The Cradle Will Rock

| The Cradle Will Rock | |

|---|---|

First edition 1938 | |

| Music | Marc Blitzstein |

| Lyrics | Marc Blitzstein |

| Book | Marc Blitzstein |

| Productions | 1937 Broadway 1947 Broadway revival 1964 Off-Broadway revival 1983 Off-Broadway revival 1985 West End |

The Cradle Will Rock is a 1937 play in music by Marc Blitzstein. Originally a part of the Federal Theatre Project, it was directed by Orson Welles and produced by John Houseman. Set in Steeltown, U.S.A., the Brechtian allegory of corruption and corporate greed includes a panoply of social figures. It follows the efforts of Larry Foreman to unionize the town's workers and combat the powerful industrialist Mr. Mister, who controls the town's factory, press, church, and social organization. The piece is almost entirely sung-through, giving it many operatic qualities, although Blitzstein included popular song styles of the time.

The WPA temporarily shut down the project a few days before it was to open on Broadway. To avoid government and union restrictions, the show was performed on June 16, 1937, with Blitzstein playing piano onstage and the cast members singing their parts from the audience.[1]

The original cast consisted of John Adair, Guido Alexander, Marc Blitzstein, Peggy Coudray, Howard da Silva, George Fairchild, Robert Farnsworth, Edward Fuller, Will Geer, Maynard Holmes, Frank Marvel, Charles Niemeyer, Le Roi Operti, Jules Schmidt, George Smithfield, Olive Stanton, and Bert Weston.[2]

The Cradle Will Rock was reprised January–April 1938 as part of the first season of the Mercury Theatre, an independent repertory company founded by Welles and Houseman. An abridged version of the production was recorded and released in 1938, the first original cast recording ever made.

History

He was an engine, a rocket, directed in one direction which was his opera—which he almost believed had only to be performed to start the Revolution. You can't imagine how simple he was about it.

— Orson Welles[3]: 130

The Cradle Will Rock had its genesis in composer Marc Blitzstein's Sketch No. 1,[4]: 105 a short work that garnered positive comment in the Daily Worker after it was performed at The New School in February 1936.[4]: 155–156 "It had to do with a Moll, a Gent, a Dick; the plot concerned a little proposition and a little chicanery", Blitzstein later recalled.[5]: 218 Bertolt Brecht had heard the sketch at Blitzstein's apartment in late 1935, and suggested that he expand its theme from literal to figurative prostitution. Blitzstein remembered him as saying, "There is prostitution for gain in so many walks of life: the artist, the preacher, the doctor, the lawyer, the newspaper editor. Why don't you put them against this scene of literal selling." Blitzstein took up the idea and ultimately dedicated The Cradle Will Rock to Brecht.[4]: 157

With revisions, the streetwalker scene in Sketch No. 1 became the first of the ten scenes in Blitzstein's opera The Cradle Will Rock, while its song, "Nickel Under the Foot", moved to scene seven. Blitzstein borrowed from a number of his other earlier works as well, which blunts the common notion that Kurt Weill and Hanns Eisler were undue influences.[4]: 168 Blitzstein objected to the terms operetta and musical comedy, and deliberately called the work an opera—a form in which drama and music have "a continuous and serious mutual relation".[4]: 169

"I wrote both the words and the music of The Cradle Will Rock at white heat during five weeks in 1936," Blitzstein said,[6] "as a kind of rebound from my wife's death in May." The drafted short score was completed September 2, 1936.[4]: 157 Blitzstein signed with the William Morris Agency and began auditioning The Cradle Will Rock in one-man shows in the homes of New York producers including Herman Shumlin,[4]: 175 Harold Clurman for the Group Theatre, Charles Friedman for the Theatre Union, and Martin Gabel.[7]: 246

In the fall of 1936, Blitzstein attended a performance of the Federal Theatre Project 891 farce Horse Eats Hat and went backstage to meet the show's writer-director, 21-year-old Orson Welles. He found a chance to play his opera for Welles,[4]: 175 who was won over by Blitzstein's enthusiasm and endearing faith in his unproduced musical. A deep friendship began between them.[8]: 385 [9]: 288

Welles thought about directing The Cradle Will Rock for the Theatre Guild, which was a long shot;[4]: 171 and he was set to direct it for the Actors Repertory Company, which optioned the work but later had to withdraw from the agreement for lack of finances.[10]: 137 [4]: 175 Rivalries and resentments were always in play between Welles and John Houseman, producer of Federal Theatre Project 891,[8]: 385 as Houseman frankly expressed in his memoirs:

I remember listening jealously, with an ill-concealed sense of rejection, to Orson's enthusiastic comments about the piece (which I had not heard) and to his ideas for casting and staging it, which he elaborated for my annoyance. ... In the midst of our doldrums and as part of the complicated game of one-upmanship that Orson and I were constantly playing together, I suggested one night in his dressing room that if I were ever invited to hear Marc's work, I might conceivably find it suitable for production at the Maxine Elliott for Project 891.[7]: 246

Welles arranged for Blitzstein to play his opera through for him,[4]: 171 and Houseman was convinced that it should be presented by the Federal Theatre Project.[10]: 137

That view was supported at the highest level. Hallie Flanagan, national director of the Federal Theatre Project, was invited to a dinner party March 1, 1937,[5]: 223 at the apartment Houseman shared with composer Virgil Thomson. Blitzstein auditioned his opera for Flanagan—this time supported by the strident voice of Howard da Silva, an actor Welles knew from his radio work who had also led the Federal Theatre Project in his native Cleveland.[10]: 137 [8]: 386

"Marc Blitzstein sat down at the piano and played, sang, and acted," Flanagan recalled, "with the hard hypnotic drive which came to be familiar to audiences, his new opera":

It took no wizardry to see that this was not a play set to music, nor music illustrated by actors, but music + play equaling something new and better than either. This was in its percussive as well as its verbal beat Steeltown, U.S.A.: street corner, mission, lawn of Mr. Mister, drugstore, hotel lobby, faculty room, night court: America, 1937.[11]: 201

Blitzstein wrote his sister: "Hallie F. is nuts about the work—but just as terrified of it."[4]: 172

The Federal Theatre Project's greenlighting of The Cradle Will Rock coincided with one of the most violent strikes of the 1930s. In March 1937, U.S. Steel signed a historic collective bargaining agreement with the steelworkers union. Even though the Supreme Court had affirmed the constitutionality of the Wagner Act in April, smaller steel manufacturers refused to sign a similar agreement with workers,[10]: 136 setting off a five-month strike that reached a crescendo with the 1937 Memorial Day massacre at the Republic Steel Corporation in Chicago.

Flanagan's attention was absorbed by "the thunder and lightning surrounding the project itself. For the order to cut was rumored again. The Act of Congress under which we were set up was to expire on June 30."[11]: 201 Conservative elements in Congress already thought little of the Federal Theatre Project, and a government-sponsored pro-union Broadway show would exacerbate those resentments.[3]: 133

Synopsis

The story is set in Steeltown, U.S.A., on the evening of a union drive.

Moll, a young prostitute, is arrested when she refuses a proposition from a corrupt policeman. She is soon joined at night court by members of the Liberty Committee, an anti-union group mistakenly charged with pro-union activities. While the committee members call out to be freed by their patron, industrialist Mr. Mister, a derelict named Harry Druggist befriends Moll and explains that he lost his business because of Mr. Mister.

Harry relates how Mr. Mister came to dominate Steeltown: Years earlier, during World War I, Mr. Mister's wife pays the town priest, Reverend Salvation, to preach sermons supporting her husband's interests. Editor Daily, the head of the local newspaper, begins running articles attacking the steelworkers union and its leader, Larry Foreman, while also hiring the inept Junior Mister as a foreign correspondent. Gus Polack, a newly elected member of the union, is murdered in a car bombing that also kills his wife and unborn child, as well as Harry's son Stevie. Harry is pressured to keep quiet. He subsequently loses his business permit and falls into alcoholic despair.

Eventually, all of Steeltown's prominent citizens join the Liberty Committee, including Salvation, Daily, the painter Dauber, and the violinist Yasha. With their support, Mr. Mister's rule over the town seems unshakeable.

Later that night, Larry is arrested and beaten for distributing leaflets. He urges the others to join him and rise against Mr. Mister, saying that, in time, "the cradle will rock".

A flashback shows Mr. Mister persuading President Prexy of Steeltown University to threaten students with expulsion if they do not join the army. Dr. Specialist, the chairman of the Liberty Committee, is told to cover up the death of a steelworker by writing it off as a drunken accident. He does so even when the worker's sister, Ella Hammer, confronts him with the truth.

