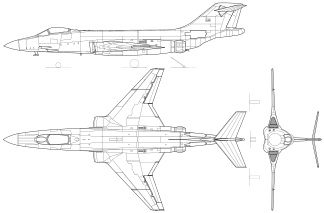

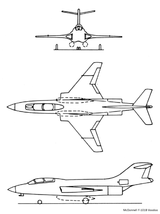

McDonnell F-101 Voodoo

| F-101 Voodoo | |

|---|---|

| |

| McDonnell F-101B Voodoo | |

| Role | Fighter aircraft |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell Aircraft Corporation |

| First flight | 29 September 1954 |

| Introduction | May 1957 |

| Retired | 1972 (USAF) 1973 (ROCAF) 1982 (US ANG) 1984 (Canada) |

| Primary users | United States Air Force (historical) Republic of China Air Force (historical) Royal Canadian Air Force (historical) |

| Number built | 807 |

| Developed from | McDonnell XF-88 Voodoo |

| Variants | McDonnell CF-101 Voodoo |

The McDonnell F-101 Voodoo is a supersonic jet fighter designed and produced by the American McDonnell Aircraft Corporation.

Development of the F-101 commenced during the late 1940s as a long-range bomber escort (then known as a penetration fighter) for the United States Air Force's (USAF) Strategic Air Command (SAC). It was also adapted as a nuclear-armed fighter-bomber for the USAF's Tactical Air Command (TAC), and as a photo reconnaissance aircraft based on the same airframe. On 29 September 1954, it performed its maiden flight. The F-101A set a number of world speed records for jet-powered aircraft, including fastest airspeed, attaining 1,207.6 miles (1,943.4 km) per hour on 12 December 1957.[1]

Delays in the 1954 interceptor project led to demands for an interim interceptor aircraft design, a role that was eventually won by the F-101B Voodoo. This role required extensive modifications to add a large radar to the nose of the aircraft, a second crew member to operate it, and a new weapons bay using a rotating door that held its four AIM-4 Falcon missiles or two AIR-2 Genie rockets hidden within the airframe until it was time to be fired. The F-101B entered service with USAF Air Defense Command in 1959 and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in 1961. While the Voodoo was a moderate success, it may have been more important as an evolutionary step towards its replacement in most roles, the F-4 Phantom II, one of the most successful Western fighter designs of the 1950s; the Phantom would retain the twin engines, twin crew for interception duties, and a tail mounted well above and behind the jet exhaust but was an evolution of the F3H Demon while the Voodoo was developed from the earlier XF-88 Voodoo.

The Voodoo's career as a fighter-bomber was relatively brief, but the reconnaissance versions served for some time. Along with the US Air Force's Lockheed U-2 and US Navy's Vought RF-8 Crusaders, the RF-101 reconnaissance variant of the Voodoo was instrumental during the Cuban Missile Crisis and saw extensive service during the Vietnam War.[2] Interceptor versions served with the Air National Guard until 1982, and in Canadian service, they were a front line part of NORAD until their replacement with the CF-18 Hornet in the 1980s. The type was operated in the reconnaissance role until 1979. US examples were handed off to the USAF Air National Guard where they were operated until 1982. The RCAF Voodoos were in service until 1984.

Design and development

Background and XF-88

Initial design on what would eventually become the Voodoo began in June 1946 in response to a USAAF Penetration Fighter Competition launched just after World War II.[3] This competition called for a long-range, high-performance fighter to escort a new generation of bombers, similar to the wartime role of the North American P-51 Mustang in escorting the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated B-24 Liberators across contested airspace. McDonnell was amongst several companies to respond to the competition; their design benefitted from recently captured German research into high speed jet aircraft.[4][5]

