Timeline of cosmological theories

Appearance

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

This timeline of cosmological theories and discoveries is a chronological record of the development of humanity's understanding of the cosmos over the last two-plus millennia. Modern cosmological ideas follow the development of the scientific discipline of physical cosmology.

Pre-1900

- c. 16th century BCE – Mesopotamian cosmology has a flat, circular Earth enclosed in a cosmic ocean.[1]

- c. 15th–11th century BCE – The Rigveda of Hinduism has some cosmological hymns, particularly in the late book 10, notably the Nasadiya Sukta which describes the origin of the universe, originating from the monistic Hiranyagarbha or "Golden Egg". Primal matter remains manifest for 311.04 trillion years and unmanifest for an equal length. The universe remains manifest for 4.32 billion years and unmanifest for an equal length. Innumerable universes exist simultaneously. These cycles have and will last forever, driven by desires.

- 6th century BCE – The Babylonian Map of the World shows the Earth surrounded by the cosmic ocean, with seven islands arranged around it so as to form a seven-pointed star. Contemporary Biblical cosmology reflects the same view of a flat, circular Earth swimming on water and overarched by the solid vault of the firmament to which are fastened the stars.

- 6th–4th century BCE – Greek philosophers, as early as Anaximander,[2] introduce the idea of multiple or even infinite universes.[3] Democritus further detailed that these worlds varied in distance, size; the presence, number and size of their suns and moons; and that they are subject to destructive collisions.[4] Also during this time period, the Greeks established that the earth is spherical rather than flat.[5][6]

- 4th century BCE – Aristotle proposes an Earth-centered universe in which the Earth is stationary and the cosmos (or universe) is finite in extent but infinite in time. However, others like Philolaus and Hicetas rejected geocentrism.[7] Plato seems to have argued that the universe did have a beginning, but Aristotle and others interpreted his words differently.[8]

- 4th century BCE – De Mundo – Five elements, situated in spheres in five regions, the less being in each case surrounded by the greater – namely, earth surrounded by water, water by air, air by fire, and fire by ether – make up the whole Universe.[9]

- 3rd century BCE – Aristarchus of Samos proposes a Sun-centered universe and Earth's rotation in its own axis. He also provides evidences for his theory from his own observations.[10]

- 3rd century BCE – Archimedes in his essay The Sand Reckoner, estimates the diameter of the cosmos to be the equivalent in stadia of what would in modern times be called two light years

- 2nd century BCE – Seleucus of Seleucia elaborates on Aristarchus' heliocentric universe, using the phenomenon of tides to explain heliocentrism. Seleucus was the first to prove the heliocentric system through reasoning. Seleucus' arguments for a heliocentric cosmology were probably related to the phenomenon of tides. According to Strabo (1.1.9), Seleucus was the first to state that the tides are due to the attraction of the Moon, and that the height of the tides depends on the Moon's position relative to the Sun. Alternatively, he may have proved heliocentricity by determining the constants of a geometric model for it.[11]

- 2nd century CE-5th century CE – Jain cosmology considers the loka, or universe, as an uncreated entity, existing since infinity, the shape of the universe as similar to a man standing with legs apart and arm resting on his waist. This Universe, according to Jainism, is broad at the top, narrow at the middle and once again becomes broad at the bottom.

- c. 2nd century BCE–3rd century CE – In Hindu cosmology, the Manusmriti (1.67–80) and Puranas describe time as cyclical, with a new universe (planets and life) created by Brahma every 8.64 billion years. The universe is created, maintained, and destroyed within a kalpa (day of Brahma) period lasting for 4.32 billion years, and is followed by a pralaya (night) period of partial dissolution equal in duration. In some Puranas (e.g. Bhagavata Purana), a larger cycle of time is described where matter (mahat-tattva or universal womb) is created from primal matter (prakriti) and root matter (pradhana) every 622.08 trillion years, from which Brahma is born.[12] The elements of the universe are created, used by Brahma, and fully dissolved within a maha-kalpa (life of Brahma; 100 of his 360-day years) period lasting for 311.04 trillion years containing 36,000 kalpas (days) and pralayas (nights), and is followed by a maha-pralaya period of full dissolution equal in duration.[13][14][15][16] The texts also speak of innumerable worlds or universes.[17]

