Dzungar Khanate

Dzungar Khanate | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1634–1755 | |||||||||||||

| Status | Nomadic empire | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Ghulja[3] | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Oirat, Chagatai[4] | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Tibetan Buddhism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Khan or Khong Tayiji | |||||||||||||

• 1632-1653 | Erdeni Batur (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1671-1697 | Galdan Boshugtu Khan | ||||||||||||

• 1745-1750 | Tsewang Dorji Namjal | ||||||||||||

| Legislature |

| ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||||

• Established | 1634 | ||||||||||||

• 1619 | The first Russian record of Khara Khula | ||||||||||||

• 1676 | Galdan receives the title of Boshogtu khan from the 5th Dalai Lama | ||||||||||||

• 1688 | The Dzungar invasion of the Khalkha | ||||||||||||

• 1690 | Beginning of the Dzungar–Qing War, Battle of Ulan Butung | ||||||||||||

• 1755–1758 | Qing army occupation of Dzungaria and genocide | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1755 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1650[5] | 3,600,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• [6] | 600,000 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | pūl (a red copper coin) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Dzungar Khanate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 準噶爾汗國 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 准噶尔汗国 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||

| Tibetan | ཛེ་གུན་གར།། | ||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Зүүнгарын хаант улс | ||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠵᠡᠭᠦᠨ ᠭᠠᠷ ᠤᠨ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠨᠲᠣ ᠣᠯᠣᠰ | ||||||

| |||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||

| Uyghur | جوڭغار Jongghar | ||||||

The Dzungar Khanate, also written as the Zunghar Khanate, was an Inner Asian khanate of Oirat Mongol origin. At its greatest extent, it covered an area from southern Siberia in the north to present-day Kyrgyzstan in the south, and from the Great Wall of China in the east to present-day Kazakhstan in the west. The core of the Dzungar Khanate is today part of northern Xinjiang, also called Dzungaria.

About 1620 the western Mongols, known as the Oirats, united in Dzungaria. In 1678, Galdan received from the Dalai Lama the title of Boshogtu Khan, making the Dzungars the leading tribe within the Oirats. The Dzungar rulers used the title of Khong Tayiji, which translates into English as "crown prince".[7] Between 1680 and 1688, the Dzungars conquered the Tarim Basin, which is now southern Xinjiang, and defeated the Khalkha Mongols to the east. In 1696, Galdan was defeated by the Qing dynasty and lost Outer Mongolia. In 1717 the Dzungars conquered Tibet, but were driven out a year later by the Qing. In 1755, Qing China took advantage of a Dzungar civil war to conquer Dzungaria and destroyed the Dzungars as a people. The destruction of the Dzungars led to the Qing conquest of Mongolia, Tibet, and the creation of Xinjiang as a political administrative unit.

Etymology

"Dzungar" is a compound of the Mongolian word jegün (züün), meaning "left" or "east" and γar meaning "hand" or "wing".[8] The region of Dzungaria derives its name from this confederation. Although the Dzungars were located west of the Khalkas, the derivation of their name has been attributed to the fact that they represented the left wing of the Oirats. In the early 17th century, the head of the Oirat confederation was the leader of the Khoshut, Gushi Khan. When Gushi Khan decided to invade Tibet to replace the local Tsangpa khan in favor of rule by the Gelug, the Oirat army was organized into left and right wing. The right wing consisting of Khoshuts and Torguts remained in Tibet while the Choros and Khoid of the Left wing retreated north into the Tarim basin, since then the powerful empire of the Choros became known as the Left Wing, i.e. Zuungar.

The region was separately described in contemporary European sources as the Kingdom of the Eleuths, from an infelicitous transcription of the name "Oirats" by French missionaries.[9] This was sometimes vaguely extended to cover wide areas of Central Asia, including Afghanistan.[10]

History

Origin

The Oirats were originally from the area of Tuva during the early 13th century. Their leader, Quduqa Bäki, submitted to Genghis Khan in 1208 and his house intermarried with all four branches of the Genghisid line. During the Toluid Civil War, the Four Oirat (Choros, Torghut, Dörbet, and Khoid) sided with Ariq Böke and therefore never accepted Kublaid rule. After the Yuan dynasty's collapse, the Oirats supported the Ariq Bökid Jorightu Khan Yesüder in seizing the Northern Yuan throne. The Oirats held sway over the Northern Yuan khans until the death of Esen Taishi in 1455, after which they migrated west due to Khalkha Mongol aggression.[11] In 1486, the Oirats became embroiled in a succession dispute which gave Dayan Khan the opportunity to attack them. In the latter half of the 16th century, the Oirats lost more territory to the Tumed.[12]

