Syrmia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2015) |

Syrmia (Ekavian Serbo-Croatian: Srem/Срем or Ijekavian Srijem/Сријем) is a region of the southern Pannonian Plain, which lies between the Danube and Sava rivers. It is divided between Serbia and Croatia. Most of the region is flat, with the exception of the low Fruška gora mountain stretching along the Danube in its northern part.

Etymology

The word "Syrmia" is derived from the ancient city of Sirmium (now Sremska Mitrovica).[1][2] Sirmium was a Celtic or Illyrian town founded in the third century BC.

Srem (Serbian Cyrillic: Срем) and Srijem are used to designate the region in Serbia and Croatia respectively.[3] Other names for the region include:

- Latin: Syrmia or Sirmium

- Hungarian: Szerémség, Szerém, or Szerémország

- German: Syrmien

- Slovak: Sriem

- Rusyn: Срим

- Romanian: Sirmia

History

Prehistory

Between 3000 BC and 2400 BC, Syrmia was at the centre of Indo-European Vučedol culture.[4]

Roman era

Sirmium was conquered by Romans in the first century BC and became the economic and political capital of Pannonia.[5] In 6 AD, there was an uprising of the indigenous peoples against Roman rule. However, ten later Roman Emperors were born in Sirmium or nearby. They included Herennius Etruscus (227-251), Hostilian (230?-251), Decius Traian (249-251), Claudius II (268-270), Quintillus (270), Aurelian (270-275), Probus (276-282), Maximianus Herculius (285-310), Constantius II (337-361) and Gratian (367-383).[citation needed]

Early Middle Ages

In the 6th century, Syrmia was part of the Byzantine province of Pannonia. During that time, Byzantine rule was challenged by Ostrogoths and Gepids. In 567, Byzantine rule was fully restored, although it later collapsed during the Siege of Sirmium by Avars and Slavs (582). It remained under Avar rule up to c. 800, when it came under the control of the Frankish Empire. In 827, Bulgars invaded Syrmia and continued to rule after a peace treaty in 845 AD. The region was later incorporated into the Principality of Lower Pannonia, but during the 10th century it became a battleground between Hungarians, Bulgarians, and Serbs.[6]

At the beginning of the 11th century, the ruler of Syrmia was Duke Sermon, vassal of the Bulgarian emperor Samuil. There had been Bulgar resistance to Byzantine rule. This collapsed and Sermon, who refused to capitulate was captured and killed by Constantine Diogenes. A new but ultimately short lived area of governance named the Thema of Sirmium was established. It included the region of Syrmia and what is now Mačva. In 1071, Hungarians took over the region of Syrmia, but the Byzantine Empire reconquered the province after the victory over the Hungarians in the Battle of Syrmia (1167). Byzantine rule ended in 1180, when Syrmia was taken again by the Hungarians.

Late Middle Ages

In the 13th century, the region was controlled by the Kingdom of Hungary. On 3 March 1229, the acquisition of Syrmia was confirmed by Papal bull. Pope Gregory IX wrote, "[Margaretha] soror…regis Ungarie [acquired] terram…ulterior Sirmia".[7] In 1231, The Duke of Syrmia was Giletus. In the 1200s, the territory around Syrmia was divided into two counties: Syrmia in the east and Valkó (Vukovar) in the west.

In the 13th century, between 1282 and 1316, Syrmia was ruled by Stefan Dragutin of Serbia.[8][9][unreliable source?] Initially, Dragutin was a vassal of Hungary but later ruled independently. Dragutin died in 1316, and was succeeded by his son, Stefan Vladislav II (1316–1325). In 1324, Vladislav II was defeated by Stefan Uroš III Dečanski of Rascia. Lower Syrmia became the subject of dispute between the Kingdoms of Rascia and Hungary.

In 1404, Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor ceded part of Syrmia to Stefan Lazarević of Serbia.[10]

From 1459, the Hungarian kings endorsed the House of Branković and later, the Berislavići Grabarski family as the titular heads of the Serbian Despotate of which Syrmia was a part. They resided in Kupinik (modern Kupinovo). The local rulers included Vuk Grgurević (1471 to 1485); Đorđe Branković (1486 to 1496), Jovan Branković (1496 to 1502), Ivaniš Berislavić (1504 to 1514), and Stjepan Berislavić (1520 to 1535). In 1522, the last of the titular Serbian despots in Syrmia, Stjepan Berislavić, moved to Slavonia, ahead of invading Ottoman forces. Another important local governor was Laurence of Ilok, Duke of Syrmia (1477 to 1524), who reigned over large parts of the region from Ilok.

