Dulles International Airport

Washington Dulles International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dulles International Airport's main terminal at dusk, 2011 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner/Operator | Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Washington metropolitan area, Northern Virginia, Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Dulles, Virginia, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | November 17, 1962 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 313 ft / 95 m | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 38°56′40″N 077°27′21″W / 38.94444°N 77.45583°W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | flydulles.com | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

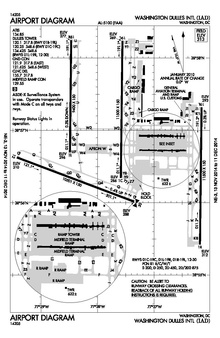

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FAA airport diagram | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2022) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Washington Dulles International Airport (IATA: IAD, ICAO: KIAD, FAA LID: IAD), typically referred to as Dulles International Airport, Dulles Airport, Washington Dulles, or Dulles (/ˈdʌlɪs/ DUL-iss), is an international airport in the Mid-Atlantic United States in Loudoun County and Fairfax County, Virginia, 26 miles (42 km) west of Downtown Washington, D.C.[4] and 29 miles (47 km) from Ronald Reagan National Airport in Arlington County, Virginia.

The airport, which opened in 1962, is named after John Foster Dulles, an influential U.S. Secretary of State during the Cold War.[5][6] The airport's main terminal is a well-known landmark designed by Eero Saarinen, who also designed the TWA Flight Center at John F. Kennedy International Airport. Operated by the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority, Washington Dulles Airport occupies 13,000 acres (20.3 sq mi; 52.6 km2),[2][7] straddling the Loudoun–Fairfax line.[8] Most of the airport is in the unincorporated community of Dulles in Loudoun County, with a small portion in the unincorporated community of Chantilly in Fairfax County.

Along with Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA) and Baltimore/Washington International Airport (BWI), Dulles is one of three major airports serving the Washington-Baltimore metropolitan area. As of 2021, it is the second-busiest airport in the Washington-Baltimore metropolitan area and 28th-busiest airport in the U.S.[9] Dulles has the most international passenger traffic of any airport in the Mid-Atlantic outside the New York metropolitan area, including approximately 90% of the international passenger traffic in the Baltimore–Washington region.[10] It had more than 20 million passenger enplanements every year from 2004 to 2019, with 24 million enplanements in 2019.[11][12] An average of 60,000 passengers pass through Dulles daily to and from more than 139 destinations around the world.[11][13][14]

Increased domestic travel from Reagan National Airport has eroded some of Dulles' domestic routes.[9] Dulles overtook Reagan in total enplanements in 2019.[15] However, in 2018, Dulles surpassed Reagan in yearly passenger boardings after having fewer passengers since 2015.[16] Furthermore, it still ranks behind BWI in total annual passenger boardings.[17]

Dulles is a fortress hub for United Airlines and is frequently used by airlines that United has codeshare agreements with, mostly composed of Star Alliance members like Turkish Airlines and Lufthansa.

History

Origins

Before World War II, Hoover Field was the main commercial airport serving Washington, on the site now occupied by the Pentagon and its parking lots. It was replaced by Washington National Airport in 1941, a short distance southeast. After the war, in 1948, the Civil Aeronautics Administration began to consider sites for a second major airport to serve the nation's capital.[18] Congress passed the Washington Airport Act in 1950 to provide funding for a new airport in the region.[19] The initial CAA proposal in 1951 called for the airport to be built in Fairfax County near what is now Burke Lake Park, but protests from residents, as well as the rapid expansion of Washington's suburbs during the time, led to reconsideration of this plan.[20] One competing plan called for the airport to be built in the Pender area of Fairfax County, while another called for the conversion of Andrews Air Force Base in Prince George's County, Maryland, into a commercial airport.[18]

The current site was selected by President Eisenhower in 1958;[20] the Dulles name was chosen by Eisenhower's aviation advisor Pete Quesada, who later served as the first head of the Federal Aviation Administration. As a result of the site selection, the unincorporated, largely African-American community of Willard, which once stood in the airport's current footprint, was demolished, and 87 property owners had their holdings condemned.[18]

Dulles was also built over a lesser-known airport named Blue Ridge Airport, chartered in 1938 by the U.S. The airport was Loudoun County's first official airport, consisting of two grass intersecting runways in the shape of an "X". The location of the former Blue Ridge Airport sits where the Dulles Air Freight complex and Washington Dulles Airport Marriott now sit today.[21][better source needed]

Design and construction

The civil engineering firm Ammann and Whitney was named lead contractor. The airport was dedicated by President John F. Kennedy and Eisenhower on November 17, 1962.[5][6][22] As originally opened, the airport had three long runways (current day runways 1C/19C, 1R/19L, and 12/30) and one shorter one (where current taxiway Q is located). Its original name, Dulles International Airport, was changed in 1984 to Washington Dulles International Airport.[23]

The main terminal was designed in 1958 by famed Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen, and it is highly regarded for its graceful beauty, suggestive of flight. In the 1990s, the main terminal at Dulles was reconfigured to allow more space between the front of the building and the ticket counters. Additions at both ends of the main terminal more than doubled the structure's length. The original terminal at Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport in Taoyuan, Taiwan, was modeled after the Saarinen terminal at Dulles.[citation needed]

The design included a landscaped man-made lake to collect rainwater, a low-rise hotel, and a row of office buildings along the north side of the main parking lot. The design also included a two-level road in front of the terminal to separate arrival and departure traffic and a federally owned limited access highway connecting the terminal to the Capital Beltway (I-495) about 17 miles (27 km) to the east. (Eventually, the highway system grew to include a parallel toll road to handle commuter traffic and an extension to connect to I-66). The access road had a wide median strip to allow the construction of a passenger rail line, which opened as an extension of the Washington Metro's Silver Line on November 15, 2022.[24]

