Temple of the Gadde

The Temple of the Gadde is a temple in the modern-day Syrian city of Dura-Europos, located near the agora (insula H1). It contains reliefs dedicated to the protective deities (in Aramaic, Gaddē) of Dura-Europos and the nearby city of Palmyra, after whom the temple was named by its excavators. The temple was excavated between 1934 and January 1936 by the French/American expedition of Yale University, led by Michael Rostovtzeff.[1]

Description

The city of Palmyra (also known as Tadmor, in Semitic languages) is located about 220 kilometers west of Dura-Europos. The oasis city flourished due to its participation in caravan trade.[4] The presence of Palmyrenes in Dura-Europos is attested from 33 BCE onwards, where they lived as merchants or soldiers hired by the Roman army for their expert archery.[5] Based on surviving text, the Temple of the Gadde was built by and for Palmyrenes living in or visiting Dura-Europos.[4]

The age of the temple complex is unknown. According to the preliminary excavation report, the temple was repeatedly expanded and rebuilt over time. In total, four phases of construction can be discerned. The final phase (IV) is dated to 159 CE, since two relief sculptures have inscriptions dating them to this year. Phase III likely ended around 150 CE. The two earlier phases (II & I) must have fallen in the previous century, but the exact dates are not known. After 159 CE, the temple experienced no further noteworthy additions. Numerous small altars were set up in the temple as well as a platform at the main entrance.[6]

The temple complex takes up much of the eastern section of insula H1. It measures about 42 meters north-south and 22 meters east-west. It has two parts, each accessed from the road to the east. The southern part of the temple contains the main courtyard and chief sanctuary. In the north, there is a second courtyard with various adjoining rooms. A propylon leads into the southern courtyard, on the opposite side of which there is a pronaos and cella (Naos 3) with further rooms. The pronaos is 11.05 m wide and 5.1 m deep. The interior room was originally about 8 m high and decorated with wall paintings, which only survive in tiny fragments. The cella is 4.48 m wide and 4.12 m deep. The cella contained three niches on the western side (opposite the entrance). One part of the room was decorated solely with figural wall paintings, but little of the painting survives. To the north of the pronaos was a hall with several rows of benches (known as a salle à gradins).[6][7] Through this hall was the north courtyard, which contained another cella. A foundation deposit was found beneath the sanctuary, consisting of 21 amulets.[8]

The temple contained a large number of graffiti, in Palmyrene, Greek, and Latin.[9]

Relief sculpture

The modern name of the temple derives from two dedicatory reliefs, which were found in the temple, in the main cella (Naos 3). These reliefs were originally located on the side walls of the cella, so they do not actually depict the primary god of the sanctuary, which was probably Malakbel.[10] Both reliefs are made of limestone, most likely of Palmyrene origin.[11]

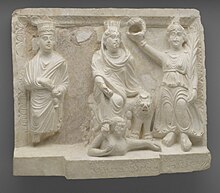

One of them shows the female protective deity of Palmyra in a guise modelled on the Tyche of Antioch. She sits between two figures, wearing a mural crown and Greek clothing. On her left is the dedicator of the relief, depicted as a priest, and on her right a Nike. A dedicatory inscription in the Palmyrene language says: "The Gad of Palmyra, made by Hairan bar Mailwa bar Nasor."[12] A second inscription gives a date, "in the month of Nisan, year 470 [= AD 159]."[13]

On the other relief, by contrast, there is the male protective deity of Dura-Europos. He is bearded and wears a tunic. He very closely resembles Zeus Megistos. At his right is Seleucus Nicator, as the Palmyrene inscription indicates,[14] and on the left is the dedicator of the relief. Dura Europus was founded in the reign of Seleucus (311-280 BC), so even several centuries later he was the object of special veneration in the city. The relief is probably the product of a Palmyrene workshop.[15] It was dedicated by the same donor in the same year as the first relief. The dedicatory inscription states: "The god, Gad of Dura; made by Hairan bar Maliku Nasor, in the month of Nisan, year 470 [AD 159]."[16]

The cella also contained a relief that depicted the Semitic god Iarhibol. An inscription records "Bani Mitha, the archers" as the donors.[17]

References

- ^ Rostovtzeff, M.I.; Brown, F.E.; Welles, C.B. (1939). The excavations at Dura-Europos: Preliminary Report of Seventh and Eighth Season of Work 1933–1934 and 1934–1935. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ Dura-Europos : crossroads of antiquity. Lisa R. Brody, Gail L. Hoffman, McMullen Museum of Art, Yale University. Art Gallery. Chestnut Hill, Mass.: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College. 2011. ISBN 978-1-892850-16-4. OCLC 670480460.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Kropp 2013, p. 225.

