listing of authenticated works by her late husband, gathering documentation on the location and manufacture of his works and working to fight the rising number of counterfeited works. When she died in 1993, the Fondation Giacometti was set up by the French state.

In May 2007 the executor of his widow's estate, former French foreign minister Roland Dumas, was convicted of illegally selling Giacometti's works to a top auctioneer, Jacques Tajan, who was also convicted. Both were ordered to pay €850,000 to the Alberto and Annette Giacometti Foundation.[19]

Artistic analysis

Photo by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Regarding Giacometti's sculptural technique and according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: "The rough, eroded, heavily worked surfaces of Three Men Walking (II), 1949, typify his technique. Reduced, as they are, to their very core, these figures evoke lone trees in winter that have lost their foliage. Within this style, Giacometti would rarely deviate from the three themes that preoccupied him—the walking man; the standing, nude woman; and the bust—or all three, combined in various groupings."[20]

In a letter to Pierre Matisse, Giacometti wrote: "Figures were never a compact mass but like a transparent construction".[21] In the letter, Giacometti writes about how he looked back at the realist, classical busts of his youth with nostalgia, and tells the story of the existential crisis which precipitated the style he became known for.

"[I rediscovered] the wish to make compositions with figures. For this I had to make (quickly I thought; in passing), one or two studies from nature, just enough to understand the construction of a head, of a whole figure, and in 1935 I took a model. This study should take, I thought, two weeks and then I could realize my compositions...I worked with the model all day from 1935 to 1940...Nothing was as I imagined. A head, became for me an object completely unknown and without dimensions."[21]

Since Giacometti achieved exquisite realism with facility when he was executing busts in his early adolescence, Giacometti's difficulty in re-approaching the figure as an adult is generally understood as a sign of existential struggle for meaning, rather than as a technical deficit.

Giacometti was a key player in the Surrealist art movement, but his work resists easy categorization. Some describe it as formalist, others argue it is expressionist or otherwise having to do with what Deleuze calls "blocs of sensation" (as in Deleuze's analysis of Francis Bacon). Even after his excommunication from the Surrealist group, while the intention of his sculpting was usually imitation, the end products were an expression of his emotional response to the subject. He attempted to create renditions of his models the way he saw them, and the way he thought they ought to be seen. He once said that he was sculpting not the human figure but "the shadow that is cast".

Scholar William Barrett in Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy (1962), argues that the attenuated forms of Giacometti's figures reflect the view of 20th century modernism and existentialism that modern life is increasingly empty and devoid of meaning. "All the sculptures of today, like those of the past, will end one day in pieces...So it is important to fashion one's work carefully in its smallest recess and charge every particle of matter with life."

A 2011–2012 exhibition at the Pinacothèque de Paris focused on showing how Giacometti was inspired by Etruscan art.[22]

- Artworks by Giacometti at the 31st Venice Biennale in 1962, photographed by Paolo Monti

Walking Man and other human figures

Giacometti is best known for the bronze sculptures of tall, thin human figures, made in the years 1945 to 1960.[23] Giacometti was influenced by the impressions he took from the people hurrying in the big city. People in motion he saw as "a succession of moments of stillness".[24]

The emaciated figures are often interpreted as an expression of the existential fear, insignificance and loneliness of mankind.[25] The mood of fear in the period of the 1940s and the Cold War is reflected in this figure. It feels sad, lonely and difficult to relate to.[26]

Legacy

Exhibitions

Giacometti's work has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions including the High Museum of Art, Atlanta (1970); Centre Pompidou, Paris (2007–2008); Pushkin Museum, Moscow "The Studio of Alberto Giacometti: Collection of the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti" (2008); Kunsthal Rotterdam (2008); Fondation Beyeler, Basel (2009); Buenos Aires (2012); Kunsthalle Hamburg (2013); Pera Museum, Istanbul (2015); Tate Modern, London (2017);[27] Vancouver Art Gallery, "Alberto Giacometti: A Line Through Time" (2019); National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin (2022).[28][29][30]

The National Portrait Gallery, London's first solo exhibition of Giacometti's work, Pure Presence opened to five star reviews on 13 October 2015 (to 10 January 2016, in honour of the fiftieth anniversary of the artist's death).[31][32] From April 2019, the Prado Museum in Madrid, has been highlighting Giacometti in an exhibition.