Notable operations and milestones

- The first scheduled flight at Dulles was an Eastern Air Lines Super Electra from Newark International Airport in New Jersey on November 19, 1962.[8]

- Dulles was initially considered a white elephant, being far out of town with few flights;[25] in 1965 Dulles averaged 89 airline operations a day while National Airport (now Reagan) averaged 600 despite not allowing jets.[26] (Dulles got its first transatlantic nonstop in June 1964.) Airport operations grew along with Virginia suburbs and the Dulles Technology Corridor; perimeter and slot restrictions at National forced long-distance flights to use Dulles. In 1969, Dulles had 2.01 million passengers while National had 9.9 million.[27]

- The era of widebody jets began on January 15, 1970, when First Lady Pat Nixon christened a Pan Am Boeing 747-100 at Dulles in the presence of Pan Am chairman Najeeb Halaby.[28] Rather than a traditional champagne bottle, red, white, and blue water was sprayed on the aircraft.[29] Pan Am's first Boeing 747 flight was from New York JFK to London Heathrow Airport.

- On May 24, 1976, supersonic flights between the U.S. and Europe began with the arrival of a British Airways Concorde from London Heathrow and an Air France Concorde from Paris Charles De Gaulle.[30][31][32] The two were lined nose-to-nose at Dulles for photos.

- On June 12, 1983, the Space Shuttle Enterprise arrived at Dulles atop a modified Boeing 747 after touring Europe and before returning to Edwards Air Force Base. Two years later Enterprise returned and was placed in a storage hangar near Runway 12/30 to await construction of a planned expansion to the National Air and Space Museum. Enterprise left Dulles on April 27, 2012, for its new home at the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York City.[33]

- In 1990 a United States Senate joint resolution to change Dulles's name to Washington Eisenhower was proposed by Senator Bob Dole, but it didn't pass.[34]

- When the SR-71 was retired by the military in 1990, one was flown from its birthplace at United States Air Force Plant 42 in Palmdale, California, to Dulles, setting a coast-to-coast speed record at an average 2,124 mph (3,418 km/h). The trip took 64 minutes. The aircraft was placed in a storage building, and is now displayed at the Smithsonian's adjacent Udvar-Hazy Air and Space Museum.[35]

- The first flight of the Boeing 777-200 in commercial service, a United Airlines flight from London Heathrow, landed at Dulles in 1995.[36]

- The 2004 launch of low-cost carrier Independence Air propelled IAD from being the 24th-busiest airport in the United States to fourth, and one of the top 30 busiest in the world. Independence Air ceased operations in January 2006, and its space in Concourse A was taken five months later by United Express.[37]

- Southwest Airlines began service at Dulles in fall 2006.

- Significant growth required the airport to halt the operations of its iconic original control tower in 2007 for a much taller control tower located away from the main terminal. The original tower still exists, though it is no longer used to control the airport's traffic.

- In 2007, 24.7 million passengers passed through the airport.[38]

- On November 20, 2008, a third parallel north–south runway opened on the west side of the airfield, designated 1L/19R. The original 1L/19R was re-designated 1C/19C. It was the first new runway to be built at Dulles since the airport's construction.

- On June 6, 2011, the airport received its first Airbus A380 flights when Air France introduced the A380 on its nonstop from Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport during peak season.[8]

- On April 17, 2012, the Space Shuttle Discovery was ferried to Dulles mounted to a NASA 747-100 as part of its decommissioning and installation in the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.[39]

- On June 1, 2012, the first passenger flight of the Boeing 747-8 Intercontinental landed as a Lufthansa service from Frankfurt Airport.[40]

- On August 15, 2012, the first Ethiopian Airlines Boeing 787 Dreamliner arrived at Washington Dulles.[41] It was Ethiopian Airlines' first 787 & the first 787 received by an African carrier.

- On October 2, 2014, British Airways began using the Airbus A380 on flights from London Heathrow Airport to Dulles. However, it temporarily ended A380 flights, reverting to a 747-400 twice daily during peak season, but in October 2019 British Airways resumed back to once-daily A380 operations during non-peak season, before ending operations to Dulles on the A380, once again, in early 2020.

- On February 1, 2016, Emirates upgraded its direct flights from Dubai International (previously a Boeing 777) to an Airbus A380.[42]

- As of 2019[update], Washington Dulles is only one of fourteen airports in the United States that sees daily operations from, and/or has at least one gate and one runway that can accommodate an Airbus A380; the others being Atlanta, Boston, Chicago-O'Hare, Dallas/Fort Worth, Denver, Honolulu, Houston-Intercontinental, Las Vegas, Los Angeles-LAX, Miami, New York–JFK, Orlando and San Francisco.[43]

- On May 16, 2018, Volaris Costa Rica launched flights to Dulles, becoming the first international low-cost carrier to serve the airport.[44]

- On September 15, 2018, Cathay Pacific launched its longest nonstop route connecting Dulles to Hong Kong utilizing an Airbus A350-1000. The service has since alternated between the −900 and −1000 depending on season. However, this service has been temporarily suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[45][46]

- In 2019, four new major international routes were added. Alitalia began non-stop service utilizing an Airbus A330 to Rome-Fiumicino, operating five times weekly during the peak summer season, reducing to three times weekly during the winter season.[47] EgyptAir operates a Boeing 787–9 with nonstop service to Cairo three times a week year-round.[48] TAP Air Portugal flies five times weekly with nonstop service to Lisbon onboard the Airbus A321LR, A330-900 and sometimes the A330-200. As of May 2019, United began non-stop service to Tel-Aviv, initially utilizing a Boeing 777-200ER on a thrice-weekly schedule, currently operated with a Boeing 787-8.[49]

- In 2020, LOT Polish, Iberia and Swiss were all scheduled to begin service to Dulles, but these were postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. LOT Polish were scheduled to provide Boeing 787 service from Warsaw, Iberia to provide Airbus A330-300 service from Madrid, and Swiss to provide Airbus A330-300 service from Zürich. So far only the Iberia route has been implemented.

