Mars Society

| |

| Formation | August 13, 1998[1] |

|---|---|

| Founder | Robert Zubrin |

| 31-1585646[2] | |

| Legal status | Nonprofit organization, 501(c)(3) eligible[2] |

| Focus | Advocacy for Mars exploration and colonization |

| Headquarters | Lakewood, Colorado, United States |

Region | Worldwide, with a focus at United States |

| Product |

|

| Website | www |

The Mars Society is a nonprofit organization that advocates for human Mars exploration and colonization. It was founded by Robert Zubrin in 1998 and based on Zubrin's Mars Direct philosophy, which aims to make human mission to Mars as lightweight and feasible as possible. The Mars Society aims to generate interest in the Mars program by garnering support from the public and lobbying. Many Mars Society members and former members are influential in the wider spaceflight community, such as Buzz Aldrin and Elon Musk.

Since its founding, the Mars Society has hosted its annual International Mars Society Convention and operated Mars analog habitats, called the Mars Desert Research Station and the Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station. Both of the stations are placed in remote locations and aims to replicate a true Mars mission for research. Crew members in the stations must perform mock extravehicular activities, do research assignments and live on strictly rationed supplies. The organization also hosts university robotics competitions, called the University Rover Challenge and the European Rover Challenge.

History

Background and founding

NASA had made technical studies for a human mission to Mars since the early 1960s; later however NASA diverted its resources to the development of the Space Shuttle.[3] Frustrated by the U.S. administration's ignorance to human missions to Mars, around 1978, a small network of space enthusiasts known as the Mars Underground emerged. In April 1981, the Mars Underground organized the first Case for Mars conference about Mars exploration at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Subsequent Case for Mars conferences were organized every three years[4]: 25–27 until the sixth and last Case for Mars conference in 1996.[3]

In 1983, Robert Zubrin, looking to reorient his career from being a teacher, applied and was accepted by the University of Washington to study nuclear fusion. He attended the third Case for Mars conference in 1987 and started working at Martin Marietta a year later.[5]: 259–260 In 1989, then-president George H. W. Bush announced the Space Exploration Initiative,[6] but with three-decade Mars exploration plan that was estimated to cost between $250 and $500 billion, the initiative was eventually canceled.[3]

After developing the Mars Direct human Mars mission plan as part of a research team in Martin Marietta,[5]: 260 Zubrin and engineer David Baker announced it to NASA and the public in early 1990.[7] The core tenet in the Mars Direct plan is to use existing technologies and eliminate the need for space rendezvous or precursor space station. A modified Mars Direct plan was priced by NASA at $20 billion, which is one-twentieth of the Mars plan in NASA's Space Exploration Initiative.[4]: 117 In 1996, Zubrin published The Case For Mars, the same year as when the last Case for Mars conference took place.[8] The book criticized prior Mars exploration mission proposals for being too costly and complicated, proposed an alternative mission plan based on the Mars Direct plan, gave philosophical arguments for it and rebutted criticisms of the plan.[9] The book's reception is positive, with over four thousand letters and emails sent to Zubrin by readers.[10]

The Mars Society was founded by Zubrin on 13 August 1998[1] in its first conference in Boulder, Colorado, which took place for four days and attended by 750 people.[8] The conference can be seen as a spiritual successor to the prior Case for Mars conferences.[4]: 27 Some of the invited attendees were from the Mars Underground and those who had written to Zubrin about The Case For Mars. The Mars Society's founding conference emphasize its focus at the Mars Direct plan and efforts of lobbying the government,[8] holding that there is no technical reason that would prevent a human mission to Mars within a decade.[10]

Construction of Mars analog habitats

The first Mars analog facility that is built by the Mars Society is the Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station (FMARS) on the Devon Island. The FMARS is the second Mars analog facility in the world; the first one is the Haughton–Mars Project, which contributed to FMARS's funding.[11] Part of the funding also came from various businesses, such as the Discovery Channel.[12] It was first occupied in July and August 2000,[13]: 98–99 and started the first simulated mission in 2001.[12]

In mid-2001, the Mars Society received a $5000 check from Elon Musk for a fundraiser event. Zubrin took notice and invited Musk for coffee. There, he talked about the Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station and the Translife Mission which included experiments where a spinning capsule would subject mice to Martian gravity. After briefly researching about Mars concepts and missions, Musk joined the Mars Society's board of directors and gave it $100,000.[14]: 99–100 The money that had been donated by Musk was spent on the next Mars analog habitat, called the Mars Desert Research Station (MDRS).[15] In December that year, the habitat's construction near Hanksville, Utah[16]: 4 was completed.[11]

