The Stranglers

The Stranglers | |

|---|---|

The Stranglers performing in Chicago in 2013 | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Guildford, Surrey, England |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1974–present |

| Labels | |

| Members | |

| Past members | |

| Website | www |

The Stranglers are an English rock band who emerged via the punk rock scene. Scoring 23 UK top 40 singles and 19 UK top 40 albums to date in a career spanning five decades, the Stranglers are one of the longest-surviving bands to have originated in the UK punk scene.

Formed as the Guildford Stranglers in Guildford, Surrey, in early 1974,[4] they originally built a following within the mid-1970s pub rock scene. While their aggressive, no-compromise attitude had them identified by the media with the emerging UK punk rock scene that followed, their idiosyncratic approach rarely followed any single musical genre, and the group went on to explore a variety of musical styles, from new wave, art rock and gothic rock through the sophisti-pop of some of their 1980s output. They had major mainstream success with their 1982 single "Golden Brown". Their other hits include "No More Heroes", "Peaches", "Always the Sun", "Skin Deep" and "Big Thing Coming".

The Stranglers' early sound was driven by Jean-Jacques Burnel's melodic bass, but also gave prominence to Dave Greenfield's keyboards. Their early music was also characterised by the growling vocals and sometimes misanthropic lyrics of both Burnel and Hugh Cornwell.[5] Over time, their output gradually grew more refined and sophisticated. Summing up their contribution to popular music, critic Dave Thompson later wrote: "From bad-mannered yobs to purveyors of supreme pop delicacies, the group was responsible for music that may have been ugly and might have been crude – but it was never, ever boring."[6]

Keyboard player Dave Greenfield died on 3 May 2020 after contracting COVID-19 while receiving treatment for a heart ailment.[7] The remaining band members completed a new album recorded with Greenfield, Dark Matters following his death and confirmed that they would proceed with their "Final Full UK Tour", initially announced in January 2020, in his honour.[8][9]

History

Formation and mainstream success (1974–1979)

Before forming the band, "Jet Black" (real name Brian Duffy) was in his mid-30s. A successful businessman, Black at one point owned a fleet of ice cream vans,[10] and later ran "The Jackpot",[11] a Guildford off-licence that would serve as the base for the early Stranglers.[12][13] Black had also been a semi-professional drummer in the late 1950s and early 1960s; after attaining a degree of financial stability due to his business successes, by 1974 he decided to return to drumming, and to assemble a band. The Stranglers came to be an influential band in the British punk and new wave scene of the mid-70s. Black drove the ice cream vans that would serve as the Stranglers' early tour buses.[14]

The group that eventually formed between 1974 and 1975 was originally named The Guildford Stranglers, but they soon dropped the geographical prefix and the name, The Stranglers, was registered as a business on 11 September 1974 by Black.[4][15] The other original personnel were bass player/vocalist Jean-Jacques Burnel, guitarist/vocalist Hugh Cornwell and keyboardist/guitarist Hans Wärmling, who was replaced by keyboardist Dave Greenfield within a year.[16] None of the band came from the Guildford area apart from Burnel, who was originally from Notting Hill but moved to Godalming during his childhood. Black is from Ilford, Cornwell from Kentish Town and Greenfield from Brighton, while Wärmling came from Gothenburg and returned there after leaving the band.

Cornwell was a blues musician before forming the band and had briefly been a bandmate of Richard Thompson,[17] Burnel had been a classical guitarist who had performed with symphony orchestras,[18] Black's musical background was as a jazz drummer,[19] and Dave Greenfield had played at military bases in Germany.[20] Their early influences included pre-punk psychedelic rock bands such as the Doors[21][22] and the Music Machine.

From 1976 the Stranglers became associated with the burgeoning punk rock movement, due in part to their opening for the first British tours of American punks the Ramones and Patti Smith.[23][24] Notwithstanding this association, some of the movement's champions in the British musical press viewed the band with suspicion on account of their age and musical virtuosity and the intellectual bent of some of their lyrics. However, Burnel was quoted saying, "I thought of myself as part of punk at the time because we were inhabiting the same flora and fauna ... I would like to think the Stranglers were more punk plus and then some."[25]