- In 2021, regional airline Southern Airways Express moved their East Coast hub from BWI to Dulles.[50] Southern Airways will operate flights between Dulles and small airports in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, some of them on Essential Air Service contracts.

- On November 15, 2022, the airport's Washington Metro station opened as part of the Phase 2 extension of the Silver Line, from Wiehle–Reston East station to Ashburn.

Planned development

By the 1980s the original design, featuring mobile lounges to meet each plane, was no longer well-suited to Dulles' role as a hub airport. Instead, midfield concourses were constructed to allow passengers to walk between connecting flights without visiting the main terminal. Mobile lounges were still used for international flights and to transport passengers between the midfield concourses and the main terminal; Concourse C/D was the first to be built, followed by Concourse A/B. A tunnel (consisting of a passenger walkway and moving sidewalks) which links the main terminal and Concourse B was opened in 2004.[51] The Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA) began a renovation program for the airport including a new security mezzanine with more room for lines.[52]

A new train system, dubbed AeroTrain and developed by Mitsubishi, began in 2010 to transport passengers between the concourses and the main terminal.[53] The system, which uses rubber tires and travels along a fixed underground guideway,[53] is similar to the people mover systems at Singapore Changi Airport,[53] Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport, and Denver International Airport. The train is intended to replace the mobile lounges, which many passengers found crowded and inconvenient. The initial phase includes the main terminal station, a permanent Concourse A station, a permanent Concourse B station, a permanent midfield concourse station (with access to the current temporary C concourse via a tunnel with moving walkways), and a maintenance facility.[53] Mobile lounges continue to service Concourse D from both the main terminal and Concourse A. Even after AeroTrain is built out and the replacement Concourses C and D are built, the mobile lounges and plane mates will still continue to be used, to transport international arriving passengers to the International Arrivals Building, as well as transport passengers to aircraft parked on hardstands without direct access to jet bridges. Dulles has stated that the wait time for a train does not exceed four minutes, compared to the average 15-minute wait and travel time for mobile lounges.[citation needed]

Under the development plan, future phases would see the addition of several new midfield concourses and a new south terminal.[54] A fourth runway (parallel to the existing runways 1 and 19 L&R) opened in 2008,[55] and development plans include a fifth runway to parallel the existing runway 12–30.[56] If this runway is built, the current runway will be re-designated as 12L-30R while the new runway will be designated 12R-30L. An expansion of the B concourse, used by many low-cost airlines as well as international arrivals, has been completed, and the building housing Concourses C and D will eventually be knocked down to make room for a more ergonomic building. Because Concourses C and D are temporary concourses, the only way to get to those concourses is via moving walkway from the Concourse C station which is built in the location of the future gates and Concourse D by mobile lounge from the main terminal.[57][58]

In the short term, United Airlines has constructed a 20,000 square foot (1,900 m2) buildout on Concourse C between gate C18 and the AeroTrain entrance for use as a Polaris Lounge for international passengers.[59] Further expansion plans include a new three-story 550,000 square foot (51,000 m2) south concourse building above the AeroTrain station for Concourse C,[58] to replace Concourse A regional gates built in 1999.[60]

Decades-old rules set by Congress that limit the number of takeoffs and landings, as well as distance of routes, at Reagan Airport were intended in part to keep more flights at Dulles. However, those rules have been weakened by Congress over the years, causing Dulles to lose 200,000 passengers to Reagan between 2011 and 2013.[9]

In 2022, it was reported that Dulles would include the largest airport-based solar and battery development in the U.S. as part of an agreement with Dominion Energy. The solar panels would cover more than 835 acres (338 ha) on land and would be sufficient to provide energy to more than 37,000 Northern Virginia homes during peak production.[61]

Meaning of IAD

Dulles originally used airport code DIA, the initials of Dulles International Airport. When handwritten, it was often misread as DCA, the code for Washington National Airport, so in 1968 Dulles's code was changed to IAD.[62]

Terminals

The airport's terminal complex consists of a main terminal (which includes four of the original gates, "Z" gates), and two parallel midfield terminal buildings: Concourses A/B and C/D. The entire terminal complex has 139 total gates: 123 gates with jetways and 16 hardstand locations[63] from which passengers can board or disembark using the airport's plane mate vehicles.[8]

Inter-terminal transportation

Conceived in early planning sessions in 1959, Dulles is one of a few remaining airports to utilize mobile lounges (also known as "plane mates" or "people movers"), now only used for transport to the International Arrivals Building as well as transport for Concourse D. They have all been given names based on the postal abbreviations of 50 states, e.g., VA, MD, AK.[64]

The Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority has gradually phased out the mobile lounge system for inter-terminal passenger movements in favor of the AeroTrain, an underground people mover which currently operates to all of the concourses except concourse D, with passenger tunnels remaining to concourses A and B. Plane mates remain in use to disembark international passengers and carry them to the International Arrivals Building, as well as to transport passengers to and from aircraft on the hard stands (i.e., those parked remotely on the apron without access to jet bridges).[65][66]

