Marriage License

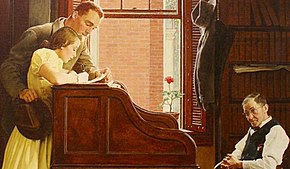

Marriage License is an oil painting by American illustrator Norman Rockwell created for the cover of the June 11, 1955, edition of The Saturday Evening Post. It depicts a young man and woman filling out a marriage license application at a government building in front of a bored-looking clerk. The man is dressed in a tan suit and has his arm around his partner, who is wearing a yellow dress and standing on tiptoe to sign her name. Although the room and its furnishings are dark, the couple are illuminated by the window beside them. The contrast between the couple and the clerk highlights two reoccurring themes in Rockwell's works: young love and ordinary life.

Rockwell had a long history of using people who lived near him as models. He used photographs of local shopkeeper Jason Braman; Stockbridge, Massachusetts, native Joan Lahart; and her fiancé Francis Mahoney as a reference while creating the painting. Lahart was suggested for the role by her sister Peggy, a nurse at the Austen Riggs Center where Mary Rockwell was receiving treatment. During the photo shoot, Braman was captured in a more natural and uninterested pose compared to the one envisioned by the artist. Rockwell liked it and used it for his painting instead.

Since its appearance in The Saturday Evening Post, the painting has been praised by critics and is considered one of Rockwell's best works. Commentators have compared it to the works of Johannes Vermeer due to Rockwell's use of light and dark. The 45.5 by 42.5 inches (116 cm × 108 cm) painting is in the collection of the Norman Rockwell Museum and has been a part of major exhibitions in 1955, 1972, and 1999. In 2004 Mad magazine published a parody of Marriage License by Richard William that used the original work to explore how same-sex marriage challenges the meaning of marriage and government role.

Description

Marriage License is an oil painting on canvas measuring 45.5 by 42.5 inches (116 cm × 108 cm).[1] It is set in a dark city hall office filled with bookshelves.[2] The floor is strewn with used cigarettes and a brass spittoon.[3][4] In the middle of the painting stand a young couple in front of a rolltop desk filling out their application for a marriage license.[4][5] The man is wearing a tan suit and has his arm protectively around his fiancée.[6] The woman wears a yellow dress with high heels but has to stand on her tiptoes to sign the document. Light from the open window beams down on the couple's faces.[5]

A bored looking older man in a bow tie and waistcoat sits behind the desk, with a cat resting beside his chair.[5] Rubber galoshes have been placed over his shoes.[7] The wearied look on the clerk's face starkly contrasts with the excited couple.[8] Behind the clerk, in the window, sits a single red geranium.[4] On top of the bookshelf is an unfolded United States flag, thought by the Norman Rockwell Museum to be a sign that the couple has come in at the very end of the day.[9] In the background a calendar gives the date as June 11, 1955, the date the painting appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post.[5]

Themes

Marriage License highlights two reoccurring themes in Norman Rockwell's works: the drab of ordinary life and the excitement of young love. The subject choice of a couple signing a marriage license, in private, rather than a public wedding was a deliberate one. Throughout his career, Rockwell consistently opted to show small moments of American life.[10] Love is a topic that Rockwell explored extensively in paintings such as The Letterman (1938), Little Girl Observing Lovers on a Train (1944), Before the Date (1949), and The University Club (1960).[11] Marriage License is one of the few times he directly addressed the theme post-World War II.[3] The subject is amplified by the juxtaposition of the excited young couple next to the uninterested clerk. Depending on the side of the desk the painting is being viewed from, the day depicted in the painting is either run-of-the-mill or monumental.[3]

Creation

Commission and models

Rockwell moved from Arlington, Vermont, to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, in 1953 to be close to his wife Mary, who was receiving psychiatric treatment at the Austen Riggs Center, and to receive therapy from Erik Erikson.[12][13] He set up a studio and continued to paint illustrations for magazine covers and yearly Boy Scout calendars.[14]

Starting in the 1930s Rockwell created his paintings from 50 to 100 reference photographs.[15] The models for these were often drawn from the local community. Marriage License's three main figures – the young couple and the older man – are drawn from around Stockbridge.[16] The office and surrounding buildings draw from both Johannes Vermeer's The Little Street and photographs of Stockbridge's town clerk's office.[17][18]