In 1620, the leaders of the Choros and Torghut Oirats, Kharkhul and Mergen Temene, attacked Ubasi Khong Tayiji, the first Altan Khan of the Khalkha. They were defeated and Kharkhul lost his wife and children to the enemy. An all out war between Ubasi and the Oirats lasted until 1623 when Ubasi was killed.[13] In 1625, a conflict erupted between the Khoshut chief Chöükür and his uterine brother Baibaghas over inheritance issues. Baibaghas was killed in the fight. However, his younger brothers Güshi Khan and Köndölön Ubashi took up the fight and pursued Chöükür from the Ishim River to the Tobol River, attacking and killing his tribal followers in 1630. The infighting among the Oirats caused the Torghut chief Kho Orluk to migrate westwards until they came into conflict with the Nogai Horde, which they destroyed. The Torghuts founded the Kalmyk Khanate but still stayed in contact with the Oirats in the east. Every time a great assembly was called, they sent representatives to attend.[14]

In 1632, the Gelug Yellow Hat sect in Qinghai was being repressed by the Khalkha Choghtu Khong Tayiji, so they invited Güshi Khan to come and deal with him. In 1636, Güshi led 10,000 Oirats in an invasion of Qinghai which resulted in the defeat of a 30,000 strong enemy army and the death of Choghtu. He then entered Central Tibet, where he received from the 5th Dalai Lama the title of Bstan-'dzin Choskyi Rgyal-po (the Dharma King Who Upholds the Religion). He then claimed the title of Khan, the first non-Genghisid Mongol to do so, and summoned the Oirats to completely conquer Tibet, creating the Khoshut Khanate. Among those involved was Kharkhul's son, Erdeni Batur, who was granted the title of Khong Tayiji, married the khan's daughter Amin Dara, and sent back to establish the Dzungar Khanate on the upper Emil River south of the Tarbagatai Mountains.[15] Batur returned to Dzungaria with the title Erdeni (given by the Dalai Lama) and much booty. During his reign he made three expeditions against the Kazakhs. The conflicts by the Dzungars are remembered in a Kazakh ballad Elim-ai.[16] The Dzungars also went to war against the Kyrgyz, Tajiks, and Uzbeks when they invaded deep into Central Asia to Yasi (Turkestan) and Tashkent in 1643.[17]

Succession dispute (1653–1677)

In 1653, Sengge succeeded his father Batur, but he faced dissent from his half brothers. With the support of Ochirtu Khan of the Khoshut, this strife ended with Sengge's victory in 1661. In 1667 he captured Erinchin Lobsang Tayiji, the third and last Altan Khan. However, he himself was assassinated by his half-brothers Chechen Tayiji and Zotov in a coup in 1670.[19]

Sengge's younger brother Galdan Boshugtu Khan had been residing in Tibet at the time. Upon his birth in 1644 he was recognized as the reincarnation of a Tibetan lama who had died the previous year. In 1656 he left for Tibet, where he received education from Lobsang Chökyi Gyaltsen, 4th Panchen Lama and the 5th Dalai Lama. Upon learning of his brother's death, he immediately returned from Tibet and took revenge on Chechen. Allied with Ochirtu Sechen of the Khoshut, Galdan defeated Chechen, and drove Zotov out of Dzungaria. In 1671 The Dalai Lama bestowed the title of Khan on Galdan. Sengge's two sons Sonom Rabdan and Tsewang Rabtan revolted against Galdan but they were defeated. Although, already married Anu-Dara, granddaughter of Ochirtu, he came into conflict with his grandfather in law. Fearing Galdan's popularity, Ochirtu supported his uncle and rival Choqur Ubashi who refused to recognize Galdan's title. The victory over Ochirtu in 1677 resulted Galdan's domination of the Oirats. In the next year the Dalai Lama gave the highest title of Boshoghtu (or Boshughtu) Khan to him,[20]

Conquest of the Yarkent Khanate (1678–1680)

From the late 16th century onward, the Yarkent Khanate fell under the influence of the Khojas. The Khojas were Naqshbandi Sufis who claimed descent from the prophet Muhammad or from the Rashidun caliphs. By the reign of Sultan Said Khan in the early 16th century, the Khojas already had a strong influence in court and over the khan. In 1533, an especially influential Khoja named Makhdum-i Azam arrived in Kashgar, where he settled and had two sons. These two sons hated each other and they passed down their mutual hatred down to their children. The two lineages came to dominate large parts of the khanate, splitting it between two factions: the Aq Taghliq (White Mountain) in Kashgar and the Qara Taghliq (Black Mountain) in Yarkand. Yulbars patronized the Aq Taghliqs and suppressed the Qara Taghliqs, which caused much resentment, and resulted in his assassination in 1670. He was succeeded by his son who ruled from only a brief period before Ismail Khan was enthroned. Ismail reversed the power struggle between the two Muslim factions and drove out the Aq Taghliq leader, Afaq Khoja. Afaq fled to Tibet, where the 5th Dalai Lama aided him in enlisting the help of Galdan Boshugtu Khan.[22]

In 1680, Galdan led 120,000 Dzungars into the Yarkent Khanate. They were aided by the Aq Taghliqs and Hami and Turpan, which had already submitted to the Dzungars. Ismail's son Babak Sultan died in the resistance against in the battle for Kashgar. The general Iwaz Beg died in the defense of Yarkand. The Dzungars defeated the Moghul forces without much difficulty and took Ismail and his family prisoner. Galdan installed Abd ar-Rashid Khan II, son of Babak, as puppet khan.[23]

