1939 New York World's Fair

| 1939 New York City | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | Second category General Exposition |

| Name | New York World's Fair |

| Motto | The World of Tomorrow |

| Area | 1,202 acres (486 hectares) |

| Organized by | Grover Whalen |

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 33 |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| City | New York City |

| Venue | Flushing Meadows–Corona Park |

| Coordinates | 40°44′39″N 73°50′40″W / 40.74417°N 73.84444°W |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | April 30, 1939[1] |

| Closure | October 27, 1940 |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in Paris |

| Next | Exposition internationale du bicentenaire de Port-au-Prince in Port-au-Prince |

| Specialized Expositions | |

| Previous | Second International Aeronautic Exhibition (1938) in Helsinki |

| Next | International Exhibition on Urbanism and Housing (1947) in Paris |

| Simultaneous | |

| Universal | Golden Gate International Exposition |

| Specialized | Exposition internationale de l'eau in Liège |

The 1939–40 New York World's Fair was a world's fair held at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, New York, United States. It was the second-most expensive American world's fair of all time, exceeded only by St. Louis's Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904. Many countries around the world participated in it, and over 44 million people attended its exhibits in two seasons.[2] It was the first exposition to be based on the future, with an opening slogan of "Dawn of a New Day", and it allowed all visitors to take a look at "the world of tomorrow".

When World War II began four months into the 1939 World's Fair, many exhibits were affected, especially those on display in the pavilions of countries under Axis occupation. After the close of the fair in 1940, many exhibits were demolished or removed, though some buildings were retained for the 1964–1965 New York World's Fair, held at the same site.

Planning

In 1935, at the height of the Great Depression, a group of New York City businessmen decided to create an international exposition to help lift the city and the country out of its economic woes. Not long after, these men formed the New York World's Fair Corporation, whose office was placed on one of the higher floors in the Empire State Building. The NYWFC, which elected former chief of police Grover Whalen as president, also included Winthrop Aldrich, Mortimer Buckner, Floyd Carlisle, Ashley T. Cole, John J. Dunnigan, Harvey Dow Gibson, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, Percy S. Straus, and many other business leaders.

Over the next four years, the committee planned, built, and organized the fair and its exhibits, with countries around the world taking part in creating the biggest international event since World War I. Working closely with the Fair's committee was New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, who saw great value to the city in having the World's Fair Corporation (at its expense) remove a vast ash dump in Queens that was to be the site for the exposition. This event turned the area into a City park after the exposition closed.

Edward Bernays directed public relations of the fair in 1939, which he called "democracity."[3] Grover Whalen, a public relations innovator, saw the Fair as an opportunity for corporations to present consumer products, rather than as an exercise in presenting science and the scientific way of thinking in its own right, as Harold Urey, Albert Einstein, and other scientists wished to see the project.[4] "As events transpired," reported Carl Sagan,[5] whose own interest in science was nevertheless sparked by the Fair's gadgetry, "almost no real science was tacked on to the Fair's exhibits, despite the scientists' protests and their appeals to high principles."

Promotion of the Fair took many forms. During the 1938 Major League Baseball season, the Brooklyn Dodgers, New York Giants, and New York Yankees promoted the event by wearing patches on the left sleeve of their jerseys featuring the Trylon, Perisphere, and "1939." The same year, Howard Hughes flew a special World's Fair flight around the world to promote the fair.

While the main purpose of the fair was to lift the spirits of the United States and drive much-needed business to New York City, it was also felt that there should be a cultural or historical association. It was therefore decided for the opening to correspond to the 150th anniversary of George Washington's first inauguration as President of the United States, and WPA artists painted murals which appeared in The New York Times Magazine.[6]

According to the official pamphlet:

The eyes of the Fair are on the future—not in the sense of peering toward the unknown nor attempting to foretell the events of tomorrow and the shape of things to come, but in the sense of presenting a new and clearer view of today in preparation for tomorrow; a view of the forces and ideas that prevail as well as the machines. To its visitors the Fair will say: "Here are the materials, ideas, and forces at work in our world. These are the tools with which the World of Tomorrow must be made. They are all interesting and much effort has been expended to lay them before you in an interesting way. Familiarity with today is the best preparation for the future.

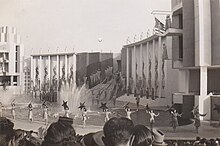

Grand opening

On April 30, 1939, a very cloudy Sunday, the fair had its grand opening, with 206,000 people in attendance. The April 30 date coincided with the 150th anniversary of George Washington's inauguration, in Lower Manhattan, as the first President of the United States. Although many of the pavilions and other facilities were not quite ready for this opening, it was put on with pomp and great celebration.[citation needed]

Plans for the United States Navy Fleet to visit New York City for the opening of the fair following maneuvers in the Caribbean were canceled, however, due to aggressive moves being made by Japan in the South China Sea, and the fleet instead transferred to the Pacific via the Panama Canal in April.[7]

David Sarnoff, then president of RCA and a strong advocate of television, chose to introduce television to the mass public at the RCA pavilion. As a reflection of the wide range of technological innovation on parade at the fair, Franklin D. Roosevelt's speech was not only broadcast over the various radio networks but also was televised along with other parts of the opening ceremony and other events at the fair. That day, the opening ceremony and President Roosevelt's speech were seen on black and white television sets with 5 to 12-inch tubes.[8] NBC used the event to inaugurate regularly scheduled television broadcasts in New York City over their station W2XBS (now WNBC). An estimated 1,000 people viewed the Roosevelt telecast on about 200 television sets scattered throughout the New York metropolitan area.[citation needed]

In order to convince skeptical visitors that the television sets were not a trick, one set was made with a transparent case so that the internal components could be seen. As part of the exhibit at the RCA pavilion, visitors could see themselves on television. There were also television demonstrations at the General Electric and Westinghouse pavilions. During this formal introduction at the fair, television sets became available for public purchase at various stores in the New York City area.[8]

After Albert Einstein gave a speech that discussed cosmic rays, the fair's lights were ceremonially lit. Dignitaries received a special Opening Day Program which contained their names written in Braille.[citation needed]

