Kaithi

| Kaithī 𑂍𑂶𑂟𑂲 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 16th–mid 20th century |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Awadhi, Bhojpuri, Hindustani, Magahi, Nagpuri, Maithili |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Kthi (317), Kaithi |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Kaithi |

| U+11080–U+110CF | |

[a] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is debated. | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

Kaithi (𑂍𑂶𑂟𑂲) is a historical Brahmic script that was used widely in parts of Northern and Eastern India, primarily in the present-day states of Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Bihar. In particular, it was used for writing legal, administrative and private records.[1] It was used for a variety of Indo-Aryan languages, including Awadhi, Bhojpuri, Hindustani, Magahi, and Nagpuri.

Etymology

Kaithi script derives its name from the word Kayastha, a social group of India that traditionally consists of administrators and accountants.[2] The Kayastha community was closely associated with the princely courts and British colonial governments of North India and were employed by them to write and maintain records of revenue transactions, legal documents and title deeds; general correspondence and proceedings of the royal courts and related bodies.[3] The script used by them acquired the name Kaithi.[citation needed]

History

Documents in Kaithi are traceable to at least the 16th century. The script was widely used during the Mughal period. In the 1880s, during the British Raj, the script was recognised as the official script of the law courts of Bihar. Kaithi was the most widely used script of North India west of Bengal. In 1854, 77,368 school primers were in Kaithi script, as compared to 25,151 in Devanagari and 24,302 in Mahajani.[4] Among the three scripts widely used in the 'Hindi Belt', Kaithi was widely perceived to be neutral, as it was used by both Hindus and Muslims alike for day-to-day correspondence, financial and administrative activities, while Devanagari was used by Hindus and Persian script by Muslims for religious literature and education. This made Kaithi increasingly unfavorable to the more conservative and religiously inclined members of society who insisted on Devanagari-based and Persian-based transcription of Hindi dialects. As a result of their influence and due to the wide availability of Devanagari type as opposed to the incredibly large variability of Kaithi, Devanagari was promoted, particularly in the Northwest Provinces, which covers present-day Uttar Pradesh.[5] Kaithi was also nicknamed "Shikasta Nagari" by analogy with Shikasta Nastaliq, because the relationship of Kaithi to Devanagari was perceived as akin to the relationship between the widely used dot-less Shikasta Nastaliq of the time and the more formal printed Nastaliq scripts, which used dotted letters and fuller, less abbreviated letter forms.

In the late 19th century, John Nesfield in Oudh, George Campbell of Inverneill in Bihar and a committee in Bengal all advocated for the use of Kaithi script in education.[6] Many legal documents were written in Kaithi, and from 1950 to 1954 it was the official legal script of Bihar district courts. However, it was opposed by Brahmin elites and phased out. Present day Bihar courts struggle to read old Kaithi documents.[7]

Classes

On the basis of local variants Kaithi can be divided into three classes viz. Bhojpuri, Magahi and Trihuti.[8][9]

Bhojpuri

This was used in Bhojpuri speaking regions and was considered as the most legible style of Kaithi.[8]

Magahi

Native to Magah or Magadh it lies between Bhojpuri and Trihuti.[8]

Tirhuti

It was used in Maithili speaking regions and was considered as the most elegant style.[8]

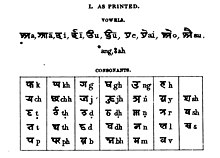

Consonants

All Kaithi consonants have an inherent a vowel:

| VOICELESS PLOSIVES | VOICED PLOSIVES | NASALS | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaspirated | Aspirated | Unaspirated | Aspirated | ||||||||||

| Letter | Trans. | IPA | Letter | Trans. | Letter | Trans. | IPA | Letter | Trans. | Letter | Trans. | IPA | |

| Velar | 𑂍 | k | /k/ | 𑂎 | kh | 𑂏 | g | /ɡ/ | 𑂐 | gh | 𑂑 | ṅ | /ŋ/ |

| Palatal | 𑂒 | c | /c/ | 𑂓 | ch | 𑂔 | j | /ɟ/ | 𑂕 | jh | 𑂖 | ñ | /ɲ/ |

| Retroflex | 𑂗 | ṭ | /ʈ/ | 𑂘 | ṭh | 𑂙 | ḍ | /ɖ/ | 𑂛 | ḍh | 𑂝 | ṇ | /ɳ/ |

| 𑂚 | ṛ | /ɽ/ | 𑂜 | ṛh | |||||||||

| Dental | 𑂞 | t | /t/ | 𑂟 | th | 𑂠 | d | /d/ | 𑂡 | dh | 𑂢 | n | /n/ |

| Labial | 𑂣 | p | /p/ | 𑂤 | ph | 𑂥 | b | /b/ | 𑂦 | bh | 𑂧 | m | /m/ |

| Palatal | Retroflex | Dental | Labial | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letter | Trans. | IPA | Letter | Trans. | IPA | Letter | Trans. | IPA | Letter | Trans. | IPA | ||

| Sonorants | 𑂨 | y | /j/ | 𑂩 | r | /r/ | 𑂪 | l | /l/ | 𑂫 | v | /ʋ/ | |

| Sibilants | 𑂬 | ś | /ɕ/ | 𑂭 | ṣ | /ʂ/ | 𑂮 | s | /s/ | ||||

| Other | |||||||||||||

| 𑂯 | h | /h/ | |||||||||||

Vowels

Kaithi vowels have independent (initial) and dependent (diacritic) forms:

| Trans. | Letter | Diacritic | Shown with k | Trans. | Letter | Diacritic | Shown with k | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guttural | a | 𑂃 | 𑂍 | ā | 𑂄 | 𑂰 | 𑂍𑂰 | |

| Palatal | i | 𑂅 | 𑂱 | 𑂍𑂱 | ī | 𑂆 | 𑂲 | 𑂍𑂲 |

| Rounded | u | 𑂇 | 𑂳 | 𑂍𑂳 | ū | 𑂈 | 𑂴 | 𑂍𑂴 |

| Palatoguttural | e | 𑂉 | 𑂵 | 𑂍𑂵 | ai | 𑂊 | 𑂶 | 𑂍𑂶 |

| Labioguttural | o | 𑂋 | 𑂷 | 𑂍𑂷 | au | 𑂌 | 𑂸 | 𑂍𑂸 |

Diacritics

Several diacritics are employed to change the meaning of letters:

| Diacritic | Name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| 𑂀 | chandrabindu | A chandrabindu denotes nasalisation although it is not normally used with Kaithi.[3] |

| 𑂁 | anusvara | An anusvara in Kaithi represents true vowel nasalisation.[3] For example, 𑂍𑂁, kaṃ. |

| 𑂂 | visarga | Visarga is a Sanskrit holdover originally representing /h/. For example, 𑂍𑂂 kaḥ.[3] |

| 𑂹 | halanta | A virama removes a consonant's inherent a and in some cases forms consonant clusters. Compare 𑂧𑂥 maba with 𑂧𑂹𑂥 mba.[10] |

| 𑂺 | nuqta | A nuqta is used to extend letters to represent non-native sounds. For example, 𑂔 ja + nuqta = 𑂔𑂺, which represents Arabic zayin.[3] |

Punctuation

Kaithi has several script-specific punctuation marks:

| Sign | Description |

|---|---|

| 𑂻 | The abbreviation sign is one method of representing abbreviations in Kaithi.[3] For example, 𑂪𑂱𑂎𑂱𑂞𑂧 can be abbreviated as 𑂪𑂲𑂻.[3] |

| | The number sign is used with digits for enumerated lists and numerical sequences.[3] It can appear above, below, or before a digit or sequence of digits.[3] For example, १२३. |

| 𑂼 | The enumeration sign is a spacing version of the number sign.[10] It always appears before a digit or sequence of digits (never above or below). |

| 𑂾 | The section sign indicates the end of a sentence.[10] |

| 𑂿 | The double section sign indicates the end of a larger section of text, such as a paragraph.[10] |

| 𑃀 | Danda is a Kaithi-specific danda, which can mark the end of a sentence or line. |

| 𑃁 | Double danda is a Kaithi-specific double danda. |

General punctuation is also used with Kaithi:

- + plus sign can be used to mark phrase boundaries

- ‐ hyphen and - hyphen-minus can be used for hyphenation

- ⸱ word separator middle dot can be used as a word boundary (as can a hyphen)

Digits

Kaithi uses stylistic variants of Devangari digits. It also uses common Indic number signs for fractions and unit marks.[10]

Unicode

Kaithi script was added to the Unicode Standard in October 2009 with the release of version 5.2.

The Unicode block for Kaithi is U+11080–U+110CF:

| Kaithi[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1108x | 𑂀 | 𑂁 | 𑂂 | 𑂃 | 𑂄 | 𑂅 | 𑂆 | 𑂇 | 𑂈 | 𑂉 | 𑂊 | 𑂋 | 𑂌 | 𑂍 | 𑂎 | 𑂏 |

| U+1109x | 𑂐 | 𑂑 | 𑂒 | 𑂓 | 𑂔 | 𑂕 | 𑂖 | 𑂗 | 𑂘 | 𑂙 | 𑂚 | 𑂛 | 𑂜 | 𑂝 | 𑂞 | 𑂟 |

| U+110Ax | 𑂠 | 𑂡 | 𑂢 | 𑂣 | 𑂤 | 𑂥 | 𑂦 | 𑂧 | 𑂨 | 𑂩 | 𑂪 | 𑂫 | 𑂬 | 𑂭 | 𑂮 | 𑂯 |

| U+110Bx | 𑂰 | 𑂱 | 𑂲 | 𑂳 | 𑂴 | 𑂵 | 𑂶 | 𑂷 | 𑂸 | 𑂹 | 𑂺 | 𑂻 | 𑂼 | | 𑂾 | 𑂿 |

| U+110Cx | 𑃀 | 𑃁 | 𑃂 | | ||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ^ King, Christopher R. 1995. One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Grierson, George A. 1899. A Handbook to the Kaithi Character. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pandey, Anshuman (6 May 2008). "L2/08-194: Proposal to Encode the Kaithi Script in ISO/IEC 10646" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Rai, Alok. "Hindi Nationalism", p. 13

- ^ General Report on Public Instruction in the Bengal Presidency, p. 103.

- ^ Rai, Alok (2007). Hindi Nationalism (Reprint ed.). London: Sangam Books. p. 51. ISBN 978-81-250-1979-4.

- ^ "कहीं पन्नों में दफन न हो जाए कैथी". inextlive (in Hindi). 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d Grierson, G.A. (1881). A Handbook to the Kayathi Character. Calcutta: Thacar Spink and Co. p. 4.

- ^ Grierson, G.A. (1902). Linguistic Survey of India, Vol. V, Part II.

- ^ a b c d e "The Unicode Standard, Chapter 15.2: Kaithi" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. March 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.