The band's early albums, Rattus Norvegicus, No More Heroes and Black and White, all released within a period of 13 months, were highly successful with the record-buying public and singles such as "Peaches", "Something Better Change" and "No More Heroes" became instant punk classics. Meanwhile, the band received a mixed reception from some critics because of their apparent sexist and racist innuendo. However, critic Dave Thompson argued that such criticism was oblivious to the satire and irony in the band's music, writing: "the Stranglers themselves revelled in an almost Monty Python-esque grasp of absurdity (and, in particular, the absurdities of modern 'men's talk')."[26] These albums went on to build a strong fan-following, but the group's confrontational attitude towards the press was increasingly problematic and triggered a severe backlash when Burnel, a martial arts enthusiast, punched music journalist Jon Savage during a promotional event.[27]

In February 1978 the Stranglers began a mini-tour, playing three secret pub gigs as a thank-you to those venues and their landlords for their support during the band's rise to success. The first was at The Duke of Lancaster in New Barnet on Valentine's Day,[28] with further performances at The Red Cow, Hammersmith, and The Nashville Rooms, West Kensington, in early September.[29]

During their appearance at the University of Surrey on the BBC TV programme Rock Goes to College on 19 October 1978, the group walked off stage because an agreement to make tickets available to non-university students had not been honoured.[30]

In the later half of the 1970s, the Stranglers toured Japan twice, joining the alternative music scene of Tokyo, which was evolving from the punk sound of Kyoto-based band Murahachibu (村八分, Ostracism), whose music influence spread to Tokyo in 1971. The Stranglers were the only foreign band to take part in a landmark scene focused around S-KEN Studio in Roppongi, and The Loft venues in Shinjuku and Shimokitazawa from 1977 to 1979.[31] The scene included bands such as Friction, and they became friends with the band, Red Lizard, who they invited back to London, where the band became known as Lizard.[32] In 1979, while still in Japan, Burnel also became close friends with Keith, co-founder and drummer for ARB. At the end of 1983, ARB's bassist was imprisoned, leaving the band with a problem for their forthcoming tour. Burnel took time out from the Stranglers to fly out to Japan at short notice and join ARB to cover the tour, including appearing at the 'All Japan Rock Festival' at Hibaya park, becoming the first non-Japanese to ever appear at the festival.[33][34][35] Burnel toured with ARB for 5 weeks and played on two studio tracks, "Yellow Blood" and "Fight it Out", both of which appeared on the RCA Victor ARB album Yellow Blood.[36]

Second phase (1979–1982)

In 1979, one of the Stranglers' two managers advised them to break up as he felt that the band had lost direction, but this idea was dismissed and they parted company with their management team.[37] Meanwhile, Burnel released an experimental solo album Euroman Cometh backed by a small UK tour and Cornwell recorded the album Nosferatu in collaboration with Robert Williams. Later that year the Stranglers released The Raven, which heralded a transition towards a more melodic and complex sound which appealed more to the album than the singles market. The songs on The Raven are multi-layered and musically complicated, and deal with such subjects as a Viking's lonely voyage, heroin addiction, genetic engineering, contemporary political events in Iran and Australia and extraterrestrial visitors, "Meninblack". The Raven saw a definite transition in the band's sound. The Hohner Cembalet – so prominent on the previous three albums – was dropped and Oberheim synthesizers used instead whilst acoustic piano was used on "Don't Bring Harry". A harmonizer was used to treat Burnel's vocal on the track "Meninblack", the recording of which led to Martin Rushent, who had produced their earlier albums, walking out leaving the band to co-produce the album themselves with Alan Winstanley.[38]

We're never going to use a producer again. They are just shitty little parasites. All they're good for is telling jokes. And we know better jokes than any of 'em.

The Raven was not released in the US; instead a compilation album The Stranglers IV was released in 1980, containing a selection of tracks from The Raven and a mix of earlier and later non-album tracks. The Raven sold well, reaching No.4 in the UK Albums Chart - it spawned one top 20 single, "Duchess", with "Nuclear Device" reaching No.36 and the EP "Don't Bring Harry" reaching No.41. This was followed by a non-album single, "Bear Cage", backed with "Shah Shah a Go Go" from The Raven. A 12-inch single, the band's first, containing extended mixes of both tracks was also released, but "Bear Cage" also only managed No.36 in the charts.