- 1939 World's Fair ephemera

-

This 1940 general admission ticket also included visits to "5 concessions" (listed on backside)

-

Ticket backside

-

Trylon and Perisphere on 1939 US stamp

Exhibits

One of the first exhibits to receive attention was the Westinghouse Time Capsule, which was not to be opened for 5 millennia (the year 6939). The time capsule was a tube containing writings by Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann, copies of Life Magazine, a Mickey Mouse watch, a Gillette safety razor, a kewpie doll, a dollar in change, a pack of Camel cigarettes, millions of pages of text on microfilm, and much more. The capsule also contained seeds of foods in common use at the time: (alfalfa, barley, carrots, corn, cotton, flax, oats, rice, soy beans, sugar beets, tobacco, and wheat, all sealed in glass tubes). The time capsule is located at 40°44′34.089″N 73°50′43.842″W / 40.74280250°N 73.84551167°W, at a depth of 50 feet (15 m). A small stone plaque marks the position.[9] Westinghouse also featured "Elektro the Moto-Man": the 7-foot (2.1 m) tall robot that talked, differentiated colors, and even "smoked" cigarettes.[10]

On July 3, 1940, the fair hosted "Superman Day". Notable was the crowning of the "Super-Boy and Super-Girl of the Day" following an athletic contest, and a public appearance by Superman, played by an unidentified man. Broadway actor Ray Middleton, who served as a judge for the contest, is often credited with having appeared in the Superman costume on Superman Day, but he did not; however, he may have played Superman during a live radio broadcast from the scene. Although the unknown man in the costume is often said to have been the first actor ever to play Superman, Bud Collyer had been performing the role on the Superman radio series since the preceding February.

The fair was also the occasion for the 1st World Science Fiction Convention, subsequently dubbed "Nycon 1".[11][12]

Ralph Vaughan Williams composed his work for harp and string orchestra Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus on commission from the World's Fair. The first performance was at Carnegie Hall in June 1939, conducted by Adrian Boult.[13] In addition, the British Council commissioned a piano concerto from Arthur Bliss for the British Week at the World's Fair. Adrian Boult conducted the New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra in Carnegie Hall on June 10, 1939, with Solomon as the soloist.[14]

Ceramic sculptor Waylande Gregory created The Fountain of the Atom, which displayed the largest ceramic sculptures in modern times.[15] It included the four Elements, each measuring 72 inches (180 cm) high and each weighing over a ton. There were also eight electrons, which were illustrated in Life Magazine (March 1939). Gregory also created two exhibitions featuring his ceramic sculptures for the General Motors Building, American Imports and American Exports.

Nylon fabric, the View-Master, and Scentovision (an early version of Smell-O-Vision) were introduced at the Fair. Other exhibits included Vermeer's painting The Milkmaid from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam,[16] a streamlined pencil sharpener, a diner (still in operation as the White Mana in Jersey City, New Jersey), a futuristic car-based city by General Motors, the first fully constructed computer game, and early televisions.[17] There was also a huge globe/planetarium located near the center of the fair. Bell Labs' Voder, a keyboard-operated speech synthesizer, was demonstrated at the Fair.

Zones

The fair was divided into seven geographic or thematic zones, five of which had "Focal Exhibits", as well as two Focal Exhibits housed in their own buildings.[18]: 46–47 Virtually every structure erected on the fairgrounds was architecturally distinguished, and many of them were experimental in many ways. Architects were encouraged by their corporate or government sponsors to be creative, energetic and innovative. Novel building designs, materials and furnishings were the norm. Many of the zones were arranged in a semicircular pattern, centered on the Wallace Harrison and Max Abramovitz-designed Theme Center, which consisted of two all-white, landmark monumental buildings named the Trylon (over 700 feet (210 m) tall) and the Perisphere which one entered by a moving stairway and exited via a grand curved walkway named the "Helicline". Inside the Perisphere was a "model city of tomorrow that visitors" viewed from a moving walkway high above the floor level. The zones were distinguished by many color cues, including different wall colors and tints and differently colored lighting.

The showcases were not only intended to get people to buy the sponsor's products, they were also intended to educate and inform the populace about basic materials and processes that were then very new and not well known. Many experimental product concepts and new materials were shown that were not currently available for purchase but became available in various ways over the next few years. In many ways, the fair pavilions more resembled a modern-day government-sponsored science fair exhibit than they resembled modern corporate advertising and sales promotions.[original research?]

Communications and Business Systems Zone

Fairgoers walking to the north of the Theme Center on the Avenue of Patriots would encounter the Communications and Business Systems exhibits. The focal point of this area was the Communications Building, a large structure with a pair of 160-foot-high (49 m) pylons flanking it.[18]: 73 [19]: 39

At the AT&T Pavilion the Voder, a mechanized, synthetic voice, spoke to attendees, foretelling the widespread use of electronic voices decades later.[18]: 77 The Business Systems and Insurance Building, an L-shaped structure, housed numerous companies such as Aetna, MetLife, and IBM. In particular, the IBM pavilion displayed electric typewriters and an "electric calculator" that used punched cards.[18]: 79

Next door to these business exhibits, on the "Street of Wheels", was the "Masterpieces of Art" building housing 300 priceless works of the Old Masters, from the Middle Ages to 1800. Whalen and his team were able to borrow paintings and sculptures from Europe. Thirty five-galleries featured great works from DaVinci and Michelangelo to Rembrandt, from Hals to Caravaggio and Bellini.[18]: 81–82

Community Interest Zone

The Community Interest Zone was located just east of the Communications & Business Systems Zone.[19]: 79 The region's exhibits showcased several trades or industries that were popular among the public at the time. It included buildings dedicated to home furnishings, plumbing, contemporary art, cosmetics, gardens, the gas industry, fashion, jewelry, and religion. Organizations such as the American Standard Companies, Christian Science, Johns Manville, Works Progress Administration, and YMCA also had buildings in the Community Interest Zone.[18]: 85–101 In addition, there was also the "Electrified Farm", a working farm,[18]: 91 and the Town of Tomorrow, which included 15 "demonstration homes" on a bowling green adjacent to the World's Fair station of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company.[18]: 100