Later that evening, Mr. Mister arrives and bails out the committee members. He offers to pay off Foreman, but he refuses. As the committee jeers him, he defiantly declares that Mr. Mister's power over Steeltown will soon come to an end as the curtain falls.

Musical numbers

The Cradle Will Rock is presented in ten scenes. In the original Federal Theatre Project production, it was performed without an intermission. At the June 16 performance at the Venice Theatre, a 15-minute intermission was an impromptu addition following scene six,[7]: 272 to spare Marc Blitzstein from exhaustion.[5]: 229

No musical numbers were listed in the program.[12][13] Six songs were printed in the libretto published by Random House; those and others were titled and copyrighted by Blitzstein as individual works in 1938.[14]

| Scene | Title + Performer | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Streetcorner | "I'm Checkin' Home Now" – Moll (mezzo) | [15][16] |

| 2: Nightcourt | ||

| 3: Mission | "Mission Scene" – Mrs. Mister (mezzo), Reverend Salvation (baritone) | [15][16] |

| 4: Lawn of Mr. Mister's Home | "Croon Spoon" – Junior Mister (tenor), Sister Mister (mezzo) "The Freedom of the Press" – Editor Daily (tenor), Mr. Mister (baritone) "Honolulu" – Editor Daily, Junior Mister, Mr. Mister, Sister Mister |

[17]: 53–56 [16] [15][16] [17]: 65–70 |

| 5: Drugstore | "Drugstore Scene" – Harry Druggist (baritone), Steve "Gus and Sadie Love Song" – Gus Polock (baritone), Sadie Polock (soprano) |

[15] [17]: 83–84 [16] |

| 6: Hotellobby | "The Rich" – Yasha (baritone), Dauber (baritone) "Ask Us Again" – Yasha, Dauber, Mrs. Mister "Art for Art's Sake" – Yasha, Dauber |

[15][16] [15] [15] |

| 7: Nightcourt | "Nickel Under the Foot" – Moll "Leaflets" – Larry Foreman (baritone) "The Cradle Will Rock" – Larry Foreman |

[17]: 99–102 [15][16] [17]: 109–112 |

| 8: Facultyroom | ||

| 9: Dr. Specialist's Office | "Doctor and Ella" – Ella Hammer (alto), Doctor Specialist "Joe Worker" – Ella Hammer |

[15][16] [17]: 133–136 |

| 10: Nightcourt | "Finale" – Ensemble | [15] |

Original production

Federal Theatre Project

At any rate, on the chance that we might never really open, Welles and Houseman invited to our final dress rehearsal the most elite New York audience imaginable. That rehearsal was the first and the last time the work has ever been fully performed exactly as I wrote it. It seemed a success.

— Marc Blitzstein in 1956, recalling the full-orchestra dress rehearsal at Maxine Elliott's Theatre on June 14, 1937[6]

Rehearsals for The Cradle Will Rock began March 8, 1937.[5]: 223 The 32-member orchestra,[4]: 173 conducted by music director Lehman Engel, started rehearsals in mid-April.[10]: 138 Members of the large company would have two months or more of rehearsal time and employment as the show was prepared—a luxury that the Federal Theatre Project, as a New Deal work-relief program, was designed to afford.[4]: 174 Everyone, including Blitzstein, was paid $23.86 a week.[10]: 138

Having arranged for Howard da Silva to play labor organizer Larry Foreman, Welles cast Will Geer as capitalist boss Mr. Mister. For the role of Moll, the young woman who prostitutes herself to avoid starving, he found Olive Stanton, an actress who had appeared in the Federal Theatre Project production Class of '29 (1936). She was a daughter of Sanford E. Stanton, a political reporter and columnist for the New York Journal-American.[8]: 386 [18]

An ingenue in early Universal Pictures films, Peggy Coudray (Mrs. Mister) had earned praise for her comedy skills in soubrette roles in stage musicals and operettas.[10]: 137 She had performed with Edward Arnold in vaudeville and led her own stock companies.[13]: 14 The comic actor Hiram Sherman (Junior Mister) was a childhood friend of Welles and a veteran of his farce Horse Eats Hat. Other cast were selected for the clarity and strength of their voices, supplemented by an interracial chorus of 44 singers.[10]: 137

