Sotho people

King Moshoeshoe I, founder of the Southern Basotho Nation of Lesotho, with his Ministers. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 7,254,315 (2023 est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 5,103,205 | |

| 2,130,110 | |

| 11,000 | |

| 6,000 | |

| 4,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Sesotho | |

| Religion | |

| African traditional religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pedi people, Tswana and Lozi | |

| Sotho | |

|---|---|

| Person | Mosotho |

| People | Basotho |

| Language | Sesotho |

| Country | Lesotho |

The Sotho (/ˈsuːtuː/)[1] people, also known as the Basuto or Basotho (/bæˈsuːtuː/), are a Bantu nation native to southern Africa. Basotho have inhabited the region of Lesotho, South Africa since around the fifth century CE. They have split into different clans over time, as result of mfecane and colonialism. There are 3 types of Basotho groupings in Southern Africa viz The Southern Sotho found in Free State and Lesotho, Northern Sotho found in Limpopo, Gauteng and Mpumalanga and Western Sotho better known as Tswana found in the present day Northern West and Botswana. The British and the Boers, [Dutch descendants] divided Basotho land amongst themselves in the late 1800s. Lesotho was created by the settlers in the 1869 Convention of Aliwal North following the conflict over land between Moshoeshoe I and the Dutch descendants.

19th century

The great King Moshoeshoe was the first son of Mokhachane,[3] a minor chief of the Bamokoteli sub-clan of the Basotho people.[4] He was born at Menkhoaneng in Botha-bothe, Lesotho as Lepoqo. Moshoeshoe and his age mates went to initiation school and he got the name Letlama meaning strong bond. During his youth just after initiation, he was very brave, diplomatic and once organised a cattle raid against Ramonaheng and captured several herds to prove his genius methods. As was the tradition, he composed a poem praising himself where, amongst the words he used to refer to himself, said he was "like a razor which has shaved all Ramonaheng's beards", referring to his successful raid. In Sesotho language, a razor is said to make a "shoe...shoe..." sound, and after that he was affectionately called Moshoeshoe: "the shaver". He also referred himself as the person of Kali, thus showed that he was a descendant of the Great Kali or Monaheng who is said to be the ancestor of most Bakoena people in Lesotho with the exception of the senior Bamolibeli. The paramount, famous King of Basotho, king Moshoeshoe and his followers, mostly the Bakoena Bamokoteli, some Bafokeng from his maternal side and other relations as well as some clans including the Amazizi, established his village at Butha-Buthe, where his settlement and reign coincided with the growth in power of the well-known Zulu King, Shaka and what is known as the Difaqane 'time of troubles' (still known as 'Difaqane'). During the early 19th century Shaka raided many other smaller Zulu chiefdoms along the eastern coast of Southern Africa (modern day Kwa-Zulu Natal), incorporating parts of them into his steadily growing Zulu chiefdom. Various small Zulu clans were forced to flee the Zulu chief. An era of great wars of calamity followed, known as the time of troubles/Difaqane. It was marked by the intended aggression between the Basotho and Zulu Nations. However Shaka never attempted the attacks on the invincible Great King Moshoeshoe as the strong growing intelligent Basotho nation was conquering a series of wars against the Boers and the British. The strong and heavily armed Basotho nation manipulated the British to obtain powerful weapons, intensive military training, foreign advisor (Eugène Casalis) and many mission stations .The undisputed Basotho Nation and Great King of Basotho defeated both the Boers and the British in all the Free State Wars which were classified as Basotho, Seqiti and Senekal wars. The Great King Moshoeshoe would give everyone fair conditions for maintaining peaceful coexistence and then beat them back when they rebelled. The white settlers’ attacks also influenced King Moshoeshoe to restructure and use his diplomatic skills to expand his settlement to the Qiloane plateau. The name was later changed to Thaba Bosiu or "mountain at night" because it was believed to grow during the night and shrink during day. It proved to be an impassable stronghold against enemies. The paramount Basotho Nation remained the only nation to conquer all the Free State Wars against the Boers and the British in the history of South Africa and Africa under the leadership of the renowned Great King Moshoeshoe1.

