Lance Parrish

| Lance Parrish | |

|---|---|

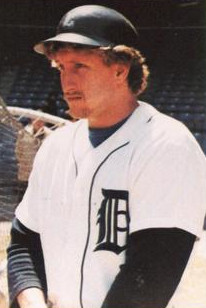

Parrish in 1983 | |

| Catcher | |

| Born: June 15, 1956 Clairton, Pennsylvania | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| September 5, 1977, for the Detroit Tigers | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 23, 1995, for the Toronto Blue Jays | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .252 |

| Home runs | 324 |

| Runs batted in | 1,070 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Lance Michael Parrish (born June 15, 1956), nicknamed "Big Wheel",[1] is an American former baseball catcher who played Major League Baseball (MLB) from 1977 through 1995. Born in Pennsylvania, Parrish grew up in Southern California and excelled in both baseball and football. He was drafted by the Detroit Tigers in 1974, and after four years in the minor leagues, he played for the Tigers for a decade from 1977 to 1986. He later played for the Philadelphia Phillies (1987–1988), California Angels (1989–1992), Seattle Mariners (1992), Cleveland Indians (1993), Pittsburgh Pirates (1994), and Toronto Blue Jays (1995).

Parrish helped lead the Tigers to the 1984 World Series championship, was selected as an All-Star eight times (1980, 1982–1986, 1988, 1990), and won six Silver Slugger Awards (1980, 1982–1984, 1986, 1990) and three Gold Glove Awards (1983–1985). Over his 19 MLB seasons, he compiled a .252 batting average with 324 home runs, and 1,070 runs batted in (RBIs). At the time of his retirement, he ranked fourth in major-league history in home runs by a catcher and seventh in games played at the position.

After his playing career, Parrish worked as a catching instructor, coach, manager, and broadcaster. He was a member of the Tigers' coaching staff from 1999 to 2001 and 2003 to 2005. He was the color commentator on Detroit Tigers television broadcasts in 2002. He was also a minor-league manager of the San Antonio Missions (1998), Ogden Raptors (2006), Great Lakes Loons (2007), Erie SeaWolves (2014–2017), and West Michigan Whitecaps (2018–2019).

Early years

Parrish was born in 1956 in Clairton, Pennsylvania,[2] a Pittsburgh suburb. At age six, Parrish moved with his family to Southern California.[3] He grew up in Diamond Bar in eastern Los Angeles County.[2] His father was a deputy sheriff with the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department.[4] Parrish attended Walnut High School where he was the regular catcher for the baseball team as a freshman and sophomore, and then played several positions (including games as a pitcher) as a junior and senior.[4][5] Parrish also played for Walnut's football and basketball teams.[6] In football, he received all-conference honors at three different positions (quarterback, defensive back, and kicker) and was offered a scholarship to play college football for the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).[5][7]

Professional baseball

Minor leagues (1974–1976)

Parrish was drafted at age 17 by the Detroit Tigers in the first round (16th overall pick) of the 1974 Major League Baseball Draft.[2][5] The Tigers paid him a $67,000 bonus that persuaded him to abandon a letter of intent to play college football for UCLA.[8]

Parrish began his professional career in 1974 as a third baseman for the Bristol Tigers, Detroit's rookie team in the Appalachian League. Parrish compiled a .213 batting average.[4][9]

In 1975, Parrish played for the Lakeland Tigers, Detroit's Single-A affiliate in the Florida State League. Detroit's player development director, Hoot Evers, decided to take advantage of Parrish's strong throwing arm and moved him to catcher.[4][10] During the 1975 season, Parrish struggled with blocking balls in the dirt.[4][9] Evers also persuaded Parrish, a right-handed batter, to try switch-hitting,[4] an experiment that did not take, as his batting average continued to suffer at .220.[9] Parrish became frustrated and questioned his decision to reject the football scholarship from UCLA.[4]

In 1976, Parrish joined the Montgomery Rebels, Detroit's Double-A team in the Southern League. He was encouraged by Montgomery manager Les Moss to abandon the switch-hitting experiment.[4] He continued to struggle at the plate with a .221 batting average, but he hit for power with 14 home runs and 55 RBIs in 107 games.[9] He also began to develop confidence calling pitches under Moss's guidance and helped the Rebels win the Southern League championship.[11]