Following the success of the Stranglers' previous four albums they were given complete freedom for their next, The Gospel According to the Meninblack, a concept album exploring religion and the supposed connection between religious phenomena and extraterrestrial visitors. It was preceded by a single "Who Wants the World", which didn't appear on the album, and only just made the top 40. The album also included "Waltzinblack" which became adopted as a theme by TV chef Keith Floyd. The Gospel According to The Meninblack was very different from their earlier work and alienated many fans.[40] It peaked on the UK albums chart at No.8, their lowest placing to date, and in 1981 was widely considered an artistic and commercial failure.[40] The track "Two Sunspots" had been recorded during the Black And White sessions in 1978, but was shelved until 1980 when it was rediscovered and placed on The Gospel According to the Meninblack. The "Meninblack" track from The Raven is the "Two Sunspots" soundtrack slowed down.[38]

After a slow start, the Stranglers recovered their commercial and critical status with La Folie (1981) which was another concept album, this time exploring the subject of love. At first La Folie charted lower than any other Stranglers studio album, and the first single taken from it, "Let Me Introduce You to the Family", only charted at No.42. However, the next single was "Golden Brown". The song is an evocative waltz-time ballad, with an extra beat in the fourth bar. Cornwell said the lyrics were "about heroin and also about a girl. She was of Mediterranean origin and her skin was golden brown."[41] It became their biggest hit, charting at No.2 in the UK Singles Chart. It was also named as "record of the week" on BBC Radio 2, despite the station not previously playing music associated with the punk genre. It remains a radio staple to this day. Following this success, La Folie recharted at No.11 in the UK albums chart. "Tramp" was originally thought to be the ideal follow-up single to "Golden Brown"; however "La Folie" was chosen after Burnel convinced his bandmates of its potential.[42] Sung in French, it received negligible airplay and charted at No.47. Shortly afterwards the Stranglers left EMI. As part of their severance deal, the Stranglers were forced to release a greatest hits collection, The Collection 1977–1982.[43] The track listing for The Collection 1977–1982 included the new single "Strange Little Girl", which had originally been recorded on a demo in '74 and rejected by EMI. It became a hit, charting at No.7 in July 1982.

New label and sound (1983–1990)

Following the Stranglers' return to commercial success, many record companies lined up to sign them. Virgin Records was the most likely choice but Epic Records made a last minute offer and secured the Stranglers' services. The Stranglers once again had complete artistic freedom and in 1983 released their first album for Epic, Feline, which included the UK No. 9 hit "European Female". The album was another change in musical direction, this time influenced by European music. It was the first Stranglers album to feature acoustic guitars, and it was on this album that Jet Black began to use electronic drum kits.[44] Hugh Cornwell stated, "On La Folie there were three tracks – 'Golden Brown' ... 'La Folie' and 'How to Find True Love and Happiness in the Present Day' – that sort of pointed us away from what we had been doing. It was strange doing those tracks, because we'd never really attempted that quite minimalistic recording technique. And when we started writing for Feline, things were coming out the same way."[45] The album gained much critical success but fell well short of La Folie in terms of sales and failed to produce another hit after "European Female". Nonetheless Feline broke the Stranglers in Europe and reached No.4 in the UK chart in January 1983.

1984 saw the release of Aural Sculpture which consolidated the band's success in Europe and established them in Oceania. It included the UK No.15 hit "Skin Deep" (which also reached No. 11 in Australia and No. 19 in New Zealand, and Top 30 in the Netherlands). This was their first album to feature the three-piece horn-section which was retained in all their subsequent albums and live performances until Hugh Cornwell's departure in 1990. Aural Sculpture was only a moderate success in the UK album charts, peaking at No.14 in November 1984.

Their 1986 album, Dreamtime, dealt with environmental concerns among other issues. Its signature track, and another radio staple for many years to come, was "Always the Sun" (a No.15 hit in France and No.16 hit in Ireland, No.21 in Australia, No.30 in the UK, and No.42 in the Netherlands). The only Stranglers album to chart in the US, Dreamtime was again only a moderate hit in the UK, reaching No. 16 in November 1986.

The Stranglers' final album with Cornwell, 10, was released in 1990. This was recorded with the intention of building on their "cult" status in America. Following the success of their cover of The Kinks' "All Day and All of the Night", a UK No. 7 hit in 1988, the Stranglers released another '60s cover, "96 Tears" as their first single from 10; it reached No. 17 in the UK. Despite this success, the follow-up single "Sweet Smell of Success" only reached No.65. "Man of the Earth", which the band had high hopes for, was due to be the third single from the album, but Epic Records decided against it. In August 1990, Hugh Cornwell abruptly left Stranglers to pursue a solo career, following the band's failure to attain a tour in the US.[46] In his autobiography, Cornwell stated that he felt that the Stranglers were a spent force creatively, and cited various examples of his increasingly acrimonious relationship with his fellow band-members, particularly Burnel.