On 14 February 1947, McDonnell was awarded a contract (AC-14582) to produce a pair of prototypes, designated XF-88 Voodoo.[6][7] The first prototype (serial number 46-6525), which was powered by two 3,000 lbf (13.3 kN) Westinghouse XJ34-WE-13 turbojets, flew from Muroc on 20 October 1948.[8][9] Preliminary testing revealed that while handling and range was adequate, the top speed was a disappointing 641 mph (1,032 km/h) at sea level.[10] After fitting McDonnell-designed afterburners to the second prototype, thrust was increased to 3,600 lbf (16.1 kN) with corresponding performance increases in top speed, initial rate of climb and reduced takeoff distance. Fuel consumption was greatly increased by use of the afterburners, however, reducing the range.[8][11]

Although the XF-88 won the "fly-off" competition against the competing Lockheed XF-90 and North American YF-93, the detonation of the first nuclear weapon by the Soviet Union resulted in the United States Air Force (USAF) (created in 1947) re-evaluating its fighter needs, with interceptors being more important and bomber escorts being of reduced priority, and it terminated the Penetration Fighter program in 1950.[12][13] Another factor in the termination was budgetary limitations.[9][7] Analysis of Korean War missions, however, revealed that contemporary USAF strategic bombers were vulnerable to fighter interception. In early 1951, the USAF issued a new requirement for a bomber escort, to which all major US manufacturers submitted designs.[14] The McDonnell design was a larger and higher-powered version of the XF-88 and won the bid during May 1951. To reflect the level of changes involved, the redesigned F-88 was designated F-101 Voodoo in November 1951.[15][16]

Enlarged design

The new design was considerably larger, carrying three times the initial fuel load and designed around larger, more powerful Pratt & Whitney J57 turbojets.[17] The greater dimensions of the J57 engines required modifications to the engine bays, and modification to the intakes to allow a larger amount of airflow to the engine. The new intakes were also designed to be more efficient at higher Mach numbers. In order to increase aerodynamic efficiency, reduce structural weight and alleviate pitch-up phenomena recently identified in-flight testing of the Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket, an aircraft with a control surface configuration similar to the XF-88, the horizontal tail was relocated to the top of the vertical stabilizer, giving the F-101 its signature "T-tail". In late 1952, the mission of the F-101 was changed from "penetration fighter" to "strategic fighter", which entailed equal emphasis on both the bomber escort mission and on nuclear weapons delivery. The new Voodoo mock-up with the reconfigured inlets, tail surfaces, landing gear, and dummy nuclear weapon was inspected by Air Force officials in March 1953.[18] The design was approved, leading to an initial production order for 29 F-101As being placed on 28 May 1953. No prototypes were required as the F-101 was considered to be a straightforward development of the XF-88,[19] with the Cook-Cragie production policy, in which initial low-rate production would be used for testing without the use of separate prototypes, chosen instead.[20][21]

Changing roles and into production

Despite securing an order for the type, McDonnell received a stop order for production on 16 April 1954; this was due to a substantial cutback in funding for the USAF in general. Meaningful production activity was not resumed until a favourable instruction was received by the company on 2 November 1954.[22] At this point, the USAF gave McDonnell an operational deadline of early 1937.[23]

The first production aircraft, F-101A serial number 53-2418, performed its maiden flight on 29 September 1954 from Edwards AFB; during this fight, it attained a maximum speed of Mach 0.9 (960 km/h) at an altitude of 35,000 feet (11,000 m).[24] This aircraft, which is privately owned, has been moved to the Evergreen Maintenance Center in Marana, Arizona, restored, and now on display at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum in McMinnville, Oregon.[25] It was previously on display at the Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum.

The end of the conflict in Korea and the development of the jet-powered Boeing B-52 Stratofortress negated the need for fighter escort and the Strategic Air Command opted to withdraw from the program. Despite SAC's loss of interest, the F-101A had attracted the attention of Tactical Air Command (TAC), leading to the F-101 being reconfigured as a fighter bomber.[26][27] In this capacity, it was intended to carry a single nuclear weapon for use against tactical targets such as airfields. TAC requested numerous alterations to the F-101 to suit the new role, including additional apparatus to permit air-to-ground communication, provisions to carry external pods, and structural strengthening.[28][29]