Main terminal

Dulles's iconic main terminal houses ticketing on the upper level, baggage claim and U.S. Customs and Border Protection on the lower level, and annexes for the International Arrivals Building for international passenger processing, as well as the four Z gates (used by Air Canada and United Express), various information kiosks and other support facilities. The main terminal was recognized by the American Institute of Architects in 1966 for its design concept; its roof is a suspended catenary providing a wide enclosed area unimpeded by any columns.[citation needed]

The main terminal was extended in 1996 to 1,240 feet (380 m)—Saarinen's original design length—which was slightly more than double its originally constructed length of 600 feet (180 m).[63] On September 22, 2009, an expansion to include the 41,400 square feet (3,850 m2) International Arrivals Building opened for customs and immigration processing with a capacity to process 2,400 passengers per hour.[67]

Also in September 2009, a 121,700 square feet (11,310 m2) central security checkpoint was added on a new security mezzanine level of the main terminal. This checkpoint replaced previous checkpoints which were located behind the ticketing areas,[68] however, travelers enrolled in TSA PreCheck and CLEAR still use this area to clear security.[69] A separate security checkpoint is available on the baggage claim level. Both security checkpoints connect to the AeroTrain, which links the main terminal with the A, B, and C concourses.

Midfield terminals

All airlines aside from Air Canada Express and United Express operate out of two linear satellite terminals. Each terminal is divided into two concourses, with the north terminal containing Concourses A and B, and the south terminal containing Concourses C and D.[citation needed]

Concourses A and B

Concourses A and B are located in the midfield terminal building closer to the main terminal. They are utilized by all non-United flights as well as a limited number of United Express flights. Concourse A has 47 gates, located in the eastern half of the north midfield terminal. It consists of a permanent ground-level set of gates designed for small planes and Unted Express flights, and several former Concourse B gates.[70] The concourse is primarily used for international flights. Air France and KLM have a lounge opposite gate A19, Etihad Airways operates a First and Business Class lounge across from gate A15, and Virgin Atlantic has a Clubhouse lounge adjacent to gate A31. Concourse A's AeroTrain station is located between gates A6 and A14.[citation needed]

Concourse B has 28 gates, located in the western half of the terminal. It is the first of the permanent elevated midfield concourses. Originally constructed in 1998 and designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and Hellmuth, Obata and Kassabaum, the B concourse contained 20 gates. In 2003, 4 additional gates were added to concourse B, followed by a 15-gate expansion in 2008.[71] In addition to the AeroTrain station located between gates B51 and B62, Concourse B also has an underground walkway to connect it to the main terminal. Concourse B is used by some international carriers, and is also utilized by all non-United domestic and Canada flights. The facility also includes a British Airways Galleries lounge adjacent to the AeroTrain station, a Lufthansa lounge between gates B49 and B51, and a Turkish Airlines lounge near gate B43.[72]

Concourses C and D

Concourses C and D are located in the south midfield terminal, and are used for United Airlines flights, including all mainline flights and most United Express regional flights (save for a few that use Concourse A).

These concourses were constructed in 1983 and designed by Hellmuth, Obata and Kassabaum. The two concourses have 22 gates each, numbered C1–C28 and D1–D32, with odd-numbered gates on the north side of the building and even numbered gates on the south side. Concourse C composes the eastern half of the terminal and Concourse D composes the western half.[73][74] The C/D concourses were given a face lift in 2006 which included light fixture upgrades, new paint finishes, new ceiling grids and tiles, heating and air conditioning replacement, and complete restroom renovations.[74]

While all gates in Concourses C/D can be utilized for both domestic and international departures, all United international arrivals are conducted at gates C1-C14. These gates contain two exit configurations depending on the arriving flight. Domestic passengers and international passengers from airports with U.S. customs pre-clearance exit directly into the concourse, while international arrivals from airports without border pre-clearance are redirected down a sterile corridor to U.S. Customs & Immigration. Passengers arriving from international destinations who are ending their journey at Dulles are then transported by mobile lounge to the International Arrivals Building, while passengers making onward connections are directed to a separate customs facility located on the ground floor of Concourse C. After being screened by TSA at a dedicated security checkpoint within the facility, these passengers then take escalators that deposit them in Concourse C near gate C7.[75]

A new and permanent C/D concourse (also called "Tier 2") is planned as part of the D2 Dulles Development Project. The new building is to include a three-level structure with 44 airline gates and similar amenities to Concourse B.[74] The concourse plan includes a dedicated mezzanine corridor with moving sidewalks to serve international passengers. The design and construction of the new C/D concourse has not been scheduled.[74] When built, it is planned that both terminals will be connected to the main terminal and other concourses via the AeroTrain. To that extent, the AeroTrain station at Concourse C was built at the location where the future Concourse C/D structure is proposed to be built, and is connected to the existing Concourse C via an underground walkway.[58] In April 2022, the Airport Authority published plans for a 14 gate Concourse E to be built atop the AeroTrain station with the purpose of replacing outdoor boarding areas at Concourse A. Construction is expected to cost between $500 million and $800 million and the airport is seeking $230 million grants from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill. [76]

Airline lounges

Since many major domestic and international airlines have a large presence at Washington Dulles, there are many airline lounges within the airport:

- Air France: Air France/KLM Lounge, A Concourse across from gate A22.[77]

- British Airways: BA Lounge with Concorde Dining for first class and Business class passengers, located opposite the Concourse B Transit station.[78]

- Capital One is constructing its second airport lounge at Dulles. It will be operated by a third-party hospitality company and is scheduled to open in 2022.[79]

- Etihad Airways: First and Business class lounge located opposite gate A15.[80]