Government Zone

The Government Zone was located at the east end of the fair, on the eastern bank of the Flushing River. It contained 21 pavilions, several smaller buildings, a centrally located Court of Peace, a Lagoon of Nations, and a smaller Court of States. The 60 foreign governments contributed a wide diversity of creatively designed pavilions housing a myriad of cultural offerings to fairgoers.[18]: 116–117 [19]: 55

British Pavilion

The Pavilion of Great Britain and the British Colonial Empire consisted of two buildings with a first-floor connection. The copy of Magna Carta belonging to Lincoln Cathedral also left Britain in 1939 for the first time to be in the British Pavilion at the fair.[18]: 129 Within months Britain joined World War II and it was deemed safer for it to remain in America until the end of hostilities. It therefore remained in Fort Knox, next to the original copy of the American constitution, until 1947.[citation needed] The pavilion included a collection of stamps celebrating Rowland Hill, and the 100th anniversary of the postage stamp. One of the stamps was the British Guiana 1c magenta.[20]

French Pavilion

The French pavilion, on the Court of Peace that was the grand open space northeast of the Theme Center, was a two-story structure whose facade featured enormous windows with "majestic curves".[18]: 127–128 After the fair closed and World War II ended, its French restaurant remained in New York City as Le Pavillon.[citation needed]

Greek Pavilion

The Greek pavilion was in the Hall of Nations and was a mirror of how the Metaxas quasi-fascist regime wanted to show Greece to the world.[18]: 130 The interior rooms were designed by Nelly, the famous Greek photographer. Nelly's collages expressed four aspects of Greece: the legacy of ancient Greece, the Christian spirituality, picturesque landscapes and the Greek racial continuity. On one of its outside walls there were four big murals featuring four historic episodes of Greek history, authored by Gerasimos Steris. After the Fair concluded, the pavilion was dismantled and parts of it were donated for the construction of the Greek Orthodox cathedral of Saint Nicholas in Tarpon Springs, Florida.[21]

Italian Pavilion

The Italian pavilion attempted to fuse ancient Roman splendor with modern styles, and a 200-foot (61 m) high waterfall dedicated to Guglielmo Marconi, the inventor of the radio defined the pavilion's facade. The pavilion occupied 100,000 square feet of space on plot GJ-1 at Presidential Row North and Continental Avenue and cost more than $3 million.[22]: 197 Italy paid for the right to use another ten thousand feet of space in the fair's Hall of Nations.[22] There, the mosaic floor was to be graced by a high pillar upon which rested the ubiquitous She-Wolf, mother of Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome. Above Nino Giordano's Capitoline She-Wolf extended the lines of a Roman triumphal arch. The long side walls, adorned with emblems of ancient and modern Rome and maps of its new colonial 'empire' were divided into three sections by columns with rostra rising on a plinth of black marble and accentuated by Roman stucco of a velvety-white color. These walls sheltered Romano Romanelli's bronze statue of Mussolini which stood tall upon a black marble pedestal in the very center of the room.[22]: 198

The pavilion's popular restaurant was designed in the shape of the nation's luxury cruise line ships.[18]: 133, 135

Japanese Pavilion

The Japanese pavilion was designed by the Japanese-American architect Yasuo Matsui to resemble a traditional Shinto shrine, set within a Japanese garden. It offered tea ceremony and Japanese flower arrangement exhibits.[18]: 135–136 The interior had a "Diplomat room", which featured a reproduction of the Liberty Bell made out of Japanese pearls and diamonds, worth $1 million. This room also featured a photomontage mural across which was written the motto "Dedicated to Eternal Peace and Friendship between America and Japan".[23]

The interior of the pavilion was designed by the Japanese architect and photographer Iwao Yamawaki, who studied at the Bauhaus school in Germany in the early 1930s.[24]

Jewish Palestine Pavilion

The Jewish Palestine Pavilion introduced the world to the concept of a modern Jewish state, which a decade later became Israel. The pavilion featured a monumental hammered copper relief sculpture on its facade titled The Scholar, The Laborer, and the Tiller of the Soil by Art Deco sculptor Maurice Ascalon.[18]: 136

Netherlands Pavilion

This exhibit presented a comprehensive survey of the cultural importance of the three parts of the empire: the Kingdom of Europe, the Dutch East Indies and the territories of Suriname and Curaçao in South America.[25]

Pan American Union Pavilion

The 21 countries of the Pan-American Union, as well as several communications companies, were represented in the Pan American Union Pavilion. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Venezuela, Cuba, Mexico, and Nicaragua were among the cooperating countries.[18]: 141

The Good Neighbor policy at the 1939 World's Fair was an extension of Franklin D. Roosevelt's Good Neighbor policy, which sought to redefine negative Latin American stereotypes.[26] Each country seized the opportunity to showcase their country and to make it more appealing to those around the world, especially in the United States. In their bid to increase cultural awareness at the World's Fair, the countries promoted tourism and strove to compare itself to the United States in an effort to appeal to Americans.[27]

Polish Pavilion

The Polish Pavilion was composed of steel tower with gold-plated copper shields and a sandstone building plus Polish restaurant in a round building. The Second Polish Republic prepared some 200 tons of artifacts, including a royal carpet of King Casimir IV, seven paintings presenting important events of Polish history, 150 contemporary Polish paintings, a gunmetal monument of Józef Piłsudski, armor of a Polish hussar from Kórnik Castle, ancient Polish weaponry (14th–18th centuries), a bell manufactured for the purpose of the Fair, folk costumes, house furniture from different regions of the country, and over 200 examples of Polish inventions like the first Polish streamlined steam locomotive Pm36-1 dated 1937 reaching 86 mph (140 km/h).[18][28]: 143

Swedish Pavilion

The Swedish pavilion “Swedish Modern – A movement towards sanity in design” was designed by Sven Markelius and highlighted the progress of democracy and welfare in Sweden. The pavilion buildings were grouped around a central garden and included a restaurant and a cinema, as well as a 2.8 meter tall Dalecarlian horse.[29]