In 1954 Rockwell approached Peggy Lahart, a nurse at the Riggs center, to pose for a painting depicting a bride-to-be.[17] Peggy passed the opportunity to her younger sister Joan, who was engaged to Francis "Moe" Mahoney, a retired NBA player, in January 1955.[16] After some prodding, Mahoney agreed to pose with his fiancée. For their photo shoot, Rockwell told the couple what to wear: a specific yellow summer dress with puffed sleeves for Lahart and a "light blue shirt and wingtips" for Mahoney.[16][17] The dress had to be custom made as summerwear was impossible to buy in Stockbridge during winter.[17] The couple were each paid $25 (equivalent to $280 in 2023) and received an oil sketch of the painting as a wedding gift.[16][18][19][note 1]

The older man was modeled by Jason Braman, a shopkeeper in Stockbridge.[21] Braman was chosen as the model because his wife had recently died. Rockwell originally positioned him sitting nearer the couple.[22] During the photo shoot Braman relaxed and "slumped down" in the chair,[23] a more natural pose Rockwell took a liking to and used for the final painting.[8]

Process

Using his collection of reference photographs, Rockwell composed a series of full-size sketches which were used to create a smaller final color study.[15][note 2] A filing cabinet from the clerk's office made its way into a study but was removed in the final painting in favor of a potbelly stove to make the room look older.[17][18] The final painting was created by transferring the sketch onto the canvas and painting over it.[15] It took Rockwell just over a month to finish the painting,[25] which was framed and then sent to The Saturday Evening Post.[26] The Post had the painting color photographed. It was used to create four plates (blue, red, yellow, and black) which would be used to print a color reproduction.[26]

Provenance

Marriage License was first published as the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in 1955. That same year the painting was included in an exhibition of Rockwell's work at the Corcoran Gallery of Art organized and paid for by the magazine.[27] After the show, the work returned to Rockwell's collection until 1969 when it and thirty-four other paintings – including the Four Freedoms (1943) and Shuffleton's Barbershop (1950) – were permanently loaned to the Old Corner House in Stockbridge.[28] In 1972 the painting was included in Norman Rockwell: A Sixty Year Retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum on the condition that it was not part of the national tour of the same name.[29]

Rockwell donated the entirety of his personal collection of paintings, including Marriage License, to the Norman Rockwell Art Collection Trust in 1973.[1][30] The trust became the core of the Norman Rockwell Museum's permanent collection after the artist died in 1979. Marriage License has been displayed elsewhere only once since joining the collection, for the November 1999 – February 2002 tour, Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People, which visited the High Museum of Art, Chicago History Museum, Corcoran Gallery of Art, San Diego Museum of Art, Phoenix Art Museum, Norman Rockwell Museum, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.[31][failed verification]

Reception

The painting has been generally well received. In the catalog for the 1972 retrospective exhibition of Rockwell's works, museum director Thomas Buechner described the painting, along with Breaking Home Ties (1954), as the artist's two best works.[32] Art critic Deborah Solomon found the painting to be a "peak of [Rockwell's] talents as a realist painter",[33] and novelist John Updike praised the painting's small and "unnecessary" details.[34] Popular culture historian Christopher Finch considered Marriage License to be iconic, one of Rockwell's "most successful canvases", and belonging "with the very finest examples of Rockwell's art".[35] Writing in 1955 for The Washington Post, critic Leslie Judd Portner described the painting as boring and "pedestrian" in her scathing review of the Rockwell exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art.[36]

Philosopher of art Marcia Muelder Eaton uses Marriage License and Vermeer's The Milkmaid as foils in Art and Nonart: Reflections on an Orange Crate and a Moose Call to explore the boundaries of "aesthetic value" by testing a series of assertions about what makes "good art".[37] She tries to test the idea that only one of the two paintings draws from earlier works of art, but fails. Much like Deborah Solomon and Dave Ferman of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Eaton notes that Marriage License is influenced by Dutch old masters, based on its use of light and dark interiors.[38][39][40] When analyzing the technical skill needed to produce the works, she finds that both artists have a high degree of craftsmanship.[41] Where Eaton finds the paintings differ is on the subject matter and presentation.[42] She describes Rockwell's work as "cheaply achieved" and "childish" due to the shallow symbolism, and compares it to a mass-market cartoon.[43] Eaton later writes that she has "very little, if any, drive to hear what others have to say about it [Marriage License]" due to the lack of interpretation a viewer performs.[44]

