Flag of Chile

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2007) |

| |

| La Estrella Solitaria (The Lone Star) | |

| Use | National flag and ensign |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 18 October 1817 |

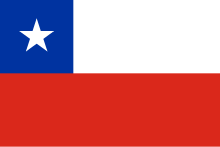

| Design | A horizontal bicolor of white and red with the blue square ended on the upper hoist-side corner of the white band bearing the white five-pointed star in the center. |

| Designed by | Ignacio Zenteno or Gregorio de Andía y Varela. |

| Presidential Standard | |

| |

| Design | Same design as the National Flag with the National Coat of Arms superimposed at the center. |

| Designed by | Alfonso Martinez Delpelao |

The flag of Chile consists of two equal-height horizontal bands of white and red, with a blue square the same height as the white band in the canton, which bears a white five-pointed star in the center. It was adopted on 18 October 1817. The Chilean flag is also known in Spanish as La Estrella Solitaria[1] (The Lone Star).

It has a 3:2 ratio between length and width, it is divided horizontally into two bands of equal height (the lower being red). The upper area is divided once: into a square (blue), with a single centered white star; and into a rectangle (white), whose lengths are in proportion 1:2. It is in the stars and stripes flag family.

The star represents Venus significant to the country's indigenous Mapuches[2] symbolizing a guide to progress and honor while other interpretations say it refers to an independent state; blue symbolizes the sky and the Pacific Ocean, white is for the snow-covered Andes, and red stands for the blood spilled to achieve independence.[3]

According to the epic poem La Araucana, the colours were derived from those from the flag flown by the Mapuche during the Arauco War. "Flag Day" is held each year on the ninth of July to commemorate the 77 soldiers who died in the 1882 Battle of La Concepción.

History of Chile

Pre-Independence flags

Flag possibly used by Mapuche troops during the early 18th century Arauco War.

Flag possibly used by Mapuche troops during the early 18th century Arauco War.The first records on the possible use of flags by indigenous peoples date back to the War of Arauco, the most famous being the use described in the late 16th-century epic poem La Araucana. In Canto XXI, Alonso de Ercilla described Talcahuano, warrior and chief of the Mapuche who work the lands near the present-day city that bears his name, bearing emblems of blue, white and red.

Two flags have been documented as used by Mapuche troops. However, these descriptions were made late in the eighteenth century without certainty about the age of them. One consisted of a five-pointed white star on a blue background similar to the canton of the current Chilean flag, while the second had a white eight-pointed star centered on a blue diamond with border zigzagged over a black background. The latter flag appears to be waved by the chief Lautaro in the best-known artistic representation of it, created by painter Pedro Subercaseaux.[4]

The main symbol of this flag is the star of Arauco, called guñelve, representing the flower of the canelo and the bright star of Venus. In the independence of Chile, Bernardo O'Higgins said that guñelve was the direct inspiration for creating the Chilean flag with the Lone Star.[2][5]

In the case of the colonizing troops, they used several Spanish flags. Each battalion had its own flag, which could incorporate different elements including the heraldic coat of arms of the King of Spain. One of the symbols most commonly used was the Cross of Burgundy, a jagged, red saltire crossed on a white cloth. The Cross of Burgundy was one of the main symbols of the Spanish Empire overseas, so it flew over the warships and was carried by the militia in the colonial territory during the Spanish colonization of the Americas.[citation needed]

In 1785, Carlos III established a uniform flag for all ships of the Spanish Armada, similar to the current flag of Spain. The use of this red-and-yellow flag would be extended in 1793 to "maritime towns, castles and coastal defenses." Despite the establishment of this new flag, the cross of Burgundy would still often used by colonial entities.[citation needed]

Flag of the Patria Vieja (1812–1814)

Flag of the Patria Vieja (1812–1814). First Chilean national flag, used by merchant ships.