- 2nd century CE – Ptolemy proposes an Earth-centered universe, with the Sun, Moon, and visible planets revolving around the Earth. He also calculates the positions, orbits and positional equations of the Heavenly bodies along with instruments to measure these quantities in his book The Almagest. His book also cataloged 1022 stars and other astronomical objects which remained the largest astronomical catalogue until the 17th century AD.[18][19]

- 5th century (or earlier) – Buddhist texts speak of "hundreds of thousands of billions, countlessly, innumerably, boundlessly, incomparably, incalculably, unspeakably, inconceivably, immeasurably, inexplicably many worlds" to the east, and "infinite worlds in the ten directions".[20][21]

- 5th century – Several Indian astronomers propose a rudimentary Sun-centered universe, including Aryabhata. He also writes a treatise on motion of planets, sun and moon and stars.Aryabhatta puts forward the theory of rotation of the earth in its own axis and explained day and night was caused by the diurnal rotation of the earth. He also provided empirical evidence for his notion from his astronomical experiments and observation.[22]

- 5th century – The Jewish talmud gives an argument for finite universe theory along with explanation.

- 6th century – John Philoponus proposes a universe that is finite in time and argues against the ancient Greek notion of an infinite universe

- 7th century – The Quran says in Chapter 21: Verse 30 – "Have those who disbelieved not considered that the heavens and the earth were a joined entity, and We separated them".

- 9th–12th centuries – Al-Kindi (Alkindus), Saadia Gaon (Saadia ben Joseph) and Al-Ghazali (Algazel) support a universe that has a finite past and develop two logical arguments for the notion.

- 12th century – Fakhr al-Din al-Razi discusses Islamic cosmology, rejects Aristotle's idea of an Earth-centered universe, and, in the context of his commentary on the Quranic verse, "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds," and proposes that the universe has more than "a thousand worlds beyond this world."[23]

- 14th century – Christian scholar Nicholas of Cusa and proposed that the Earth rotates on its axis in his book, On Learned Ignorance (1440).[24]

- 14th century – Several European mathematicians and astronomers develop the theory of Earth's rotation including Nicole Oresme. Nicole Oresme also give logical reasoning. empirical evidence and mathematical proofs for his notion.[25][26]

- 15th–16th centuries – Nilakantha Somayaji and Tycho Brahe propose a universe in which the planets orbit the Sun and the Sun orbits the Earth, known as the Tychonic system

- 1543 – Nicolaus Copernicus publishes his heliocentric universe in his De revolutionibus orbium coelestium.[27]

- 1576 – Thomas Digges modifies the Copernican system by removing its outer edge and replacing the edge with a star-filled unbounded space

- 1584 – Giordano Bruno proposes a non-hierarchical cosmology, wherein the Copernican Solar System is not the center of the universe, but rather, a relatively insignificant star system, amongst an infinite multitude of others

- 1610 – Johannes Kepler uses the dark night sky to argue for a finite universe

- 1687 – Sir Isaac Newton's laws describe large-scale motion throughout the universe

- 1720 – Edmund Halley puts forth an early form of Olbers' paradox

- 1729 – James Bradley discovers the aberration of light, due to the Earth's motion around the Sun.

- 1744 – Jean-Philippe de Cheseaux puts forth an early form of Olbers' paradox

- 1755 – Immanuel Kant asserts that the nebulae are really galaxies separate from, independent of, and outside the Milky Way Galaxy; he calls them island universes.

- 1785 – William Herschel proposes a heliocentric model of the universe that Earth's Sun is at or near the center of the universe, which at the time was assumed to only be the Milky Way Galaxy.[28]

- 1791 – Erasmus Darwin pens the first description of a cyclical expanding and contracting universe in his poem The Economy of Vegetation

- 1826 – Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers puts forth Olbers' paradox

- 1837 – Following over 100 years of unsuccessful attempts, Friedrich Bessel, Thomas Henderson and Otto Struve measure the parallax of a few nearby stars; this is the first measurement of any distances outside the Solar System.