USSR Pavilion

The USSR (Soviet) Pavilion was a semicircular structure with two wings partially enclosing a courtyard.[18]: 148 Exhibitions included the life-size copy of the interior of the showcase Mayakovskaya station of the Moscow Metro, whose designer Alexey Dushkin was awarded Grand Prize of the 1939 World's Fair.[30] The USSR Pavilion's courtyard contained a statue on a pylon, which was 260 feet (79 m) tall.[31][32] The pavilion was only open for 1939 and was razed at the end of that year.[33]

United States (Federal) Building

The United States Federal Building's main building was set between two 150-foot (46 m) pylons. The Federal Building and several surrounding structures contained a combined 23 exhibits, dedicated to 22 states and Puerto Rico.[18]

Midway through the fair, the world's largest carillon was installed in the spire of the Florida state exhibition building. The instrument was constructed by J. C. Deagan, Inc; it consisted of 75 tubular bells and weighed 25 tons. The instrument was donated by the Florida's Stephen Foster Memorial Association. After the fair, the carillon was moved to White Springs, Florida, in the campanile of the Stephen Foster Folk Culture Center on the banks of the Swanee River.[34] The installation, which added more bells, didn't complete until 1957.[35]

Food Zone

Southwest of the Government Zone was the Food Zone, composed of 13 buildings in total (excluding the Turkey and Sweden exhibits, which were physically located within the Food Zone but considered part of the Government Zone). Its Focal Exhibit was Food No. 3, a rhomboidal structure with four shafts representing wheat stalks.[18]: 102–103 [19]: 45

Among the many unique exhibits was the Borden's exhibit, that featured 150 pedigreed cows (including the original Elsie) on a Rotolactor that allowed bathing them, drying them, and milking them in a highly mechanized way. While no such complete system ever became common in milk production, many of its features came into everyday use in today's rotary milking parlors.[18]: 105, 107 Next door was the Continental Baking building, presenting a vast, continuous process of baking breads and other products, and was fashioned in the shape of a huge packaged bread loaf.[18]: 109

Production and Distribution Zone

The Production and Distribution Zone was dedicated to showcasing industries that specialized in manufacturing and distribution.[18]: 175 [19]: 87 The focal exhibit was the Consumers Building, a L-shaped structure occupying a triangular plot on the Avenue of Pioneers, illustrated with murals by Francis Scott Bradford.[18]: 175–178 Numerous individual companies hosted exhibitions in this region. There were also pavilions dedicated to a generic industry, such as electrical products, industrial science, pharmaceuticals, metals, and men's apparel.[18]: 176–195

Transportation Zone

The Transportation Zone was located west of the Theme Center, across the Grand Central Parkway.[19]: 25 Perhaps the most popular of the Transportation Zone pavilions was the one built for General Motors (GM), which contained the 36,000-square-foot (3,300 m2) Futurama exhibit, designed by famed industrial designer and theater set designer Norman Bel Geddes, which transported fair visitors over a huge diorama of a fictional section of the United States with miniature figures. Along the way, visitors would encounter increasingly larger figures until they exited into a representation of a life-size city intersection.[36] Stores in the GM Pavilion included an auto dealership and an appliance store where visitors could see the latest GM and Frigidaire products.[18]: 207–209

Adjacent to the GM Pavilion was the Ford Pavilion, where race car drivers drove on a figure eight track on the building's roof endlessly, day in and day out.[18]: 205, 207 Not far from GM and Ford was the focal exhibit of the Transportation Zone, a Chrysler exhibit group. In the focal exhibit, an audience could watch a Plymouth being assembled in an early 3D film in a theater with air conditioning, then a new technology.[18]: 199–201 Other structures included an aviation and marine transport building, as well as exhibits for the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company and Goodrich Corporation.[18]: 202, 204–205, 208–209

Another large building was the Eastern Railroads Presidents' Conference, dedicated to rail transport.[18]: 202–204 The centerpiece of the Railroad Conference exhibits (on seventeen acres) was Railroads on Parade, a spectacular live drama re-enacting the birth and growth of railroads. It had music by Kurt Weil and choreography by Bill Matons.[37] In addition to the show, there were important historical objects on display by the various railroads and manufacturing companies, such as the Tom Thumb engine. The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) had its S1 engine on display, mounted on rollers under the driver wheels and running continuously at 60 mph (97 km/h) all day long. The Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad had its own 4-6-0, #169, on display. The British London Midland & Scottish Railway sent their Coronation Scot express train with a locomotive LMS Princess Coronation Class 6229 Duchess of Hamilton, (disguised as sister locomotive 6220 Coronation), to the fair.[38][39] GM's Electro-Motive Division had a display of their then new streamlined diesel-electric passenger locomotives. The Italian state railways displayed one of their record-setting ETR 200 electric multiple unit train reaching 126 mph (203 km/h).

Amusement Area

Beyond the corporate and government zones, the wildly popular but less uplifting Amusements Area was not integrated into the thematic matrix, and was classified as an Area rather than a Zone. It was located south of the World's Fair Boulevard, along 230 acres (93 ha) on the east shore of Fountain Lake.[18]: 49 Despite the high-minded educational tone that Grover Whalen attempted to set, the Amusements Area was the most popular part of the Fair. The attractions included a roller coaster,[18]: 57 a Flying Turns-style bobsled,[18]: 53 a Life Savers-branded parachute tower called the Parachute Jump[18]: 57 [40] (later moved to Coney Island, where it is standing but not operating[41]), the 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge Gimbels Flyer train ride,[18]: 55 (later purchased by Kennywood, where it still runs today),[42] and carnival acts such as a "Little Miracle Town" with dwarves.[18]: 60 Other attractions included a "winter wonderland" called Sun Valley, a Theatre of Time and Space,[18]: 66 and a replica of Victoria Falls.[18]: 69–70