First Kazakh war (1681–1685)

In 1681, Galdan invaded the north of Tengeri Mountain and attacked the Kazakh Khanate but failed to take Sayram.[25] In 1683 Galdan's armies under Tsewang Rabtan took Tashkent and Sayram. They reached the Syr Darya and crushed two Kazakh armies. After that Galdan subjugated the Black Kyrgyz and ravaged the Fergana Valley.[26] His general Rabtan took Taraz city. From 1685 Galdan's forces aggressively pushed westward, forcing the Kazakhs ever further west.[27] The Dzungars established dominion over the Baraba Tatars and extracted yasaq (tribute) from them. Converting to Orthodox Christianity and becoming Russian subjects was a tactic by the Baraba to find an excuse not to pay yasaq to the Dzungars.[28]

Khalkha war (1687–1688)

The Oirats had established peace with the Khalkha Mongols since Ligdan Khan died in 1634 and the Khalkhas were preoccupied with the rise of the Qing dynasty. However, when the Jasaghtu Khan Shira lost part of his subjects to the Tüsheet Khan Chikhundorj, Galdan moved his orda near the Altai Mountains to prepare an attack. Chikhundorj attacked the right wing of the Khalkhas and killed Shira in 1687. In 1688, Galdan dispatched troops under his younger brother Dorji-jav against Chikhundorj but they were eventually defeated. Dorji-jav was killed in battle. Chikhundorj then murdered Degdeehei Mergen Ahai of the Jasaghtu Khan who was on the way to Galdan. To avenge the death of his brother, Galdan established friendly relations with the Russians who were already at war with Chikhundorj over territories near Lake Baikal. Armed with Russian firearms, Galdan led 30,000 Dzungar troops into Khalkha Mongolia in 1688 and defeated Chikhundorj in three days. The Siberian Cossacks, meanwhile, attacked and defeated a Khalkha army of 10,000 near Lake Baikal. After two bloody battles with the Dzungars near Erdene Zuu Monastery and Tomor, Chakhundorji and his brother Jebtsundamba Khutuktu Zanabazar fled across the Gobi Desert to the Qing dynasty and submitted to the Kangxi Emperor.[29]

First Qing war (1690–1696)

Late in the summer of 1690, Galdan crossed the Kherlen River with a force of 20,000 and engaged a Qing army at Battle of Ulan Butung 350 kilometers north of Beijing near the western headwaters of the Liao River. Galdan was forced to retreat and escaped total destruction because the Qing army did not have the supplies or ability to pursue him. In 1696, the Kangxi Emperor led 100,000 troops into Mongolia. Galdan fled from the Kherlen only to be caught by another Qing army attacking from the west. He was defeated in the ensuing Battle of Jao Modo near the upper Tuul River. Galdan's wife, Anu, was killed and the Qing army captured 20,000 cattle and 40,000 sheep. Galdan fled with a small handful of followers. In 1697 he died in the Altai Mountains near Khovd on 4 April. Back in Dzungaria, his nephew Tsewang Rabtan, who had revolted in 1689, was already in control as of 1691.[29]

Chagatai rebellion (1693–1705)

Galdan installed Abd ar-Rashid Khan II, son of Babak, as puppet khan in the Yarkent Khanate. The new khan forced Afaq Khoja to flee again, but Abd ar-Rashid's reign was also ended unceremoniously two years later when riots erupted in Yarkand. He was replaced by his brother Muhammad Imin Khan. Muhammad sought help from the Qing dynasty, Khanate of Bukhara, and the Mughal Empire in combating the Dzungars. In 1693, Muhammad conducted a successful attack on the Dzungar Khanate, taking 30,000 captives. Unfortunately Afaq Khoja appeared again and overthrew Muhammad in a revolt led by his followers. Afaq's son Yahiya Khoja was enthroned but his reign was cut short in 1695 when both he and his father were killed while suppressing local rebellions. In 1696, Akbash Khan was placed on the throne, but the begs of Kashgar refused to recognize him, and instead allied with the Kyrgyz to attack Yarkand, taking Akbash prisoner. The begs of Yarkand went to the Dzungars, who sent troops and ousted the Kyrgyz in 1705. The Dzungars installed a non-Chagatayid ruler Mirza Alim Shah Beg, thereby ending the rule of Chagatai khans forever. Abdullah Tarkhan Beg of Hami also rebelled in 1696 and defected to the Qing dynasty. In 1698, Qing troops were stationed in Hami.[30]

Second Kazakh war (1698)

In 1698 Galdan's successor Tsewang Rabtan reached Tengiz lake and Turkestan, and the Dzungars controlled Zhei-Su and Tashkent until 1745.[31] The Dzungars' war on the Kazakhs pushed them into seeking aid from Russia.[32]

Second Qing war (1718–1720)