- 1848 – Edgar Allan Poe offers first correct solution to Olbers' paradox in Eureka: A Prose Poem, an essay that also suggests the expansion and collapse of the universe

- 1860s – William Huggins develops astronomical spectroscopy; he shows that the Orion nebula is mostly made of gas, while the Andromeda nebula (later called Andromeda Galaxy) is probably dominated by stars.

1900–1949

- 1905 – Albert Einstein publishes the Special Theory of Relativity, positing that space and time are not separate continua

- 1912 – Henrietta Leavitt discovers the period-luminosity law for Cepheid variable stars, which becomes a crucial step in measuring distances to other galaxies.

- 1915 – Albert Einstein publishes the General Theory of Relativity, showing that an energy density warps spacetime

- 1917 – Willem de Sitter derives an isotropic static cosmology with a cosmological constant, as well as an empty expanding cosmology with a cosmological constant, termed a de Sitter universe

- 1918 – Harlow Shapley's work on globular clusters showed that the heliocentrism model of cosmology was wrong, and galactocentrism replaced heliocentrism as the dominant model of cosmology.[28]

- 1920 – The Shapley-Curtis Debate, on the distances to spiral nebulae, takes place at the Smithsonian

- 1921 – The National Research Council (NRC) published the official transcript of the Shapley-Curtis Debate

- 1922 – Vesto Slipher summarizes his findings on the spiral nebulae's systematic redshifts

- 1922 – Alexander Friedmann finds a solution to the Einstein field equations which suggests a general expansion of space

- 1923 – Edwin Hubble measures distances to a few nearby spiral nebulae (galaxies), the Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Triangulum Galaxy (M33), and NGC 6822. The distances place them far outside the Milky Way, and implies that fainter galaxies are much more distant, and the universe is composed of many thousands of galaxies.

- 1927 – Georges Lemaître discusses the creation event of an expanding universe governed by the Einstein field equations. From its solutions to the Einstein equations, he predicts the distance-redshift relation.

- 1928 – Howard P. Robertson briefly mentions that Vesto Slipher's redshift measurements combined with brightness measurements of the same galaxies indicate a redshift-distance relation

- 1929 – Edwin Hubble demonstrates the linear redshift-distance relation and thus shows the expansion of the universe

- 1933 – Edward Milne names and formalizes the cosmological principle

- 1933 – Fritz Zwicky shows that the Coma cluster of galaxies contains large amounts of dark matter. This result agrees with modern measurements, but is generally ignored until the 1970s.

- 1934 – Georges Lemaître interprets the cosmological constant as due to a vacuum energy with an unusual perfect fluid equation of state

- 1938 – Paul Dirac suggests the large numbers hypothesis, that the gravitational constant may be small because it is decreasing slowly with time

- 1948 – Ralph Alpher, Hans Bethe ("in absentia"), and George Gamow examine element synthesis in a rapidly expanding and cooling universe, and suggest that the elements were produced by rapid neutron capture

- 1948 – Hermann Bondi, Thomas Gold, and Fred Hoyle propose steady state cosmologies based on the perfect cosmological principle

- 1948 – George Gamow predicts the existence of the cosmic microwave background radiation by considering the behavior of primordial radiation in an expanding universe

1950–1999

- 1950 – Fred Hoyle coins the term "Big Bang", saying that it was not derisive; it was just a striking image meant to highlight the difference between that and the Steady-State model.

- 1961 – Robert Dicke argues that carbon-based life can only arise when the gravitational force is small, because this is when burning stars exist; first use of the weak anthropic principle

- 1963 – Maarten Schmidt discovers the first quasar; these soon provide a probe of the universe back to substantial redshifts.

- 1965 – Hannes Alfvén proposes the now-discounted concept of ambiplasma to explain baryon asymmetry and supports the idea of an infinite universe.