Frank Buck exhibited his "Frank Buck's Jungleland", which displayed rare birds, reptiles and wild animals along with Jiggs, a five-year-old trained orangutan.[18]: 57 In addition, Buck provided a trio of performing elephants, an 80-foot (24 m) "monkey mountain" with 600 monkeys, and an attraction that had been popular at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair: camel rides.[43] A number of the shows provided spectators with the opportunity of viewing women in very revealing costumes or topless, such as the "Frozen Alive Girl", the Living Pictures, and the Dream of Venus building. This last attraction was a pavilion designed by the Spanish surrealist artist Salvador Dalí which contained within it a number of unusual sculptures and statues as well as live nearly-nude performers posing as statues.[44][45] While there were a number of protests by prominent politicians over the course of the fair about the "low minded entertainment", and the New York Vice Squad raided shows in the area on several occasions, the public generally accepted this form of entertainment.[citation needed]

For the 1940 season, the area was rebranded as "The Great White Way".[46]

Bendix Lama Temple and nude show

The Bendix Lama Temple[47] was a 28,000-piece full-sized replica of the 1767 Potala temple in Rehe, Manchuria. It was commissioned and brought back by the industrialist and explorer Vincent Bendix.[48][49][50] The Temple had previously been exhibited at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair, called "Century of Progress".[51]

Attendance was disappointing in 1939. As a result, in 1940, a provocative show was added to the temple,[52] which detailed "the erotic temptations of a young Buddhist priest." The show involved multiple nude women.[53][54]

Aquacade

Billy Rose's Aquacade was a spectacular musical and water extravaganza foreshadowing the form of many popular Hollywood musicals in the ensuing years. The show was presented in a special amphitheater seating 10,000 people and included an orchestra to accompany the spectacular synchronized swimming performance. It featured Johnny Weissmuller and Eleanor Holm, two of the most celebrated swimmers of the era, and dazzled fairgoers with its lighting and cascades and curtains of water, pumped in waterfalls at 8,000 gallons a minute. The cost of admission was 80 cents.[18]: 52

The Aquacade facility itself served as an entertainment venue in the park for many years afterward, including the 1964–65 World's Fair, but fell into disrepair in the 1980s and was finally demolished in 1996.

Temple of Religion

William Church Osborn led an effort to construct a Temple of Religion, a modern building for the purpose of religious assemblies and production of plays, pageants, and concerts. The building included a 150-ft tower filled with stained glass windows.[55] Olin Downes was the general director of the World's Fair music department, and he selected Hugh Ross (director of the Schola Cantorum) to organize the vast series of recitals and concerts that were planned. John W. Hausermann funded the new Aeolian-Skinner pipe organ that was installed in the building.[56]

Standalone focal exhibits

There were two focal exhibits that were not located within any of the 1939 Fair's "zones". The first was Medical and Public Health Building, which was located on Constitution Mall and the Avenue of Patriots (immediately northeast of the Theme Center). This structure contained a massive "Hall of Man" dedicated to the human body, and a "Hall of Medical Science" dedicated to medical professions and devices.[18]: 168–173

The other was the Science and Education Building, located on a curved portion of Hamilton Place between the Avenue of Patriots and Washington Square, just north of the Medical and Public Health Building. The building was not used to teach science, but it contained an auditorium and several exhibits on science and education.[18]: 196–197

Themes

The colors blue and orange were chosen as the official colors of the fair, as they were the colors of New York City, and featured prominently.[citation needed]

Outdoor public lighting was at the time of a very limited and pedestrian nature, perhaps consisting of simple incandescent pole lamps in a city and nothing in the country. Electrification was still relatively new and had not reached everywhere in the US. The fair was the first public demonstration of several lighting technologies that became common in the following decades.[citation needed] These technologies included the introduction of the first fluorescent light and fixture. General Electric Corporation held the patent to the fluorescent light bulb at the time. Approximately a year later, the original three major corporations, Lightolier, Artcraft Fluorescent Lighting Corporation, and Globe Lighting, located mostly in the New York City region, began wide-scale manufacturing in the US of the fluorescent light fixture.[citation needed]

Another theme of the fair was the emerging new middle class, leading a hoped-for recovery from the Great Depression. The fair promoted the "Middleton Family"—Babs, Bud, and their parents—who appeared in ads showing them taking in the sights of the fair and the new products being manufactured to make life easier and affordable, such as the new automatic dishwasher.

Each day at the fair was a special theme day,[18]: 215–219 for which a special button was issued; for example, May 18, 1939, was "Asbury Park, New Jersey Day". Some of these buttons are very rare and all are considered collectibles.[citation needed]

Transportation

A special subway line, the Independent Subway System (IND) World's Fair Line, was built to serve the fair. World's Fair (now Mets–Willets Point) station on the IRT Flushing Line was rebuilt to handle fair traffic on the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) and Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit (BMT) systems. A Long Island Rail Road station (now Mets–Willets Point) was built next to the Flushing Line station. The IND extension departed the IND Queens Boulevard Line east of the Forest Hills–71st Avenue station and before the 75th Avenue station. The World's Fair station was at the east side of the Meadowlands at Horace Harding Boulevard. The period system route map and Fair maps display this temporary extension.[57] The World's Fair station was a terminus of the G train (alternate E trains also ran to World's Fair Station), and ran at ground level, separated from the Fair grounds by a fence, past the Jamaica Yard, which is still in use.[58]

For the 1939–40 Fair, a special fleet of 50 "World's Fair Steinway" cars were delivered in late 1938 by the St. Louis Car Company for Flushing Line service. Car #5655 survives in the New York Transit Museum fleet.

Closure and current status

The fair was open for two seasons, from April to October each year, and was officially closed permanently on October 27, 1940.[59] To get the fair's budget overruns under control before the 1940 season and to augment gate revenues, Whalen was replaced by banker Harvey Gibson. In addition, much greater emphasis was placed on the amusement features and less on the educational and uplifting exhibits. The great fair attracted over 45 million visitors and generated roughly $48 million in revenue. Since the Fair Corporation had invested 67 million dollars (in addition to nearly a hundred million dollars from other sources), it was a financial failure, and the corporation declared bankruptcy.[citation needed]

Many of the rides from the World's Fair were sold after its closure to Luna Park at Coney Island, which was allowed to call itself the New York World's Fair of 1941.[60] The Life Savers Parachute Jump was sold that same year and relocated to Steeplechase Park in Coney Island, where it was renamed the Parachute Jump.[41]

The Unisphere, built as the theme symbol for the 1964/1965 World's Fair, now stands on the site occupied by the Perisphere during the earlier Fair.