Through the support of TAC, testing of the F-101 was resumed, with Category II flight tests beginning in early 1955. A number of problems were identified and were mostly resolved during this phase of development. Issues were found with the autopilot, hydraulics, viewfinder, and control system; McDonnell typically replaced unsatisfactory parts with redesigned counterparts.[30] One particular issue was the aircraft's dangerous tendency towards severe pitch-up when flown at a high angle of attack; this would never be entirely rectified.[31][32] However, the USAF was satisfied with the installation of an active inhibitor system to deter such instances.[33] Around 2,300 improvements were made to the F-101 between 1955 and 1956 ahead of full-rate production commencing in November 1956.[34]

Operational history

F-101A / RF-101G

On 2 May 1957, the first F-101A was delivered to the 27th Strategic Fighter Wing, which transferred to TAC in July that year,[20][35] replacing their F-84F Thunderstreak. The F-101A was powered by two Pratt & Whitney J57-P-13 turbojets,[19] allowing good acceleration, a high rate of climb, ease in penetrating the sound barrier in level flight, and a maximum performance of Mach 1.52. The F-101's large internal fuel capacity allowed a range of approximately 3,000 mi (4,828 km) nonstop.[36] The aircraft was fitted with an MA-7 fire-control radar for both air-to-air and air-to-ground use, augmented by a Low Altitude Bombing System (LABS) for delivering nuclear weapons,[19] and was designed to carry a Mk 28 nuclear bomb. The original intended payload for the F-101A was the McDonnell Model 96 store, a large fuel/weapons pod similar in concept to that of the Convair B-58 Hustler, but was cancelled in March 1956 before the F-101 entered service. Other operational nuclear payloads included the Mk 7, Mk 43, and Mk 57 weapons. While theoretically capable of carrying conventional bombs, rockets, or Falcon air-to-air missiles,[37] the Voodoo never used such weapons operationally.[38] It was fitted with four 20mm M39 cannon, with one cannon often removed in service to make room for a TACAN beacon-receiver.

The F-101 set a number of speed records, including: a JF-101A (the ninth F-101A modified as a testbed for the more powerful J-57-P-53 engines of the F-101B) setting a world speed record of 1,207.6 mph (1,943.4 km/h) on 12 December 1957 during "Operation Firewall",[39] beating the previous record of 1,132 mph (1,811 km/h) set by the Fairey Delta 2 in March the previous year. The record was then subsequently taken in May 1958 by a Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. On 27 November 1957, during "Operation Sun Run," an RF-101C set the Los Angeles-New York City-Los Angeles record in six hours and 46 minutes, the New York to Los Angeles record in three hours and 36 minutes, and the Los Angeles to New York record in three hours and seven minutes.[40]

A total of 77 F-101As were built, only 50 of which were ever used operationally while the remainder were used exclusively for experimental work.[35][41] They were gradually withdrawn from USAF service starting in 1966.[42] Twenty-nine survivors were converted to RF-101G specifications with a modified nose, housing reconnaissance cameras in place of cannons and radar. These served with the Air National Guard through 1972.[43][44]

RF-101A

In October 1953, the USAF requested that two F-101As be built as prototype YRF-101A tactical reconnaissance aircraft.[45] These were followed by 35 RF-101A production aircraft.[46] The RF-101A shared the airframe of the F-101A, including its 6.33 g (62 m/s²) limit, but replaced the radar and cannons with up to six cameras in the reshaped nose.[47][48] Various electronics were incorporated at the request of TAC.[49] Like all other models of the F-101, it had provision for both flying boom and probe-and-drogue in-flight refueling capability, as well as for a buddy tank that allowed it to refuel other aircraft.[37][50] It entered service in May 1957,[51][30] replacing the RB-57 Canberra.