- 1965 – Martin Rees and Dennis Sciama analyze quasar source count data and discover that the quasar density increases with redshift.

- 1965 – Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, astronomers at Bell Labs discover the 2.7 K microwave background radiation, which earns them the 1978 Nobel Prize in Physics. Robert Dicke, James Peebles, Peter Roll and David Todd Wilkinson interpret it as a relic from the big bang.

- 1966 – Stephen Hawking and George Ellis show that any plausible general relativistic cosmology is singular

- 1966 – James Peebles shows that the hot Big Bang predicts the correct helium abundance

- 1967 – Andrei Sakharov presents the requirements for baryogenesis, a baryon-antibaryon asymmetry in the universe

- 1967 – John Bahcall, Wal Sargent, and Maarten Schmidt measure the fine-structure splitting of spectral lines in 3C191 and thereby show that the fine-structure constant does not vary significantly with time

- 1967 – Robert Wagner, William Fowler, and Fred Hoyle show that the hot Big Bang predicts the correct deuterium and lithium abundances

- 1968 – Brandon Carter speculates that perhaps the fundamental constants of nature must lie within a restricted range to allow the emergence of life; first use of the strong anthropic principle

- 1969 – Charles Misner formally presents the Big Bang horizon problem

- 1969 – Robert Dicke formally presents the Big Bang flatness problem

- 1970 – Vera Rubin and Kent Ford measure spiral galaxy rotation curves at large radii, showing evidence for substantial amounts of dark matter.

- 1973 – Edward Tryon proposes that the universe may be a large scale quantum mechanical vacuum fluctuation where positive mass-energy is balanced by negative gravitational potential energy

- 1976 – Alex Shlyakhter uses samarium ratios from the Oklo prehistoric natural nuclear fission reactor in Gabon to show that some laws of physics have remained unchanged for over two billion years

- 1977 – Gary Steigman, David Schramm, and James Gunn examine the relation between the primordial helium abundance and number of neutrinos and claim that at most five lepton families can exist.

- 1980 – Alan Guth and Alexei Starobinsky independently propose the inflationary Big Bang universe as a possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems.

- 1981 – Viatcheslav Mukhanov and G. Chibisov propose that quantum fluctuations could lead to large scale structure in an inflationary universe.

- 1982 – The first CfA galaxy redshift survey is completed.

- 1982 – Several groups including James Peebles, J. Richard Bond and George Blumenthal propose that the universe is dominated by cold dark matter.

- 1983–1987 – The first large computer simulations of cosmic structure formation are run by Davis, Efstathiou, Frenk and White. The results show that cold dark matter produces a reasonable match to observations, but hot dark matter does not.

- 1988 – The CfA2 Great Wall is discovered in the CfA2 redshift survey.

- 1988 – Measurements of galaxy large-scale flows provide evidence for the Great Attractor.

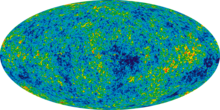

- 1990 – Preliminary results from NASA's COBE mission confirm the cosmic microwave background radiation has a blackbody spectrum to an astonishing one part in 105 precision, thus eliminating the possibility of an integrated starlight model proposed for the background by steady state enthusiasts.

- 1992 – Further COBE measurements discover the very small anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background, providing a "baby picture" of the seeds of large-scale structure when the universe was around 1/1100th of its present size and 380,000 years old.

- 1996 – The first Hubble Deep Field is released, providing a clear view of very distant galaxies when the universe was around one-third of its present age.

- 1998 – Controversial evidence for the fine-structure constant varying over the lifetime of the universe is first published.

- 1998 – The Supernova Cosmology Project and High-Z Supernova Search Team discover cosmic acceleration based on distances to Type Ia supernovae, providing the first direct evidence for a non-zero cosmological constant.