- Lufthansa: Senator Lounge and Business Lounge, B Concourse at gate B51.[77]

- Turkish Airlines: Concourse B, near gate B41.[72]

- United Airlines: Three United Clubs in Concourse C (at gates C4, C7 and C17), and one in Concourse D at gate D8.[81] There is also a Polaris Lounge located directly across from gate C17.[82]

- Virgin Atlantic: Clubhouse, Concourse A across from gate A32.[83]

Airlines and destinations

Passenger carriers

Cargo carriers

| Airlines | Destinations |

|---|---|

| FedEx Express | Harrisburg, Indianapolis, Memphis, New York–JFK, Newark, Philadelphia, Jacksonville |

| FedEx Feeder | Newark |

| UPS Airlines | Louisville |

Statistics

Top destinations

| Rank | Airport | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 451,000 | Southwest, United | |

| 2 | 396,000 | Alaska, United | |

| 3 | 376,000 | Alaska, United | |

| 4 | 330,000 | Delta, Southwest, United | |

| 5 | 223,000 | United | |

| 6 | 220,000 | United | |

| 7 | 217,000 | Frontier, Southwest, United | |

| 8 | 214,000 | Alaska, Delta, United | |

| 9 | 206,000 | United | |

| 10 | 200,000 | American, United |

Airline market share

| Rank | Airline | Enplanements | Percent of market share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United Airlines | 2,899,449 | 70.42% |

| 2 | Delta Air Lines | 212,151 | 5.12% |

| 3 | American Airlines | 142,382 | 3.44% |

| 4 | Southwest Airlines | 85,013 | 2.05% |

| 5 | Alaska Airlines | 63,659 | 2.05% |

Annual traffic

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

| Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 19,797,329 | 2009 | 23,213,341 | 2019 | 24,817,677 |

| 2000 | 20,104,693 | 2010 | 23,741,603 | 2020 | 8,333,460 |

| 2001 | 18,002,319 | 2011 | 23,211,856 | 2021 | 15,006,955 |

| 2002 | 17,235,163 | 2012 | 22,561,521 | 2022 | 21,376,896 |

| 2003 | 16,950,381 | 2013 | 21,947,065 | 2023 | |

| 2004 | 22,868,852 | 2014 | 21,572,233 | 2024 | |

| 2005 | 27,052,118 | 2015 | 21,650,546 | 2025 | |

| 2006 | 23,020,362 | 2016 | 21,969,094 | 2026 | |

| 2007 | 24,737,528 | 2017 | 22,892,504 | 2027 | |

| 2008 | 23,876,780 | 2018 | 24,060,709 | 2028 |

Ground transportation

Roads

Washington Dulles is accessible via the Dulles Access Road/Dulles Greenway (State Route 267) and State Route 28. The Access Road is a toll-free, limited access highway owned by the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA) to facilitate car access to Washington Dulles from the Capital Beltway and Interstate 66.[143] After it opened, non-airport traffic between Washington and Reston became so heavy that a parallel set of toll lanes were added on the same right-of-way to accommodate non-airport traffic (Dulles Toll Road). However, the airport-only lanes are both less congested as well as toll-free. As of November 1, 2008, MWAA assumed responsibility from the Virginia Department of Transportation both for operating the Dulles Toll Road and for the construction of the Silver Line down its median. Route 28, which runs north–south along the eastern edge of the airport, has been upgraded to a limited access highway, with the interchanges financed through a property tax surcharge on nearby business properties. The Dulles Toll Road has been extended to the west to Leesburg as the Dulles Greenway.[citation needed]

Public transportation

Washington Metro service is available to Dulles via a station on the Silver Line.[144] Service began operation on November 15, 2022.[145]

Fairfax Connector bus routes 981 and 983 serve Washington Dulles, connecting to the Herndon–Monroe park & ride lot in Herndon, the Reston Town Center transit in Reston, the Wiehle–Reston East Metro station, and the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center Air and Space Museum.[citation needed] Formerly, the Metrobus 5A route served at the airport.

Megabus provides service from Dulles to Charlottesville and Blacksburg.

Washington Flyer has a monopoly to operate cabs from Washington Dulles Airport.[146] Uber and Lyft are popular modes of transport to and from the airport and MWAA receives a $4 fee per trip, which is included in the quoted fare.[147]

Accidents and incidents

- On January 21, 1970, the first commercial flight of the Boeing 747 was delayed, when an engine malfunction caused the aircraft in question to be temporarily grounded. Another 747, the Clipper Victor, was on standby, and flew the inaugural flight for Pan American Airways. The Clipper Victor would later be destroyed in the Tenerife airport disaster.[citation needed]

- There were three deaths during a nine-day air show held at Washington Dulles in conjunction with Transpo '72 (officially called the U.S. International Transportation Exposition, a $10 million event sponsored by the U.S. Department of Transportation, and attended by over one million visitors from around the world).