Flag of the Patria Vieja (1812–1814). First Chilean national flag, used by merchant ships.At the onset of the Chilean War of Independence, the First Government Junta was proclaimed on 18 September 1810, marking Chile's first step toward independence. It would be during the government of Jose Miguel Carrera in which the desire for emancipation would gain more strength. Nevertheless, the junta was established (at least nominally) as a way of controlling the government during the absence of King Fernando VII, so that the symbols of government remained Hispanic. Therefore, one of the first acts of his government would be the implementation of national symbols, such as an insignia, a coat of arms and a distinctive flag to identify the patriots. The first flag, according to tradition, would have been embroidered by the sister of the ruler, Javiera Carrera, and would be presented and raised for the first time on 4 July 1812 at a dinner with the United States consul Joel Roberts Poinsett to celebrate the anniversary of U.S. independence, an event having a great influence on the locals' struggle for independence.

Named the flag of the Patria Vieja ("Old Fatherland"), the flag had three horizontal stripes of blue, white and yellow. For some, the bands represent the three branches of government: majesty popular, law and force, respectively; to others, the stripes represent features of nature: the sky, the snowy Andes and fields of golden wheat, respectively. The following 30 September, during a celebration in the capital to commemorate the first government junta, the Chilean coat of arms, also called Patria Vieja, was solemnly adopted and included in the center of the flag.

Although the blue-white-yellow flag of the Patria Vieja was the most recognized, other versions utilized a different arrangement of the colors, such as white-blue-yellow, for example. On other occasions, the red Cross of Santiago was included in the upper left corner together with the coat of arms in the center. The cross originates from the victory of the patriot troops in the Battle of El Roble, where within the possessions of the captured war booty was a distinctive insignia of the Order of St. James, an important symbol of Spanish pride.

In 1813 after the royalist invasion and the outbreak of the War of Independence, the Spanish symbols were abolished and the tricolor flag was formally adopted by the patriotic forces in a ceremony at the Plaza Mayor of Santiago. Months later in 1814, Carrera left political and military power, and Francisco de la Lastra was chosen as Supreme director. The war of independence began at great losses for the patriot side, and so signed the Treaty of Lircay on 3 May 1814. This agreement reaffirmed the Spanish sovereignty over the territory of Chile, among other things, and as one of its direct consequences, the Spanish flag was readopted at the expense of the tricolor.

The flag of the Patria Vieja would wave again after Carrera's return to power 23 July 1814 until the Battle of Rancagua (1–2 October) where the royalist victory ended the patriot government and began the Reconquista (or Reconquest) from 1814 to 1817, restoring the imperial standard. The tricolor flag was last flown for the last time in the Battle of Los Papeles (Batalla de los Papeles), but it would appear again raised in the ships that José Miguel Carrera brought in 1817 and during his campaigns in Argentina (1820–1821). The Reconquista ended with the victory of Liberation Army of the Andes (Ejército Liberatador de los Andes) in the Battle of Chacabuco on 12 February 1817. In this battle, the patriot troops fought with the army colonel and the flag of the Army of the Andes, inspired by the flag of Argentina, without readopting the blue-white-yellow standard.

Today, the flag of the Patria Vieja is used during memorial services for moose Chilean historical period, conducted by the National Institute (Instituto Nacional General José Miguel Carrera), which Carrera's government founded (10 August 1813). The emblem, adopted as a symbol at the beginning of carrerismo, was subsequently adopted by Chilean nationalism movement. For example, the flag with a red lightning bolt emblem superimposed was the insignia of the National Socialist Movement of Chile between 1932 and 1938.

Flag of the Transition (1817–1818)

Flag of the Transition (1817–1818).

Flag of the Transition (1817–1818).The victory at the Battle of Chacabuco on 26 May 1817 gave way to a new period known as the Patria Nueva (New Fatherland). A new flag was adopted that day, known today as the Flag of the Transition (Bandera de la Transición), and it is recognized as the first national flag and the last flag used until the one used currently. It was widely publicized at the time that the design was attributed to Juan Gregorio de Las Heras. This flag had three equal stripes: blue, white, and red, which is identical to the flag of pre-communist Yugoslavia. The bottom red strip replaced the yellow from the flag of 1812. The origin of the flag's colors would be based on the description given by Alonso de Ercilla as those of the insignia of the Mapuche troops. The significances of these colors were equivalent to those of the Patria Vieja, except that the yellow replaced the red to represent the blood that had been shed during the many conflicts.