- 1999 – Measurements of the cosmic microwave background radiation with finer resolution than COBE, (most notably by the BOOMERanG experiment see Mauskopf et al., 1999, Melchiorri et al., 1999, de Bernardis et al. 2000) provide evidence for oscillations (the first acoustic peak) in the anisotropy angular spectrum, as expected in the standard model of cosmological structure formation. The angular position of this peak indicates that the geometry of the universe is close to flat.

Since 2000

- 2001 – The 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey (2dF) by an Australian/British team gave strong evidence that the matter density is near 25% of critical density. Together with the CMB results for a flat universe, this provides independent evidence for a cosmological constant or similar dark energy.

- 2002 – The Cosmic Background Imager (CBI) in Chile obtained images of the cosmic microwave background radiation with the highest angular resolution of 4 arc minutes. It also obtained the anisotropy spectrum at high-resolution not covered before up to l ~ 3000. It found a slight excess in power at high-resolution (l > 2500) not yet completely explained, the so-called "CBI-excess".

- 2003 – NASA's Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) obtained full-sky detailed pictures of the cosmic microwave background radiation. The images can be interpreted to indicate that the universe is 13.7 billion years old (within one percent error), and are very consistent with the Lambda-CDM model and the density fluctuations predicted by inflation.

- 2003 – The Sloan Great Wall is discovered.

- 2004 – The Degree Angular Scale Interferometer (DASI) first obtained the E-mode polarization spectrum of the cosmic microwave background radiation.

- 2005 – The Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and 2dF redshift surveys both detected the baryon acoustic oscillation feature in the galaxy distribution, a key prediction of cold dark matter models.

- 2006 – Three-year WMAP results are released, confirming previous analysis, correcting several points, and including polarization data.

- 2009–2013 – Planck, a space observatory operated by the European Space Agency (ESA), mapped the anisotropies of the cosmic microwave background radiation, with increased sensitivity and small angular resolution.

- 2006–2011 – Improved measurements from WMAP, new supernova surveys ESSENCE and SNLS, and baryon acoustic oscillations from SDSS and WiggleZ, continue to be consistent with the standard Lambda-CDM model.

- 2014 – Astrophysicists of the BICEP2 collaboration announce the detection of inflationary gravitational waves in the B-mode power spectrum, which if confirmed, would provide clear experimental evidence for the theory of inflation.[29][30][31][32][33][34] However, in June lowered confidence in confirming the cosmic inflation findings was reported.[33][35][36]

- 2016 – LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration announce that gravitational waves were directly detected by two LIGO detectors. The waveform matched the prediction of General relativity for a gravitational wave emanating from the inward spiral and merger of a pair of black holes of around 36 and 29 solar masses and the subsequent "ringdown" of the single resulting black hole.[37][38][39] The second detection verified that GW150914 is not a fluke, thus opens entire new branch in astrophysics, gravitational-wave astronomy.[40][41]

- 2019 – The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration publishes the image of the black hole at the center of the M87 Galaxy.[42] This is the first time astronomers have ever captured an image of a black hole, which once again proves the existence of black holes and thus helps verify Einstein's general theory of relativity.[43] This was done by utilising very-long-baseline interferometry.[44]

- 2020 — Physicist Lucas Lombriser of the University of Geneva presents a possible way of reconciling the two significantly different determinations of the Hubble constant by proposing the notion of a surrounding vast "bubble", 250 million light years in diameter, that is half the density of the rest of the universe.[45][46]

- 2020 — Scientists publish a study which suggests that the Universe is no longer expanding at the same rate in all directions and that therefore the widely accepted isotropy hypothesis might be wrong. While previous studies already suggested this, the study is the first to examine galaxy clusters in X-rays and, according to Norbert Schartel, has a much greater significance. The study found a consistent and strong directional behavior of deviations – which have earlier been described to indicate a "crisis of cosmology" by others – of the normalization parameter A, or the Hubble constant H0. Beyond the potential cosmological implications, it shows that studies which assume perfect isotropy in the properties of galaxy clusters and their scaling relations can produce strongly biased results.[47][48][49][50][51]