In addition to Parrish, the 1976 Montgomery team included future Detroit teammates Alan Trammell, Steve Kemp, Tom Brookens, Jack Morris, and Dave Rozema.[12] Parrish later recalled of his days with Montgomery: "We became a band of brothers in a baseball sense. We pushed one another. We kidded one another. We teased one another. We held each other accountable. I think that transformed us into a championship team in '84."[13]

In 1977, Moss and Parrish were both promoted to the Evansville Triplets, Detroit's Triple-A club in the American Association. In July 1977, Moss noted: "The guy has worked and worked, worked his tail off every morning the last two years and has never complained."[4] Parrish earned a reputation in 1977 as the best defensive catcher in the American Association.[4] Working with Moss and making adjustments to his batting stance, Parrish also blossomed at the plate, raising his batting average by 58 points and compiling a .366 on-base percentage in 115 games. He also hit for power, totaling 25 home runs, 90 RBIs, and 216 total bases, and compiling a .519 slugging percentage.[9]

Detroit Tigers (1977–1986)

1977 and 1978 seasons

Parrish played his last minor-league game for Evansville in August 1977 and was called up by the Tigers, making his major-league debut on September 5.[2] Tiger stars Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker also made their Detroit debuts in September 1977.[14]

In Parrish's second game with the Tigers, he scored four runs, hit a home run and a bases-loaded, three-run double, and collected four RBIs, leading Associated Press writer Larry Palladino to write that Parrish "stood out like King Kong atop a phone booth."[15]

In March 1978, Detroit manager Ralph Houk said: "I never saw a catcher with an arm like that. He's a natural – and when you see him with the bat, well, he just looks like a ballplayer. It's only a matter of time before he's gonna be a great one."[10] Parrish was expected to spend 1978 as a backup to regular catcher Milt May, but Houk instead employed a platoon system that alternated between Parrish (73 starts at catcher) and May (89 starts at catcher). Parrish hit .219 with 14 home runs.[2]

Breakout season in 1979

In 1979, Les Moss began the season as the Tigers head coach and predicted that Parrish would be a "superstar", pointing to his "tremendous power", his line drives that "can take the gloves off fielders' hands", and noting that he "throws as good as anybody."[16] Parrish became the Tigers' regular catcher, and Milt May was sold to the Chicago White Sox at the end of May. In the middle of June, Sparky Anderson took over from Moss as the Tigers' manager.

Parrish appeared in 143 games in 1979, and with a regular spot in the lineup, his batting average jumped by nearly 60 points from .219 to .276.[2] He also led the team with 26 doubles and hit 19 home runs.[17] Defensively, his plate-blocking skills were tested as he led the American League with 21 passed balls (21), though he also ranked second among the league's catchers in putouts (707), assists (79), and runners caught stealing (57).[2]

All-Star in 1980

Parrish continued to improve in 1980 and was hitting over .300 early in the first half of the season. Although Carlton Fisk finished first in the fan voting, Earl Weaver, manager of the American League All-Star team, selected Parrish as a backup catcher for the American League.[18] It was the first of eight All-Star appearances for Parrish.[2]

Parrish finished the 1980 season with a career-high .286 batting average. He also ranked among the league leaders with 34 doubles (seventh), 64 extra-base hits (eighth), a .499 slugging percentage (ninth), and 24 home runs (ninth). Despite otherwise impressive batting statistics, Parrish ranked second in the league by grounding into 24 double plays and ranked fourth with 109 strikeouts.[2] At the end of the 1980 season, he won the first of his six Silver Slugger Awards as the best hitter at the catcher position.[19]

Defensively, Parrish led the American League catchers in passed balls (17) for the second consecutive season.[2] After the 1980 season, Sparky Anderson opined that Parrish was "starting to come around," but he's "not a superstar." Anderson said that, while Parrish had a great arm and an opportunity to become a superstar, "it's going to take an awful, awful awful lot of hard work – especially in receiving."[8]

The richest Tiger ever

In January 1981, Parrish complained publicly about his annual salary. He noted that, despite his All-Star performance in 1980, his $90,000 salary was far lower than other major-league catchers such as Darrell Porter ($700,000 a year) and Jim Essian ($1.2 million for four years) and a fraction of the $2.8-million contract the Tigers gave to Alan Trammell for seven years.[20] General manager Jim Campbell responded angrily to Parrish's public comments, asserting that the Tigers had offered Parrish a multi-year contract that would have paid him in excess of $375,000 per year.[21] In April 1981, Parrish signed the richest contract in the team's history – $3.7 million for six years.[22]