Despite initial enthusiasm, the flag did not obtain official legalization and disappeared five months later. One reason for its suppression was that it was easily confused with both the flag of the Netherlands and the tricolor of revolutionary France, from which it was inspired.

According to the General History of Chile by Diego Barros Arana, the last time the Flag of the Transition was unfurled was at the ceremony to commemorate the Battle of Rancagua, two weeks before the adoption of the current national flag. However, there is information about a possible third flag between the Transitional and final, which would have exchanged the order of white and blue stripes and incorporated the five-pointed white star on the central strip, but that is no certainty, and it is not accepted by the majority of Chilean historians.

Third and current flag

Reproduction of the original design.

Reproduction of the original design.The design of the current Chilean flag is commonly attributed to Bernardo O'Higgins's Minister of War, José Ignacio Zenteno, having been designed by the Spanish soldier Antonio Arcos, although historians argue that it was Gregorio de Andía y Varela who drew it.

The flag was made official on 18 October 1817 by a decree,[6] of which only indirect references to the absence of a copy thereof, which was officially presented during the Pledge of Independence ceremony on 12 February 1818, a ceremony in which the bearer was Tomás Guido.

The original flag was designed according to the Golden Ratio, which is reflected in the relation between the widths of the white and blue parts of the flag, as well as several elements in blue canton. The star does not appear upright in the center of the rectangular canton, instead the upper point appears slightly inclined toward the pole in such a way that the projection of its sides divide the length of the canton golden proportion. Additionally, in the center is printed the National Coat of Arms, known from the previous Flag of the Transition and adopted in 1817.[7][8]

The adoption of the star configuration goes back to the star used by the Mapuches. According to O'Higgins, the star of the flag was the Star of Arauco. In Mapuche iconography, the morning star or Venus, (Mapudungun: Wünelfe or the Hispanicized Guñelve) was represented through the figure of an octagram star or a foliated cross. Although, the star which was finally adopted bore a star having five points with the design of the guñelve remaining reflected in an asterisk inserted in the center of the star, representing the combination of European and indigenous traditions.

Current Chilean flag.

Current Chilean flag.These designs soon fell into oblivion due to the difficulty in the flag's construction. So, the embroidered seal and the eight-pointed asterisk disappeared while the star was kept completely upright. In 1854 the proportion was determined in keeping with the colors of the flag, leaving the canton as a square and the ratio of hoist to fly set to 2:3. Finally, in 1912, the diameter of the star was established, the precedence of the colors in the presidential flag and decorative cockade was determined, setting the order as blue, white and red from top to bottom or from left to right of the viewer.

All of these arrangements would later be recast into Supreme Decree No. 1534 of 1967 from the Ministry of the Interior during the government of Eduardo Frei Montalva. In this document, the national emblems, coat of arms, the rosette or cockade, and the presidential standard were established. Meanwhile, the Political Constitution of Chile of 1980 establishes in the first clause of article 222 that all inhabitants of the republic should respect Chile and its national emblems.

Few records remain of the original design, the most valuable being that of the flag used in the Declaration of Independence, which had a width of two meters and a length just over two feet. The flag was protected by various hereditary institutions until it was stolen in 1980 by members of the Revolutionary Left Movement as a protest against the military dictatorship. This group kept the specimen and returned it in late 2003 to the National Historical Museum, where it can be found today.