Tsewang Rabtan's brother Tseren Dondup invaded the Khoshut Khanate in 1717, deposed Yeshe Gyatso, killed Lha-bzang Khan, and looted Lhasa. The Kangxi Emperor retaliated in 1718, but his military expedition was annihilated by the Dzungars in the Battle of the Salween River, not far from Lhasa.[33] A second and larger expedition sent by Kangxi expelled the Dzungars from Tibet in 1720. They brought Kälzang Gyatso with them from Kumbum to Lhasa and installed him as the 7th Dalai Lama in 1721.[34] The people of Turpan and Pichan took advantage of the situation to rebel under a local chief, Amin Khoja, and defected to the Qing dynasty.[35]

Galdan Tseren (1727–1745)

Tsewang Rabtan died suddenly in 1727 and was succeeded by his son Galdan Tseren. Galdan Tseren drove out his half-brother Lobszangshunu. He continued the war against the Kazakhs and the Kalkha Mongols. In retaliation against attacks against his Khalkha subjects, the Yongzheng Emperor of the Qing dynasty sent an invasion force of 10,000, which the Dzungars defeated near the Khoton Lake. The next year however, the Dzungars suffered a defeat against the Khalkhas near Erdene Zuu Monastery. In 1731, the Dzungars attacked Turpan, which had previously defected to the Qing dynasty. Amin Khoja led the people of Turpan in a retreat into Gansu where they settled in Guazhou. In 1739, Galdan Tseren agreed to the boundary between Khalkha and Dzungar territory.[36]

Collapse (1745–1756)

Galdan Tseren died in 1745, triggering widespread rebellion in the Tarim Basin, and starting a succession dispute among his sons. In 1749 Galden Tseren's son Lama Dorji seized the throne from his younger brother, Tsewang Dorji Namjal. He was overthrown by his cousin Dawachi and the Khoid noble Amursana, but they too fought over control of the khanate.

As a result of their dispute, in 1753, three of Dawachi's relatives ruling the Dörbet and Bayad defected to the Qing and migrated into Khalkha territory. The next year, Amursana also defected. In 1754, Yusuf, the ruler of Kashgar, rebelled and forcefully converted the Dzungars living there to Islam. His older brother, Jahan Khoja of Yarkand, also rebelled but was captured by the Dzungars due to the treachery of Ayyub Khoja of Aksu. Jahan's son Sadiq gathered 7,000 men in Khotan and attacked Aksu in retaliation.

In the spring of 1755, the Qianlong Emperor sent an army of 50,000 against Dawachi. He presented his invasion as benevolent, and aimed at ending the sufferings of the Dzungars, while ascribing their misery to themselves:[37]

"Alas, you Dzungars, you are of the same ilk as the Mongols, aren’t you? Why did you separate from them? (...) People stood there with their mouths open because of the misery. I was anxious that your misery came to a standstill. And I hope that it will not — with my help — last till the next morning (...) If Heaven wants to strengthen somebody, people cannot injure him even if they want his downfall. ...You want to honour the Yellow Doctrine and pray to Buddha and the Bodhisattvas. But in your hearts you are like man-eating Rakshas. Therefore you were unable to escape from your self incurred retribution with your lives when your crimes were at the lowest [moral level] and your wickedness reached a zenith"

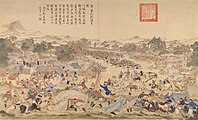

Storming of the Camp at Gädän-Ola (1755)

The Qing army met almost no resistance and destroyed the Dzungar Khanate within the span of 100 days.[39] The Chinese army, supplemented on the way by Muslim and renegade Dzungar troops, surprised Dawachi at the site of Borotola in June 1755, about 300 li from Ili.[40] Dawachi had about 10,000 troops, and retreated to Mount Keteng, about 80 li from Ili, while sending messengers for reinforcements, but the messengers were intercepted by the Chinese. The Qing army was able to surprise and capture Dawachi's army at the camp, and a charge was led by the Dzungar renegade Ayusi and 20 of his men, who stormed the camp and where able to conduct about 8,000 prisonners to the Chinese camp (an event depicted in the Qing painting "Storming of the Camp at Gädän-Ola").[40] Only 2,000 soldiers escaped with Dawachi at their head.[40] Dawachi fled into the mountains north of Aksu but was captured by the Uyghur leader Khojis, beg of Uchturpan, at the request of the Chinese, and delivered to the Qing.[41]

Surrender of Dawachi (1755)

Dawachi surrendered to the Qing general Zhaohui.[41] The scene was immortalized in the painting "Zhaohui receives the surrender of Dawachi at Ili" by the Jesuit court painter Ignatius Sichelbart. Dawachi was taken to Beijing, but was pardonned by the Emperor. Together with his captor Khojis, he was made a Prince, and "awarded banner privileges".[40]

Amursana's rebellion (1755–1757)

After defeating the Dzungar Khanate, the Qing planned to install khans for each of the four Oirat tribes, but Amursana, who had been an ally of the Qing against Dawachi, wanted to rule over all the Oirats. Instead the Qianlong Emperor made him only khan of the Khoid.