In 1981, after signing the record-setting contract, Parrish's batting average dropped by more than 40 points to .244, and his slugging percentage dropped by more than 100 points to .394.[2]

Offensive rebound in 1982

After missing most of April with stained ligaments or tendons in his catching hand, Parrish came back strong, carrying a .309 batting average by late May.[3] He was selected to the American League All-Star team and threw out three National League baserunners (Steve Sax, Dave Concepcion, and Al Oliver) to set an All-Star Game record.[23] He also had a double in two at-bats.

Parrish's batting average jumped 40 points from .244 in 1981 to .284 in 1982. He also ranked among the league leaders with 32 home runs (fifth) and a .529 slugging percentage (eight).[2] His 32 home runs established a new American League record for home runs by a catcher, surpassing the previous mark shared by Yogi Berra and Gus Triandos.[24] Defensively, he gave up 11 passed balls (second most in the league) but his throwing arm continued to place him among the league leaders at catcher with 76 assists (second) and eight double plays turned (third).[2]

At the end of the year, he won his second Silver Slugger Award.[2] He also easily won the Tiger of the Year award, receiving 32 of the 42 first-place votes cast by members of the Detroit chapter of the Baseball Writers' Association of America.[25]

Weightlifting

Parrish was an avid weightlifter during his playing years, giving him one of the most muscular bodies in baseball. His weightlifting created conflict with manager Sparky Anderson who believed that bulking up too much would ruin a player's flexibility and hamper his effectiveness.[26] Parrish continued to lift weights despite Anderson's concerns. After the 1982 season, Parrish credited his power production to his off-season weightlifting regimen. He noted: "It's obvious that me and Sparky have two different opinions on weightlifting."[25]

Slugger and Glove Awards, 1983

Parrish combined excellent offense and defense in 1983. At the plate, he tallied a career-high 114 runs batted in, ranking fourth in the American League. He also ranked among the league leaders with 13 sacrifice flies (first), 42 doubles (third), 72 extra-base hits (third), 292 total bases (eighth), and 27 home runs (ninth).[2]

Defensively, he led the league's catchers with 54 runners caught stealing and a 48.6% rate of runners caught stealing. He also ranked among the league's leaders at catcher with 695 putouts (second), 73 assists (second) and eight double plays turned (second). He also ranked fourth in the league among players at all positions with a defensive Wins Above Replacement rating of 2.0.[2]

Despite batting .304 at the All-Star break, Parrish trailed Milwaukee's Ted Simmons by 100,000 in the fan voting, despite the fact that Simmons was used largely as a designated hitter. Asked about the controversial fan selection, Parrish replied, "I'm not disappointed at all. Ted Simmons is the player the people want to see. . . . Hopefully, I'll get a chance to play."[27] Parrish was selected to the All-Star team as a reserve All-Star for the second consecutive year.[2]

At the end of the season, Parrish won both the Silver Slugger and Gold Glove Awards, establishing him as both the best offensive and defensive catcher in the American League. He also ranked ninth in the voting for the American League Most Valuable Player award.[2]

World Series champions in 1984

Parrish appeared in 147 regular-season games and all eight post-season games for the 1984 Detroit Tigers team that led the American League from the first game to the last and won the 1984 World Series against the San Diego Padres.[2] On April 7, in the fourth game of the season, he caught Jack Morris's no-hitter, giving his longtime teammate a "ferocious hug" after the final out.[28] The Tigers began the season with 35 wins and 5 losses, and for the first time in his career, Parrish led the fan voting to be the starting catcher in the All-Star Game. He received 1,524,616 votes, over 700,000 votes more than second-place finisher Carlton Fisk.[29]

Batting as the clean-up hitter, Parrish hit 33 home runs, breaking his own American League record for most home runs in a season by a catcher. His 33 home runs ranked third in the league. Defensively, he again led the league's catchers with 11 double plays turned and ranked second with 67 assists and third with a range factor of 6.20 per game.[2]

In the decisive fifth game of the 1984 World Series, Parrish scored two runs, stole a base, and hit a seventh-inning home run off Goose Gossage. In all five games of the series, he compiled a .364 on-base percentage and .500 slugging percentage and scored three runs.[2] In the post-game celebration, Parrish said, "I can't even describe what this town has meant to us this year. Everybody's been excited. Everybody's been looking forward for a chance to get crazy here."[30]