Later activities and operations

In August 2001, Musk left the Mars Society after a meeting with its members and established a temporary foundation for his publicity projects.[17] However, by April 2002, Musk had abandoned them entirely; instead he founded SpaceX to build a low-cost rocket and invited aerospace engineers that he had met beforehand.[14]: 112 Since then, contact between Musk and the Mars Society was never cut off entirely, as evident by his presentation of the Falcon 1 rocket in 2008[18] and participation at the society's 2020 convention.[19]

After FMARS's testing was complete, from 2001 to 2005, Mars mission simulations there were usually 2–8 weeks long and consisted of ten rotated crews. The first four-month-long mock mission was done in 2007, which revealed cultural conflicts and inadequate coping strategies. Shorter missions were done in 2009 and 2013, before another long-duration mission called Mars 160 was conducted in 2017, in collaboration with the MDRS. The crew would stay for eighty days in MDRS before being transferred to FMARS, rotating the crew for every month.[13]: 99, 101 As of April 2020, the MDRS has hosted nineteen Mars mission simulations, totaling 236 crews in 6–7 people batches in missions lasting from 1–2 weeks.[13]: 101

At the Mars Society's 2015 convention, a debate was organized between two representatives of Mars One (CEO Bas Lansdorp and Barry Finger) and two researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Sydney Do and Andrew Owens).[20] Mars One was an organization that aimed to land human on Mars, which had been criticized by the researchers for being infeasible and suicidal.[21] According to Dwayne A. Day from The Space Review, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology team had won the debate for making specific and realistic arguments. He also noted how Mars One popularity has dwarfed the Mars Society and this might potentially damage the society's reputation.[20]

Organization

The Mars Society is a nonprofit organization that is funded by donations[22] and operated by volunteers.[23] Its aims are garnering support for human Mars missions from the public, lobbying government and space agencies, and research about the effects on Martian crews via Mars analog habitats.[24]: xv–xvi [25] The Mars Society's founder and current president is Robert Zubrin, and notable members and former members of the organization include Buzz Aldrin,[26] Elon Musk,[14] Gregory Benford,[26] and Peter Smith.[27] Membership to the Mars Society is available for all with a small fee.[24]: xvi

Many of the Mars Society's members believe that a human mission to Mars is in reach within a decade (if longer, new U.S. administrations may cancel the program)[8] and that such a mission would lay the foundation for the colonization of Mars.[28]: 10–11 This philosophy has permeated through the society's lobbying efforts, such as in Zubrin's testimony of Mars exploration to the 2009 Augustine Commission, a panel made by the Obama administration for guiding U.S. human spaceflight program. However, in the final report, the commission concluded that such a mission would "demand decades of investment and carry considerable safety risk to humans" at the time, contrary to the Mars Society's ethos.[29]

Since its founding in the U.S., the Mars Society has chapters around the world in Canada, Australia, Japan, many European countries, etc.[24]: xv–xvi The society is also a member of the Alliance for Space Development, a space advocacy organization that promotes space colonization.[30]

Projects

Mars Analog Research Station Program

The Mars Analog Research Station Program studies the technical and human factors of a Mars mission, via its two Mars analog habitats: the FMARS and the MDRS. The FMARS is located on the Devon Island in Canada and near the Haughton impact crater,[13]: 98, 101 above the 75th parallel north where the island is not inhabited and vegetated. The MDRS is located near Hanksville, Utah, where the habitat is isolated from civilization. Both stations' location are chosen for its similarities to Mars,[16]: 4 and are closed to public visits.[10]

Additional analog stations are planned by the Mars Society. The Euro-MARS was operated by the Mars Society's European chapter and was to feature three decks and more extensive facilities. However, during transport from the United Kingdom to its deployment location in Krafla, Iceland, the Euro-MARS was damaged and as of 2017 is back at the planning phase.[31] The Mars Society is also planning to build another Mars analog station in Arkaroola, Australia, as of October 2022.[32] The station would replicate a spacecraft launching directly from the Earth's surface, featuring a mock propulsion module, heat shield and landing engines.[31]

Design of the stations

Both stations originally had the same basic design:[13]: 104 a two-level habitat module 8 m (26 ft) in diameter. The habitat's lower level has a bathroom, laboratory, two airlocks, an extravehicular activity preparation area and stores various engineering equipment; at the top, the habitat's upper level has six sleeping quarters for each crew, a common area, computing area and galley (kitcken). The loft level above the sleeping quarter is used for storage.[16]: 3

