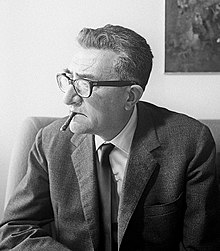

Riccardo Lombardi

Riccardo Lombardi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Transport | |

| In office 10 December 1945 – 1 July 1946 | |

| Prime Minister | Alcide De Gasperi |

| Preceded by | Ugo La Malfa |

| Succeeded by | Giacomo Ferrari |

| Member of the Constituent Assembly | |

| In office 25 June 1946 – 31 January 1948 | |

| Constituency | Single national constituency |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 8 May 1948 – 11 July 1983 | |

| Constituency | Milan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 16 August 1901 Regalbuto |

| Died | 18 September 1984 (aged 83) Rome |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Political party | Action Party (1942–47) Italian Socialist Party (1947–84) |

| Spouse | Ena Viatto |

| Alma mater | Polytechnic University of Milan |

| Profession | Engineer, journalist |

Riccardo Lombardi (16 August 1901 – 18 September 1984) was an Italian politician.[1]

Early life

Lombardi was born in Regalbuto, in the province of Enna (now in the province of Catania), in 1901. He studied at the Pennisi College of Acireale, and, after completing his high school studies, he attended the Polytechnic of Milan, where he obtained a degree in Industrial Engineering. He joined the Italian People's Party of Don Luigi Sturzo, thus sympathizing with the Christian Labor Party, founded in 1920 by left-wing members of the PPI, such as Guido Miglioli, to whom he was very attached. He participated in some actions of the Arditi del Popolo, including the defense of the socialist newspaper Avanti! from the assault of the fascist squads.

In 1923 he collaborated with Il Domani d'Italia, a newspaper of the Catholic left. When Italian Catholicism gave up actively opposing Fascism, he approached Marxist culture, also drawing inspiration from Antonio Gramsci, and, gradually, deviated from its own Catholic formation. After the suppression of political parties decreed on 5 November 1926 by the fascist regime, he continued to participate in clandestine activity with anti-fascist exponents of various tendencies, in particular with the communists whose activism he appreciated, while refusing to join the Communist Party of Italy.

In those years he met his partner, and then his wife, Ena Viatto (1906–1986), who fell in love with Lombardi and separated from Girolamo Li Causi. In 1930, following a leafleting action, he was attacked by the black shirts, then arrested and tortured with batons by the police at the Fascist headquarters. The beatings injured his lung and he never fully recovered from the after-effects of the violence.

Italian resistance and political activity

A leader of the Italian Resistance against Mussolini during World War II, he was one of the founders of the Action Party in 1942.[2]

He was member of the CLNAI from which at the Liberation he was appointed Prefect of Milan (from 30 April 1945 to December 1945): in this office he testified in favor of the former Fascist prefect of Milan Piero Parini. He participated in the first De Gasperi government (10 December 1945 – 1 July 1946) as Minister of Transport, starting the rapid reconstruction of the railway network.[3]

He represented the Action Party in the Constituent Assembly of Italy from 1946 to 1948 and the Italian Socialist Party in the Chamber of Deputies from 1948 to 1983.[4] In 1980, he was appointed president of the Italian Socialist Party.

Forged NATO document incident

On 18 June 1970 Lombardi made claims before the Italian Chamber of Deputies, based on a document printed on NATO stationery, that the organization was planning to move troops into Italy as a result of the perceived political instability.[5] Lombardi stated that he had received the document at the end of a meeting of NATO foreign ministers on 25 May 1970.[6][7]

The document was later rejected as a forgery by the Italian Foreign Ministry and by NATO headquarters.[6]

Death

Lombardi died of pulmonary fibrosis and respiratory failure at the Roman clinic Mater Dei and, by his explicit will, was cremated without religious rites.[8]

References

- ^ "Lombardi, Riccardo". Trecanni.

- ^ "Riccardo Lombardi". Statesman Journal. 19 September 1984.

- ^ Giuseppe Sircana, Riccardo Lombardi, Dizionario biografico degli italiani, Treccani

- ^ "Riccardo Lombardi (1901-1984)". La Fondazione di Studi Storici Filippo Turati.

- ^ Bittman, Ladislav (1985). The KGB and Soviet Disinformation: An Insider's View. McLean, Virginia: Pergamon-Brassey's. p. 104.

- ^ a b "A "NATO Document" Branded a Forgery". New York Times. 20 June 1970. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ Pisano, Vittorfranco S. (1987). The Dynamics of Subversion and Violence in Contemporary Italy. Hoover Press. ISBN 9780817985530.

- ^ E' MORTO A ROMA RICCARDO LOMBARDI

- 1901 births

- 1984 deaths

- Politicians from the Province of Enna

- Action Party (Italy) politicians

- Italian Socialist Party politicians

- Transport ministers of Italy

- Italian resistance movement members

- Members of the Constituent Assembly of Italy

- Deputies of Legislature I of Italy

- Deputies of Legislature II of Italy

- Deputies of Legislature III of Italy

- Deputies of Legislature IV of Italy

- Deputies of Legislature V of Italy

- Deputies of Legislature VI of Italy

- Deputies of Legislature VII of Italy

- Deputies of Legislature VIII of Italy

- People from Regalbuto