On 6 May 1957, the RF101A entered service, the first unit to operate the type being 363d Tactical Reconnaissance Wing, stationed at Shaw AFB, South Carolina.[52] During October 1962, RF-101As from the 363d Tactical Reconnaissance Wing performed reconnaissance sorties over Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis.[2] Allegedly, the aircraft's performance over Cuba highlighted its shortcomings as a reconnaissance aircraft, motivating a series of modifications to improve its performance.[53] All USAF RD-101As were phased out of service during 1971.[54]

During October 1959, eight RF-101As were transferred to Taiwan, which used them for overflights of the Chinese mainland.[55][56] These ROCAF RF-101A were modified with the RF-101C vertical fins and air intake; this intake is used to cool the drag chute compartment and eliminates the five minute limit on using the afterburners on the RF-101A.[57] Two were reportedly shot down.[citation needed]

F-101B / CF-101B / EF-101B

In the late 1940s, the USAF had started a research project into future interceptor aircraft that eventually settled on an advanced specification known as the 1954 interceptor. Contracts for this specification eventually resulted in the selection of the Convair F-102 Delta Dagger, but by 1952 it was becoming clear that few parts of the specification other than the airframe would be ready by 1954; the engines, weapons, and fire control systems were all going to take too long to get into service. Thus, an effort was started to quickly produce an interim supersonic design to replace the various subsonic interceptors then in service, and the F-101 airframe was selected as a starting point.[58]

Although McDonnell proposed the designation F-109 for the new aircraft (which was to be a substantial departure from the basic Voodoo),[59] the USAF assigned the designation F-101B.[60] It was first deployed into service on 5 January 1959, with the 60th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron.[61] Production of this model ended in March 1961.[62] The Voodoo featured a modified cockpit to carry a crew of two, with a larger and more rounded forward fuselage to hold the Hughes MG-13 fire control radar of the F-102. It had a data link to the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) system, allowing ground controllers to steer the aircraft towards its targets by making adjustments through the plane's autopilot. The F-101B had more powerful Pratt & Whitney J57-P-55 engines, making it the only Voodoo not using the −13 engines. The new engines featured a substantially longer afterburner than J57-P-13s. To avoid a major redesign, the extended afterburners were simply allowed to extend out of the fuselage by almost 8 ft (2.4 m). The more powerful engines and aerodynamic refinements allowed an increased speed of Mach 1.85.[37]

The F-101B was stripped of the four M39 cannons and carried four AIM-4 Falcon air-to-air missiles instead, arranged two apiece on a rotating pallet in the fuselage weapons bay.[37] The initial load was two GAR-1 (AIM-4A) semi-active radar homing and two GAR-2 (AIM-4B) infrared-guided weapons with one of each carried on each side of the rotating pallet.[63] After the first two missiles were fired, the door turned over to expose the second pair. Standard practice was to fire the weapons in SARH/IR pairs to increase the likelihood of a hit. Late-production models had provision for two 1.7-kiloton MB-1/AIR-2 Genie nuclear rockets on one side of the pallet with IR-guided GAR-2A (AIM-4C) on the other side. "Project Kitty Car" upgraded most earlier F-101Bs to this standard beginning in 1961.[38][64]

Between 1963 and 1966, F-101Bs were upgraded under the Interceptor Improvement Program (IIP; also known as "Project Bold Journey"), being outfitted with a fire control system enhancement against hostile ECM and an infrared sighting and tracking (IRST) system in the nose in place of the in-flight refueling probe.[65]

The F-101B was produced in greater numbers than the F-101A and F-101C, with a total of 479 being delivered by the end of production in 1961.[66][62] Most of these were delivered to the Air Defense Command (ADC) beginning in January 1959.[61] The only foreign customer for the F-101B was Canada, where it was locally referred to as the CF-101 Voodoo.[67]

The F-101B was withdrawn from ADC service between 1968 and 1971, with many surviving USAF aircraft transferred to the Air National Guard (replacing F-102s), serving until 1982.[68] The last Voodoo in US service (F-101B-105-MC, AF Ser. No. 58-300) was finally retired by the 2nd Fighter Weapons Squadron at Tyndall AFB, Florida on 21 September 1982.[69]