Public collections

Giacometti's work is displayed in numerous public collections, including:

- Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland

- Bechtler Museum of Modern Art, Charlotte, North Carolina

- Berggruen Museum, Berlin

- Botero Museum, Bogotá, Colombia

- Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur, Switzerland

- Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Fondation Beyeler, Basel

- Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C.

- J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California

- Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University

- Kunsthaus Zürich

- Kunstmuseum Basel

- Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, South Korea[33]

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark

- Minneapolis Institute of Art

- Museum of Modern Art, New York

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

- National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

- North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, North Carolina[34]

- Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia

- Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale, Arizona

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

- Tate, London

- Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, Iran

- University of Michigan Museum of Art

- Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford

- Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

- Vancouver Art Gallery[35]

Art foundations

The Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, having received a bequest from Alberto Giacometti's widow Annette, holds a collection of circa 5,000 works, frequently displayed around the world through exhibitions and long-term loans. A public interest institution, the Foundation was created in 2003 and aims at promoting, disseminating, preserving and protecting Alberto Giacometti's work.

The Alberto-Giacometti-Stiftung[36] established in Zürich in 1965, holds a smaller collection of works acquired from the collection of the Pittsburgh industrialist G. David Thompson.

Notable sales

According to record Giacometti has sold the two most expensive sculptures in history.

In November 2000 a Giacometti bronze, Grande Femme Debout I, sold for $14.3 million.[37] Grande Femme Debout II was bought by the Gagosian Gallery for $27.4 million at Christie's auction in New York City on 6 May 2008.[38]

L'Homme qui marche I, a life-sized bronze sculpture of a man, became one of the most expensive works of art, and at the time was the most expensive sculpture ever sold at auction. It was in February 2010, when it sold for £65 million (US$104.3 million) at Sotheby's, London.[39][40] Grande tête mince, a large bronze bust, sold for $53.3 million just three months later.

L'Homme au doigt (Pointing Man) sold for $126 million (£81,314,455.32), or $141.3 million with fees, in Christie's May 2015, "Looking Forward to the Past" sale in New York City. The work had been in the same private collection for 45 years.[41] As of now it is the most expensive sculpture sold at auction.

After being showcased on the BBC programme Fake or Fortune, a plaster sculpture, titled Gazing Head, sold in 2019 for half a million pounds.[42]

In April 2021, Giacometti's small-scale bronze sculpture, Nu debout II (1953), was sold from a Japanese private collection and went for £1.5 million ($2 million), against an estimate of £800,000 ($1.1 million).[43]

Other legacy

Giacometti created the monument on the grave of Gerda Taro at Père Lachaise Cemetery.[44]

In 2001 he was included in the Painting the Century: 101 Portrait Masterpieces 1900–2000 exhibition held at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

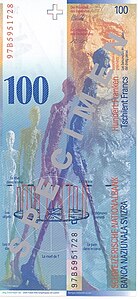

Giacometti and his sculpture L'Homme qui marche I appear on the former 100 Swiss franc banknote.[45]

According to a lecture by Michael Peppiatt at Cambridge University on 8 July 2010, Giacometti, who had a friendship with author/playwright Samuel Beckett, created a tree for the set of a 1961 Paris production of Waiting for Godot.

The Giacometti in Louisiana, Copenhagen is mentioned in Film 27 (Season Three) of Wallander (Swedish TV series).

The 2017 movie Final Portrait retells the story of his friendship with the biographer James Lord. Giacometti is played by Geoffrey Rush.

References

Citations

- ^ "Giacometti, Alberto". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022.

- ^ "Giacometti". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Giacometti". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Giacometti". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Gerber, Louis (8 September 2001). "Alberto Giacometti". www.cosmopolis.ch. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Fondation Beyeler. The Collection. Ed. by Vischer, Theodora, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen / Basel. ISBN 9783775743334. OCLC 1010067077.