- On May 29, 1972, the third day of the show, the pilot of a Kite Rider (a variety of hang glider) was killed in a crash. This was to be the first of the three air deaths during the Air Show.[148][149]

- On June 3, 1972, a second death occurred at the Transpo '72 Air Show, during a sport plane pylon race. At 2:40 pm, during the second lap and near a turn about pylon 3, a trailing aircraft's (LOWERS R-1 N66AN) wing and propeller hit the right wing tip of a leading aircraft (CASSUTT BARTH N7017). The right wing immediately sheared off the fuselage, and the damaged aircraft crashed almost instantly, killing the 29-year-old pilot, Hugh C. Alexander. He was a professional Air Racer with over 10,200 hours.[150][151]

- On June 4, 1972, during the last day of the 9-day Transpo '72 Air Show, the U.S. Air Force Thunderbirds experienced their first fatal crash at an air show. Major Joe Howard flying Thunderbird 3 was killed when his F-4E-32-MC Phantom II, 66-0321, lost power during a vertical maneuver. The pilot broke out of formation just after he completed a wedge roll and was ascending at around 2,500 feet (760 m) AGL. The aircraft staggered and descended in a flat attitude with little forward speed. Although Major Howard ejected as the aircraft fell back to earth from about 1,500 feet (460 m) tail first, and descended under a good canopy, winds blew him into the fireball ascending from the blazing crash site. The parachute melted and the pilot plummeted 200 feet (61 m), sustaining fatal injuries.[152]

- On December 1, 1974, while diverting to Washington Dulles, TWA Flight 514 crashed onto the western slope of Mount Weather.[153] All 85 passengers and seven crew members were killed on impact.

- Air France Concorde incidents of 1979:

- On June 14, 1979, the number 5 and 6 tires on an Air France Concorde blew out during takeoff. Shrapnel thrown from the tires and rims damaged number 2 engine, punctured three fuel tanks, severed several hydraulic lines and electrical wires, in addition to tearing a large hole on the top of the wing, over the wheel well area.[154]

- On July 21, 1979, one month after the above tire incident, another Air France Concorde blew several of its landing gear tires during takeoff. After that second incident the "French director general of civil aviation issued an air worthiness directive and Air France issued a Technical Information Update, each calling for revised procedures. These included required inspection of each wheel/tire for condition, pressure and temperature prior to each take-off. In addition, crews were advised that landing gear should not be raised when a wheel/tire problem is suspected."[154]

- On November 15, 1979 American Airlines Flight 444 diverted to Dulles Airport instead of its scheduled destination of Washington National Airport due to the detonation of a small bomb. The bomb detonated incompletely in the cargo hold of the aircraft and resulted in 12 passengers being treated for smoke inhalation. It was later determined this was the third bombing perpetrated by Theodore John Kaczynski aka "The Unabomber." Ultimately it was the involvement of the aircraft in his bombing targets that resulted in the FBI becoming involved with the investigation and search for the "Unabomber."[citation needed]

- On July 20, 1988, a Fairways Corp. de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter stalled and crashed after takeoff. The sole occupant, the pilot, was killed.[155]

- On June 18, 1994, a Learjet 25 operated by Mexican carrier TAESA crashed in trees while approaching the airport from the south. 12 people died.[156] The passengers were planning to attend the 1994 FIFA World Cup soccer games being staged in Washington, D.C.

- On September 11, 2001, American Airlines Flight 77 took off from Dulles Airport out of Gate D-26 bound for Los Angeles. It was deliberately crashed into the Pentagon at 9:37 am EDT by Al-Qaeda terrorists, killing everyone on board.[citation needed]

See also

- Busiest airports in the United States by international passenger traffic

- List of thin shell structures

- Thin-shell structure

- List of tallest air traffic control towers in the United States

References

- ^ "Lancaster's Hometown Airline to Serve Washington-Dulles". Aviation Pros. April 19, 2021.

- ^ a b FAA Airport Form 5010 for IAD PDF

- ^ "Dulles Air Traffic Statistics". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. January 2023. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ "Dulles International Airport". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ^ a b "JFK, Eisenhower dedicated airport". The Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. November 17, 1962. p. 1A.

- ^ a b "$110 million Dulles airport is dedicated". The Bulletin. (Oregon). UPI. November 17, 1962. p. 1.

- ^ "Washington-Dulles International Airport data at skyvector.com". skyvector.com. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Facts About Washington Dulles International Airport". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ a b c Aratani, Lori (November 27, 2014). "Dulles International Airport struggles to find its footing". The Washington Post.

- ^ "U.S. International Air Passenger and Freight Statistics Report". Office of the Assistant Secretary for Aviation and International Affairs, U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Washington Dulles International Airport (IAD) Air Traffic Statistics". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ "Preliminary CY 2012 Enplanements" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Air Service Maps – IAD". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Archived from the original on December 16, 2010. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ^ "Dulles International - Nonstop Destinations". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ "After years-long slump, Dulles International Airport bounces back". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Dulles International Airport pulled ahead of Reagan National in 2018". WTOP. February 20, 2019. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- ^ "MWAA Air Traffic Statistics" (PDF), Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority, December 1, 2018, retrieved August 16, 2019

- ^ a b c Scheel, Eugene. "History of Dulles Airport". Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ "History of Washington Dulles International Airport". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Greenfield, Heather (November 17, 2002). "'Visionary' Dulles Airport hits 40". The Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. Associated Press. p. B1.

- ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Virginia: Loudoun County". www.airfields-freeman.com. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ Tom (January 21, 2014). "Opening Dedication Ceremony of Dulles Airport in 1962". Ghosts of DC. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ "History of Washington Dulles International Airport". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ^ George, Justin; Laris, Michael; Aratani, Lori (November 15, 2022). "Silver Line extension opens, adding six stations, Dulles connection after years of delays". The Washington Post.

- ^ Davis, J.W. (April 17, 1966). "Dulles Airport: Its future keeps being postponed". Eugene Register-Guard. Oregon. p. 10A.

- ^ FAA Air Traffic Activity, Calendar Year 1965 p42

- ^ Aviation Daily 23 Feb 1971 p. 291

- ^ "President's wife christens giant jet". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. January 15, 1970. p. 5A.

- ^ "Pat christens plane". Pittsburgh Press. UPI photo. January 15, 1970. p. 1.