F-101C / RF-101H

The F-101A fighter-bomber had been accepted into Tactical Air Command (TAC) service despite a number of problems. Among others, its airframe had proven to be capable of withstanding only 6.33 g (62 m/s²) maneuvers, rather than the intended 7.33 g (72 m/s²).[33][28] An improved model, the F-101C, was introduced in 1957. It had a 500 lb (227 kg) heavier structure to allow 7.33-g maneuvers as well as a revised fuel system to increase the maximum flight time in afterburner.[70] Like the F-101A, it was also fitted with an underfuselage pylon for carrying nuclear weapons, as well as two hardpoints for 450-US-gallon (1,700 L) drop tanks.[37] A total of 47 F101Cs were produced.[70][44]

Originally serving with the 27th Tactical Fighter Wing at Bergstrom AFB, Texas, the aircraft was transferred in 1958 from TAC to the 81st Tactical Fighter Wing, part of United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) which operated three squadrons from the twin RAF air stations Bentwaters & Woodbridge.[71] The 78th Tactical Fighter Squadron was stationed at Woodbridge, while the 91st and 92nd were stationed at Bentwaters. The 81st TFW served as a strategic nuclear deterrent force, the Voodoo's long-range putting almost all of the Warsaw Pact countries, and targets up to 500 miles (800 km) deep into the Soviet Union within reach.

Both the A and C model aircraft were assigned to the 81st TFW and were used interchangeably within the three squadrons. Operational F-101A/C were upgraded in service with Low Angle Drogued Delivery (LADD) and Low Altitude Bombing System (LABS) equipment for its primary mission of delivering nuclear weapons at extremely low altitudes. Pilots were trained for high speed, low-level missions into Soviet or Eastern Bloc territory, with primary targets being airfields. These missions were expected to be one-way, with the pilots having to eject behind Soviet lines.[70]

The F-101C never saw combat and was replaced in 1966 with the F-4C Phantom II.[20] Thirty-two aircraft were later converted for unarmed reconnaissance use with the RF-101H designation. They served with Air National Guard units until 1972.[20][72]

RF-101C

Using the reinforced airframe of the F-101C, the RF-101C first flew on 12 July 1957,[20] entering service in 1958. Like the RF-101A, the RF-101C had up to six cameras in place of radar and cannons in the reshaped nose and retained the bombing ability of the fighter-bomber versions.[73] As it was intended to be flown unarmed, various passive defensive systems were incorporated, including the AN/APS-54 radar warning receiver.[74] It lacked a true all-weather capability due to the USAF choosing to eliminate the AN/APN-82 electronic navigation system planned for it.[75] 166 RF-101Cs were built, including 96 originally scheduled to be F-101C fighter-bombers.[47]

On 27 November 1957, during Operation Sun Run, an RF-101C piloted by then-Captain Robert Sweet set the Los Angeles-New York City-Los Angeles record in six hours and 46 minutes, and New York to Los Angeles record in three hours and 36 minutes. Another RF-101C, piloted by then-Lieutenant Gustav Klatt, set a Los Angeles to New York record of three hours and seven minutes.[40]

The RF-101C saw service during the Cuban Missile Crisis and soon followed the North American F-100 Super Sabres in October 1961, into combat when RF-101s from the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing deployed to south east Asia, performing reconnaissance flights over Laos and Vietnam.[76] Operations in this theatre quickly exposed the need for nighttime reconnaissance, for which the aircraft was not originally equipped to perform.[77] The 1964 Project "Toy Tiger" fitted some RF-101C with a new camera package and a centerline pod for photo-flash cartridges. Some were further upgraded under the Mod 1181 program with automatic control for the cameras. Some officials remained dissatisfied with the RF-101C's nighttime photographic capability.[78][79]