20th century

BThe most significant role Moshoeshoe played as a diplomat was his acts of friendship towards his beaten enemies. He provided land and protection to various people and this strengthened the growing intelligent Basotho nation. His influence and followers grew with the integration of a number of refugees and victims of the wars of calamity.[citation needed] By the latter part of the 19th century, the great King Moshoeshoe established the nation of the Basotho, in Basutoland. He was popularly known as Morena e Moholo/morena oa Basotho (Great King/King of the Basotho). Guns were introduced with the arrival of the Dutch from the Cape Colony and Moshoeshoe determined that he needed these and a white advisor. From other tribes, he heard of the benefits missionaries brought. By chance, three representatives of the Society arrived in the heart of southern Africa: Eugène Casalis [fr], Constant Gosselin [fr] and Thomas Arbousset [fr]. Moshoeshoe brought them to his kingdom. Later Roman Catholic Missionaries were to have a great influence on the shape of Basotho History (the first being, Bishop M.F. Allard O.M.I. and Fr. Joseph Gerard O.M.I.). From 1837 to 1855 Casalis played the role of Moshoeshoe's Foreign Advisor. With his knowledge of the non-African world, he was able to inform and advise the king in his dealings with hostile foreigners. He also served as an interpreter for Moshoeshoe in his dealings with white people, and documented the Sesotho language as the first African language to be translated into English. In the late 1830s, Boer trekkers from the Cape Colony showed up on the western borders of Basutoland and subsequently claimed land rights. The trekkers' pioneer in this area was Jan de Winnaar, who settled in the Matlakeng area in May–June 1838. As more farmers were moving into the area they tried to colonise the land between the two rivers, even north of the Caledon, claiming that it had been "abandoned" by the Sotho people. Moshoeshoe, when hearing of the trekker settlement above the junction, stated that "... the ground on which they were belonged to me, but I had no objections to their flocks grazing there until such time as they were able to proceed further; on condition, however, that they remained in peace with my people and recognized my authority." Eugène Casalis later remarked that the trekkers had humbly asked for temporary rights while they were still few in number, but that when they felt "strong enough to throw off the mask" they went back on their initial intention. The next 30 years were marked by conflicts.

Demographics

The allure of urban areas has not diminished, and internal migration continues today for many black people born in Lesotho and other Basotho heartlands.[2] Generally, employment patterns among the Basotho follow the same patterns as broader South African society. Historical factors cause unemployment among the Basotho and other Black South Africans to remain high.[3]

Percent of Sesotho speakers across South Africa:[4]

- Gauteng Province: 13.1%

- Atteridgeville: 12.3%

- City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality: 9.6%

- Soweto: 15.5%

- Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality: 10.02%

- Katlehong: 22.4%

- Sedibeng District Municipality: 46.7%

- West Rand District Municipality: 10.8%

- Midvaal Local Municipality: 27.9%

- Free State Province: 64.2%

- Bloemfontein: 33.4%

Language

The language of the Basotho is referred to as Sesotho,[5] less commonly known as Sesotho sa borwa.[6] Some texts may refer to Sesotho as "Southern Sotho" to differentiate it from Northern Sotho, also called Sepedi.

Sesotho is the first language of 1.5 million people in Lesotho, or 85% of the population.[7] It is one of the two official languages in Lesotho, the other being English.[7] Lesotho enjoys one of Africa's highest literacy rates, with 59% of the adult population being literate, chiefly in Sesotho.[8]

Sesotho is one of the eleven official languages of South Africa.[5] According to the South African National Census of 2011, almost 4 million people speak Sesotho as a first language, including 62% of Free State inhabitants.[9] Approximately 13.1% of the residents of Gauteng speak Sesotho as a first language.[4] In the North West Province, 5% of the population speak Sesotho as a first language, with a concentration of speakers in the Maboloka region.[9] Three percent of Mpumalanga's people speak Sesotho as a first language, with many speakers living in the Standerton area.[9] Two percent of the residents of the Eastern Cape speak Sesotho as a first language, though they are located mostly in the northern part of the province.[9]