World War II

Although the United States did not enter World War II until the end of 1941, the fairgrounds served as a window into the troubles overseas. The pavilions of Poland and Czechoslovakia, for example, did not reopen for the 1940 season. Also on July 4 that same year, two New York City Police Department officers were killed by a blast while investigating a time bomb left at the British Pavilion.[61] The bombing has never been solved, but there is evidence that bombing was an inside job by William Stephenson, a British agent based in New York.[62]

Countries under the thumb of the Axis powers in Europe in 1940 like Poland, Czechoslovakia, and France ran their pavilions with a special nationalistic pride. The only major world power that did not participate for the 1939 season was Germany, citing budget pressures. The USSR Pavilion was dismantled after the first season, leaving an empty lot called "The American Commons". When the fair closed, many among the European staff were unable to return to their home countries, so they remained in the US and in some cases exercised a tremendous influence on American culture. For example, Henri Soulé moved from the French Pavilion at the fair to open Le Pavillon restaurant, retaining Pierre Franey as head chef.[63][64]

World War II presented additional problems with what to do with the exhibits on display in the pavilions of countries under Axis occupation. In the case of the Polish Pavilion, most of the items were sold by the Polish Government in exile in London to the Polish Museum of America and shipped to Chicago. A notable exception was made for a monument of the Polish–Lithuanian King Jagiełło to which Mayor Fiorello La Guardia took such a liking that he helped spearhead a campaign to have it installed in Central Park, where it still stands today.[65]

Belgian Pavilion

Another building saved from 1940 was the Belgian Building designed by Henry Van de Velde. It was awarded to Virginia Union University in Richmond, Virginia, and shipped to Richmond in 1941. The school still uses the building for its home basketball games.[66]

Bendix Lama Temple

After the Fair, the Temple was again disassembled, and placed in storage for many years. There were proposals to erect it at Oberlin College, Harvard University, Indiana University, and elsewhere, but they all failed for lack of funding. In 1984, the approximately 28,000 pieces were shipped to the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm, Sweden, with plans to rebuild it in a nearby park, but objections from the neighboring Chinese Embassy have stalled the project indefinitely.[49][50][67]

New York City Building

Some of the buildings from the 1939 fair were used for the first temporary headquarters of the United Nations from 1946 until it moved in 1951 to its permanent headquarters in Manhattan. The former New York City Building was used for the UN General Assembly during that time.[68] This building was later refurbished for the 1964 fair as the New York City Pavilion, featuring the Panorama of the City of New York, an enormous scale model of the entire city.[69] It became the home of the Queens Center for Art and Culture (later renamed the Queens Museum of Art, and now called the Queens Museum), which still houses and occasionally updates the Panorama.

One other structure from the 1939–40 Fair remains in original location: the New York City Subway's Mets–Willets Point station, rebuilt for the Fair. It also served the 1964–65 events and continues to serve New York Mets games and US Open Tennis.

Cultural references

The 1939 World's Fair made a strong impression on attendees and influenced a generation of Americans. Later generations have attempted to recapture the impression it made in fictional and artistic treatments.

Film and television

- Finale of the 1939 film Eternally Yours takes place in the fair

- In Walt Disney's Pinocchio (1940), the pool hall on Pleasure Island is shaped as an eight ball, with a cue next to it, a parody of the Trylon and Perisphere of the 1939 World's Fair.

- In the film Mr. & Mrs. Smith (1941), a comedy directed by Alfred Hitchcock, Carole Lombard and Gene Raymond visit the fair after a dinner date and find themselves stuck high in the air on the Parachute Jump when it malfunctions.

- The 1997 Pinky and the Brain episode "Mice Don't Dance" (3-11a) takes place in the 1939 World's Fair.

- The Twilight Zone Season 2 episode "The Odyssey of Flight 33" (1961) follows Flight 33 lost in time and briefly in 1939, with a sky view of the World's Fair. However, the pilot incorrectly identifies the location as Lake Success, which actually is in Nassau County, not Queens County.

- In The Simpsons 2003 episode "Brake My Wife, Please", Mr. Burns gives Homer a ticket to the fair as a reward for being the first employee to arrive at work that day. The ticket shown features the Trylon and Perisphere, as well as the opening and closing dates of the fair.

- In the 2011 film Captain America: The First Avenger, a very similar "World Exposition of Tomorrow" is featured at the same Flushing Meadows location, albeit in 1943, a year when no World Fair was held anywhere due to World War II.

- Batman: Mask of the Phantasm (1993) features “The World Of The Future” fair, Gotham City’s version. It provides inspiration for the Batmobile to Bruce Wayne, and later serves as a hideout for The Joker.

- TV show Futurama's namesake comes from the Futurama pavilion[70]

- In the 1992 film Forever Young, Nat (Elijah Wood) explains to Daniel (Mel Gibson) that what he is watching is called "television". Daniel replies to a disbelieving Nat, "I know, I saw it at the World's Fair in 1939."

- The X-files references the 1939 World Fair in season 2 episode 12

Literature

- E.B. White recounts a visit to the fair in his 1939 essay "The World of Tomorrow".[71]

- The still under-construction fair was the focus of the entire book The World's Fair Goblin (1939);

- DC Comics published a 1939 New York World's Fair Comics comic book, followed by a 1940 edition in the next year. It became the precursor of the long-running Superman/Batman team-up book World's Finest Comics.

- Doc Savage, a popular fictional character of the Pulp Era who used scientific detection in his adventures, was seen as a perfect match for the fair's "world of the future" concept. President Grover Whalen to do a Grand Opening cross promotion with the publisher, Street & Smith.[citation needed] The still under-construction fair appeared in the finale of The Giggling Ghosts (1938).[citation needed]

- In the novel The Nick of Time (1985) by George Alec Effinger, the main character travels through time to the fair and relives the same day over and over before he is rescued from the future.