Later on, there were drastic differences between the FMARS and MDRS, due to FMARS's more isolated location and MDRS's more continuous use, maintenance and expansion. The FMARS also needs to withstand the extreme wind and temperature in the Arctic. A participant of Mars 160 described the FMARS as more structurally sound, though more deteriorated due to dry rot and molds. Power and internet access was limited to a few hours per day and many pieces of equipment were broken because of poor maintenance.[13]: 104–105

The FMARS is a monocoque mostly made out of double-skinned wood panels. The habitat is stabilized by ground trusses and steel guy-wires, making the FMARS more stable than MDRS in high wind. The lower desk has more but smaller rooms, and the doors in the FMARS are square and tall. A ladder connects both floors together. The galley's and ladder's position are swapped compared to the MDRS, as well as the toilet and bathroom. The upper deck's shared space is used for both computing and dining, and the galley consists of a stove, microwave, and a water container. The crew quarter's rooms have staggered bunk beds and are not equal in volume. A nearby river a few hundred meters away provides freshwater, and a gas generator provides electricity.[13]: 98–100

The MDRS is expanded from the two-level habitat (called Hab) to include a greenhouse (GreenHab), solar observatory (Musk Observatory), a science building (Science Dome), an engineering pod (RAM), and a robotic observatory.[13]: 103 The Musk Observatory is named after Elon Musk, who donated $100,000 to the MDRS.[15]

Except for the robotic observatory, the modules are connected via tunnels. At the habitat, the lower deck is used for science and engineering activities. Like the FMARS, it has a shower and toilet, a biology and geology laboratory, two simulated airlocks, an extravehicular activity preparation area, and storage space. The upper deck is used for social activities, dining and communications, and has seven separate crew quarters. In the loft area, a tank stores freshwater and a hatch is used for maintaining antenna and weather instruments. Water for flushing the toilet is provided by the greenhouse, and electricity is provided by batteries under the habitat.[13]: 103–104

Crew members' operations

With a few safety exceptions, crew outside the habitat must wear mock space suits.[16]: 3 All food and supplies are at the habitat or being supplied by the crew, and there is no resupplying while a mission is in progress. Because there are very few spare parts on-site, crews must be able to repair broken equipment themselves. To simulate Earth–Mars six- to forty-minutes communication delay, a twenty-minute lag time is usually added for crew communication with the mission support team.[16]: 12 Therefore, crews cannot rely on real-time assistance and must be able to perform tasks by themselves.[16]: 13

Each batch of habitat crew has a mission commander, an executive officer, and various scientists and engineers,[16]: 12 assisted by a mission support team. The crew are responsible for mission planning and task prioritizing, as well as writing a daily summary report.[16]: 13 The crew member must also perform a research study, which is reviewed beforehand by an ethics committee. Over 1400 studies have been performed at the MDRS, more than any other Mars analog habitats. The impact of crew composition, such as gender and cultural factors, has been studied at the station. However, due to the short duration of the MDRS missions, studies of a Mars mission's habitability impact have been limited.[13]: 104

Other projects

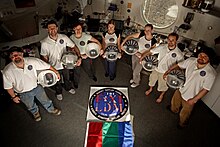

Since its founding in 1998, the society has organized annual conventions.

The Mars Society organizes annual student competitions for making mock Martian rovers which are collectively called the Rover Challenge Series. Around May and June each year, the three-day University Rover Challenge takes place on Utah's desert near the MDRS where teams compete in exploration tasks. The rover's operators must only use sensors data for navigation, similar to actual Martian rovers. Similar regional competitions that belong to the Rover Challenge Series include the European Rover Challenge, Canadian International Rover Challenge, and the Indian Rover Challenge.[33]: 65-66

In collaboration with a virtual reality company,[34] MarsVR aims to simulate living at the MDRS with real terrain from one square mile around the base. MarsVR is expected to train MDRS's crews by simulate using spacesuits, airlock, rover, and cooking. The exploration portion of MarsVR is free, however, the training part is paid for the public.[35] The software can also simulate playing sports on Mars such as soccer and mountaineering.[34]

See also

References

- ^ a b The Mars Society members (1999). Zubrin, Robert M.; Zubrin, Maggie (eds.). Proceedings of the Founding Convention of the Mars Society: held August 13-16, 1998, Boulder, Colorado. Univelt. Citation at the title. ISBN 9780912183121. OCLC 47665501.

- ^ a b "Privacy Policy". The Mars Society. 25 June 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

We are The Mars Society — an international movement — legally, we are a non-profit 501(c)(3) registered in Colorado in the United States. Our EIN is 31-1585646.