Post-Cornwell era (1990s)

Following the departure of Cornwell, CBS-Sony dropped the Stranglers from their roster. The remaining members recruited John Ellis, who had had a long-standing association with the band. He had opened for them in the 1970s as a member of The Vibrators, filled in for Cornwell during his time in prison for drug possession in 1980, worked with Burnel and Greenfield in their side-project Purple Helmets, and been added to the Stranglers' line-up as a touring guitarist a short time before Cornwell's departure. Burnel and Ellis briefly took over vocal duties (for one television appearance on The Word) before enlisting Paul Roberts, who sang on most songs live, even those originally sung by Burnel.

This line-up recorded four albums: Stranglers in the Night (1992), About Time (1995), Written in Red (1997) and Coup de Grace (1998).

2000s resurgence and reversion to a four-piece

In 2000, Ellis left the band and a new guitarist, Baz Warne, was recruited.

The Stranglers achieved something of a critical and popular renaissance in 2004[47][48] with the album Norfolk Coast and a subsequent sell-out tour, together with their first Top-40 hit (No. 31 UK) in fourteen years, "Big Thing Coming". The album also included Tuckers Grave about a Somerset cider house named after the victim of a suicide in a nearby farm which members of the band now occupied. In 2005, Coast to Coast: Live on Tour was released, the live album contained songs recorded during their tour the previous year. On their sellout UK tour they were supported by Goldblade.

In May 2006, Roberts left the band, and the Stranglers were now back to a four-piece line-up: Burnel, Black, Greenfield and Warne, with the lead vocals shared between Warne and Burnel. In concert, Burnel returned to singing the songs he originally recorded as lead vocalist, and Warne sang the numbers originally led by Hugh Cornwell.

Suite XVI, the follow-up album to Norfolk Coast, was released in September 2006 (the title is a pun on "Sweet 16" and also a reference to the fact that it was the band's sixteenth studio album) and continued the band's resurgence. Although partly a return to the band's heavier punk roots, the album featured a typically idiosyncratic mixture of musical styles which included a country and western style Johnny Cash pastiche/homage "I Hate You".

In 2007 it was reported that drummer Black was suffering from atrial fibrillation, an ailment which subsequently forced him to miss a number of shows, particularly where extended travel was required. On such occasions Ian Barnard, Black's drum technician, deputised.[49]

On 4 November 2007, the band (with Black) played a sell-out gig at the Roundhouse in Camden, North London, marking the thirtieth anniversary of their headline run at the same venue in 1977. The set list was the same as the 1977 concert, with the addition of a couple of more recent songs as a final encore. The event is recorded on the DVD Rattus at the Roundhouse.[50]

2010–present

The Stranglers continued their resurgence in 2010 starting with an extensive UK tour, including a sold-out return to the Hammersmith Apollo in March, their first visit there since 1987. They were supported on the 16-date UK tour by Max Raptor.[51]

A double CD compilation album, Decades Apart, containing a selection of tracks from the full career of the band, including at least one from each of their sixteen studio albums and two new tracks, "Retro Rockets" and "I Don't See the World Like You Do", was released in February 2010. The download version of Decades Apart included an unreleased recording from 1978, "Wasting Time", inspired by the band's 'Rock Goes To College' experience earlier that year;[30] this track, originally titled "Social Secs" was never released, and the music ended up being reversed and released as "Yellowcake UF6", the B-side to "Nuclear Device" in 1979.

Across the summer the band played a number of festivals, including Weyfest and Glastonbury and T in the Park in the UK and Oxegen 2010 in Ireland, and concerts in Japan, Greece, Poland, Slovakia and Bulgaria. The band also released a new live album and DVD, recorded at the Hammersmith Apollo in May 2010.[51] In March 2011, the band completed another UK tour. Burnel's long-term friend, Wilko Johnson, was invited to bring The Wilko Johnson band on the tour. In April, the band began touring Europe, with many gigs and major festivals lined up for the entire year.

On 23 September 2012, the band returned to Looe, Cornwall, fronted by Warne and Burnel. The band had originally spent time in Looe writing Suite XVI.[52]

Giants was released in 2012, including the first instrumental on an album since "Waltzinblack" on The Gospel According to The Meninblack. The "deluxe" version consisted of a second disc containing tracks from the 'Weekend in Black' acoustic session in November 2011.