In the summer, Amursana along with Mongol leader Chingünjav led a revolt against the Qing. Amursana was defeated in the Battle of Oroi-Jalatu (1756), in which Chinese general Zhao Hui attacked the Dzungars at night in present Wusu, Xinjiang. Unable to defeat the Qing, Amursana fled north to seek refuge with the Russians and died of smallpox in Russian lands in September 1757. In the spring of 1762 his frozen body was brought to Kyakhta for the Manchu to see. The Russians then buried it, refusing the Manchu request that it be handed over for posthumous punishment.[43][44][45]

Later encounters took place with the remaining Dzungar forces, in the Battle of Khorgos, in which the partisans of Amursana were defeated in 1758 by Prince Cäbdan-jab. Again in 1758, at the Battle of Khurungui, General Zhao Hui ambushed and defeated the Dzungarian forces on Mount Khurungui, near Almaty, Kazakhstan.[46]

-

The Battle of Oroi-Jalatu, 1756. Chinese general Zhao Hui attacked the Dzungars at night in present Wusu, Xinjiang. Painting by Giuseppe Castiglione.

-

"The Victory of Khorgos". The partisans of Amursana were defeated in 1758 by Prince Cäbdan-jab. Painting by Jean Denis Attiret.[47]

-

Battle of Khurungui, 1758. General Zhao Hui ambushes and defeats the Zungarian forces of Amoursana on Mount Khurungui (near Almaty, Kazakhstan). Painted by Jean-Damascène Sallusti.

Aftermath

Paintings and propaganda

The Qianlong Emperor took great care to document his successes in the war.[9] He ordered the painting of the 100 most meritorious servitors of the Qing (紫光阁功臣像: brave Qing officers, generals, and also a few Torghut and Dörbed allies, as well as vanquished Choros Oirats, or Muslim Uyghur allies such as Khojis or Amin Khoja), as well as paintings of the battle scenes whenever the Qing were successful. The faces are in Western realistic style, while the bodies were probably drawn by Chinese court artists.[9] According to contemporary Jesuit painter Jean-Denis Attiret: "During the whole duration of this war against the Eleuths and other Tartars, their allies, whenever the imperials troops gained some victories, the painters were ordered to paint them. Those of the most important officers who had played the decisive roles in the events were favoured to appear in the paintings according to what really had happened".[9] These paintings were all made by foreign artists, specifically the Jesuits under Giuseppe Castiglione, and Chinese court-painters under their direction.[9]

-

The Choros-Oirat leader Dawachi in Qing costume, after the Dzungar-Qing War. Painting by Jean Denis Attiret.

-

The Choros-Oirat Dawa (达瓦) in Qing costume, after the Dzungar-Qing War. Painting by Jean Denis Attiret.

-

The Dörbed-Oirat Tseren (车凌) in Qing dynasty costume. Painting by Jean Denis Attiret.

-

The Dörbed-Oirat Buyan Tegus in Qing dynasty costume. Painting by Jean Denis Attiret.

-

The Oirat renegade Ayusi in his Qing uniform. Painting by Giuseppe Castiglione.

Muslim Uyghur "White Mountaineers" rebellions (1757–1759)

When Amursana rebelled against the Qing dynasty, the Aq Taghliq (i.e. 'White Mountaineers', also known as Āfāqīs) Khojas Burhanuddin and Jahan rebelled in Yarkand. Their rule was not popular and the people greatly disliked them for appropriating anything they needed from clothing to livestock. In February 1758, The Qing sent Yaerhashan and Zhao Hui with 10,000 troops against the Aq Taghliq regime. Zhao Hui was besieged by enemy forces at Yarkand until January 1759, but otherwise the Qing army did not encounter any difficulties on campaign. The khoja brothers fled to Badakhshan where they were captured by the ruler Sultan Shah, who executed them and handed Jahan's head to the Qing. The Tarim Basin was pacified in 1759.[48]

Muslim Uyghur revolts against the Qing would still last for approximately one hundred years, the Āfāqī Khojas waging numerous military campaigns as a part of a holy war in an effort to retake Altishahr from the Qing.

Genocide

According to the Qing scholar Wei Yuan (1794–1857), the Dzungar population before the Qing conquest was around 600,000 in 200,000 households. Wei Yuan wrote that about 40 percent of the Dzungar households were killed by smallpox, 20 percent fled to Russia or Kazakh tribes, and 30 percent were killed by Manchu bannermen. For several thousands of li, there were no gers except of those who had surrendered.[49][50][51] Wen-Djang Chu wrote that 80 percent of the 600,000 or more Dzungars were destroyed by disease and attack[52] which Michael Clarke described as "the complete destruction of not only the Dzungar state but of the Dzungars as a people".[53]

It's argued by the historian Peter Perdue that the destruction of the Dzungars was the result of an explicit policy of extermination launched by the Qianlong Emperor which lasted for two years.[50] His commanders were reluctant to carry out his orders, which he repeated several times using the term jiao (extermination) over and over again. The commanders Hadaha and Agui were punished for only occupying Dzungar lands but letting the people escape. The generals Jaohui and Shuhede were punished for not showing sufficient zeal in exterminating rebels. Qianlong explicitly ordered the Khalkha Mongols to "take the young and strong and massacre them".[54] The elderly, children, and women were spared but they could not preserve their former names or titles.[54] Mark Levene, a historian whose recent research interests focus on genocide, states that the extermination of the Dzungars was "arguably the eighteenth century genocide par excellence".[55]