Early modern period

In 1521, parts of Syrmia fell to the Ottomans and by 1538, the entire region was under Ottoman control. Between 1527 and 1530, Radoslav Čelnik ruled Syrmia as an Ottoman vassal. The area of Ottoman administration in Syrmia was known as the Sanjak of Syrmia.

In 1699, the Habsburg monarchy took western Syrmia from the Ottomans as part of the Treaty of Karlowitz.[11] Until the Treaty of Passarowitz at the end of the Austro-Turkish War of 1716-18, remainder of Syrmia was part of the Habsburg Military Frontier.[12]

At the end of the Austro-Russian-Turkish War of 1735–1739, there was a migration of Albanians from the Kelmendi tribe to Syrmia, who were recorded as speaking Albanian as late as 1921.[13]

In 1745, the County of Syrmia was established as part of the Habsburgs' Kingdom of Slavonia.[14] During the Austro-Turkish War (1788-1791), there were émigrés from Serbia who settled in Syrmia.[15]

-

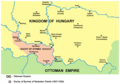

Szerém and Valkó counties, 1370

-

Duchy of Syrmia of Radoslav Čelnik, 1527 to 1530

-

Sanjak of Syrmia, 1568 to 1571

-

Habsburg-Ottoman frontier in Syrmia, 1699

19th century

In 1807, the Tican's Rebellion, a Syrmian peasant uprising, occurred on Ruma estate and in the village of Voganj in Ilok estate.

In 1848, most of Syrmia was part of the temporary Serbian Voivodship, a Serb autonomous region within the Austrian Empire. By a 1849 decree of the Emperor Franz Joseph, the Voivodship of Serbia and Tamiš Banat was created, comprising Northern Syrmia, including Ilok and Ruma.[16][17]

After 1860, the County of Syrmia was re-established and returned to the Kingdom of Slavonia. In 1868, the Kingdom of Slavonia became part of Croatia-Slavonia in the Kingdom of Hungary.

20th century

On 29 October 1918, Syrmia became a part of the newly independent State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. On 24 November 1918, the Assembly of Syrmia proclaimed the unification of Serb-populated parts of Syrmia with the Kingdom of Serbia. However, from 1 December 1918, all of Syrmia was made a part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

From 1918 to 1922, Syrmia remained within the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and from 1922 to 1929, Syrmia was a province (oblast). In 1929, after a new territorial division, Syrmia was divided between Danube Banovina and Drina Banovina, in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and in 1931, it was divided between Danube Banovina and Sava Banovina. In 1939, the western part of Syrmia was included into the newly formed Banovina of Croatia.

In 1941, Syrmia was occupied by the World War II Axis powers and its entire territory was ceded to the Independent State of Croatia, a Nazi puppet state. The fascist Ustashe regime systematically murdered Serbs (as part of the Genocide of the Serbs), Jews (The Holocaust), Roma (The Porajmos), and some political dissidents. In August 1942, following the joint military anti-partisan operation in the Syrmia by the Ustashe and German Wehrmacht, it turned into a massacre by the Ustasha militia that left up to 7,000 Serbs dead.[18] Among those killed was the prominent painter Sava Šumanović, who was arrested along with 150 residents of Šid.[19] In 1945, with the creation of new borders, eastern Syrmia became part of the People's Republic of Serbia, while western Syrmia became part of the People's Republic of Croatia.

In 1991, Croatia declared its independence from SFR Yugoslavia, and the Croatian War of Independence ensued shortly thereafter. The Serbs self-proclaimed in one part western Syrmia an autonomous region called the "Serbian Autonomous Region of Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia". This region was one of the two Serbian autonomous regions that formed the self-declared and unrecognized Republic of Serbian Krajina. The region was ethnically cleansed of its Croat and some other non-Serb population leading to some of the most serious violation of human rights including the Lovas killings, the Tovarnik massacre, the Vukovar massacre and other crimes. The autonomous regions lasted until 1995, when it was reintegrated in Croatia. After the war, a number of towns and municipalities in the Croatian part of Syrmia were designated Areas of Special State Concern.

-

Serbian Voivodship, 1848

-

The County of Syrmia within Croatia-Slavonia, 1881

-

Liberated partisan territory, late 1942

-

Memorial Complex to the Syrmian Front

Demographics

In 2002, the population of Syrmia in Serbia was 790,697.[20] 668,745 (84.58%) were Serb. In 2001, the population of the Croatian Vukovar-Srijem county was 204,768.[21] The census showed, that Croats made up 78.3% of total population, Serbs 15.5%, Hungarians 1%, Rusyns 0.9% and others.