The Cradle Will Rock was choreographed by Clarence Yates,[10]: 138 an African-American dancer and choreographer who studied ballet with Michel Fokine. He was director of dance for the Federal Theatre Project's Negro Theatre Unit in New York City.[19] He and Asadata Dafora choreographed Welles's Voodoo Macbeth,[20] and Yates was in the cast of his Doctor Faustus.[21]

-

Clarence Yates (foreground) rehearsing cast members at Maxine Elliott's Theatre

-

Yates rehearsing the cast

-

Yates rehearsing the cast

-

From left: George Fairchild, Olive Stanton, Will Geer, Hiram Sherman, Peggy Coudray, Yates

-

Yates rehearsing the cast

-

Stanton rehearsing

-

Yates rehearsing Stanton

-

Stanton, Yates, Coudray

-

Stanton, Yates, Coudray

"It is not very fashionable these days to refer admiringly to the Federal Theatre Project, and yet it was responsible for a great number of today's writers, stars, directors and stage designers," Blitzstein said in a 1956 interview. "We had unlimited time to prepare the production and we had really quite extraordinary talents in every department at our disposal. Rehearsals moved toward a state of perfection rarely attained in our present‐day theater."[6]

The production's costume and scenic designer was Edwin J. Schruers. "Of course it was really Orson," wrote Blitzstein.[5]: 226 Welles talked Blitzstein into a flashy stage design "full of metal and glass and the horror of Steeltown":[3]: 132

I told Marc he shouldn't do an opera for the ladies' garment workers and the communist union. Instead, he should do it for Vanity Fair, Vogue and Harper's audiences, and it should have no atmosphere of being a little labor opera. It should be a big Broadway show.[22]: 159

Houseman described "an extravagant scenic scheme that called for a triple row of three-dimensional velour portals between which narrow glass-bottomed fluorescent platforms, loaded with scenery and props, slid smoothly past each other as the scene shifted back and forth".[7]: 248 The scene plot indicates four of these illuminated trucks, as well as screens, two travelers, a double-quarter revolve and an inventive aperture curtain.[9]: 293 Accustomed to an open stage and the accompaniment of only Blitzstein's piano, the well-rehearsed cast was disconcerted by the sliding scenery and large orchestra.[8]: 386–387

To plan the blocking and performances, Welles had to know the music. "He would start at ten in the morning and not leave the theatre," said conductor Lehman Engel. "He might dismiss his cast at four the next morning but when we would return at noon, we would find Orson sleeping in a theatre seat."[8]: 387

Houseman and Welles would not commit to a schedule for some weeks, while Welles's Doctor Faustus continued to sell out at Maxine Elliott's Theatre.[8]: 387 Faustus finally suspended performances on May 29.[3]: 132 Public previews of The Cradle Will Rock were announced to begin June 16, with an official opening at the end of June.[4]: 174 After a few weeks' run, the musical was to play in repertory with Faustus[8]: 387 and another production to be announced.

"On June 10," Flanagan wrote, "after weeks of debate in Washington we received the definite order to cut the New York project by 30 percent, involving the dismissal of 1,701 workers."[11]: 202 Flanagan received another memorandum June 12, stating that "no openings of new productions shall take place until after the beginning of the coming fiscal year" due to an expected cut in federal appropriations. Because The Cradle Will Rock was the only new production opening in the last two weeks of June,[23] Flanagan concluded that "this was obviously censorship under a different guise."[11]: 202–203

Nineteen benefit performances had been scheduled for The Cradle Will Rock through July 24, with 18,000 tickets sold. The first public preview on June 16 was a sold-out benefit for the Downtown Music School.[5]: 227 "As producers, Orson and I were not noted for our punctuality," Houseman wrote, adding that their Macbeth was postponed five times, Horse Eats Hat twice, and Faustus three times. "Normally, we would almost certainly have postponed the opening of The Cradle. But now, suddenly, we became demons of dependability, scrupulous to honor our public and artistic commitment. Hallie asked me how I felt about the delay. I told her we refused to accept it."[7]: 255

The Federal Theatre Project 891 version of The Cradle Will Rock was publicly performed only once, at a full-orchestra dress rehearsal on June 14. The hastily invited audience of several hundred people included producer Arthur Hopkins, playwrights Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman, and writer and editor V. J. Jerome.[7]: 256 [24]: 41 Syndicated columnist Jay Franklin reported: "Those who saw the dress rehearsal say that it is a gay, fast-moving, exciting show—one which subjects the social scene to radical criticism and still retains a sense of humor and of proportion."[5]: 225