- In the novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (2000) by Michael Chabon, one of the main characters breaks into the abandoned fairgrounds and the Perisphere.

- The fair is featured prominently in the graphic novel Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow? by Brian Fies. In it, a father takes his young son to the fair which inspires him to a lifelong fascination with the promise of a hopeful, wonder-filled future.[citation needed]

- Australian novelist and scriptwriter Frank Moorhouse places several chapters of his award-winning novel Dark Palace at the World's Fair. The novel's protagonist, Edith Campbell Berry, works for the League of Nations and in one episode she is presented as the driving force behind the flying of the League's flag alongside those of the United States and the State of New York.

- E.L. Doctorow's semi-autobiographic novel The World's Fair (1985) culminates with a lengthy description of a young boy's visit to the Fair.

- DC Comics' All-Star Squadron (1981–1987) started using the Perisphere and Trylon as the Squadron's base of operations starting in All-Star Squadron #21.

- Susie Orman Schnall's novel We Came Here to Shine (St. Martin's Press Griffin 2020) is historical fiction set at the 1939 World's Fair. The novel features two main characters: Vivi works as Aquabelle Number One in Billy Rose's Aquacade. Max is a journalist for the fair's daily paper, Today at the Fair.

Other

- Three French restaurants—La Caravelle, Le Pavillon, and La Côte Basque—were offshoots "of the seminal restaurant in the French pavilion of the 1939 New York World's Fair, where Charles Masson père began as a waiter under the eye of the legendary Henri Soulé".[72]

Archives

An archive of documents and films from the 1939 New York World's Fair is maintained at the New York Public Library (NYPL).[73]

In October 2010, the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. opened an exhibition titled Designing Tomorrow: America's World's Fairs of the 1930s.[74] This exhibition, which was available for view until September 2011, prominently featured the 1939 New York World's Fair.

See also

- Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations – 1853 World's Fair in Bryant Park, New York City

- List of world expositions

References

Notes

- ^ "1939 New York World's Fair". www.1939nyworldsfair.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

- ^ Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, p. 58, Random House, New York, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ^ Curtis, Adam. The Century of the Self, part 1 of 4.

- ^ Kuznick, Peter (September 1994). "Losing the World of Tomorrow: the Battle over the presentation of science at the 1939 World's Fair". American Quarterly. 46 (3): 341–73. doi:10.2307/2713269. JSTOR 2713269.

- ^ Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World 1996:404.

- ^ Brenner, Anita (April 10, 1938). "America creates American murals". New York Times Magazine: 10–11, 18–19.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot, "History of United States Naval Operations in World War II – Volume III: The Rising Sun in the Pacific 1931 – April 1942", Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1948, 1988, page 38.

- ^ a b Barnouw, E. (1990). Tube of plenty: The evolution of American television (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press

- ^ Westinghouse Electric Corporation (1938). The book of record of the time capsule of cupaloy, deemed capable of resisting the effects of time for five thousand years, preserving an account of universal achievements, embedded in the grounds of the New York World's fair, 1939. New York: Westinghouse Electric Corporation. OCLC 1447704. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ Westinghouse (Full Feature Documentary) on YouTube

- ^ Abbattista, Guido; Iannuzzi, Giulia (2016). "World Expositions as Time Machines: Two Views of the Visual Construction of Time between Anthropology and Futurama". World History Connected. 13 (3).

- ^ Franklin, H. Bruce (1982). "America as Science Fiction: 1939 (L'Amérique comme Science-Fiction: 1939)". Science Fiction Studies. 9 (1): 38–50. ISSN 0091-7729. JSTOR 4239455.

- ^ Simon Heffer, Vaughan Williams. Northeastern University Press (Boston, 2001), p. 98 (ISBN 1-55553-472-4).

- ^ Bliss, Sir A. (1939) Concerto for Piano and Orchestra. London: Novello and Company, Limited.

- ^ "Waylande Gregory: Art Deco Ceramics and the Atomic Impulse - University Museums - University of Richmond". Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2013.

- ^ "Vermeer's Masterpiece The Milkmaid". Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2009. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ^ Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 58–65, Random House, New York, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq Monaghan, Frank, ed. (1939). Official guide book of the New York World's Fair, 1939. Exposition Publications. OCLC 575567.

- ^ a b c d e f Cotter, B. (2009). The 1939–1940 New York World's Fair. Images of America. Arcadia Pub. ISBN 978-0-7385-6534-7. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ Barron, James (2017). The One-Cent Magenta, Inside the Quest to Own the Most Valuable Stamp in the World. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books. p. 167. ISBN 9781616205188.

- ^ "The Greek pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair". Markessinis, Andreas, (2013), p. 6

- ^ a b c Fortuna, James J. (December 17, 2019). "Fascism, National Socialism, and the 1939 New York World's Fair". Fascism. 8 (2): 179–218. doi:10.1163/22116257-00802008. ISSN 2211-6257.

- ^ Wood, Andrew F. (2004). New York's 1939-1940 World's Fair. Postcard history series. Arcadia Pub. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-7385-3585-2. OCLC 56796579. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Čapková, Helena, (2014)Transnational Networkers—Iwao and Michiko Yamawaki and the Formation of Japanese Modernist Design in Journal of Design History vol.27, no.4

- ^ "Netherlands – The Government Zone". 1939 New York World's Fair. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Martha Gil-Montero, Brazilian Bombshell (Donald Fine, Inc., 1989)

- ^ 1939 World's Fair Collection, Henry Madden Library Special Collections, California State University, Fresno

- ^ Steam locomotive Pm36-1 https://www.konstrukcjeinzynierskie.pl/wybor-redakcji/16-tematyka/historia/87-polska-myl-techniczna-na-expo39?showall=1

- ^ "När Dalahästen blev en svensk symbol i världen | Svensk Form" (in Swedish). Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ Ström, Marianne (1998). Metro-Art In The Metro-Polis. Paris: Art Creation Realisation. p. 96. ISBN 978-2-86770-068-2.