The RF-101C acted as pathfinders for F-100 bombers during early strikes in the theatre.[80] The RF-101C sustained losses during the conflict, the first loss to enemy ground fire was recorded in November 1964, although close calls occurred as early as 14 August 1962; North Vietnamese air defenses became increasingly effective over time.[81][82] From 1965 through November 1970, its role was gradually taken over by the RF-4C Phantom II. In some 35,000 sorties, 39 aircraft were lost, 33 in combat,[83][84] including five to SAMs, one to an airfield attack, and one in air combat to a MiG-21 in September 1967. The RF-101C's speed made it largely immune to MiG interception. 27 of the combat losses occurred on reconnaissance missions over North Vietnam. In April 1967, ALQ-71 ECM pods were fitted to provide some protection against SAMs. Although the Voodoo could again operate at medium altitudes, the added drag and weight decreased the RF-101's speed enough to be vulnerable to the maneuverable (and cannon-equipped) MiGs and thus require fighter escort.

After its withdrawal from Vietnam, the RF-101C continued to serve with USAF units through 1979. In service, the RF-101C was nicknamed the "Long Bird"; it was the only version of the Voodoo to see combat.[85]

TF-101B / F-101F / CF-101F

Some of the F-101Bs were completed as dual-control operational trainer aircraft initially dubbed TF-101B, but later redesignated F-101F. Seventy-nine new-build F-101Fs were manufactured, and 152 more existing aircraft were later modified with dual controls. Ten of these were supplied to Canada under the designation CF-101F. These were later replaced with 10 updated aircraft in 1971.

RF-101B

In the early 1970s, a batch of 22 former RCAF CF-101Bs was delivered to the USAF and converted into RF-101B reconnaissance aircraft, each aircraft had its radar and weapons bay replaced with a set of three KS-87B cameras and two AXQ-2 TV cameras. An in-flight refueling boom receptacle was also installed. These aircraft served with the 192d Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron of the Nevada Air National Guard through 1975. They proved to be relatively expensive to operate and maintain and had a short service life.

Variants

- F-101A

- initial production fighter bomber, 77 produced[86]

- NF-101A

- one F-101A used by General Electric for testing of the General Electric J79 engine[86]

- YRF-101A

- two F-101As built as prototype reconnaissance models[86]

- RF-101A

- first reconnaissance version, 35 built[86]

- F-101B

- two-seat interceptor, the most numerous version with 479 built (including CF-101B)[86]

- CF-101B

- 112 F-101Bs transferred to Royal Canadian Air Force[86]

- RF-101B

- 22 former RCAF CF-101Bs modified for reconnaissance use[86]

- TF-101B

- dual-control trainer version of F-101B, redesignated F-101F, 79 built[86]

- EF-101B

- single F-101B converted for use as a radar target and leased to Canada[86]

- NF-101B

- F-101B prototype based on the F-101A airframe; the second prototype was built with a different nose[86]

- F-101C

- improved fighter-bomber, 47 built[86]

- RF-101C

- reconnaissance version of F-101C airframe, 166 built[86]

- F-101D

- proposed version with General Electric J79 engines, not built[86]

- F-101E

- another J79 proposal, not built[86]

- F-101F

- dual-control trainer version of F-101B; 79 re-designated TF-101Bs plus 152 converted F-101Bs[86]

- CF-101F

- Canadian designation for 20 TF-101B/F-101F dual-control aircraft[86]

- TF-101F

- 24 dual-control versions of F-101B, re-designated F-101F (these are included in the -F total)[86]

- RF-101G

- 29 F-101As converted for ANG reconnaissance[86]

- RF-101H

- 32 F-101Cs converted for reconnaissance use[86]

Operators

Canada

Canada

- Royal Canadian Air Force (1961-1968)

- Canadian Armed Forces

- Air Defence Command (1968-1975)

- Air Command (1975-1984 (historical)

Taiwan

Taiwan

United States

United States

Aircraft on display

Following the type's retirement, a large number of F-101s are preserved in museums or on display as gate guards.