On June 15, the WPA padlocked Maxine Elliott's Theatre. Uniformed guards prevented anyone from removing props or costumes, which were U.S. government property.[7]: 256 [25]

"The hammer fell in the form of considerable governmental budget cuts just as Cradle was to open," Welles said, "at the height of the CIO's efforts to organize steel. Another reason for closing us was that, unlike most WPA plays, we were going to be on Broadway, which opponents feared would attract considerable attention."[22]: 160

Private sponsorship

So Jack Houseman and Orson Welles took the play down the street and opened it under private auspices as the first production of the Mercury Theatre. Probably it was worth a case of censorship to launch a group of our most brilliant directors and actors with a play for which the cast and rehearsal time had been provided, as well as an audience and a springboard for publicity.

— Hallie Flanagan, national director of the Federal Theatre Project[11]: 203

Welles, Houseman and Blitzstein, seeking a way to privately produce the show, rented the much larger Venice Theatre and a piano just in time for the scheduled preview on June 16, 1937.[26] The 600 audience members, who had gathered outside the Maxine Elliot Theatre for the preview, travelled 21 blocks north to the Venice Theatre; many were on foot.[1][25] The sold-out house grew even larger when the show's creators invited people off the street to attend for free. The musicians' union refused to play for the show unless Houseman could provide their full salaries, and Actors' Equity Association stated that its members could not perform onstage at the new theatre without approval of the original producer (the federal government).[25] The show's creators thus planned for Blitzstein to perform the entire musical at the piano.[25] Just after beginning the first number, Blitzstein was joined by Olive Stanton, the actress playing Moll, from the audience.[25] During the rest of the performance, various actors joined in with Blitzstein and performed the entire musical from the house.[27] According to The New York Times's description of the original production, "Persons who heard the opera's score and extracts last night carried no clear impression except that its theme was that steel workers should join a union." Poet Archibald MacLeish, who was in the audience, "praised the 'vitality' of the Federal Theatre Project."[1]

Houseman determined that there were no legal restrictions on performing the musical with a new financial backer, and beginning on June 18, Helen Deutsch, press agent for the Theatre Guild, agreed to serve as the financial backer for The Cradle Will Rock; the actors received a two-week leave of absence from the WPA, and, in an agreement with Actors' Equity, Deutsch paid the 19 cast members $1500 for the two weeks' performances.[26] Two days later, Houseman announced that, should the production prove successful, the two-week run would be continued indefinitely.[28] Houseman also announced that the musical would continue to be performed with Blitzstein playing piano onstage and the cast members singing from the audience. He asserted that this made the audience feel like part of the show, stating, "There has always been the question of how to produce a labor show so the audience feels like it is a part of the performance. This technique seems to solve that problem and is exactly the right one for this particular piece".[28] The success of the performance led Welles and Houseman to form the Mercury Theatre.[29][citation needed]

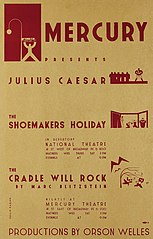

Mercury Theatre

The Cradle Will Rock was presented by the Mercury Theatre as part of its inaugural season. On December 5, 1937, it opened in a reduced oratorio version on Sunday evenings at the Mercury Theatre, using the set for Caesar and two rows of chairs. The cast included Will Geer, Howard da Silva, Hiram Sherman, a chorus of 12, and Marc Blitzstein at the piano.[30]: 340

Presented by the Mercury Theatre and Sam H. Grisman, the oratorio version of The Cradle Will Rock moved to the Windsor Theatre January 4, 1938. In mid-February it returned to the Mercury Theatre and completed its 13-week run April 2, 1938.[30]: 340 [7]: 341–342

-

Marc Blitzstein, Howard da Silva and Olive Stanton in the Mercury Theatre presentation of The Cradle Will Rock

-

Entire cast of the Mercury Theatre presentation of The Cradle Will Rock, with all the scenic effects used

-

Mercury Theatre poster (1938)

-

Blitzstein (with Stanton leaning on the piano, January 1938)

-

Da Silva and Stanton (January 1938)