Widespread anti-Dzungar opinion by former Dzungar subjects contributed to their genocide. The Muslim Kazakhs and former people of the Yarkent Khanate in the Tarim Basin (now called Uyghurs), were treated poorly under by the Buddhist Dzungars, who used them as slave labor, and participated in the Qing invasion and attacked the Dzungars. Uyghur leaders like Khoja Emin or Khojis were granted titles within the Qing nobility,[56][57][58] and acted as an intermediary with Muslims from the Tarim Basin. They told the Muslims that the Qing only wanted to kill Oirats and that they would leave the Muslims alone. They also convinced the Muslims to aid the Qing in killing Oirates.[59]

Demographic change in Xinjiang

After the destruction of the Dzungar Oirat people, the Qing dynasty sponsored the settlement of millions of Han, Hui, Xibe, Daur, Solon, Turkic Oasis people (Uyghurs) and Manchus in Dzungaria since the land had been emptied.[61] Stanley W. Toops notes that modern Xinjiang's demographic situation still reflects the settlement initiative of the Qing dynasty. One third of Xinjiang's total population consisted of Han, Hui, and Kazakhs in the north while around two-thirds were Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang's Tarim Basin.[62][63][64] Some cities in northern Xinjiang such as Ürümqi and Yining were essentially made by the Qing settlement policy.[65]

The elimination of the Buddhist Dzungars led to the rise of Islam and its Muslim Begs as the predominant moral political authority in Xinjiang. Many Muslim Taranchis also moved to northern Xinjiang. According to Henry Schwarz, "the Qing victory was, in a certain sense, a victory for Islam".[66] Ironically, the destruction of the Dzungars by the Qing led to the consolidation of Turkic Muslim power in the region, since Turkic Muslim culture and identity was tolerated or even promoted by the Qing.[67]

In 1759, the Qing dynasty proclaimed that the land formerly belonging to the Dzungars was now part of "China" (Dulimbai Gurun) in a Manchu memorial.[68][69][70] The Qing ideology of unification portrayed the "outer" non-Han Chinese like the Mongols, Oirats, and Tibetans together with the "inner" Han Chinese as "one family" united in the Qing state. The Qing described the phrase "Zhong Wai Yi Jia" (中外一家) or "Nei Wai Yi Jia" (內外一家, "interior and exterior as one family"), to convey this idea of "unification" to different peoples.[71]

Leaders of the Dzungar Khanate

- Khara Khula, title: Khong Tayiji

- Erdeni Batur, title: Khong Tayiji

- Sengge, title: Khong Tayiji

- Galdan Boshugtu Khan, titles: Khong Tayiji, Boshogtu Khan

- Tsewang Rabtan, title: Khong Tayiji, Khan

- Galdan Tseren, title: Khong Tayiji

- Tsewang Dorji Namjal, title: Khong Tayiji

- Lama Dorji, title: Khong Tayiji

- Dawachi, title: Khong Tayiji

- Amursana‡

‡ Note: Although Amursana had de facto control of some areas of Dzungaria during 1755–1756, he could never officially become Khan due to the inferior rank of his clan, the Khoid.

Culture

The Oirats converted to Tibetan Buddhism in 1615.[14]

Oirat society was similar to other nomadic societies. It was heavily dependent on animal husbandry but also practiced limited agriculture. After the conquest of the Yarkent Khanate in 1680, they used people from the Tarim Basin(taranchi) as slave labour to cultivate land in Dzungaria. The Dzungar economy and industry was fairly complex for a nomadic society. They had iron, copper, and silver mines producing raw ore, which the Dzungars made into weapons and shields, including even firearms, bullets, and other utensils. The Dzungars were able to indigenously manufacture firearms to a degree that was unique in Central Asia at the time.[72] In 1762, the Qing army discovered four large Dzungar bronze cannons, eight "soaring" cannons, and 10,000 shells.[73]

In 1640, the Oirats created an Oirat Mongol Legal Code which regulated the tribes and gave support to the Gelug Yellow Hat sect. Erdeni Batur assisted Zaya Pandita in creating the Clear Script.[74]

Gallery

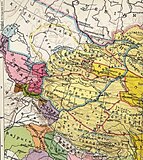

-

The Dzungar Khanate in 1750

-

This map fragment shows territories of Oirats as in 1706 (Map Collection of the Library of Congress: "Carte de Tartarie" of Guillaume de L'Isle (1675–1726)).

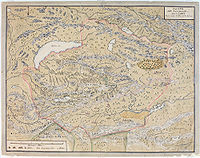

-

The Dzungar and Kalmyk states (a fragment of the map of Russian Empire of Peter the Great, that was created by a Swedish soldier in c. 1725)

-

A map of the Dzungar Khanate, by a Swedish officer in captivity there in 1716–33, which include the region known today as Zhetysu

See also

| History of the Mongols |

|---|

|

| History of Mongolia |

|---|

|

| History of Xinjiang |

|---|

|

| History of Tibet |

|---|

|

| See also |

|

|

References

Citations

- ^ "Зүүнгарын хаант улс". Монголын түүх.