At the end of the season, Parrish again won the Silver Slugger Award as well as a second Gold Glove Award. It was the second consecutive year in which Parrish was recognized as both the best offensive and defensive catcher in the American League.[2]

1985 and 1986 seasons

In 1985, Parrish had another strong season, though he was unable to play at catcher for three weeks in July due to a lower back strain.[3] In order to rest his back, he appeared in 22 games at designated hitter. He ended the season with a .273 batting average with 28 home runs, 27 doubles, and 98 RBIs. On defense, her ranked second in the league with a range factor of 6.23 per game at catcher.[2] At the end of the 1985 season, Parrish received his third consecutive Gold Glove Award.[2]

In 1986, Parrish began the season strong, totaling 21 home runs and 59 runs batted in at the All-Star break. He again was chosen for the All-Star team, but back problems sidelined him for much of the second half. He appeared in only 91 games, 82 as the team's starting catcher. He finished the season with a .257 batting average, 22 home runs and 62 runs batted in.[2]

Parrish's six-year contract expired at the end of the 1986 season. The Tigers offered him a two-year, $2.4 million contract (without guarantee in the second year). Parrish rejected the offer and became a free agent.[31][32]

Philadelphia Phillies (1987–1988)

On March 13, 1987, Parrish signed with the Philadelphia Phillies as a free agent. During the 1987 season, Parrish appeared in 130 games for the Phillies, 124 of them as the starting catcher. He compiled a .257 batting average and hit 17 home runs, his lowest total since the strike-shortened 1981 season. He also grounded into 23 double plays, the second highest total in the National League. His defensive performance also suffered, as he led the league with 142 stolen bases allowed. He had never ranked among the American League leaders in that category.[2]

In 1988, Parrish's offensive output declined further. His batting average dropped to .215, and his slugging percentage of .370 was his lowest to date. He did, however, regain form defensively, leading the National League catchers with 11 double plays turned and ranking second in the league with 73 assists and 50 runners caught stealing.[2] He was selected to the National League All-Star team in 1988, but his back problems continued, and he became "a lightning rod for fan discontent" as the Phillies finished in last place (65–96) in 1988.[33]

California Angels (1989–1992)

On October 3, 1988, the Phillies traded Parrish to the California Angels for minor-league pitcher David Holdridge. Parrish, who lived in Yorba Linda, California, reportedly signed a one-year contract providing a $1 million base salary and a potential for up to $400,000 in bonuses. At the time, Parrish said: "I'm very happy; things couldn't have worked out better. Getting back home was our top priority as a family. This is where our lives are . . . where we've rooted ourselves."[34]

Parrish was the Angels starting catcher from 1989 to 1991, starting over 100 games at the position each year. In 1990, he regained his offensive power, hitting 24 home runs and winning his sixth and final Silver Slugger Award.[2]

He played two-and-a-half months for the Angeles in 1992, compiling a .229 batting average with four home runs and 11 runs batted in.[2] He was released by the Angels on June 23, 1992. At the time, columnist Mike Downey praised Parrish as "one damn fine guy", "a presence of dignity and civility in a sometimes crass and unpleasant setting", and a player who "belongs on any list of baseball's best 10 catchers ever."[35]

Seattle Mariners (1992)

On June 28, 1992, Parrish signed as a free agent to become a backup to catcher Dave Valle of the Seattle Mariners. Parrish, age 36 at the time, noted: "It's not like everybody was beating down my door, but I still feel I have a lot to offer a team. I have a lot of catching experience and by no means do I feel I'm over the hill offensively."[36] He appeared in 69 games for the Mariners, 34 as a catcher, 16 as a first baseman, and 14 as a designated hitter. Hit tallied 11 doubles and eight home runs in 192 at bats.[2]

Final years (1993–1996)

In January 1993, Parrish signed a minor league contract with the Los Angeles Dodgers and accepted an invitation to spring training.[37] With rookie catcher (and future Hall of Fame inductee) Mike Piazza batting .571 during spring training, the Dodgers released Parrish in late March.[38] He spent part of the 1993 season playing in the Dodges farm system for the Triple-A Albuquerque Dukes.[9]