Later productions

Broadway and Off-Broadway

The musical was revived on Broadway on December 26, 1947,[31] at the Mansfield Theatre, then moving to the Broadway Theatre, with a cast that included Alfred Drake (Larry Foreman), Vivian Vance (Mrs. Mister), Jack Albertson (Yasha), and original cast member Will Geer (Mr. Mister). The production was directed by Howard da Silva[32] and played 34 performances.[33]

The show was revived Off-Broadway in 1964 in a production starring Jerry Orbach (Larry Foreman), Nancy Andrews (Mrs. Mister), and Lauri Peters (Moll), directed by Howard da Silva. Leonard Bernstein acted as music supervisor to music director Gershon Kingsley. The production ran at Theatre Four for 82 performances. This production won the Obie Award as Best Musical Production and Dean Dittman (who played Editor Daily) won the Obie for Distinguished Performance.[34][35][36]

The Acting Company presented an Off-Broadway production at the American Place Theater from May 9, 1983 to May 29, 1983, directed by John Houseman and featuring a spoken introduction by Houseman, and starring Patti LuPone.[25][37] This production was done "on a dark stage, decorated only with chairs and Dennis Parichy's poetic lighting. At dead center is the upright piano, whose expert player, Michael Barrett, delivers the Brechtian scene-setting announcements as Blitzstein once did."[38] The production was recorded for television and aired on PBS in 1986.[39]

Other productions

Blitzstein's rarely heard orchestrations were used in a February 21, 1960, broadcast by the New York City Opera featuring Tammy Grimes and David Atkinson.[40]

The show was revived in 1985 at The Old Vic (near Waterloo Station) featuring alumni members of The Acting Company.[41] In this production Patti LuPone reprised her role as Moll and was honored with an Olivier Award for Best Actress in a Musical.[42]

Splinter Group Theatre's Chicago production in 1994 was named one of the Ten Best plays of the year by the Chicago Tribune.[43] Directed by Matt O'Brien, with musical direction by Jim Collins, the production style recreated the bare bones approach necessitated by the 1937 production's opening night, and later transferred from Splinter Group's space in Wicker Park to the larger Theatre Building in Chicago, running a total of three months in the two locations.

Mehmet Ergen directed a production in London for the Arcola Theatre's 10th Anniversary in 2010 starring Alicia Davies, Stuart Matthew Price, Morgan Deare, Chris Jenkins and Josie Benson. It was the last show at the Arcola Street location, before the company moved to its new space, opposite the Dalston Junction station.[44]

The Oberlin Summer Theater Festival staged a summer stock production in 2012.[45] Directed by Joey Rizzolo, one of the New York Neo-Futurists (who are known for their Brechtian approach to theater), the production opened to critical acclaim.[46]

Response

Cultural references

The Cradle Will Rock

In 1984, Orson Welles wrote the screenplay for a film he planned to direct—The Cradle Will Rock, an autobiographical drama about the 1937 staging of Blitzstein's play.[22]: 157–159 Rupert Everett was cast to portray the 21-year-old Welles[47]: 117 in the black-and-white feature film. Welles's first wife Virginia Nicolson is a sympathetically written key character in the unproduced screenplay, one of Welles's last important pieces of writing.[8]: 384 She read and approved the screenplay during preproduction. John Houseman read it after Welles's death and remarked on the screenplay's accuracy and fairness.[48]

Although the budget was reduced to $3 million,[48] Welles was unable to secure funding and the project was not realized.[22]: 215–220

"A couple of studio reports that I've read on the Cradle script seem characteristic," wrote film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum. "Both readers complain that the script assumes an interest in Welles's early life that they didn't happen to share."[48] The unproduced screenplay was published in 1994.[47]

Cradle Will Rock

In 1999 writer/director Tim Robbins wrote a semi-fictional film recounting the original production of The Cradle Will Rock. The film, entitled Cradle Will Rock (without "The") blended the true history of Blitzstein's show with the creation (and subsequent destruction) of the original Diego Rivera mural Man at the Crossroads in the lobby of Rockefeller Center (the Rivera mural was actually destroyed in 1934). Several of the original actors from the 1937 production were included as characters in the film, notably Olive Stanton, John Adair, and Will Geer, while others were replaced by fictional characters. Leading man Howard da Silva was replaced by the fictional "Aldo Silvano" (John Turturro). Although Will Geer played Mr. Mister in the 1937 production, for the movie he was recast in the smaller role of the Druggist. The name of the actor who played Doctor Specialist in the original production is given to the fictional character "Frank Marvel" (Barnard Hughes), who plays Mr. Mister.