- ^ "2 Concordes zip supersonic travel age into U.S." Pittsburgh Press. UPI. May 24, 1976. p. 1.

- ^ "Concorde lands in U.S." Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). (AP photo). May 25, 1976. p. 1.

- ^ Tom (January 30, 2012). "First Commercial Concorde Flight Lands at Dulles". Ghosts of DC. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ "Space Shuttle Pavilion". IntrepidMuseum.org. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ "Tribute to Eisenhower". The New York Times. Reuters. January 25, 1990. Retrieved June 3, 2011.see also, 101st Congress, S.J.RES.239.

- ^ "Blackbird Records". SR-71 Online. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ "United Airlines". Century-of-flight.net. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ "United Express moves to Concourse A at Dulles International Airport". United.com. Archived from the original on April 24, 2006. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ Coombs, Joe (February 7, 2008). "Passenger numbers up at Dulles International, Reagan National airports". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ Tom (June 13, 2012). "Space Shuttle Discovery Flies Over Washington". Ghosts of DC. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ Lufthansa starts 747-8 flights to Dulles – Washington Business Journal. Bizjournals.com (2012-06-01). Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ^ Ethiopian Airlines Inaugurates 787 Dreamliner Airplane at Washington Dulles International Airport. ET African Journeys (2012-08-17). Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ^ Mutzabaugh, Ben (January 15, 2016). "Emirates will fly A380 to D.C. after United drops Dubai route". USA Today.

- ^ GOAA. "North Terminal Enhancements – Orlando International Airport (MCO)". Orlando International Airport (MCO). Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ Pallini, Thomas (May 17, 2018). "Volaris Costa Rica Inaugurates Washington Route, Marks New Chapter for Dulles". Airline Geeks. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ "Cathay Pacific to launch Washington DC service with the Airbus A350-1000". news.cathaypacific.com.

- ^ Ben (October 9, 2018). "Cathay Pacific Downgrades Washington Route Just Weeks After Launch". One Mile at a Time. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ Gibertini, Vanni (May 3, 2019). "Alitalia Launches Rome-Washington Flight as Financial Struggles Linger". AirlineGeeks.com. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Pallini, Thomas (February 25, 2019). "EgyptAir Adds Washington-Dulles Route with 787 Dreamliner". AirlineGeeks.com. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ "United Airlines Announces New Nonstop Service Between Washington, D.C. and Tel Aviv". United Hub. August 2, 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ "Lancaster's Hometown Airline to Serve Washington-Dulles". April 19, 2021.

- ^ "Passenger Walkway to Concourses A and B Fact Sheet" (PDF). Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "Dulles Development: Main Terminal Improvement Fact Sheet" (PDF). Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Aerotrain – How the System Works" (PDF). Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Weiss, Eric M. (August 19, 2008). "Dulles Updates Its People Movers". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "D2 Projects: Fourth Runway". Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority. 2009. Archived from the original on September 29, 2010. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "D2 Projects: Future Fifth Runway". Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority. 2009. Archived from the original on September 30, 2010. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Fox, Peggy (January 25, 2010). "Dulles Airport To Open AeroTrain". 9 News Now. WUSA. Archived from the original on December 8, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c "D2 Projects: AeroTrain System". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Archived from the original on November 13, 2007. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Russell, Edward (December 10, 2018). "United to invest at least $34m at Washington Dulles". Flight Global. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ "Dulles Airport's Ambitious Expansion Continues with New United Concourse". July 7, 2021.

- ^ "Dulles solar farm would be the nation's largest at an airport". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ Crohn, Nick; Fisher, Lynn (March 24, 2015). "LAX. IAD. ARN. WTF? The strange stories behind airports' three-letter abbreviations". Slate. Slate Group. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ a b "Facts About Washington Dulles International Airport". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. 2010. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Komons, Nick (August 1, 1989). "Air Progress". Air Progress: 65.

- ^ Aryanpur, Arianne (February 2, 2006). "At Dulles, The Tarmac Is Their Turf". The Washington Post. p. VA16. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- ^ Miroff, Nick (September 14, 2006). "Airport's Future Is on Rails". The Washington Post. p. B01. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- ^ Freeman, Sholnn (September 22, 2009). "Elbow Room Expands for International Arrivals". The Washington Post. p. B2.

- ^ "New Passenger Security Screening Areas Open at Dulles International Airport Tomorrow" (PDF). Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority Office of Public Affairs. September 14, 2009. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "Security Information". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. July 2, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ^ "Aerotrain has Opened". Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority. 2010. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "D2 Dulles Development: Concourse B Expansion" (PDF). Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Klint, Matthew (September 2016). "Photo Tour: Turkish Airways Lounge Washington Dulles".

- ^ Kidder Smith, G. E. (2000). Source Book of American Architecture: 500 Notable Buildings from the 10th Century to the Present. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 448–449. ISBN 978-1568982540. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "D2 Projects – Concourse C/D". Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority. 2011. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ >"Why I Love International Connections at Washington Dulles". 2016. Archived from the original on March 30, 2022. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ "Dulles International Airport Proposes New 14-Gate Concourse".

- ^ a b "Main Terminal" (PDF). Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority. July 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 16, 2010. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "Lounge review: BA Galleries Lounge, Washington Dulles". Business Traveller.

- ^ "Capital One Moves In on AmEx Turf With Push Into Airport Lounges". Bloomberg News. April 19, 2021.

- ^ "Worldwide lounges". Qatar Airways. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "United Club & Airport Lounges". United Airlines. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ "Now Open: United Polaris Lounge Washington Dulles". October 21, 2021.

- ^ "Washington". Virgin Atlantic. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "Timetables". Aer Lingus. Dublin: International Airlines Group.