2013 saw the band play a full UK tour, with Black playing the second half at most gigs (Jim Macaulay taking the first half).[53] Several festivals were booked for 2013, including a session at the BBC Proms on 12 August. For the North American tour Black was not present, with Macaulay playing the entire show.[54][55]

In 2014, the band celebrated their fortieth birthday with a Ruby Tour, throughout the UK and Europe. In 2015, the March On tour had 18 dates around the United Kingdom. Where stage space allowed, a second drum kit was set up and Jet Black appeared for a set of four songs. A proposed gig in Moscow was announced and then cancelled due to visa difficulties, but a mini-tour of the UK took place in July. The band then played gigs throughout Europe, ending in November. In April 2016, they returned to New Zealand and Australia.[56]

Black ceased performing on stage with the band after some partial-set appearances in March 2015, although he remained an official member of the band until his retirement was confirmed in 2018.[57] Jim Macaulay appeared in a promotional photograph alongside Burnel, Greenfield and Warne for the first time in 2016 and has since been named as an official member of the group.

In August 2017, the Stranglers performed at an outdoor concert in Hull as part of the UK City of Culture celebrations. In July 2018, the band played at the LUNAR festival in Tanworth-in-Arden.

During an interview with Janice Long, on BBC Radio Wales, on 10 July 2018, Burnel revealed that Black continued to be in fairly poor health and had suffered a minor stroke earlier in 2018.

Greenfield died on 3 May 2020, at the age of 71. He had contracted COVID-19 while in hospital for a heart ailment.[58] The band's eighteenth studio album Dark Matters, features contributions from Greenfield and is also their first release following the retirement of Jet Black.[57] It was released on 10 September 2021,[59] and entered the UK album chart at number 4, the highest position since Feline in 1983 and their first top 10 position since 1990.[60]

In November 2021, the band began their last full tour with their new keyboard player, Toby Hounsham, who played with Rialto, an English rock band formed in London in 1997, and subsequently Mungo Jerry for live and studio work since the early 2000s. The tour is currently scheduled to continue through the UK and several European countries, ending in Sweden in October 2022.

After many years of health problems, Black died on 6 December 2022 at the age of 84.[61]

Legacy

"No More Heroes" was featured in the first episode of the BBC series Ashes to Ashes and in the third episode of the second season of the American TV show Queer as Folk.[62] The title was used for the 2007 video game No More Heroes, created by Japanese designer Goichi Suda,[63] who is also a fan of the band.[64] Despite the name, the cost of licensing the track prevented the song from appearing in the game.[64] A cover version by Violent Femmes was used for the film Mystery Men.

The song "Let me Down Easy" was used as the opening credits theme for Hardcore Henry. "Peaches" appeared in the title sequence of Sexy Beast by director Jonathan Glazer, and was used as the closing theme for many of Keith Floyd's cooking programmes, with the instrumental track 'Waltzinblack' providing the title music.

"Golden Brown" featured in Guy Ritchie's film Snatch (2000), was used extensively in the Australian film He Died with a Felafel in His Hand. It also featured in the Black Mirror episode "Metalhead"[65] and in Season 2 of The Umbrella Academy.[citation needed]

Tori Amos covered "Strange Little Girl" on her 2001 Strange Little Girls album.[66]

Members

Current members

- Jean-Jacques Burnel – bass, backing vocals (1974–present), lead vocals (1974–1990, 2006–present)

- Baz Warne – guitar, backing vocals (2000–present), lead vocals (2006–present)

- Jim Macaulay – drums, percussion, backing vocals (2018–present, touring musician: 2012–2018)[67][68]

- Toby Hounsham – keyboards, backing vocals (2021–present)

Former members

- Jet Black – drums, percussion (1974–2018; semi-retired from touring 2007–2018; died 2022)[69]

- Hugh Cornwell – lead and backing vocals, guitar (1974–1990)

- Hans Wärmling – keyboards, backing vocals, guitar (1974–1975; died 1995)

- Dave Greenfield – keyboards, backing and lead vocals (1975–2020; died 2020)

- John Ellis – guitar, backing vocals (1990–2000)

- Paul Roberts – lead vocals (1990–2006)

Former touring musicians

- Ian Barnard – drums, percussion (2007–2012)

(In the late 1980s, the Stranglers regularly featured a 3-piece brass section in their live line-up.)