Aside from Lesotho and South Africa, 60,000 people speak Silozi (a close relative of Sesotho) in Zambia.[10] Additionally, a few Sesotho speakers reside in Botswana, Eswatini and the Caprivi Strip of Namibia.[10] No official statistics on second language usage are available, but one conservative estimate of the number of people who speak Sesotho as a second (or later) language is 5 million.[10]

Sesotho is used in a range of educational settings both as a subject of study and as a medium of instruction.[8] It is used in its spoken and written forms in all spheres of education, from preschool to doctoral studies.[8] However, the number of technical materials (e.g. in the fields of commerce, information technology, law, science, and math) in the language is still relatively small.[8]

Sesotho has developed a sizable media presence since the end of apartheid. Lesedi FM is a 24-hour Sesotho radio station run by the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), broadcasting solely in Sesotho. There are other regional radio stations throughout Lesotho and the Free State.[8] Half-hour Sesotho news bulletins are broadcast daily on the SABC free-to-air channel SABC 2. Independent TV broadcaster eTV also features a daily half-hour Sesotho bulletin. Both SABC and the eTV group produce a range of programs that feature some Sesotho dialogue.

In Lesotho, the Lesotho National Broadcasting Service broadcasts to South Africa via satellite pay-TV provider, DStv.

Most newspapers in Lesotho are written in Sesotho or both Sesotho and English. There are no fully fledged South African newspapers in Sesotho except for regional newsletters in Qwaqwa, Fouriesburg, Ficksburg, and possibly other Free State towns.[8]

Currently, the mainstream South African magazine Bona[11]includes Sesotho content.[8] Since the codification of Sesotho orthography, literary works have been produced in Sesotho. Notable Sesotho-language literature includes Thomas Mofolo's epic Chaka, which has been translated into several languages including English and German.[12]

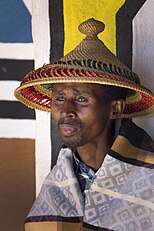

Clothing

The Basotho have a unique traditional attire. This includes the mokorotlo, a conical hat with a decorated knob at the top that is worn differently for men and women. The Basotho blanket is often worn over the shoulders or the waist and protects the wearer against the cold. Although many Sotho people wear westernized clothing, often traditional garments are worn over them.

Basotho herders

Many Basotho who live in rural areas wear clothing that suits their lifestyles. For instance, boys who herd cattle in the rural Free State and Lesotho wear the Basotho blanket and large rain boots (gumboots) as protection from the wet mountain terrain. Herd boys also often wear woolen balaclavas or caps year-round to protect their faces from cold temperatures and dusty winds.

Basotho women

Basotho women usually wear skirts and long dresses in bright colors and patterns, as well as the traditional blankets around the waist. On special occasions like wedding celebrations, they wear the Seshoeshoe, a traditional Basotho dress. The local traditional dresses are made using colored cloth and ribbon accents bordering each layer. Sotho women often purchase this material and have it designed in a style similar to West and East African dresses.

Women often wrap a long print cloth or a small blanket around their waist, either as a skirt or a second garment over it. This is commonly known as a wrap, and it can be used to carry infants on their backs.[13]

Special clothing items

Special clothing is worn for special events like initiation rites and traditional healing ceremonies.

For a Lebollo la basadi, or a girl's initiation ceremony, girls wear a beaded waist wrap called a thethana that covers the waist, particularly the crotch area and part of the buttocks. They also wear grey blankets and goatskin skirts. These garments are worn by young girls and women, particularly virgins.

For a Lebollo la banna, or a boy's initiation ceremony, boys wear a loincloth called a tshea as well as colorful blankets. These traditional outfits are often combined with more modern items like sunglasses.

