Envoy Extraordinary (novella)

| "Envoy Extraordinary" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by William Golding | |

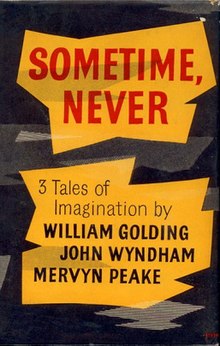

First edition (including the story) | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publication | |

| Published in | Sometime, Never |

| Publication type | Anthology |

| Publisher | Eyre & Spottiswoode |

| Publication date | 1956 |

"Envoy Extraordinary" is a 1956 novella by British writer William Golding, first published by Eyre & Spottiswoode as one third of the collection Sometime, Never, alongside "Consider Her Ways" by John Wyndham and "Boy in Darkness" by Mervyn Peake.[1][2] It was later published in 1971 as the second of three novellas in Golding's collection The Scorpion God.

The story concerns an inventor who anachronistically brings the steam engine to ancient Rome, along with three of the Four Great Inventions of China (gunpowder, the compass, and the printing press).[3]

Golding later adapted "Envoy Extraordinary" into a play called The Brass Butterfly, first performed in Oxford in 1958 starring Alistair Sim and George Cole.

Leighton Hodson compares it to "The Rewards of Industry" from Richard Garnett's 1888 collection The Twilight of the Gods and Other Tales, in which three Chinese brothers bring printing, gunpowder and chess to the West, but only chess is accepted.[4]

Plot

A Greek librarian's assistant named Phanocles and his sister Euphrosyne arrive at the villa of the Roman Emperor, having been forced out of their previous life of because of Phanocles' inventions, which drew scorn and allegations of black magic. Phanocles shows the Emperor a model of his design for a steam-powered warship. The Emperor has no interest in it, but is delighted by the potential of the steam pressure cooker, which Phanocles learned of from a tribe "beyond Syria". Mamillius, the Emperor's grandson, has no interest in either but falls in love with the veiled Euphrosyne when he sees her eyes. Phanocles is given the funds to build his warship, which is named Amphitrite, and a second invention – a gunpowder artillery weapon later called the tormentum – in exchange for building the pressure cooker.

The first version of pressure cooker goes wrong, killing three cooks and destroying the north wing of the villa. Meanwhile, word of Amphitrite's construction reaches the Emperor's heir-designate, Posthumus (see Postumus (praenomen)), who wrongly sees it as part of an attempt to put Mamillius in his stead. He leaves the war he was fighting to return to the villa and force the matter. On the day of Amphitrite's demonstration voyage, Mamillius and Phanocles are nearly killed and the ship's engine, called Talos, is sabotaged, destroying several of the returning Posthumus's warships and most of the harbour through fire. It is revealed that the assassination attempt and sabotage were the work of enslaved rowers worried that the steam engine would make them redundant. The military have similar concerns about the impact of gunpowder on warfare.

In the final section, Mamillius has become heir. Over steam-cooked trout, the Emperor tells Phanocles that he has decided to marry Euphrosyne himself to avoid embarrassing Mamillius, as he has deduced that the reason she never takes off her veil is that she has a hare lip. Phanocles talks to the Emperor about his idea for a compass to solve the issue of navigating without the wind and reveals his final invention: the printing press. The Emperor is initially excited but becomes terrified by the prospect of vast amounts of bad writing that he would be obliged to read. To be rid of Phanocles and his dangerous ideas, he makes him Envoy Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to China.