Geography

The majority of Syrmia is located in the Srem district of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina in Serbia. A smaller area around Novi Sad is part of the South Bačka district, and another smaller area around Novi Beograd, Zemun, and Surčin belongs to the City of Belgrade. The remaining part of Syrmia is part of the Vukovar-Syrmia County in Croatia.

Borders

The present international border of the region of Syrmia was drawn in 1945 by the Đilas commission. It divided the Yugoslav constituent republic of Croatia and the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, itself part of Serbia, within Yugoslavia.

Milovan Đilas, a Montenegrin and then a confidant of Josip Broz Tito, drew the border according to demographic criteria, which explains why the town of Ilok on the Danube, with a Croat majority, lies east of Šid in Serbia, with a Serb majority. The border drawn in 1945 was very similar to the 1931-1939 border between the Danube Banovina and the Sava Banovina within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Bordering regions

- Bačka to the north

- Banat to the east

- Šumadija the south-east

- Mačva to the south

- Semberija to the south-west

- Slavonia to the west. The border between Syrmia and Slavonia is unclear. It runs approximately along a line through Vukovar, Vinkovci, and Županja or it follows the Bosut, Barica and Vuka rivers.

Cities

List of cities in Syrmia (with population):

- Serbia

- Belgrade city region

- Novi Beograd (217,180)

- Zemun (146,172)

- Batajnica (48,600)

- Surčin (14,209)

- Dobanovci (8,114)

- Vojvodina

- Sremska Mitrovica (39,041)

- Ruma (32,125)

- Inđija (26,244)

- Stara Pazova (18,628)

- Šid (16,301)

- Petrovaradin (13,917)

- Sremska Kamenica (11,140)

- Sremski Karlovci (8,839)

- Beočin (8,037)

- Irig (4,854)

- Belgrade city region

- Croatia

Petrovaradin, Sremska Kamenica, Sremski Karlovci and Beočin are geographically located in Syrmia, but they are part of South Bačka District.

Municipalities

Municipalities in Serbian Syrmia:

The Syrmian villages of Neštin and Vizić are part of the municipality of Bačka Palanka, the main part of which is in Bačka. Several settlements that are part of the municipality of Sremska Mitrovica are located in Syrmia in Mačva.

Municipalities and villages in Croatian Syrmia:

Mountains

Syrmia's principal mountain is Fruška Gora. Its highest peak is Crveni Čot at 539 m.

See also

References

- ^ Stewart Traill, Thomas (1860). The Encyclopaedia Britannica: Or, Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature, Volume 20. Little, Brown, & Company. p. 327.

- ^ Protić, Marijana; Smičiklas, Nemanja; Bulajić, Vladimir (2017). "Conservation, Restoration, and Presentation of Two Mosaics from Room 16, Imperial Palace, Sirmium". In Teutonico, Jeanne Marie; Friedman, Leslie; Abed, Aïcha Ben (eds.). The Conservation and Presentation of Mosaics: At What Cost?: Proceedings of the 12th Conference of the International Committee for the Conservation of Mosaics, Sardinia, October 27–31, 2014. Getty Publications. p. 387. ISBN 9781606065334.

- ^ Gecser, Ottó; Laszlovszky, József; Nagy, Balázs; Sebők, Marcell; Szende, Katalin, eds. (2010). Promoting the Saints: Cults and Their Contexts from Late Antiquity until the Early Modern Period. Central European University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9789633863923.

- ^ Syrmia, vjesnik.hr; accessed 13 April 2015.

- ^ Mennen, Inge (2011). Power and Status in the Roman Empire, AD 193-284. BRILL. p. 40. ISBN 9789004203594.

- ^ Ćirković 2004.

- ^ "Margit of Hungary" FMG Accessed 13 April 2015.

- ^ Veselinović R. Istorija Srpske pravoslavne crkve sa narodnom istorijom I Belgrade, 1969. p. 18

- ^ Grujić R. Pravoslavna Srpska crkva, Kragujevac, 1989, p22.

- ^ Stepanović, Predrag (1986). A Taxonomic Description of the Dialects of Serbs and Croats in Hungary: The Štokavian Dialect. Akad. K. p. 22. ISBN 9783412074845.