- ^ a b Dirven, Lucinda (2011). "Strangers and Sojourners: the religious behavior of Palmyrenes and other foreigners in Dura Europos". Dura-Europos : crossroads of antiquity. Lisa R. Brody, Gail L. Hoffman, McMullen Museum of Art, Yale University. Art Gallery. Chestnut Hill, Mass.: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College. ISBN 978-1-892850-16-4. OCLC 670480460.

- ^ Dirven, Lucinda (1999). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos : a study of religious interaction in Roman Syria. Boston: Brill. p. 304. ISBN 90-04-11589-7. OCLC 42296260.

- ^ a b M. I. Rostovtzeff, F. E. Brown, C. B. Welles: The excavations at Dura-Europos: Preliminary Report of Seventh and Eighth Season of Work 1933–1934 and 1934–1935. Yale University Press, New Haven u. a. 1939, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Baird, Jennifer (2018). Dura-Europos. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 104. ISBN 9781472522115.

- ^ Baird, Jennifer (2018). Dura-Europos. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 99. ISBN 9781472522115.

- ^ Baird, Jennifer (2018). Dura-Europos. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 74. ISBN 9781472522115.

- ^ Baird, Jennifer (2018). Dura-Europos. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 24. ISBN 9781472522115.

- ^ BRODY, LISA R.; SNOW, CAROL E. (2019). "Quarries at the Crossroads: Sourcing Limestone Sculpture from Dura-Europos and Palmyra at Yale". Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin: 78–85. ISSN 0084-3539.

- ^ Delbert R. Hillers, Eleonora Cussini: Palmyrene Aramaic texts. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1996, ISBN 0-8018-5278-1, p. 172, no. 1097 (Doura 31).

- ^ M. I. Rostovtzeff, F. E. Brown, C. B. Welles: The excavations at Dura-Europos: Preliminary Report of Seventh and Eighth Season of Work 1933–1934 and 1934–1935. Yale University Press, New Haven 1939, pp. 278–279; Delbert R. Hillers, Eleonora Cussini: Palmyrene Aramaic texts. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1996, ISBN 0-8018-5278-1, p. 172, no. 1094 (Doura 28).

- ^ Delbert R. Hillers, Eleonora Cussini: Palmyrene Aramaic texts. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1996, ISBN 0-8018-5278-1, p. 172, no. 1095 (Doura 29).

- ^ M. I. Rostovtzeff, F. E. Brown, C. B. Welles: The excavations at Dura-Europos: Preliminary Report of Seventh and Eighth Season of Work 1933–1934 and 1934–1935. Yale University Press, New Haven 1939, pp. 258–262, Table XXXIII.

- ^ M. I. Rostovtzeff, F. E. Brown, C. B. Welles: The excavations at Dura-Europos: Preliminary Report of Seventh and Eighth Season of Work 1933–1934 and 1934–1935. Yale University Press, New Haven 1939, pp. 277–278.

- ^ M. I. Rostovtzeff, F. E. Brown, C. B. Welles: The excavations at Dura-Europos: Preliminary Report of Seventh and Eighth Season of Work 1933–1934 and 1934–1935. Yale University Press, New Haven 1939, pp. 279–280.

Sources

- Kropp, Andreas J. M. (2013). Images and Monuments of Near Eastern Dynasts, 100 BC – AD 100. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967072-7.

- M. I. Rostovtzeff, F. E. Brown, C. B. Welles: The excavations at Dura-Europos: Preliminary Report of Seventh and Eighth Season of Work 1933–1934 and 1934–1935. Yale University Press, New Haven 1939, pp. 218–283.

- Delbert R. Hillers, Eleonora Cussini: Palmyrene Aramaic texts. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1996, ISBN 0-8018-5278-1, S. 172–173, Nummer 1094–1100 (Doura 28–34).