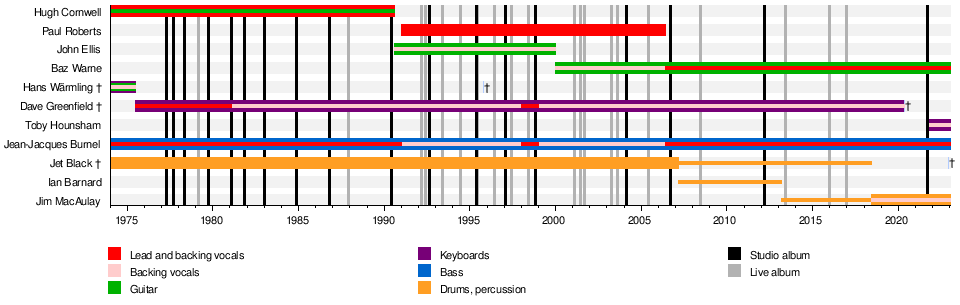

Timeline

Discography

- Rattus Norvegicus (1977)

- No More Heroes (1977)

- Black and White (1978)

- Live (X Cert) (live, 1979)

- The Raven (1979)

- The Gospel According to the Meninblack (1981)

- La Folie (1981)

- Feline (1983)

- Aural Sculpture (1984)

- Dreamtime (1986)

- All Live and All of the Night (live, 1988)

- 10 (1990)

- Stranglers in the Night (1992)

- About Time (1995)

- Written in Red (1997)

- Coup de Grace (1998)

- Norfolk Coast (2004)

- Suite XVI (2006)

- Giants (2012)

- Dark Matters (2021)

References

- ^ Cartwright, Garth (17 May 2020). "Dave Greenfield: Keyboardist Who Defined the Sound of the Stranglers". The Independent. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b Hughes, Rob (6 May 2020). "The Stranglers: A Guide to Their Best Album". Louder Sound. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Dark Matters". Stranglers Official Online Store. TM Stores. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

Surviving Stranglers band members, JJ Burnel, Baz Warne and newest member Jim Macaulay completed Dark Matters remotely during lockdowns, making it their first album since 2012.

- ^ a b Buckley 1997, p. 23.

- ^ Hasted, Nick (6 November 2007), "The Stranglers, Roundhouse, London", The Independent

- ^ Thompson, Dave. "Biography" (DLL). The Stranglers. allmusic. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ "Stranglers Official Site › David Paul Greenfield (29/3/49-3/5/20)". www.thestranglers.co.uk.

- ^ "Stranglers Official Site › UK tour autumn/winter 2020". www.thestranglers.co.uk. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "Stranglers Official Site › Full Final UK Tour And Album Update". www.thestranglers.co.uk.

- ^ Western Mail (Cardiff, Wales) – The Stranglers.(News)

- ^ The Stranglers prepare for Weyfest Archived 4 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine – GetReading.co.uk

- ^ Virgin Radio – Stranglers biography

- ^ TRIBUTE – THE STRANGLERS: The stranglers' timeline.(Chronology) – Music Week

- ^ The Stranglers on 40 years of fights, drugs, UFOs and 'doing all the wrong things' - The Guardian. 12 March 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "'74-'14: Forty years in photos-part 1". Stranglers Official Site. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ Buckley 1997, p. 28.

- ^ Buckley 1997, p. 11.

- ^ Buckley 1997, p. 16.

- ^ Buckley 1997, p. 7.

- ^ Buckley 1997, p. 30.

- ^ "Jean-Jacques Burnel of the Stranglers on the Songs That Changed His Life". Nzherald.co.nz. 13 February 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ "Music – Review of the Stranglers – Rattus Norvegicus". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Buckley 1997, p. 46.

- ^ Buckley 1997, p. 49.

- ^ "JJ Burnel Stranglers Interview Pt2 – Punk Rock". Punk77. 2005. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ^ Thompson, Dave. "The Stranglers' biography at allmusic.com". Retrieved 10 September 2006.

- ^ Buckley 1997, p. 99.

- ^ "Stranglers Official Site". Stranglers.net. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ "Stranglers Live Performances 1974–1990". Xulucomics.com. 12 August 1990. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ^ a b "The Stranglers: Rock Goes To College". Swewr.uklinux.net. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 21 April 2006.