There is a rather popular legend in Chile that claims this third Chilean flag won a "Most Beautiful National Flag in the World" contest. Its most common version states that this happened in 1907 in Blankenberge, Belgium, in the coast of the Baltic Sea [sic].[9] Other versions of this story say this happened in the 19th century, or that the Chilean flag was placed second after the French flag; there are even variations that talk about Chile's national anthem, placing it either in the first place or second, after La Marseillaise. The fact that the only documented version of this story gets basic details wrong (Belgium has a coast on the North Sea, not the Baltic Sea) doesn't reflect well on its historical accuracy.

Similar flags

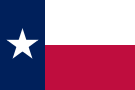

The flag of the U.S. state of Texas is similar to the Chilean flag. The flag of Texas was designed and adopted on 25 January 1839; whereas Chile adopted a flag similar to today's Chilean flag 22 years earlier on 18 October 1817.

Like Texas, on 17 January 1840; a coalition of nobles from the Mexican states of Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas advocated secession from Mexico to form their own federal republic called the Republic of the Rio Grande with Laredo (today part of Texas) as the capital but unlike Texas, was never formally recognized and ended on 6 November of the same year. Its flag was similar to that of Texas' in that there were three stars with a red hoist, and black and white bars on the side instead of one star with a blue hoist and white and red bars.

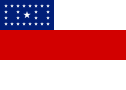

In 1822 during the Peruvian War of Independence, troops from both the Liberating Expedition of Peru (Expedición Libertadora del Perú) and the United Liberating Army of Peru (Ejército Unido Libertador del Perú) used a standard that was identical to the modern flag of Chile, except their flag had three stars in the canton, representing the three nations united by the cause of independence: the Argentine provinces, Chile and Peru.

On the other hand, the Chilean flag would have served as inspiration for the supporters of Cuban independence at the start the Ten Years' War in the so-called War Cry of Yara (Spanish: Grito de Yara) in 1868. The leader of this revolution, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, would have been inspired to create the first Cuban flag named La Demajagua in honor of the place where the revolt began. Two main differences are that the red and blue colors are inverted and that the red canton extends to the middle of the fly instead of one-third as on the Chilean flag.

Céspedes would have been inspired by the Chilean flag as a way of honoring the efforts of Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna on behalf of Chile to achieve independence of Cuba after the Spanish defeat in the Chincha Islands War.[10] According to Cespedes's son, his father "imagined a new flag that bore the same colors as that of the Carreras and O'Higgins and that would differentiate itself from the disposition of those colors."[11] However, the flag would not have much success, and an earlier design would become the definitive Cuban flag.

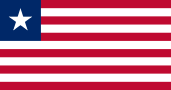

The flag of Liberia, founded in 1847, also includes a single star on the canton, but it has multiple horizontal stripes similar to the United States Flag.

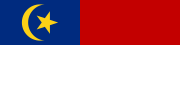

Also, the Flag of Malacca, a state in Malaysia, is similar, having the same colors (except the yellow star and moon) and a similar canton design, although the proportions and color order are different.

The state of Amazonas in Brazil also adopted a similar flag in 1982. Its flag also has an elongated blue canton with multiple stars.

The Catamarca province in Argentina adopted a flag in 2011 that has nearly the same colour design, but the blue is paler, and with a yellow border and a sun with two olive branches in the center.

-

Flag of Texas (1839)

-

Flag of the United States (1960)

-

Flag of the Liberating Expedition of Peru (1820)

-

Flag of Cuba used in the Ten Years' War (1868)

-

First flag of the Confederate States of America "Stars and Bars" (1861)

-

Flag of Liberia (1847)

-

Flag of the Czech Republic (1993), previously Czechoslovakia (1920–1992)

-

Flag of Yugoslavia (1918)

-

Flag of Poland (1980)

-

Flag of Catamarca province

-

Flag of Malaysia (1963)

-

Flag of Rapa Nui, Chile (until 1902)

Construction

The construction of the flag of Chile, at present, is officially defined in Supreme Decree No. 1,534 of the Ministry of the Interior, published in 1967, on the use of national emblems, which systematized and consolidated various laws and regulations on the subject. (Other laws include Law No. 2,597 of 11 January 1912, concerning the colors and proportions of the national flag, the presidential sash and rosette or cockade, and Supreme Decree No. 5805 of the Ministry of the Interior, published 26 August 1927, sets the size of the national flag for use in buildings and public offices.) According to the decree, the ratio between length and width of the flag is 3:2, being divided horizontally into two bands of equal size. While the lower section corresponds to the color red, the upper area is divided once in a blue square and a white rectangle whose lengths are in proportion 1:2, respectively. The star is located in the center of the blue canton and is constructed on a circle whose diameter is half the side of the canton.