Specifications (F-101B)

Data from The Complete Book of Fighters,[88] Encyclopedia of US Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems[89]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 67 ft 5 in (20.55 m)

- Wingspan: 39 ft 8 in (12.09 m)

- Height: 18 ft 0 in (5.49 m)

- Wing area: 368 sq ft (34.2 m2)

- Airfoil: root: NACA 65A007 (modified); tip: NACA 65A006 (modified)[90]

- Empty weight: 28,495 lb (12,925 kg)

- Gross weight: 45,665 lb (20,713 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 52,400 lb (23,768 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 2,053 US gal (1,709 imp gal; 7,770 L) internals plus 2x optional 450 US gal (370 imp gal; 1,700 L) drop-tanks

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney J57-P-55 afterburning turbojet engines, 11,990 lbf (53.3 kN) thrust each dry, 16,900 lbf (75 kN) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 1,134 mph (1,825 km/h, 985 kn) at 35,000 ft (11,000 m)

- Maximum speed: Mach 1.72

- Range: 1,520 mi (2,450 km, 1,320 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 58,400 ft (17,800 m)

- Wing loading: 124 lb/sq ft (610 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.74

Armament

- Missiles: 4 (originally 6)× AIM-4 Falcon, or 2× AIR-2 Genie nuclear rockets, plus 2× AIM-4 Falcon[91]

Avionics

- Hughes MG-13 fire control system

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Convair F-102 Delta Dagger

- Convair F-106 Delta Dart

- Lavochkin La-250

- McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II

- Tupolev Tu-28

Related lists

References

Citations

- ^ Francillon 1979, p. 544.

- ^ a b Pike, John. "RF-101 Voodoo". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, p. 1.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, pp. 1-2.

- ^ Davies 2019, pp. 6-7.

- ^ Francillon 1979, pp. 460–461.

- ^ a b Knaack 1982, p. 135.

- ^ a b Angelucci and Bowers 1987, p. 304.

- ^ a b Greenhalgh 1979, p. 2.

- ^ Francillon 1979, p. 461.

- ^ Davies 2019, pp. 7-8.

- ^ Dorr and Donald 1990, pp. 146, 148.

- ^ Davies 2019, p. 8.

- ^ Knaack 1982, pp. 135-136.

- ^ Peacock 1985, p. 76.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 137.

- ^ Francillon 1979, p. 538.

- ^ Knaack 1978, pp. 137–138.

- ^ a b c Francillon 1979, p. 539.

- ^ a b c d e Peacock 1985, p. 78.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 136.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, p. 5.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 138.

- ^ Francillon 1990, p. 141.

- ^ F-101A Restored, at Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum Archived 18 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, pp. 5-6.

- ^ Davies 2019, pp. 9-10.

- ^ a b Greenhalgh 1979, p. 6.

- ^ Davies 2019, p. 10.

- ^ a b Greenhalgh 1979, p. 7.

- ^ Dorr 1995, p. 172.

- ^ Davies 2019, pp. 12-13.

- ^ a b Knaack 1982, p. 139.

- ^ Knaack 1982, pp. 139-140.

- ^ a b Knaack 1982, p. 140.

- ^ Francillon 1979, p. 547.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor 1995, pp. 236–237.

- ^ a b Donald 2003, p. 55.

- ^ Dorr 1995, p. 173.

- ^ a b "Operation Sun Run". Archived 3 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved: 7 February 2008.

- ^ Davies 2019, p. 14.

- ^ Knaack 1982, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Dorr 1995, p. 187.

- ^ a b Knaack 1982, p. 141.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, p. 3.

- ^ Dorr 1995, p. 174.

- ^ a b Peacock 1985, pp. 78, 80.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, pp. 3-4.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 143.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, pp. 9-10.

- ^ Peacock 1985, p. 80.

- ^ Knaack 1982, pp. 143-144.

- ^ Knaack 1982, pp. 147-148.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 145.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, p. 26.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 144.

- ^ "ROCAF RF-101C?" taiwanairpower.org. Retrieved: 24 January 2011.

- ^ Knaack 1982, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Dorr and Donald 1990, p. 187.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 151.

- ^ a b Knaack 1982, p. 152.

- ^ a b Knaack 1978, p. 153.

- ^ Donald 2003, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Knaack 1982, pp. 152-153.