- ^ "Destinations". Aeroflot.

- ^ Chan, Kenneth (February 23, 2023). "Air Canada to launch new route between Vancouver and Washington, DC". Daily Hive. Vancouver. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "Flight Schedules". Air Canada.

- ^ "Destinations". Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "Flight Status". Air France. Paris: Air France-KLM.

- ^ "Time Table – Air India". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Airlines, Alaska (January 30, 2023). "Alaska Airlines expands our San Diego network with new coast-to-coast nonstops".

- ^ "Flight Timetable". May 6, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ "Allegiant schedule". Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "Timetables [International Routes]". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "Flight schedules and notifications". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "American Airlines revises Austin-Washington service in NW22". AeroRoutes. October 5, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ "Austrian Timetable". Austrian Airlines.

- ^ a b "Check itineraries". Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ "Avianca strengthens connectivity from Central America with the operation of routes to the United States". Periódico Digital (in Spanish). September 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ "Timetables". British Airways.

- ^ "Timetable | Brussels Airlines". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Flight Schedule". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "FLIGHT SCHEDULES". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Delta Resumes New York LaGuardia – Washington Dulles Service From Nov 2022". Aeroroutes. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ "EgyptAir Timetable". Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ "Flight Schedules". Emirates.

- ^ "Schedule – Fly Ethiopian". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Flight Timetables". Etihad Airways.

- ^ "Flight times - Iberia". Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Flight Schedule". Icelandair.

- ^ https://www.ita-airways.com/it_it/offerte/tutte-le-offerte/washington-san-francisco.html

- ^ "View the Timetable". KLM. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Flight Status and Schedules". Korean Air.

- ^ "Timetable – Lufthansa Canada". Lufthansa. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Norse Atlantic Airways announces full summer 2023 schedule from London with the addition of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington, D.C. and Boston". Norse Atlantic Airways (Press release). Cision. February 28, 2023. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ "Where we fly". Norse Atlantic Airways. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ "StackPath". August 23, 2022.

- ^ "Interactive Route Map". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Flight timetable". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Flight Schedules". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Flight Schedule". Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "Timetable – SAS". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Destinations". Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ "Check Flight Schedules". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Tailwind Air's Seaplanes Cut Travel Times Between Washington, DC - IAD and Manhattan, NYC in Half". Tailwind. New York: Tailwind Air.

- ^ "All Destinations". TAP Portugal.

- ^ "Online Flight Schedule". Turkish Airlines.

- ^ United to Become First Airline to Fly Nonstop Between Washington D.C. and Cape Town United. PRNewswire. July 28, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2023

- ^ "United To Return To Prague & Stockholm While Starting Washington-Berlin Flights". Simpleflying.com. July 21, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ "United Adds Washington – Calgary Service in NS23". Aeroroutes. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "United Airlines to resume seasonal flights between Washington and San Jose (SJO)". Aviacionline. August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ "Timetable". Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Timetable". Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "Interactive flight map". Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Casey, David. "Volaris El Salvador Granted Final Approval For US Routes". Routesonline. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ "WESTJET NS23 NORTH AMERICA NETWORK CHANGES – 12FEB23". AeroRoutes. February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ "Ethiopian Airlines Moves North American Intermediate Stop to Dublin from May 2015". Airlineroute.net. April 15, 2015. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ "Washington, DC: Dulles International (IAD)- Scheduled Services except Freight/Mail". Transtats.bts.gov. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ "International_Report_Passengers | Department of Transportation – Data Portal". data.transportation.gov. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ "2020 COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2021.

- ^ "Monthly Air Traffic Summary Report". Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority. February 15, 2023. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Total cargo (Freight, Express, & Mail).

- ^ "Dulles Toll Road". Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ "Dulles International Airport". Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority. 2011. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- ^ "Metro customers invited to ride the first passenger train to six new Silver Line stations". wmata.com (Press release). WMATA. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ^ "End the Dulles Taxi Monopoly!". View from the Wing. July 17, 2009. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "DC's New Rules for Uber Airport Pickups Aren't Great For Riders". DC Inno. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "Kite Rider Killed in Crash At Transpo 72 Air Show". The New York Times. May 30, 1972.

- ^ Tom (March 6, 2012). "Three Things You Didn't Know About Dulles Airport". Ghosts of DC. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ "NTSB Aviation Query NYC72AN147 N66AN".

- ^ "NTSB Aviation Query NYC72AN147 N7017".

- ^ USAF Aircraft Accidents – Life Sciences Aspects, April–June 1972. Norton AFB, California: Directorate of Aerospace Safety, Air Force Inspection and Safety Center. pp. 59–60.

- ^ Shaw, Adam (1977). Sound of Impact: The Legacy of TWA Flight 514. New York City: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-65840-5.

- ^ a b "Safety Recommendations" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. November 9, 1981. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 200 N7267 Washington-Dulles International Airport, DC (IAD)". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ "Safety Recommendation" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. April 3, 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 26, 2009. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

External links

- Official website

- Footage of the Dedication of Dulles International Airport in 1962

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective December 26, 2024

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KIAD

- ASN accident history for IAD

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KIAD

- FAA current IAD delay information

- Dulles International Airport

- Washington metropolitan area

- Airports in Virginia

- Eero Saarinen structures

- Concrete shell structures

- Transportation in Loudoun County, Virginia

- Transportation in Fairfax County, Virginia

- Modernist architecture in Virginia

- Airports established in 1962

- Buildings and structures in Loudoun County, Virginia

- 1962 establishments in Virginia

- Googie architecture

- Skidmore, Owings & Merrill buildings

- Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority

- Suspended structures