The film's climax recreates scenes from the original, legendary performance of the show, performed by veteran Broadway performers Victoria Clark, Gregg Edelman, Audra McDonald, Daniel Jenkins, Erin Hill, and Chris McKinney.

Robbins wrote a book, Cradle Will Rock: The Movie and the Moment, as a companion to the movie; it discusses the original show, his adaptation, and the filming of the motion picture.[49]

Recordings

A slightly abridged version of Welles's 1937 Mercury Theatre production with narration by Blitzstein was recorded in April 1938 and released on the Musicraft label (number 18). It was the first original cast recording ever made. A digital version of the Musicraft 78s is available through the Internet Archive.[50]

In December 1964 the recording was re-released in a limited-edition LP on the American Legacy Records label (T1001).[30]: 342 [51]: 251

Discography

key to casts: Moll/Ella Hammer/Editor Daily/Larry Foreman/Mr. Mister

- 1938 – label: Musicraft – conductor: Blitzstein – cast: Stanton/Collins/Weston/da Silva/MacBane

- 1964 – label: MGM – conductor: Kingsley – cast: Peters-L/Grant/Dittmann/Orbach/Clarke

- 1985 – label: TER – conductor: Barrett – cast: LuPone/Woods-MD/Matthews-A/Mell/Schramm

- 1994 – label: Lockett-Palmer – conductor: Bates – cast: Dawn?/Green-MP?/Lund?/Baratta?/van Norden?

- 1999 – label: RCA Victor – conductor: Campbell – cast: Harvey/McDonald/unknown/unknown/unknown (soundtrack of Robbins movie; music is abridged)

References

- ^ a b c "Steel Strike Opera Is Put Off by WPA". The New York Times. June 17, 1937. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ "Broadway World - #1 for Broadway Shows, Theatre, Entertainment, Tickets & More!".

- ^ a b c d Leaming, Barbara (1985). Orson Welles: A Biography. Viking. ISBN 978-0670528950.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Pollack, Howard (2012). Marc Blitzstein: His Life, His Work, His World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979159-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lehrman, Leonard J. (2005). Marc Blitzstein: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 9780313300271.

- ^ a b c Blitzstein, Marc (April 12, 1964). "As He Remembered It". The New York Times. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Houseman, John (1972). Run-Through: A Memoir. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-21034-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j McGilligan, Patrick (2015). Young Orson. New York: Harper. ISBN 978-0062112484.

- ^ a b Callow, Simon (1996). Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu. Viking. ISBN 978-0099462514.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gordon, Eric A. (1989). Mark the Music: The Life and Work of Marc Blitzstein. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-02607-2.

- ^ a b c d e Flanagan, Hallie (1965). Arena: The History of the Federal Theatre. New York: Benjamin Blom, reprint edition [1940]. OCLC 855945294.

- ^ "The Cradle Will Rock (Federal Theatre Project playbill)". Library of Congress. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Cradle Will Rock (Windsor Theatre)". Playbill. January 3, 1938. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Catalog of Copyright Entries: Musical Compositions, Part 3. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1939. p. 1718.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j The Cradle Will Rock (Media notes). New York City: American Legacy Records. December 1964. p. 1. T1001. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lehrman, Leonard J. (2005). Marc Blitzstein: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. p. 221. ISBN 9780313300271.

- ^ a b c d e f Blitzstein, Marc (1938). The Cradle Will Rock. New York: Random House. OCLC 1597731.

- ^ Stanton, Ted (December 26, 1999). "Cradle Will Rock: The True 'Toddy'". The New York Times. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ Oja, Carol J. (2014). Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War. Oxford University Press. pp. 161–162. ISBN 978-0-19-986209-2.

- ^ Perpener, John O. (2001). African-American Concert Dance: The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. p. 117. ISBN 9780252026751.

- ^ "The Tragical History of Dr. Faustus". Library of Congress. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Tarbox, Todd (2013). Orson Welles and Roger Hill: A Friendship in Three Acts. Albany, Georgia: BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-59393-260-2.

- ^ O'Connor, John; Brown, Lorraine (1978). Free, Adult, Uncensored: The Living History of the Federal Theatre Project. Washington, D.C.: New Republic Books. p. 27. ISBN 0-915220-37-7.