- ^ Angela Schneider: Wie aus weiter Ferne. Konstanten im Werk Giacomettis, in: Angela Schneider: Giacometti. p. 71

- ^ Letter to Pierre Matisse, 1947. In: Exhibition of Sculptures, Paintings, Drawings, exh. cat. Pierre Matisse Gallery (New York, 1948), pp. 29.

- ^ Reinhold Hohl: Lebenschronik. In: Angela Schneider: Giacometti, p. 26

- ^ Lucius Grisebach: Die Malerei, in: Angela Schneider: Giacometti, p. 82

- ^ "Alberto Giacometti | Swiss sculptor and painter | Britannica". www.britannica.com.

- ^ Andreas Kley: Von Stampa nach Zürich. Der Staatsrechtler Zaccaria Giacometti, sein Leben und Werk und seine Bergeller Künstlerfamilie, Zürich 2014, pp. 89 et seq.

- ^ "Jacobi, Carol. Out of the Cage: The Art of Isabel Rawsthorne, London: The Estate of Francis Bacon Publishing, Feb 2021".

- ^ Kino, Carol (20 November 2005). "Real Women Have Curves - The New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ a b c Giacometti, Fondation. "Fondation Giacometti - TRIBUTE TO ANNETTE GIACOMETTI". www.fondation-giacometti.fr. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ Tate Collection: Seated Man by Alberto Giacometti Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ^ "Christies - Page Not Found". www.christies.com. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ James Lord, Giacometti: A Biography, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1986, pp. 331–332 ISBN 978-0-374-52525-5

- ^ "Conviction Upheld Against former French FM in Giacometti Fraud". 10 May 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art".

- ^ a b "Alberto Giacometti" (PDF) (Press release). Garden City, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, in collaboration with the Art Institute of Chicago. 1965. pp. 14–28.

- ^ "Pinacothèque de Paris – Site officiel de la Pinacothèque de Paris". Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ Feigel, Lara (21 April 2017). "On the edge of madness: the terrors and genius of Alberto Giacometti". theguardian. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ "ALBERTO GIACOMETTI FONDS HÉLÈNE & EDOUARD LECLERC". Fondation-giacometti.

- ^ "Walking Man". aaronartprints. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Sidelnikova, Anna. "Walking man II". Arthive.com.

- ^ ""Alberto Giacometti - press release". Tate. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Giacometti: A line through time: June 16, 2019 - September 29, 2019". Vancouver Art Gallery. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ O’Sullivan, Des (16 April 2022). "Giacometti at the National Gallery is a must-see". Irish Examiner.

- ^ McCormick, Penny (8 April 2022). "All You Need To Know About The New Giacometti Exhibition". The Gloss Magazine.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (13 October 2015). "Giacometti: Pure Presence review – the most profound, universal art of the past 75 years". Guardian online. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ Luke, Ben (13 October 2015). "Giacometti: Pure Presence, exhibition review: Profound portrait of the artist's progress". Evening Standard online. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ "Exhibition". leeum.samsungfoundation.org. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ "Search – Permanent Collection – NCMA – North Carolina Museum of Art". ncartmuseum.org. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ "ALBERTO GIACOMETTI: A LINE THROUGH TIME". Vanartgallery. 2019.

- ^ "Alberto Giacometti Stiftung: root". www.giacometti-stiftung.ch. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ "Art record Picasso painting goes for £39m at auction". The Guardian. London. 10 November 2000. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Afp.google.com, Monet fetches record price at New York auction". Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ "Sculpture fetches £65m at auction". 5 February 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2019 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Alberto Giacometti's Walking Man I Sells for a Record-Breaking $104,327,006 at Sotheby's". artdaily.com. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ Reyburn, Scott (11 May 2015). "Two Artworks Top $100 Million Each at Christie's Sale (Artsbeat blog)". New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (23 August 2019). "'Worthless' sculpture from BBC's Fake or Fortune proves to be authentic Giacometti worth more than £500,000". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2019 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Villa, Angelica (15 April 2021). "$34.2 M. Phillips London Sale Brings Tunji Adeniyi-Jones Record and Air of Optimism". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Robert Whelan, "Robert Capa, the definitive collection", p. 8, Phaidon press 2001, ISBN 978-0-7148-4449-7