- ^ MA, Soloshcheva. "The "Conquest Of Qinghai" Stele Of 1725 And The Aftermath Of Lobsang Danjin's Rebellion In 1723-1724" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ James A. Millward, Ruth W. Dunnell, Mark C. Elliott New Qing imperial history, p.99

- ^ Predecessor of Modern Uyghur

- ^ Bang, Peter Fibiger; Bayly, C. A.; Scheidel, Walter (2 December 2020). The Oxford World History of Empire: Volume One: The Imperial Experience. Oxford University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-19-977311-4.

- ^ Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia, by James B. Minahan, p. 210.

- ^ C. P. Atwood Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.622

- ^ For the Mongols the primary direction was south. Gaunt, John (2004). Modern Mongolian: A Course-Book. London: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-7007-1326-4. Mongolian maps placed the south at the top, so west was to the right and east was to the left. Akira, Kamimura. "A Preliminary Analysis of Old Mongolian Manuscript Maps: Towards an Understanding of the Mongols' Perception of the Landscape" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e Walravens, Hartmut; Hartmut, Walravens (15 June 2017). "Symbolism of sovereignty in the context of the Dzungar campaigns of the Qianlong emperor". Written Monuments of the Orient. 3 (1): 73–90. doi:10.17816/wmo35126. ISSN 2410-0145.

- ^ "Plate LXXXIX. Asia.", Encyclopaedia Britannica, vol. II (1st ed.), Edinburgh: Colin Macfarquhar, 1771.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 142.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 153.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 144.

- ^ a b Adle 2003, p. 145.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 146.

- ^ Genina, Anna (2015). Claiming Ancestral Homelandsː Mongolian Kazakh migration in Inner Asia (PDF) (A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan). p. 113.

- ^ Ahmad Hasan Dani; Vadim Mikhaĭlovich Masson; UNESCO (1 January 2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast: from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. pp. 116–. ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1.

- ^ 伊犂等處台吉

- ^ Autobiography of Dalai Lama V, Vol. Kha, fol 107b. II 5–6

- ^ Martha Avery The Tea Road: China and Russia meet across the Steppe, p. 104

- ^ 伊犂等處宰桑

- ^ Grousset 1970, p. 501.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 193.

- ^ 伊犂等處民人

- ^ Baabar, Christopher Kaplonski, D. Suhjargalmaa Twentieth-century Mongolia, p. 80

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 147.

- ^ Michael Khodarkovsky Where Two Worlds Met: The Russian State and the Kalmyk Nomads, 1600–1771, p. 211

- ^ Frank, Allen J. (1 April 2000). "Varieties of Islamization in Inner Asia The case of the Baraba Tatars, 1740–1917". Cahiers du monde russe. Éditions de l’EHESS: 252–254. doi:10.4000/monderusse.46. ISBN 2-7132-1361-4. ISSN 1777-5388.

- ^ a b Adle 2003, p. 148.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 193-199.

- ^ C. P. Atwood ibid, p. 622.

- ^ Ariel Cohen (1998). Russian Imperialism: Development and Crisis. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-0-275-96481-8.

- ^ Richardson, Hugh E. (1984). Tibet and its History. Second Edition, Revised and Updated, pp. 48–9. Shambhala. Boston & London. ISBN 0-87773-376-7 (pbk)

- ^ Richardson, Hugh E. (1984). Tibet and its History. Second Edition, Revised and Updated, pp. 48–9. Shambhala. Boston & London. ISBN 0-87773-376-7 (pbk)

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 200.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 149.

- ^ a b Walravens, Hartmut; Hartmut, Walravens (15 June 2017). "Symbolism of sovereignty in the context of the Dzungar campaigns of the Qianlong emperor". Written Monuments of the Orient. 3 (1): 82. doi:10.17816/wmo35126. ISSN 2410-0145.

- ^ Dennys, Nicholas Belfield; Eitel, Ernest John; Barlow, William C.; Ball, James Dyer (1888). The China Review, Or, Notes and Queries on the Far East. "China Mail" Office. p. 115.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d Dennys 1888, p. 115.

- ^ a b Adle 2003, p. 201.

- ^ Chu, Petra ten-Doesschate; Ding, Ning (1 October 2015). Qing Encounters: Artistic Exchanges between China and the West. Getty Publications. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-60606-457-3.

- ^ C. P. Atwood ibid, 623

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 95.

- ^ G. Patrick March, Eastern Destiny: Russian in Asia and the Pacific, 1996, Chapter 12

- ^ Pirazzoli-T'Serstevens, Michèle (1 January 1969). Gravures des conquêtes de l'empereur de Chine K'Ien-Long au musée Guimet (in French). (Réunion des musées nationaux - Grand Palais) réédition numérique FeniXX. p. 10. ISBN 978-2-7118-7570-2.

- ^ Chu, Petra ten-Doesschate; Ding, Ning (1 October 2015). Qing Encounters: Artistic Exchanges between China and the West. Getty Publications. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-60606-457-3.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 203.