Colours scheme

The exact color shades are not defined by law, but they are listed as "turqui blue", "white" and "red". Approximations below:

| Blue | Red | White | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGB | 0-57-166 | 213-43-30 | 255-255-255 |

| Hexadecimal | #0039a6 | #d52b1e | #FFFFFF |

| CMYK | 100, 66, 0, 35 | 0, 80, 86, 16 | 0, 0, 0, 0 |

Display

According to Chilean law, public use of the flag is allowed without prior authorization.[12] Before October 2011 its use was prohibited, without the approval of the provincial governor.[13][14] (An exception was made in 2010 during the bicentennial celebrations, where display of the flag was permitted during the whole month of September.[15]) This rule, however, was rarely enforced, as the flag was widely used on street celebrations, stadiums or rallies, without penal consequences.[citation needed]

Public buildings and private residences are required to display the flag on Navy Day (21 May), National Day (18 September) and Army Day (19 September).[14][16] If the flag is displayed incorrectly or not displayed at all during these days, the person responsible may be fined.[17]

On a pole

According to the protocol concerned, the flag should be hoisted from the tip of a white mast, and if done in company with other flags different, they must be of equal or lesser size. The Chilean flag must be set to the left if the sum of the flags is an even number or the center if the sum is an odd number. The flag must also be the first to be lifted and lowered the last.

Freely hanging

The Chilean flag can be displayed hanging either vertically or horizontally from a building or wall. In both cases, the blue square should be to the viewer's upper left.[14]

Respect due to the flag

Article 22 of the 1980 Constitution of Chile states that all inhabitants of the Republic owe respect to Chile and to its national emblems. The national emblems of Chile are the national flag, the coat of arms of the Republic and the national anthem. Pursuant to article 6 of the State Security Act of Chile (Decreto No. 890 de 1975), it is a felony against the public order to publicly mistreat the flag, the coat of arms, the name of the motherland or the national anthem.

Regional flags

Chile is administratively divided into 16 regions in which the internal government corresponds to the intendant. Some regional governments have adopted their own insignias, though most lack relevance, being principally used for public, regional organizations. The only exception is the flag of the Magallanes and Antartica Chilena Region, which has been adopted as a symbol of identity Magellan by its inhabitants.[18]

The regional flags can be found in the Access Hall of the National Congress of Chile in the city of Valparaíso. Many communes and cities also have their own flags.

-

Flag of the Arica and Parinacota Region

-

Flag of the Tarapacá Region

-

Flag of the Antofagasta Region

-

Flag of the Atacama Region

-

Flag of the Coquimbo Region

-

Flag of the Valparaíso Region

-

Flag of the Santiago Metropolitan Region

-

Flag of the O'Higgins Region

-

Flag of the Maule Region

-

Flag of the Ñuble Region

-

Flag of the Biobío Region

-

Flag of the Araucanía Region

-

Flag of the Los Ríos Region

-

Flag of the Los Lagos Region

-

Flag of the Aisén Region

Pledge to the National Flag

In memory of the brave heroes of the Battle of La Concepcion in 1882, on 9 July each year, the very day the final Chilean soldiers in La Concepcion died in defense of the Chilean nation, this Pledge to the Flag (Juramento de la Bandera) is recited at all installations and military bases of the Chilean Army and on graduation parades of the Chilean Navy and Chilean Air Force across the nation in remembrance of this moment in Chilean history. If done for the Carabineros de Chile, it is on the service anniversary (27 April) and passing out parades of enlisted personnel.