Legacy

As a well-known Rockwell painting, Marriage License has been used as inspiration for other works. There were plans for a Christmas-themed film based on the painting and several other Rockwells in 1979.[45] The production company filmed exterior shots, but production stopped in January because Stockbridge's Board of Selectmen was not properly notified of the project.[46] Despite several attempts the producers could not receive permission to film largely because the Selectmen wanted the best possible deal for the town.[47][48]

As a response to Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, the first state supreme court decision in favor of same-sex marriage, in 2004, artist Richard Williams created a parody of Marriage License for Mad magazine titled If Norman Rockwell Depicted the 21st Century.[49] The parody stays close to the source material but with the cast iron stove replaced by a photocopier, the spittoon becoming a trash can, and a pair of gay men signing their marriage license.[50][51] The woman's yellow dress in the original is paralleled by the shirt of the man closer to the viewer.[50]

Gender studies scholar Katie Oliviero interpreted If Norman Rockwell ... as a commentary on the "competing frameworks of civil marriage's competing public and private meanings".[52] Psychologists Earl Ginter, Gargi Roysircar and Lawrence Gerstein saw it instead as a commentary on the role of government in deciding which marriages are valid and which ones are not.[53] The parody was re-posted in 2012 on Mad's website in celebration of the Second Circuit striking down the Defense of Marriage Act in United States v. Windsor.[54]

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b "Marriage License". Digital Collection. Norman Rockwell Museum. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Ferman, Dave (January 16, 2000). "Rockwell Made Ordinary Extraordinary". News-Press. Fort Myers, Florida. Knight Ridder News Service. p. 2G. Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Finch 1976, p. 81

- ^ a b c Bauer 1980, p. 56

- ^ a b c d Stump, Douglas G. (August 27, 2000). "Corcoran Exhibit Illustrates the Career of Norman Rockwell". Lebanon Daily News. Lebanon, Pennsylvania. p. 10B. Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Shaw-Eagle, Joanna (June 17, 2000). "Norman Rockwell's Fanfare for the Common Man". Washington Times. Washington, DC – via Gale OneFile: News.

- ^ Marriage License 1955, 1:22

- ^ a b Marriage License 1955, 1:03

- ^ Marriage License 1955, 1:17

- ^ Larson & Hennessey 1999, p. 48

- ^ Finch 1976, pp. 81–93

- ^ Carson, Tom (February 26, 2020). "The awakening of Norman Rockwell". Vox. Archived from the original on October 26, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ Solomon 2013, pp. 282–283

- ^ Solomon 2013, pp. 284–286

- ^ a b c Larson & Hennessey 1999, p. 57

- ^ a b c d Ryan, Bill (November 27, 1983). "Norman Rockwell's Town is Full of Familiar Faces". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Fort Worth, Texas. Hartford Courant. p. 6C. Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Meyer 1981, p. 196

- ^ a b c Marriage License 1955

- ^ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Archived from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "Marriage License (study)". Digital Collection. Norman Rockwell Museum. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Ryan, Bill (January 1, 1984). "Rockwell's real people". Saturday Evening Post. Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ^ Marriage License 1955, 0:46

- ^ Marriage License 1955, 0:50

- ^ "Marriage License (study)". Digital Collection. Norman Rockwell Museum. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- ^ Bauer 1980, p. 13