- 2020 — Scientists report verifying measurements 2011–2014 via ULAS J1120+0641 of what seem to be a spatial variation in four measurements of the fine-structure constant, a basic physical constant used to measure electromagnetism between charged particles, which indicates that there might be directionality with varying natural constants in the Universe which would have implications for theories on the emergence of habitability of the Universe and be at odds with the widely accepted theory of constant natural laws and the standard model of cosmology which is based on an isotropic Universe.[52][53][54][55]

See also

Physical cosmology

- Chronology of the universe

- List of cosmologists

- Interpretations of quantum mechanics

- Non-standard cosmology

- Timeline of knowledge about galaxies, clusters of galaxies, and large-scale structure

Belief systems

Others

References

- ^ Horowitz (1998), p. xii

- ^ This is a matter of debate:

- Cornford, F. M. (1934). "Innumerable Worlds in Presocratic Philosophy". The Classical Quarterly. 28 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1017/S0009838800009897. ISSN 1471-6844. S2CID 170168443.

- Curd, Patricia; Graham, Daniel W. (2008). The Oxford Handbook of Presocratic Philosophy. Oxford University Press. pp. 239–41. ISBN 978-0-19-972244-0.

- Gregory, Andrew (2016). "7 Anaximander: One Cosmos or Many?". Anaximander: A Re-assessment. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 121–142. ISBN 978-1472506252.

- ^

- Siegfried, Tom. "Long Live the Multiverse!". Scientific American.

- Siegfried, Tom (2019). "Aristotle versus the Atomists". The number of the heavens : a history of the multiverse and the quest to understand the cosmos. Harvard. ISBN 978-0674975880.

- ^ "there are innumerable worlds of different sizes. In some there is neither sun nor moon, in others they are larger than in ours and others have more than one. These worlds are at irregular distances, more in one direction and less in another, and some are flourishing, others declining. Here they come into being, there they die, and they are destroyed by collision with one another. Some of the worlds have no animal or vegetable life nor any water."

- Guthrie, W. K. C.; Guthrie, William Keith Chambers (1962). A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 2, The Presocratic Tradition from Parmenides to Democritus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 404–06. ISBN 978-0-521-29421-8.

- Vamvacas, Constantine J. (2009). The Founders of Western Thought – The Presocratics: A diachronic parallelism between Presocratic Thought and Philosophy and the Natural Sciences. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 219–20. ISBN 978-1-4020-9791-1.

- ^ "Ancient Greek Astronomy and Cosmology | Modeling the Cosmos | Articles and Essays | Finding Our Place in the Cosmos: From Galileo to Sagan and Beyond | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Washington, DC.

- ^ Blakemore, Erin. "Christopher Columbus Never Set Out to Prove the Earth was Round". History.com.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (2019). "heliocentrism | Definition, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Sorabji, Richard (2005). The Philosophy of the Commentators, 200–600 AD: Physics. Cornell University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-8014-8988-4.

- ^ Aristotle; Forster, E. S. (Edward Seymour); Dobson, J. F. (John Frederic) (1914). De Mundo. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. p. 2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ D., J. L. E. (July 1913). "Aristarchus of Samos: The Ancient Copernicus". Nature. 91 (2281): 499–500. doi:10.1038/091499a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ "Aristarchus of Samos (310-230 BC) | High Altitude Observatory". www2.hao.ucar.edu. Retrieved 2022-06-30.

- ^ "Mahattattva, Mahat-tattva: 5 definitions". Wisdom Library. February 10, 2021.

Mahattattva (महत्तत्त्व) or simply Mahat refers to a primordial principle of the nature of both pradhāna and puruṣa, according to the 10th century Saurapurāṇa: one of the various Upapurāṇas depicting Śaivism.—[...] From the disturbed prakṛti and the puruṣa sprang up the seed of mahat, which is of the nature of both pradhāna and puruṣa. The mahattattva is then covered by the pradhāna and being so covered it differentiates itself as the sāttvika, rājasa and tāmasa-mahat. The pradhāna covers the mahat just as a seed is covered by the skin. Being so covered there spring from the three fold mahat the threefold ahaṃkāra called vaikārika, taijasa and bhūtādi or tāmasa.