English translation of the pledge - Armed Forces variant

I (name and rank) pledge, to God and this flag,

to serve my country with loyalty,

whether in sea, on land, or anywhere else,

to give my life if need be,

to fulfill my military duties and obligations,

in accordance with the laws and regulations,

to obey quickly and punctually the orders of my superiors,

and thus invest my efforts in being a brave and honorable soldier (sailor, airman)

for the country's sake!

English translation of the pledge - Carabineros variant

I pledge, as a constable/second lieutenant, to God and this very flag,

To serve loyally the duties of my profession,

To preserve the Constitution and laws of the republic,

And to serve and protect all citizens and the people who live in this land

Even if it needs for me to sacrifice my life

For the defense of order and the country!

Gallery

-

Lautaro, painting by Pedro Subercaseaux.

-

Cross of Burgundy, emblem of the King and Armed Forces in Spanish Empire.

-

Flag of Crown of Castile.

-

Ancestral Araucanian Flag with the Guñelve, "the star of Arauco".

-

Naval ensign and national flag of Spain (1785–1873 and 1875–1931).

-

Possible flag used for a few days in 1817.

References

- ^ Claudio Navarro; Verónica Guajardo. "Símbolos: La Bandera" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- ^ a b Guaquil, Rodolfo Manzo. Los verdaderos emblemas de la República de Chile: 1810-2010 (in Spanish). p. 23.

Otro aspecto importante en la bandera es la estrella de cinco puntas e inclinada que representa a la wünelfe, nombre que con que los indígenas mapuches asignaban al planeta Venus...

- ^ "The CIA World Factbook". Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ "Virtual journal of contemporary art and emerging trends" (in Spanish). Escaner Cultural. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ^ Amunátegui Aldunate, Miguel Luis (1870). Los precursores de la independencia de Chile (in Spanish). Vol. III. Santiago, Chile: Imprenta, Litografía i Encuadernación Barcelona. pp. 587–590. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ Soublette, Gastón (1984). "Historia de los Emblemas Nacionales Chilenos. Hechos, mitos, errores y discusiones sobre los Símbolos Patrios" (in Spanish). soberaniachile.

- ^ Soublette, Gastón (1984). "La estrella de Chile" (in Spanish). Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso. Archived from the original on 22 September 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ Navas, Andrés (2015). "The amazing story of a forgotten golden flag" (PDF). Preprint. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2022.

- ^ "Chilean flag wins international competition (archived entry)" (in Spanish). 6 October 1907. Archived from the original on 2 August 2007. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Chile and the independence of Cuba II" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 5 April 2008.

- ^ Céspedes, Carlos Manuel de (1929). Las banderas de Yara y Bayamo (in Spanish). Paris.

imaginó una bandera nueva, que luciendo los mismos colores y forma de la de Carreras [sic] y O'Higgins se diferenciase de ésta en la disposición de aquellos

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Law 20,537, National Congress of Chile.

- ^ Article 4, letter f, Law 19,175, National Congress of Chile.

- ^ a b c "Decreto Supremo Nº 1534 de 1967 del Ministerio del Interior" (in Spanish). National Congress of Chile. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Decreto 2850 EXENTO de 24 de agosto de 2010, Ministerio del Interior de Chile.

- ^ "Decreto con Fuerza de Ley Nº 22 de 1959 del Ministerio del Hacienda" (in Spanish). National Congress of Chile. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ "ESTE 21 DE MAYO EL IZAMIENTO DEL PABELLON NACIONAL ES OBLIGATORIO". wordpress.com. 20 May 2010.

- ^ Suárez Pemjean, Rodrigo. "Mateo Martinic and Francisco Coloane: The construction of a regional identity in Magallanes" (in Spanish). Universidad de Chile. Archived from the original on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

External links

- Chile at Flags of the World

- Chile Historical Flag

- Sobre los verdaderos simbolos patrios de Chile simbolospatrios.cl