- ^ Porter, Russell B. (May 31, 1939). "U.S. Flag at Fair Tops Russia's Star; Unfurled Atop the Parachute Jump--Greatest Throng on a Weekday Present". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ "Boro Veterans Plan to Give Fair a Flagpole". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 31, 1939. p. 7. Retrieved July 14, 2019 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Russia Quits Fair; Finns to Stay; Reds to Raze $4,000,000 Pavilion; Moscow Orders Withdrawal Without Giving Explanation". The New York Times. December 2, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ "Big Carillon For Fair to be Built by Deagan" (PDF). The Diapason. 30 (2): 2. January 1, 1939.

- ^ "Stephen Foster CSO - Carillon". www.stephenfostercso.org. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 58–65, 338, 343, Random House, New York, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ^ "Bill of the Play: Railroads on Parade – A Pageant Drama of Transportation" (PDF). 1939nyworldsfair.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ^ "Coronation Scot – Trains on Display". Archived from the original on September 7, 2012.

- ^ Rogers, Colonel H.C.B. "The Last Steam Locomotive Engineer: R.A. Riddles", George Allen & Unwin, London 1970 ISBN 0-04-385053-7

- ^ "Play Area at Fair Takes On New Life; Amusement Zone Starts To Boom". The New York Times. May 28, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ a b "Steeplechase Park Highlights". Parachute Jump: NYC Parks. June 26, 1939. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ "39 NYWF legacy". The World's Fair Community.

- ^ "Frank Buck's Jungleland". Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ Schaffner, Ingrid, Photogr. by Eric Schaal (2002). Salvador Dalí's "Dream of Venus": the surrealist funhouse from the 1939 World's Fair (1. ed.). New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-56898-359-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Salvador Dalí's Dream of Venus". Louise Weinberg, Queens Museum

- ^ "'GREAT WHITE WAY' NEW FAIR FEATURE; Center of Fun in Amusement Zone to Be Brighter, More Colorful, Gibson Says 'PINWHEEL' LIGHT EFFECT Increasing Interest in the Exposition Reported by Publicity Chief". The New York Times. March 9, 1940. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "lama temple image". 1939nyworldsfair.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ^ [New York World's Fair/1939/1940 in 155 Photographs by Richard Wurts and Others (New York, Dover Publication, Inc. 1977), p. 137]

- ^ a b Roskam, Cole (Fall 2010). "The Golden Temple at Harvard" (PDF). Harvard-Yenching Institute Newsletter. harvard-yenching.org: 2–4. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ a b "Paint Schemes". Missionary Independent Spiritual Church. 1 (2). missionary-independent.org. June 9, 2006. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Appel, L. F. "The Bendix Lama Temple". Chicago World's Fair: A Century of Progress Exhibition 1933–1934. cityclicker.net. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ Coyle, Michael B. (July 5, 2021). Dawn of a New Day. The Wild Rose Press Inc. ISBN 978-1-5092-3608-4.

- ^ West, Chris (October 28, 2014). A History of America in Thirty-six Postage Stamps. Macmillan. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-250-04368-9.

- ^ "Bendix Lama Temple1". www.1939nyworldsfair.com. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ "The Temple of Religion, from the New York World's Fair series (PC225-6)". www.metmuseum.org. 1939. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ McAll, Reginald L. (February 1, 1939). "Great Church Music Program at Exposition" (PDF). The Diapason. 30 (3): 2.

- ^ "Reference at www.lib.berkeley.edu".

- ^ "The World's Fair Railroad". NYCSubway.org. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Alan (November 1, 2013). "The 1939 New York World's Fair". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ Charles J. Jacques, Hersheypark: The Sweetness of Success, Amusement Park Journal, 1997, page 78

- ^ "Police Die in Blast – Timed Device Explodes After It Is Taken Out of Pavilion". The New York Times. July 5, 1940. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Wortman, Marc (July 16, 2017). "Did Brits Kill New York City Cops to Get U.S. into WWII?". The Daily Beast – via www.thedailybeast.com.

- ^ "Restaurants: The King". Time. February 4, 1966. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ Franey, Pierre (October 18, 1989). "De Gustibus; Innocence Abroad: Memories of '39 Fair". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ "Quid plura? | "Moja droga, ja cię kocham ..."". November 24, 2008. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2009.

- ^ ""Virginia Union University – Belgium Building."". Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014. Virginia Union University, Belgium Building. Virginia Union University. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ^ Forêt, Philippe (2000). Chronology of Chengde. p. 161. ISBN 9780824822934. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "The Queens Museum of Art – New York City Building". Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ "The Panorama of the City of New York". Archived from the original on March 12, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2013.. Queens Museum. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ Taylor, Timothy Dean (2001). Strange Sounds: Music, Technology & Culture. pp. 104–105. ISBN 0-415-93684-5.

- ^ King, Steve (April 30, 2011). "White at the World's Fair". Barnesandnoble.com. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ Mimi Sheraton (December 24, 2007). "Check Please: The Frog at forty-Five". The New Yorker.

- ^ "World's Fair: Enter the world of tomorrow". Biblion: the boundless library. New York Public Library. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- ^ "Designing Tomorrow: America's World's Fairs of the 1930s". National Building Museum. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014.

Further reading

- James Mauro (2010). Twilight At The World of Tomorrow: Genius, Madness, Murder, and the 1939 World's Fair on the Brink of War. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-51214-7.

- World's Fairs on the Eve of War: Science, Technology, and Modernity, 1937–1942 by Robert H. Kargon and others, 2015, University of Pittsburgh Press

- Wright, Christopher C. (1986). "The U.S. Fleet at the New York World's Fair, 1939: Some Photographs from the Collection of the Late William H. Davis". Warship International. XXIII (3): 273–285. ISSN 0043-0374.

External links

- New York World's 1939–1940 records, 1935–1945 Manuscripts and Archives, New York Public Library.

- Official website of the BIE

- Tour of the 1939 World's Fair

- 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair Poster Stamps

- WNYC Broadcasts from the 1939-1940 New York World's Fair