Traditional Sotho healers wear the bandolier which consists of strips and strings made of leather, sinew or beads that form a cross on the chest. The bandolier often has pouches of potions attached to it for specific rituals or physical/spiritual protection. It is believed that the San people adopted this bandolier attire for healers during times when the Basotho and the San traded and developed ties through trade, marriage and friendship. The San people's use of the bandolier can be seen in their rock paintings that date to the 1700s.[14][15]

- Sotho Cultural Clothing

-

Brown shweshwe

-

Seana Marena woollen tribal blanket traditionally

-

Mokorotlo is a type of straw hat

-

Basotho women during Mokhibo

-

Blue shweshwe

Notable Sotho people

Politics

- Moshoeshoe I – Founder of the Basotho nation

- Moshoeshoe II – King of Lesotho

- Letsie III – Reigning King of the Basotho

- Queen 'Masenate Mohato Seeiso – Queen Consort of Lesotho

- Pakalitha Mosisili – Former Prime Minister of Lesotho

- Epainette Mbeki – South African anti-apartheid activist and mother of former president Thabo Mbeki of South Africa

- Tom Thabane – Former Prime Minister of Lesotho

- Ntsu Mokhehle – Former Prime Minister of Lesotho

- Leabua Jonathan – Former Prime Minister of Lesotho

- Mosiuoa Lekota – South African anti-apartheid activist, Member of Parliament. And the current President of the COPE

- Hlaudi Motsoeneng – South African radio personality and broadcasting executive

Entertainment

- Steve Kekana – South African musician

- Joshua Pulumo Mohapeloa – music composer

- Lira – South African singer

- Yvonne Chaka Chaka – South African singer

- Maleh – Lesotho-born singer

- Michael Mosoeu Moerane – choral music composer

- Mpho Koaho – Canadian-born actor of Sotho ancestry

- Terry Pheto – South African actress

- Sankomota – Lesotho jazz band

- Thebe Magugu – South African fashion designer

- Kamo Mphela – South African dancer

- Fana Mokoena – South African actor and Member of Parliament for Economic Freedom Fighters

- Tshepo "Howza" Mosese – South African actor and musician

- Kabelo Mabalane – South African musician and one third of the Kwaito group Tkzee

Sports

- Khotso Mokoena – Athlete (Long jump)

- Steve Lekoelea – Former football player for Orlando Pirates

- Aaron Mokoena – Former football player for Jomo Cosmos, Blackburn Rovers, and Portsmouth FC

- Thabo Mooki – Former football player for Kaizer Chiefs and Bafana Bafana

- Abia Nale – Former football player for Kaizer Chiefs

- Lebohang Mokoena – Football player for Moroka Swallows

- Jacob Lekgetho

- Lehlohonolo Seema – Retired footballer, Coach of Chippa United

- Kamohelo Mokotjo – Football player

- Lebohang Maboe – Football player for Mamelodi Sundowns

See also

- Sotho–Tswana peoples

- Sotho-Tswana languages

- Tswana people

- Pedi people

- Barotseland

- Lozi people

- Liphofung Historical Site

- Sekhukhuneland

- Sotho calendar

- Battle of Berea

References

- ^ "Sotho". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Posel, D. (2003) Have Migration Patterns in Post-Apartheid South Africa Changed? Conference on African Migration in Comparative Perspective. Johannesburg: 2003.

- ^ "Poverty in South Africa: Extent of access to food and income". Human Sciences Research Council Review. 4 (4). 2006. Archived from the original on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ a b South African National Census of 2011

- ^ a b Constitution of South Africa (1996)

- ^ Zerbian, S.; Barnard, E. (2008). "Phonetics of Intonation in South African Bantu Languages". Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies. 26 (2): 235–250. doi:10.2989/SALALS.2008.26.2.5.569. S2CID 1333262.

- ^ a b "Lesotho". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 11 October 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g United Nations Scientific and Educational Council (UNESCO) (2000) World Languages Survey. Paris: UNESCO.

- ^ a b c d Statistics SA (2001) Census 2001. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

- ^ a b c Lewis, P. (2009) Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Dallas: SIL International.

- ^ "Bona Magazine". Bona Magazine. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Kunene, D. (1989). Thomas Mofolo and the emergence of written Sesotho prose. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

- ^ "Traditional Basotho Dress". 5 June 2018.

- ^ Foster, Dean (15 October 2002). The Global Etiquette Guide to Africa and the Middle East: Everything You Need to Know for Business and Travel Success. John Wiley & Sons. p. 259.

- ^ Falola, Toyin; Jean-Jacques, Daniel (14 December 2015). Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. ABC-CLIO. pp. 656–657.