On May 7, 1993, he signed as a free agent with the Cleveland Indians. He appeared in only 10 games, tallying four hits (including a home run) in 20 at bats. He was released by the Indians on May 30, 1993.[2]

In February 1994, Parrish signed a free-agent contract with the Detroit Tigers.[2] He spent part of the 1994 season playing for the Tigers' Triple-A team, the Toledo Mud Hens.[9] He was purchased by the Pittsburgh Pirates, appeared in 40 games for the Pirates in 1994, 34 as the club's starting catcher, and compiled a .270 batting average with three home runs and 15 runs batted in.[2]

In February 1995, Parrish signed as a free agent with the Kansas City Royals. He was then acquired by the Toronto Blue Jays on April 22, 1995.[2] On May 29, Parrish hit two home runs against the Detroit Tigers.[39] He appeared in 70 games for the Blue Jays, including 49 games as the team's starting catcher. He compiled a .202 batting average with Toronto and hit four home runs with 22 runs batted in. He appeared in his final major-league game on September 23, 1995, at age 39.[2]

Parrish signed as a free agent with the Pittsburgh Pirates in January 1996.[2] He was released by the Pirates in late March. Though one of the coaches typically handled player cuts, manager Jim Leyland personally delivered the news to Parrish. Leyland noted that Parrish had "earned the right to be in a different category."[40]

Career statistics and honors

In a 19-year major-league career, Parrish played in 1,988 games, accumulating 1,782 hits in 7,067 at bats for a .252 career batting average along with 324 home runs and 1,070 runs batted in.[2] Parrish was an eight-time All-Star (1980, 1982–86, 1988, and 1990), and he won three Gold Glove Awards (1983–85).[2][41] Parrish was a six-time winner of the Silver Slugger Award, which is awarded annually to the best offensive player at each position.[42]

Parrish ranks as one of the greatest power-hitting catchers in baseball history. By 1994, he ranked fourth in major-league history in home runs as a catcher, trailing only Hall of Famers Carlton Fisk, Johnny Bench, and Yogi Berra.[43] He now ranks sixth, having been passed by Hall of Famers Mike Piazza and Ivan Rodriguez.[44]

Parrish also ranks as one of the most durable catchers in baseball history. At the time of his retirement, his 1,818 games at the position ranked seventh in baseball history. As of 2022, he ranks 13th.[45]

He led American League catchers twice in baserunners caught stealing, once in assists, and once in caught stealing percentage.[2] Parrish finished second in fielding percentage four times and ended his career with a .991 fielding percentage.[2]

In 2001, Parrish received 9 votes (1.7% of the ballots) for induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.[46] Because he did not receive 5% of the vote, he was not eligible to remain on the following year's ballot. Parrish was inducted into the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame in 2002.[47][48]

Coach, manager, and broadcaster

Kansas City and San Antonio (1996–1997)

In June 1996, Parrish was hired by the Kansas City Royals as a special catching instructor to work with catcher Mike Sweeney.[49] In 1997, he was the hitting coach of the Los Angeles Dodgers Double-A team, the San Antonio Missions.[50][51] He became manager of the San Antonio team in June 1998.[52] San Antonio compiled a 67–73 record with Parrish as its manager.[51]

Detroit (1999–2005)

In October 1998, Parrish was hired as the Detroit Tigers' third base and catching coach. Alan Trammell was hired at the same time as the Tigers' batting coach.[52] He also spent two games as interim manager in July 1999 when regular manager Larry Parrish (no relation) was suspended for bumping an umpire.[53] When Phil Garner took over as manager, Parrish was reassigned as bullpen coach for the 2000 season.[54]

In December 2001, Parrish was hired to served as the color commentator on Detroit Tigers game broadcasts on Detroit's WKBD television station during the 2002 season. He replaced Al Kaline, who had been a Tigers television announcer for 26 years.[55]

In October 2002, Alan Trammell was hired at the Tigers' manager, and Parrish joined Trammell's staff as bullpen coach.[56][57] The Tigers lost 300 games in three years under Trammell, and he was fired at the end of the 2005 season. Parrish was also dismissed at that time.[58]

Ogden (2006)

In January 2006, Parrish was hired by the Los Angeles Dodgers as manager of their rookie-level team, the Ogden Raptors.[59] The team finished with a 37–39 record.[51] He next served as manager of the Great Lakes Loons in Single-A ball during the 2007 season. The team compiled a 57–82 record.[51]