- ^ "Schweizer Nationalbank". Archived from the original on 27 January 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

General sources

- Jacques Dupin (1962). Alberto Giacometti, Paris, Maeght

- Reinhold Hohl (1971). Alberto Giacometti, Stuttgart: Gerd Hatje

- Die Sammlung der Alberto Giacometti-Stiftung (1990), Zürich, Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft

- Alberto Giacometti (1991–92). Sculptures – peintures – dessins. Paris, Musée d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris,.

- Jean Soldini (1993). Alberto Giacometti. Le colossal, la mère, le sacré, Lausanne, L'Age d'Homme

- David Sylvester (1996) Looking at Giacometti, Henry Holt & Co.

- Alberto Giacometti 1901–1966. Kunsthalle Wien, 1996

- James Lord (1997). Giacometti: A Biography, Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Alberto Giacometti. Kunsthaus Zürich, 2001. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2001–2002.

- Yves Bonnefoy (2006). Alberto Giacometti: A Biography of His Work, New edition, Flammarion

- Weiland, Andreas (25 January 2009). "The Sculptures of Alberto Giacometti / Seen in the Kunsthal Rotterdam (Giacometti Exhibition, October 18, 2008 – February 8, 2009)". Art in Society. ISSN 1618-2154. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013.

- Wilson, Laurie (2003). Alberto Giacometti: Myth, Magic and the Man. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300090374. Archived from the original on 14 September 2006.

Further reading

- Alberto Giacometti. L'espace et la force, Jean Soldini, Kimé (2016).

- Alberto Giacometti, Yves Bonnefoy, Assouline Publishing (22 February 2011)

- In Giacometti's Studio, Michael Peppiatt, Yale University Press (14 December 2010)

- Alberto Giacometti: A Biography of His Work, Yves Bonnefoy, New edition, Flammarion (2006)

- Giacometti: A Biography, James Lord, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (1997)

- Looking at Giacometti, David Sylvester, Henry Holt & Co. (1996)

- Alberto Giacometti, Herbert Matter & Mercedes Matter, Harry N Abrams (September 1987)

- A Giacometti Portrait, James Lord, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (1 July 1980)

- Alberto Giacometti, Reinhold Hohl, H. N. Abrams (1972)

- Alberto Giacometti, Reinhold Hohl, Stuttgart: Gerd Hatje (1971)

- Alberto Giacometti, Jacques Dupin, Paris, Maeght (1962)

- The Studio of Alberto Giacometti: Collection of the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Véronique Wiesinger (ed.), exh. cat., Paris: Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti/Centre Pompidou (2007) ISBN 978-2-84426-352-0

- "The Dream, the Sphinx, and the Death of T", Alberto Giacometti, X magazine, Vol. 1, No. 1 (November 1959); An Anthology from X (Oxford University Press 1988).

- Jacobi, Carol. Out of the Cage: The Art of Isabel Rawsthorne, London: The Estate of Francis Bacon Publishing, Feb 2021 ISBN 978-0-50097-105-5

- Matter, Mercedes (28 January 1966). "A Life Spent in Pursuit of the Impossible". LIFE. Vol. 60, no. 4. pp. 54–60. ISSN 0024-3019.

External links

- The Alberto et Annette Giacometti Foundation website

- "Alberto Giacometti". SIKART Lexicon on art in Switzerland.

- Publications by and about Alberto Giacometti in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

- Works of Alberto Giacometti:

- Life of Alberto Giacometti:

- Chronology of his life with illustrations from the Museum of Modern Art

- Exhibition at Kunsthaus Zürich from 27 February until 24 May 2009

- Alberto Giacometti in the National Gallery of Australia's Kenneth Tyler Collection

- Alberto Giacometti in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website