The Brass Butterfly

Golding adapted "Envoy Extraordinary" into a radio play for the BBC and then into a play called The Brass Butterfly in 1957.[1][5][6] Changes to the story included writing out Euphrosyne's hare lip and making her a Christian, with Mamillius converting to Christianity and marrying her at the end.[2] The play also makes concrete the setting of the story as 3rd century Capri; this was left unstated in the novella.[1][7]

The play, which starred Alistair Sim (who had commissioned the script and also directed[5]) as the Emperor opposite George Cole as Phanocles, opened at the New Theatre Oxford on 24 February 1958 and moved to the Strand Theatre in the West End in April by way of a brief tour through Liverpool, Leeds, Newcastle, Glasgow and Manchester. Although there had been some excitement about it in Oxford, it was not particularly well received in London where it lasted for one month. After its first night at the Strand on 17 April 1958, critics made much of a number of boos mixed in with the applause, calling the play "slack" and "lukewarm", though the Sim's performance did receive praise.[2][8]

The script of the play was published in the UK on 4 July 1958 in an edition of 3,000 copies that was dedicated "To Alistair Sim, in gratitude and affection", and in the US in 1964.[6]

In 1967 The Brass Butterfly was filmed for the Australian TV series Love and War.[9]

Its first American production was in 1970 at the Chelsea Theater Center, starring Paxton Whitehead as the Emperor and Sam Waterston as Phanocles. Reviewing that production, critic Clive Barnes of The New York Times called the play "sub-Shavian and aimless". He maintained that opinion when reviewing a 1973 production on the second night of the Shaw Festival in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario that starred Lockwood West and James Valentine, adding that while the premise was appealing and some of the jokes funny, nevertheless "Mr. Golding at his best does sound terribly like Mr. Shaw at his worst".[10]

Walter Sullivan writing for The Sewanee Review in 1963, described The Brass Butterfly as "witty but by no means profound" and "Envoy Extraordinary" as "a not very successful novella about ancient Rome".[11] In his book about Golding, Kevin McCarron says that The Brass Butterfly is "too often dismissed as lightweight" and that it has more to say about "the terrible cost of progress" than it is given credit for.[5]

References

- ^ a b c Clute, John (16 January 2021). "Golding, William". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Carey, John (2012). "Chapter 15. The Brass Butterfly". William Golding: The Man who Wrote Lord of the Flies. Free Press. pp. 206–212. ISBN 978-1-4391-8732-6.

- ^ Prusse, Michael C. (2007). "Golding, William (19 September 1911 - 19 June 1993)". In Bruccoli, Matthew J.; Layman, Richard (eds.). Nobel Prize Laureates in Literature, Part 2: Faulkner-Kipling. Dictionary of Literary Biography. Vol. 331. Thomson Gale. Retrieved 24 April 2021 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Hodson, Leighton (1978). "The Scorpion God: Clarity, Technique and Communication". In Biles, Jack I.; Evans, Robert O. (eds.). William Golding: Some Critical Considerations. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 188–202. ISBN 978-0-8131-6212-6. JSTOR j.ctt130j3cq.

- ^ a b c McCarron, Kevin (2006). William Golding. Oxford University Press. pp. 25–29. ISBN 978-0-7463-1143-1.

- ^ a b Gekoski, R. A.; Grogan, P. A. (1994). William Golding A Bibliography 1934-1993. London: André Deutsch. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-233-98611-1. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Lane, Denis; Stein, Rita (eds.). "Golding, William (1911- )". Modern British Literature. A Library of Literary Criticism. Vol. V. Second Supplement. Frederick Ungar. pp. 174–176. ISBN 0-8044-3140-X.

- ^ Crompton, Don (1985). "The Scorpion God (1971)". A View from the Spire: William Golding's Later Novels. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 73–93. ISBN 0-631-13826-9. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ "Television". The Sydney Morning Herald. 25 September 1967. p. 13. JSTOR 27540940. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Barnes, Clive (23 June 1973). "Stage: 'Brass Butterfly'". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Walter (1963). "William Golding: The Fables and the Art". The Sewanee Review. 71 (4): 660–664. JSTOR 27540940.

Further reading

- Pawlicki, Marek (2016). "Memory performance in William Golding's "Envoy Extraordinary"". Crossroads: A Journal of English Studies (15 (4/2016)). The University of Bialystok: 19–29. doi:10.15290/cr.2016.15.4.02.