Return to Tigers organization (2014–present)

On February 5, 2014, Parrish was named manager of the Double-A affiliate of the Detroit Tigers, the Erie SeaWolves.[60] He was manager of the SeaWolves for four years from 2014 to 2017, compiling a record there of 329–376.[51]

He later served during the 2018 and 2019 seasons as the manager of Single-A West Michigan Whitecaps of the Midwest League. The Whitecaps compiled a 118–160 record in two seasons under Parrish.[51] In nine seasons as a minor-league manager, Parrish compiled an overall record of 541–657 (.452).[51]

On November 12, 2019, Parrish was named special assistant to the general manager for the Tigers.[61]

Personal life

After the 1978 season, Parrish married Arlyne Nolan, a first runner-up in the Miss California competition.[3] They had three children, David (born 1979), Matthew (born 1982), and Ashley (born 1984).[3] David played baseball at the University of Michigan, was selected by the New York Yankees in the first round of the 2000 amateur draft, and played in the minor leagues from 2000 to 2008.[62][63]

See also

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

References

- ^ George Sipple (April 2, 2007). "Big Wheel keeps turning: Lance Parrish leads Midland's Loons". Detroit Free Press. p. 13C – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an "Lance Parrish". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Mike Lassman. "Lance Parrish". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pete Swanson (June 19, 1977). "Reputation grows: Parrish progress product of work". Evansville Courier and Press. p. 13C – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Lance Parrish must decide on Tiger offer". Progress Bulletin. June 6, 1974. p. 27 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Don Snyder (April 5, 1973). "Top Prep Performer". Los Angeles Times. p. VII-5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Christensen, Espinoza gain Hacienda honors". Progress Bulletin. December 1, 1973. p. 9.

- ^ a b Rick Danis (March 28, 1981). "Potential: Promising Tiger catcher Lance Parrish has bundles of it, waiting to be refined". The Tampa Times. pp. 1C, 6C – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Lance Parrish Minor League Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Bill Madden (March 21, 1978). "Lance Parrish: 'He's gonna be a great one,' says Detroit's Ralph Houk". The Evansville Press. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rebs Agree This One Sweeter". The Montgomery Advertiser. September 9, 1976. p. 41 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1976 Montgomery Rebels". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ Jeff Seidel (June 29, 2021). "Dingler, Greene and Torkelson forming a core that feels like the 'Roar of '84'". Times Herald. p. B1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jim Hawkins (September 2, 1977). "Tigers Add 3 from Farms – Sweet Lou, Al to Follow". Detroit Free Press. p. 1D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Larry Palladino (September 8, 1977). "Rookie Parrish Sparks Nightcap Romp: Tigers Gain Split With Orioles". Ludington Daily News. Associated Press. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Training Camps, A Few To Watch: ance Parrish". Rutland Daily Herald. UPI. March 11, 1979. p. II-6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1979 Detroit Tigers Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ Brian Bragg (July 3, 1980). "Trammell and Parrish All-Stars". Detroit Free Press. p. 1D, 3D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Silver Bat Team Selected". Maryville Journal-Tribune. November 18, 1980. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jim Hawkins (January 8, 1981). "This time, Lance won't let the big dollars get past him". Detroit Free Press. p. 1D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Brian Bragg (January 9, 1981). "Fuming Campbell bares Parrish offer: $375,000 a year". Detroit Free Press. pp. 1D, 6D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Brian Bragg (May 1, 1981). "Parrish becomes the richest Tiger ever". Detroit Free Press. pp. 1F, 3F.

- ^ "Parrish 'can't explain' NL All-Stars' dominance". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. July 15, 1982. p. 7F – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Here Are The Leading Home Run Hitters For Each Position", by Larry F. Rasmussen, Baseball Digest, April 1983, Vol. 42, No. 4, ISSN 0005-609X

- ^ a b Curt Sylvester (October 30, 1982). "Parrish named Tiger of Year". Detroit Free Press. p. 3D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ How Lance Parrish Proved Sparky Anderson Wrong

- ^ Fred Kerber (July 6, 1983). "Parrish-Simmons big debate". New York Daily News. p. 42 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Morris no-hits White Sox". Detroit Free Press. April 8, 1984. p. 1D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "AL all-star voting". Detroit Free Press. July 5, 1984. p. 4D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "How they saw us . . ". Detroit Free Press. October 16, 1984. p. 3D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mitch Albom (January 9, 1987). "Get used to it right now: A proud Tiger is gone". Detroit Free Press. p. 1D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ John Lowe (January 9, 1987). "No miracle: Parrish gone". Detroit Free Press. p. 1D.