- ^ Lattimore, Owen (1950). Pivot of Asia; Sinkiang and the inner Asian frontiers of China and Russia. Little, Brown. p. 126.

- ^ a b Perdue 2005, p. 283-287

- ^ ed. Starr 2004, p. 54.

- ^ Chu, Wen-Djang (1966). The Moslem Rebellion in Northwest China 1862–1878. Mouton & co. p. 1.

- ^ "Michael Edmund Clarke, In the Eye of Power (doctoral thesis), Brisbane 2004, p37" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ a b Perdue 2005, p. 283.

- ^ Levene, Mark (2008). "Chapter 8: Empires, Native Peoples, and Genocide". In Moses, A. Dirk (ed.). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Berghahn Books. p. 188. ISBN 978-1845454524.

- ^ Kim 2008, p. 308

- ^ Kim 2008, p. 134

- ^ Kim 2008, p. 49

- ^ Kim 2008, p. 139.

- ^ "北京保利国际拍卖有限公司". www.polypm.com.cn.

- ^ Perdue 2009, p. 285.

- ^ ed. Starr 2004, p. 243.

- ^ Toops, Stanley (May 2004). "Demographics and Development in Xinjiang after 1949" (PDF). East-West Center Washington Working Papers (1). East–West Center: 1. Archived from the original on 16 July 2007.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Tyler 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Millward 1998, p. 102.

- ^ Liu & Faure 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Liu & Faure 1996, p. 76.

- ^ Dunnell 2004, p. 77.

- ^ Dunnell 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Elliott 2001, p. 503.

- ^ Dunnell 2004, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Haines, Spencer (2017). "The 'Military Revolution' Arrives on the Central Eurasian Steppe: The Unique Case of the Zunghar (1676 - 1745)". Mongolica: An International Journal of Mongolian Studies. 51: 170–185.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 165.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 155.

General and cited sources

- Adle, Chahryar (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia 5.

- Dennys, Nicholas Belfield (1888). The China Review, Or, Notes and Queries on the Far East. "China Mail" Office. p. 115.

- Dunnell, Ruth W.; Elliott, Mark C.; Foret, Philippe; Millward, James A (2004). New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. Routledge. ISBN 1134362226. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804746842. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Haines, R Spencer (2015). "Myth, Misconception, and Motive for the Zunghar Intervention in Khalkha Mongolia in the 17th Century". Paper Presented at the Third Open Conference on Mongolian Studies, Canberra, ACT, Australia. The Australian National University.

- Haines, R Spencer (2016). "The Physical Remains of the Zunghar Legacy in Central Eurasia: Some Notes from the Field". Paper Presented at the Social and Environmental Changes on the Mongolian Plateau Workshop, Canberra, ACT, Australia. The Australian National University.

- Haines, Spencer (2017). "The 'Military Revolution' Arrives on the Central Eurasian Steppe: The Unique Case of the Zunghar (1676 - 1745)". Mongolica: An International Journal of Mongolian Studies. 51. International Association of Mongolists: 170–185.

- Kim, Kwangmin (2008). Saintly Brokers: Uyghur Muslims, Trade, and the Making of Qing Central Asia, 1696–1814. University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 978-1109101263. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Liu, Tao Tao; Faure, David (1996). Unity and Diversity: Local Cultures and Identities in China. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9622094023. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231139243. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Perdue, Peter C (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674042025. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Perdue, Peter C (2005). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 067401684X. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Grousset, Rene (1970), The Empire of the Steppes

- Starr, S. Frederick, ed. (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765613182. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Theobald, Ulrich (2013). War Finance and Logistics in Late Imperial China: A Study of the Second Jinchuan Campaign (1771–1776). BRILL. ISBN 978-9004255678. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Tyler, Christian (2004). Wild West China: The Taming of Xinjiang (illustrated, reprint ed.). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813535336. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Zhao, Gang (January 2006). "Reinventing China Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century" (PDF). Modern China. 32 (1). Sage Publications: 3–30. doi:10.1177/0097700405282349. JSTOR 20062627. S2CID 144587815. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- Хойт С.К. Последние данные по локализации и численности ойрат Archived 14 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine // Проблемы этногенеза и этнической культуры тюрко-монгольских народов. Вып. 2. Элиста: Изд-во КГУ, 2008. стр. 136–157.

- Хойт С.К. Этническая история ойратских групп. Элиста, 2015. 199 с.

- Хойт С.К. Данные фольклора для изучения путей этногенеза ойратских групп // Международная научная конференция «Сетевое востоковедение: образование, наука, культура», 7–10 декабря 2017 г.: материалы. Элиста: Изд-во Калм. ун-та, 2017. с. 286–289.

External links

Media related to Dzungar Khanate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dzungar Khanate at Wikimedia Commons

!["The Victory of Khorgos". The partisans of Amursana were defeated in 1758 by Prince Cäbdan-jab. Painting by Jean Denis Attiret.[47]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/04/The_Victory_of_Khorgos1.jpg/197px-The_Victory_of_Khorgos1.jpg)