- ^ Wood, Bret (1990). Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313265389.

- ^ a b c d e f Leiter, Robert (May 1, 1983). "A New Look at the 'Cradle' That Rocked Broadway". The New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ a b "WPA Opera Put On as Private Show; 'The Cradle Will Rock' Is Given Commercially at the Venice Theatre Here". The New York Times. June 19, 1937. Retrieved 2017-12-27.

- ^ Block, Geoffrey.'The Cradle Will Rock' Enchanted Evenings, Oxford University Press US, 2004, ISBN 0-19-516730-9, p. 117

- ^ a b "'Cradle Will Rock' Will Continue Run". The New York Times. June 20, 1937. Retrieved 2017-12-27.

- ^ The details of the first production were recounted by John Houseman in an introductory speech to a 1983 production by The Acting Company, recorded by Jay Records, and are also included in Houseman's memoirs.

- ^ a b c Welles, Orson, and Peter Bogdanovich, edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum, This is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins Publishers 1992 ISBN 0-06-016616-9

- ^ Green, Stanley and Green, Kay."'The Cradle Will Rock' listing" Broadway Musicals, Show by Show (Ed.5), Hal Leonard Corporation, 1996, ISBN 0-7935-7750-0, p. 101

- ^ Atkinson, Brooks."Blitzstein's 'Cradle Will Rock,' Vivid Proletarian Drama, Revived at Mansfield" The New York Times (abstract), December 27, 1947, p. 11

- ^ The Cradle Will Rock, 1947, Internet Broadway Database, accessed March 8, 2011

- ^ Funke, Lewis.Cradle Will Rock' Is at Theater Four" The New York Times (abstract), November 9, 1964, p.40

- ^ "'The Cradle Will Rock' Listing, 1964" Internet Off-Broadway Database, accessed March 8, 2011

- ^ "Obie Awards, 1964-1965" InfoPlease.com, accessed March 9, 2011

- ^ "'The Cradle Will Rock' Listing" Internet Off-Broadway Database listing, accessed March 8, 2011

- ^ Rich, Frank. "Theater: 'Labor Opera' By Blitzstein Is Revived", The New York Times, May 10, 1983, Section C, p. 11

- ^ Holden, Stephen (1986-01-29). "'THE CRADLE WILL ROCK,' BLITZSTEIN'S LABOR OPERA (Published 1986)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-12-29.

- ^ Taubman, Howard."Radical '30's Recalled In 'Cradle Will Rock'", The New York Times (abstract), February 21, 1960

- ^ "LuPone Reprises Role in Cradle Will Rock", playbill.com, accessed October 20, 2015

- ^ "Olivier Winners 1985" Archived 2012-04-19 at the Wayback Machine, olivierawards.com, accessed March 8, 2011

- ^ Critic, Sid Smith, Tribune Arts. "'CRADLE WILL ROCK' KEEPS MUCH OF THE BITE OF 1937 ORIGINAL". chicagotribune.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Arcola Theatre Listing, The Cradle Will Rock'" Arcola Theatre.com, accessed March 8, 2011

- ^ "Oberlin Summer Theater Festival Listing, The Cradle Will Rock'" oberlin.edu, accessed August 6, 2012

- ^ "Scene Magazine review by Christine Howey", clevescene.com, accessed August 6, 2012

- ^ a b Welles, Orson (1994). Pepper, James (ed.). The Cradle Will Rock: An Original Screenplay. Santa Barbara, California: Santa Teresa Press. ISBN 978-0-944166-06-2.

- ^ a b c Rosenbaum, Jonathan (June 17, 1994). "Afterword to The Cradle Will Rock, a screenplay by Orson Welles". jonathanrosenbaum.net. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Robbins, Tim (1999). Cradle Will Rock: The Movie and the Moment. Newmarket Press. ISBN 978-1-55704-399-3.

- ^ "The Cradle Will Rock: original cast recording". 10 September 1989 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Lehrman, Leonard, Marc Blitzstein: A Bio-bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2005. ISBN 9780313300271

External links

- The Cradle Will Rock information on marc-blitzstein.org. Includes scoring, cast, publication info, synopsis, press clippings and commentary.

- The Cradle Will Rock: a detailed analysis by Scott Miller, newlinetheatre.com, with background to the 1937 musical and discussion of the 1999 movie

- The Cradle Will Rock at the Internet Broadway Database