- ^ a b Larson & Hennessey 1999, p. 63

- ^ Solomon 2013, pp. 303–304

- ^ Solomon 2013, p. 418

- ^ Solomon 2013, pp. 424–428

- ^ Ceglio 2002, p. 283

- ^ Hennessey & Knutson 1999, p. 4

- ^ Buechner 1972, p. 107

- ^ Solomon 2013, p. 304

- ^ Updike 2012, pp. 22–25

- ^ Finch 2013, pp. 1, 24, and 658

- ^ Solomon 2013, p. 307

- ^ Eaton 1983, pp. 137–140

- ^ Ferman, Dave (February 20, 2000). "Rockwell Exhibit Stirs Memories". Wisconsin State Journal. Madison, Wisconsin. Fort Worth Star-Telegram. p. H1. Retrieved October 25, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Solomon 2013, pp. 304–305

- ^ Eaton 1983, p. 140

- ^ Eaton 1983, pp. 140–145, 153–154

- ^ Eaton 1983, pp. 145–149

- ^ Eaton 1983, pp. 149–151

- ^ Eaton 1983, p. 151

- ^ Knobloch, Kevin T. (January 4, 1979). "Yule TV Film To Be Shot Here". Berkshire Eagle. Pittsfield, Massachusetts. p. 23. Archived from the original on October 25, 2022. Retrieved October 25, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Knobloch, Kevin T. (January 12, 1979). "Film Producer Says Comments by Beacco have 'Hurt' Project". Berkshire Eagle. Pittsfield, Massachusetts. p. 10. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved January 23, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Film Makers Agree To Meet With Board". Berkshire Eagle. Pittsfield, Massachusetts. February 27, 1979. p. 24. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved January 23, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Moore, Steve (November 27, 1979). "Rise In Cost Of Treatment Plant Prompts Officials' Boston Trip". Berkshire Eagle. Pittsfield, Massachusetts. p. 18. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved January 23, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Oliviero 2013, pp. 167–168

- ^ a b Oliviero 2013, p. 168

- ^ Kutner, Max. "Rethinking Rockwell in the Time of Ferguson". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ^ Oliviero 2013, pp. 168–169

- ^ Ginter, Roysircar & Gerstein 2018, Chapter 13

- ^ "Norman Rockwell's "Marriage License" Reimagined as New York Strikes Down the Defense of Marriage Act". Mad Magazine. E.C. Publications. October 18, 2012. Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

Bibliography

- Bauer, Fred (1980). The Faith of America. New York: Artabras. ISBN 978-0849902802.

- Buechner, Thomas S. (1972). Norman Rockwell: A 60 Year Retrospective. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-8109204925.

- Ceglio, Clarissa J. (June 2002). "Complicating Simplicity". American Quarterly. 54 (2): 279–306. doi:10.1353/aq.2002.0011. JSTOR 30041929. S2CID 201762371.

- Eaton, Marcia Muelder (1983). Art and Nonart: Reflections on an Orange Crate and a Moose Call. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0838630846.

- Finch, Christopher (1976). Norman Rockwell's America (Reader's Digest ed.). New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810904545.

- Finch, Christopher (2013). Norman Rockwell's: 332 Magazine Covers (Kindle ed.). New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-0789204097.

- Ginter, Earl J.; Roysircar, Gargi; Gerstein, Lawrence H. (2018). Theories and Applications of Counseling and Psychotherapy: Relevance Across Cultures and Settings. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. doi:10.4135/9781506353845. ISBN 978-1412967594.

- Marriage License 1955. Norman Rockwell Museum Mobile App. Norman Rockwell Museum. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- Hennessey, Maureen Hart; Knutson, Anne, eds. (1999). Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People. Atlanta, Georgia: High Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0810963924.

- Larson, Judy L.; Hennessey, Maureen Hart. "Norman Rockwell: A New Viewpoint". In Hennessey & Knutson (1999), pp. 33–66.

- Meyer, Susan E. (1981). Norman Rockwell's People. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810917774.

- Oliviero, Katie (2013). "Yes on Proposition 8: The Conservative Opposition to Same-Sex Marriage". In Bernstein, Mary; Taylor, Verta (eds.). The Marrying Kind?: Debating Same-Sex Marriage within the Lesbian and Gay Movement. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. doi:10.5749/minnesota/9780816681716.003.0006. ISBN 978-0816681723.

- Solomon, Deborah (2013). American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell. New York: Picador. ISBN 978-0374113094.

- Updike, John (2012). Carduff, Christopher (ed.). Always Looking: Essays on Art. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0307957306.