- ^ a b c S. F. Portree, David (March 2000). "The Road to Mars..." Air & Space/Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Hogan, Thor (May 2007). "Mars Wars – The Rise and Fall of the Space Exploration Initiative" (PDF). NASA (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b Morton, Oliver (2003). Mapping Mars: Science, Imagination, and the Birth of a World. Picador. ISBN 978-0312422615.

- ^ Cobb, Wendy Whitman (5 December 2018). "George H.W. Bush's overlooked legacy in space exploration". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Portree, David S. F. (15 April 2013). "Mars Direct: Humans to Mars in 1999! (1990)". Wired. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d Blakeslee, Sandra (18 August 1998). "Society Organizes to Make a Case for Humans on Mars". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Spitzmiller, Ted (1 November 2007). "Book Review: The Case for Mars". National Space Society. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Conroy, J Oliver (17 February 2022). "Life on 'Mars': the strangers pretending to colonize the planet – in Utah". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b Bishop, Sheryl L. (2011). "From Earth Analogs to Space: Getting There from Here". In Vakoch, Douglas A. (ed.). Psychology of Space Exploration (PDF). Washington, DC: NASA. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-16-088358-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ a b Hall, James (8 March 2002). "Finding Mars on Earth". Science. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Häuplik-Meusburger, Sandra; Bishop, Sheryl; O’Leary, Beth (2021). Vakoch, Douglas A. (ed.). Space Habitats and Habitability: Designing for Isolated and Confined Environments on Earth and in Space (1st ed.). Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-3030697396.

- ^ a b c Vance, Ashlee (2015). Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-230123-9. OCLC 881436803.

- ^ a b Messeri, Lisa (9 September 2016). Placing Outer Space: An Earthly Ethnography of Other Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 200, note 19. ISBN 978-0-8223-6187-9. OCLC 926821450.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cusack, Stacy L. (1 January 2010). Observations of Crew Dynamics during Mars Analog Simulations (PDF). NASA Project Management Challenge 2010. Galveston, Texas. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022 – via NASA Technical Reports Server.

- ^ "MarsNow 1.9 Profile: Elon Musk, Life to Mars Foundation". SpaceRef. 25 September 2001. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (8 September 2008). "Looking (far) ahead". The Space Review. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Mack, Eric (16 October 2020). "Elon Musk will share his latest moon and Mars plans with all Earthlings today". CNET. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ a b Day, Dwayne (17 August 2015). "Red planet rumble". The Space Review. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Grush, Loren (18 August 2015). "Mars One debates MIT: CEO Bas Lansdorp still doesn't have a plan to reach the planet". The Verge. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Bichell, Rae Ellen (6 July 2017). "To Prepare For Mars Settlement, Simulated Missions Explore Utah's Desert". NPR. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ McGrath, Dianne (9 April 2020). "What a simulated Mars mission taught me about food waste". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Pletser, Vladimir (2018). On To Mars!: Chronicles of Martian Simulations. Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-7030-3. ISBN 978-981-10-7030-3.

- ^ "About the Mars Society". Mars Society. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ a b Goodyear, Dana (19 October 2009). "Man of Extremes". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ "Steering Committee – 2022". Mars Society. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Rapp, Donald (2016). Human missions to Mars : enabling technologies for exploring the red planet (2nd ed.). Cham: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-3-319-22249-3. OCLC 927404673.

- ^ Benson, Eric; Nobel, Justin (9 January 2010). "Mars or Bust". Guernica. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (26 February 2015). "New Alliance to Promote Space Development and Settlement". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ a b Vargas-Cuentas, Natalia I.; Roman-Gonzalez, Avid (June 2017). The 'Salar de Uyuni' as a simulated Mars base habitat in South America. Global Space Exploration Conference. pp. 5–6. Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2022 – via HAL (open archive).

- ^ Stoltz, Michael (29 October 2022). "Building a Mars Analog "Down Under"". The Mars Society. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ Wieczorek, Luiza; Piech, Wiktor; Cybulski, Bartłomiej; Kujawiński, Mateusz; Węgierska, Agnieszka (30 December 2018). "Participation in international robotics competitions as a new form of student travel". Turyzm (Tourism). 28 (2): 63–72. doi:10.2478/tour-2018-0016. ISSN 2080-6922.

- ^ a b Murphy, Jen (1 July 2022). "Why Sports in Space Could Be the Next Big Thing". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Rayome, Alison DeNisco (3 March 2020). "The future of Mars colonization begins with VR and video games". CNET. Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.