- ^ Gupta, S. V. (2010). "Ch. 1.2.4 Time Measurements". In Hull, Robert; Osgood, Richard M. Jr.; Parisi, Jurgen; Warlimont, Hans (eds.). Units of Measurement: Past, Present and Future. International System of Units. Springer Series in Materials Science: 122. Springer. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9783642007378.

- ^ Penprase, Bryan E. (2017). The Power of Stars (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 182. ISBN 9783319525976.

- ^ Johnson, W.J. (2009). A Dictionary of Hinduism. Oxford University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-19-861025-0.

- ^ Fernandez, Elizabeth. "The Multiverse And Eastern Philosophy". Forbes.

- ^

- Zimmer, Heinrich Robert (2018). Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-21201-2.

- Penprase, Bryan E. (2017). The Power of Stars. Springer. p. 137. ISBN 978-3-319-52597-6.

- Campbell, Joseph (2015). Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks, Eranos 3: Man and Time. Princeton University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4008-7485-9.

- Henderson, Joseph Lewis; Oakes, Maud (1990). The Wisdom of the Serpent: The Myths of Death, Rebirth, and Resurrection. Princeton University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-691-02064-8.

- ^ jones, prudence (2011-01-01), "Ptolemy", Dictionary of African Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195382075.001.0001/acref-9780195382075-e-1700, ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5, retrieved 2022-11-09

- ^ Swerdlow, N. M. (February 2021). "The Almagest in the Manner of Euclid". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 52 (1): 104–107. doi:10.1177/0021828620977214. ISSN 0021-8286.

- ^ Jackson, Roger; Makransky, John (2013). Buddhist Theology: Critical Reflections by Contemporary Buddhist Scholars. Routledge. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-136-83012-9.

- ^ Reat, N. Ross; Perry, Edmund F. (1991). A World Theology: The Central Spiritual Reality of Humankind. Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-521-33159-3.

- ^ India, Digital Branding Learners (2019-01-01). "Aryabhatta and the great Indian Mathematicians". Learners India.

- ^ Adi Setia (2004). "Fakhr Al-Din Al-Razi on Physics and the Nature of the Physical World: A Preliminary Survey". Islam & Science. 2. Archived from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ^ Misner, Thorne and Wheeler

- ^ Kirschner, Stefan (2021), Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), "Nicole Oresme", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2022-11-09

- ^ "Episode 11: The Legacy of Ptolemy's Almagest". www.aip.org. 2022-09-28. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ "Nicolaus Copernicus - University of Bologna". www.unibo.it. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ a b Berendzen, Richard (1975). "Geocentric to heliocentric to galactocentric to acentric: the continuing assault to the egocentric". Vistas in Astronomy. 17 (1): 65–83. Bibcode:1975VA.....17...65B. doi:10.1016/0083-6656(75)90049-5.

- ^ Staff (March 17, 2014). "BICEP2 2014 Results Release". National Science Foundation. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ^ Clavin, Whitney (March 17, 2014). "NASA Technology Views Birth of the Universe". NASA. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (March 17, 2014). "Space Ripples Reveal Big Bang's Smoking Gun". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (March 24, 2014). "Ripples From the Big Bang". New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Ade, P.A.R.; BICEP2 Collaboration (June 19, 2014). "Detection of B-Mode Polarization at Degree Angular Scales by BICEP2". Physical Review Letters. 112 (24): 241101. arXiv:1403.3985. Bibcode:2014PhRvL.112x1101B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.241101. PMID 24996078. S2CID 22780831.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "BICEP2 News | Not Even Wrong".

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (June 19, 2014). "Astronomers Hedge on Big Bang Detection Claim". New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (June 19, 2014). "Cosmic inflation: Confidence lowered for Big Bang signal". BBC News. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ^ Abbott, B. P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T. D.; Abernathy, M. R.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P. (2016-02-11). "Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger". Physical Review Letters. 116 (6): 061102. arXiv:1602.03837. Bibcode:2016PhRvL.116f1102A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 26918975. S2CID 124959784.