- ^ Stoye J. Marsigli's Europe, 1680-1730 Yale University Press, 1994 p185 ISBN 0300055420, 9780300055429 Accessed at Google Books 3 August 2016.

- ^ Ingrao, Samardžić & Pešalj 2011, p. 193.

- ^ Karl Gottlieb von Windisch: On the Kelmendi in Syrmia

- ^ "Establishment and Organisation of Counties in Eastern Croatia from 1745-1848". Glasnik arhiva Slavonije i Baranje. 6: 34. 2001.

The empress Maria Theresa renewed in 1745 three Slavonian counties: the Virovitica county with the centre in Osijek, the Požega county with the centre in Požega and the Syrmia county with the centre in Vukovar.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 160.

- ^ Petsinis, Vassilis (2019). National Identity in Serbia: The Vojvodina and a Multi-Ethnic Community in the Balkans. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 9781788317085.

- ^ Ivanišević, Alojz (1984). Kroatische Politik der Wiener Zentralstellen von 1849 bis 1852 (in German). VWGÖ. p. 48. ISBN 9783853695784.

..die Einverleibung der seit dem 18.11.1849 zur [Serbisch] Vojvodschaft gehörenden syrmischen Bezirke Ruma und Ilok

- ^ Korb, Alexander (2010c). "Integrated Warfare? The Germans and the Ustaša Massacres: Syrmia 1942". In Shepherd, Ben (ed.). War in a Twilight World: Partisan and Anti-Partisan Warfare in Eastern Europe, 1939–1945. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-29048-8.

- ^ Greif, Gideon (2018). Jasenovac - Auschwitz of the Balkans. Knjiga komerc. p. 437. ISBN 9789655727272.

- ^ Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova 2002. Knjiga 1: Nacionalna ili etnička pripadnost po naseljima. Srbija, Republički zavod za statistiku Beograd 2003; ISBN 86-84433-51-3

- ^ Census Archived 2006-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895-1526. London & New York: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781850439776.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (2005). When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472025600.

- Коматина, Ивана; Коматина, Предраг (2018). "Византијски и угарски Срем од X до XIII века" [The Byzantine and Hungarian Syrmia in the 10th-13th Centuries]. Зборник радова Византолошког института (in Serbian). 55: 141–164.

- Komatina, Predrag (2010). "The Slavs of the mid-Danube basin and the Bulgarian expansion in the first half of the 9th century" (PDF). Зборник радова Византолошког института. 47: 55–82.

- Petar Milošević (1981). Srem u prošlosti. Novinsko-izdavačka radna organizacija "Sremske novine.".

- Žarko Atanacković (1968). Srem u narodnooslobodilačkom ratu i socijalističkoj revoluciji. Šimanovci, Mesna zajednica-Mesni odbor SUB NOR-a.

- Đorđe Cvejić; Jovan Babović; Miodrag Živković (1982). Srem u samoupravnoj socijalističkoj Jugoslaviji 1945-1981. NIO Poslovna politika.

- Slavko Gavrilović (1979). Srem od kraja XVII do sredine XVIII veka. Filozofski fakultet u Novom Sadu, Institut za istoriju.

- Mihailo Dinić. Sredjnevekovni Srem.

- Миодраг Матицки (2007). Срем кроз векове: слојеви култура Фрушке горе и Срема : зборник радова. Вукова Задужбина. ISBN 978-86-902961-5-6.

- Слободан Ћурчић (2012). Атлас насеља Војводине: Срем. Матица српска. ISBN 978-86-7946-108-7.

- Pálosfalvi, Tamás (2018). From Nicopolis to Mohács: A History of Ottoman-Hungarian Warfare, 1389-1526. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 9789004375659.

- Pešalj, Jovan (2010). "Early 18th-Century Peacekeeping: How Habsburgs and Ottomans Resolved Several Border Disputes after Karlowitz". Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699–1829. Berlin: LIT Verlag. pp. 29–42. ISBN 9783643106117.

- Radojević, Mira (1992). "Sporazum Cvetković-Maček i pitanje razgraničenja u Sremu" (PDF). Istorija 20. Veka: Časopis Instituta za savremenu istoriju. 10 (1–2): 61–72.

- Radojević, Mira (1996). "Srpsko-hrvatski spor oko Vojvodine 1918-1941" (PDF). Istorija 20. Veka: Časopis Instituta za savremenu istoriju. 14 (2): 39–73.

45°10′12″N 19°17′17″E / 45.170°N 19.288°E