- ^ "Whatever happened to ... Lance Parrish". Philadelphia Daily News. December 11, 2002. p. 86 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ John Weyler (October 4, 1988). "Angels Deal for Parrish". Los Angeles Times. pp. III-1, III-5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mike Downey (June 23, 1992). "Lucky Were Fans Who Saw No. 13 Play". Los Angeles Times. p. A9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mariners get what they need, and Parrish gets what he wants". The Sacramento Bee. June 29, 1992 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "People in Sports". News-Pilot. January 9, 1993. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Maryann Hudson (March 23, 1993). "Parrish Gets Word on Catcher Situation". Los Angeles Times. p. C5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Parrish payback: Ex-Tiger hits home for Jays". The Windsor Star. May 30, 1995. p. 1D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Paul Meyer (March 22, 1996). "Parrish's exit opens big door for Osik". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 1B – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ American League Gold Glove Award winners at Baseball-Reference

- ^ Baseball Digest, May 2009, Vol. 68, No. 3, ISSN 0005-609X

- ^ Frank Dolson (March 16, 1994). "Parrish and Tigers: Reunited and it feels so good". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. D2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ivan Rodriguez becomes fifth catcher to reach 300 homers USA Today

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Def. Games as C". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "2001 Hall of Fame Voting". Sports Reference, LLC. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ "Lance Parrish". Michigan Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Mike Brudnell (April 18, 2002). "Parrish, six others enter Hall of Fame". Detroit Free Press. p. 2E – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Veteran help for Sweeney". The Kansas City Star. June 26, 1996. p. D3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Parrish learns different game coaching in the minor leagues". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. August 3, 1997. p. C7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lance Parrish Minor league manager statistics at Baseball Reference

- ^ a b "Former Tigers on staff: Trammell, Parrish hired as assistants". The Windsor Star. October 29, 1998. p. F1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Gene Guidi (July 1, 1999). "AL's Budig: Parrish's appeal denied, but Ausmus' reduced". Detroit Free Press. p. 6G – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ John Lowe (November 3, 1999). "For first time, Tram looks beyond Tigers Garner keeps Parrish to coach in the bullpen". Detroit Free Press. p. 3E – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lance Parrish Takes Tigers' TV Analyst Job". The Windsor Star. December 18, 2001. p. D3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Gene Guidi (October 16, 2002). "He's ba-ack! Gibson new bench coach with Tigers". Detroit Free Press. pp. 1C, 3C – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Gene Guidi (March 31, 2003). "Parrish excited to help Tram". Detroit Free Press – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mitch Albom (October 4, 2005). "3 and out". Detroit Free Press. p. 1E, 10E – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "untitled". Los Angeles Times. January 25, 2006. p. D9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Parrish returns to bench to manage Double-A Erie MLB.com, February 5, 2014

- ^ Beck, Jason (November 12, 2019). "Tigers continue analytics lean with staff moves". MLB.com. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ "Dave Parrish". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ John Lowe (June 21, 2000). "Double play: Lance helps as son signs with Yanks". Detroit Free Press. p. 3D – via Newspapers.com.

External links

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- 1956 births

- Living people

- Albuquerque Dukes players

- American expatriate baseball players in Canada

- American League All-Stars

- Baseball coaches from Pennsylvania

- Baseball players from Pennsylvania

- Bristol Tigers players

- California Angels players

- Cleveland Indians players

- Detroit Tigers announcers

- Detroit Tigers coaches

- Detroit Tigers players

- Evansville Triplets players

- Gold Glove Award winners

- Indios de Mayagüez players

- Lakeland Tigers players

- Major League Baseball bench coaches

- Major League Baseball bullpen coaches

- Major League Baseball catchers

- Major League Baseball third base coaches

- Minor league baseball coaches

- Montgomery Rebels players

- People from Clairton, Pennsylvania

- People from Diamond Bar, California

- Philadelphia Phillies players

- Pittsburgh Pirates players

- San Antonio Missions managers

- Seattle Mariners players

- Silver Slugger Award winners

- Toledo Mud Hens players

- Toronto Blue Jays players