- ^ Castelvecchi, Davide; Witze, Alexandra (11 February 2016). "Einstein's gravitational waves found at last". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19361. S2CID 182916902. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ Blum, Alexander; Lalli, Roberto; Renn, Jürgen (12 February 2016). "The long road towards evidence". Max Planck Society. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ Abbott, B. P.; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration) (15 June 2016). "GW151226: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a 22-Solar-Mass Binary Black Hole Coalescence". Physical Review Letters. 116 (24): 241103. arXiv:1606.04855. Bibcode:2016PhRvL.116x1103A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.241103. PMID 27367379. S2CID 118651851.

- ^ Commissariat, Tushna (15 June 2016). "LIGO detects second black-hole merger". Physics World. Institute of Physics. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ "First-ever Image of a Black Hole Published by the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration". eventhorizontelescope.org. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ^ "The first picture of a black hole opens a new era of astrophysics". Science News. 2019-04-10. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ^ "How Does the Event Horizon Telescope Work?". Sky & Telescope. 2019-04-15. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ^ University of Geneva (10 March 2020). "Solved: The mystery of the expansion of the universe". Phys.org. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Lombriser, Lucas (10 April 2020). "Consistency of the local Hubble constant with the cosmic microwave background". Physics Letters B. 803: 135303. arXiv:1906.12347. Bibcode:2020PhLB..80335303L. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2020.135303. S2CID 195750638.

- ^ "Rethinking cosmology: Universe expansion may not be uniform (Update)". phys.org. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Nasa study challenges one of our most basic ideas about the universe". The Independent. 8 April 2020. Archived from the original on 2022-05-07. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Parts of the universe may be expanding faster than others". New Atlas. 9 April 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Doubts about basic assumption for the universe". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Migkas, K.; Schellenberger, G.; Reiprich, T. H.; Pacaud, F.; Ramos-Ceja, M. E.; Lovisari, L. (8 April 2020). "Probing cosmic isotropy with a new X-ray galaxy cluster sample through the LX–T scaling relation". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 636: A15. arXiv:2004.03305. Bibcode:2020A&A...636A..15M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201936602. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 215238834. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "The laws of physics may break down at the edge of the universe". Futurism. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "New findings suggest laws of nature 'downright weird,' not as constant as previously thought". phys.org. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Field, David (28 April 2020). "New Tests Suggest a Fundamental Constant of Physics Isn't The Same Across The Universe". ScienceAlert.com. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Wilczynska, Michael R.; Webb, John K.; Bainbridge, Matthew; Barrow, John D.; Bosman, Sarah E. I.; Carswell, Robert F.; Dąbrowski, Mariusz P.; Dumont, Vincent; Lee, Chung-Chi; Leite, Ana Catarina; Leszczyńska, Katarzyna; Liske, Jochen; Marosek, Konrad; Martins, Carlos J. A. P.; Milaković, Dinko; Molaro, Paolo; Pasquini, Luca (1 April 2020). "Four direct measurements of the fine-structure constant 13 billion years ago". Science Advances. 6 (17): eaay9672. arXiv:2003.07627. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.9672W. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay9672. PMC 7182409. PMID 32426462.

Bibliography

- Bunch, Bryan, and Alexander Hellemans, The History of Science and Technology: A Browser's Guide to the Great Discoveries, Inventions, and the People Who Made Them from the Dawn of Time to Today. ISBN 0-618-22123-9

- P. de Bernardis et al., astro-ph/0004404, Nature 404 (2000) 955–959.

- Horowitz, Wayne (1998). Mesopotamian cosmic geography. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-0-931464-99-7.

- P. Mauskopf et al., astro-ph/9911444, Astrophys. J. 536 (2000) L59–L62.

- A. Melchiorri et al., astro-ph/9911445, Astrophys. J. 536 (2000) L63–L66.

- A. Readhead et al., Polarization observations with the Cosmic Background Imager, Science 306 (2004), 836–844.