- ^ "マガジン". Bounce.com. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ "V.A.(PUNK) : <パンクロックの封印を解く>"東京ロッカーズ"の全貌に迫る『ROCKERS[完全版]』 / BARKS ニュース". Barks.jp. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ Strangled Vol.2 No.18 – June 1984

- ^ "HA・GA・KU・RE ・ ARB with J・J BURNEL(The Stranglers)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ "無題ドキュメント". Arb-tamashii.com. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ Strangled. Vol: 2. No.: 21. June 1985

- ^ Buckley 1997, p. 135.

- ^ a b Cornwell & Drury 2001, p. 131.

- ^ Tobler, John (1992). NME Rock 'N' Roll Years (1st ed.). London: Reed International Books Ltd. p. 332. CN 5585.

- ^ a b Buckley 1997, p. 174.

- ^ Cornwell & Drury 2001, p. 215.

- ^ Cornwell & Drury 2001, p. 223.

- ^ Cornwell & Drury 2001, p. 217.

- ^ Cornwell & Drury 2001, p. 227.

- ^ Burton, Nick (June 1983). "Lean and Hungry Stranglers Protest the High-Tech Age". Record. 2 (8): 8.

- ^ Cornwell, Hugh (2005). A Multitude of Sins. Harper Collins. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-00733356-1.

- ^ Peacock, Tim. "The Old Testament: The UA Studio Recordings 1977-1982". Record Collector. Diamond Publishing. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Kelly, Ian. "The Stranglers, Salisbury City Hall". The Daily Echo. Newsquest Media. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ "SIS News Archive – A Message from Jet Black". Stranglers.net. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "SIS News Archive". Stranglers.net. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ a b "SIS News". Stranglers.net. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ "SIS News". Stranglers.net. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ Hutchinson, Martin (1 April 2013). "Live Review: The Stranglers – Manchester Academy – 30/3/2013". The Bolton News. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ "Summer Drummer". thestranglers.net. 19 June 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ Goldsmith, Belinda (24 April 2013). "Stranglers break out of punk mould with classical and ballet". Reuters. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ Walter Marsh (26 August 2015). "The Stranglers announce 2016 Australian tour". Rip It Up. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ a b Robb, John (11 August 2021). "The Stranglers: Dark Matters – album review". Louder Than War. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

It's been a long time since we heard any new material and the album has been overshadowed by the death of core band member Dave Greenfield and his genius keys, and the final retirement of the great Jet Black but the record has been worth the wait.

- ^ "Stranglers keyboard player dies with coronavirus". BBC News. 4 May 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "Dark Matters". The Stranglers. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Copsey, Rob. "Manic Street Preachers win "titanic battle" against Steps to claim second Number 1 on Official Albums Chart". Official Charts. The Official UK Charts Company. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "The Stranglers drummer Jet Black dies after 'years of ill health' aged 84". The Guardian. 8 December 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ "Queer as Folk Music". Princessofbabylon.com. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Boyes, Emma. "Q&A: SUDA-51 on No More Heroes". Gamespot. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ a b "The Bizarre and Brilliant Video Game World of Goichi Suda". Eight And A Half Bit. Eight And A Half Bit. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ Hooton, Christopher; Stolworthy, Jacob (30 December 2017). "Netflix's Black Mirror season 4: Every episode ranked". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine (18 September 2001). "Strange Little Girls – Tori Amos | Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ Carne, Owen (19 June 2012). "News: Summer drummer…". thestranglers.co.uk. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ "Jim Macaulay: Biog". jimmacaulaydrums.com. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Nerssessian, Joe. "The Stranglers: All the things we did that were frowned upon in the past now seem like badges of honour". Belfasttelegraph. Mediahuis. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

Sources

- Cornwell, Hugh; Drury, Jim (2001). The Stranglers: Song by Song. Sanctuary Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-86074-362-5.

- Buckley, David (1997). No Mercy: The Authorised and Uncensored Biography of The Stranglers. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-68062-9.

External links

- Official Site

- The Stranglers discography at Discogs

- The Stranglers at IMDb

- The Stranglers

- A&M Records artists

- Castle Communications artists

- EMI Records artists

- English new wave musical groups

- English punk rock groups

- Epic Records artists

- Liberty Records artists

- Musical groups established in 1974

- Musical groups from London

- British pub rock music groups

- English post-punk music groups

- Stiff Records artists

- United Artists Records artists