- ^ Peacock 1985, p. 95.

- ^ Dorr 1995, p. 175.

- ^ Dorr 1995, p. 178.

- ^ Knaack 1978, pp. 154-155.

- ^ "F-101B Voodoo Fighter-Interceptor History and Development US Air Force". Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine 444TH FIS Fighter-Interceptor Squadron. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ a b c Dorr 1995, p. 181.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 142.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 146.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, pp. 12-15.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, p. 19.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, pp. 10-11.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, pp. 21-25.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, pp. 40-41.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, pp. 41-43.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 147.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 148.

- ^ Greenhalgh 1979, pp. 43-44.

- ^ Knaack 1982, p. 149.

- ^ Hobson 2001, p. 269.

- ^ "Vietnam Almanac", Air Force Magazine, September 2004, p. 57.

- ^ "Air Power Classics: F/RF-101 Voodoo". Air Force Magazine, May 2008, p. 168.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Angelucci and Bowers 1987, pp. 309–310.

- ^ CSU Uses F-101B For Storm Study; N8234, nickname, 'the Gray Ghost', on display at Air Combat Museum, Topeka,KS Archived 4 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 14 October 2013

- ^ Green 1994, p. 367.

- ^ Knaack 1978, p. 156-157.

- ^ Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Falcon missile variants – AIM-4A, AIM-4B, AIM-4C only. The range was about 5 mi (4.3 nmi; 8.0 km)

Bibliography

- Angelucci, Enzo; Bowers, Peter M. (1987). The American Fighter. Sparkford, Somerset, UK: Haynes Publishing Group. ISBN 0-85429-635-2.

- Characteristics Summary, F-101B, dated 16 August 1960.

- Davies, Peter E. (2019). RF-101 Voodoo Units in Combat. Bloomsbury. ISBN 1472829158.

- Donald, David, ed. (2003). Century Jets: USAF Frontline Fighters of the Cold War. Norwalk, CT: AirTime Publishing. ISBN 1-880588-68-4.

- Dorr, Robert F. (1995). McDonnell F-88/F-101 Variant Briefing Wings of Fame Volume 1. London, UK: Aerospace Publishing. ISBN 1-874023-68-9.

- Dorr, Robert F.; Donald, David (1990). Fighters of the United States Air Force. London, UK: Temple Press/Aerospace. ISBN 0-600-55094-X.

- Francillon, René J. (1990). McDonnell Douglas Aircraft since 1920 (Vol. II) (2nd ed.). London, UK: Putnam. ISBN 978-0-85177-828-0.

- Francillon, René J. (May 1980). "It's Witchcraft: McDonnell's F-101 Voodoo". Airpower. 10 (3).

- Goodrum, Alastair (January–February 2004). "Down Range: Losses over the Wash in the 1960s and 1970s". Air Enthusiast (109): 12–17. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Gordon, Doug (May–June 1999). "Early Days of the 81st: The 81st TFW USAFE in the 1950s". Air Enthusiast (81): 36–43. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Green, William; Swanborough, Gordon (1994). The Complete Book of Fighters. London, United Kingdom: Salamander. ISBN 1-85833-777-1.

- Green, William; Swanborough, Gordon (2001). The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Greenhalgh, William (1979). The Air Force in Southeast Asia The RF-101 Voodoo 1961-1970 (PDF). Office of Air Force History. ISBN 978-1-78039-650-7.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Gunston, Bill (1981). Fighters of the Fifties. Cambridge, UK: Patrick Stephens. ISBN 0-85059-463-4.

- Hansen, Chuck (1988). U.S. Nuclear Weapons. Arlington, Texas: Aerofax. ISBN 0-517-56740-7.

- Hobson, Chris (2002). Vietnam Air Losses: United States Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps Fixed-Wing Aircraft Losses in Southeast Asia, 1961–73. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press. ISBN 1-85780-115-6.

- Jenkins, Dennis R.; Landis, Tony R. (2008). Experimental & Prototype U.S. Air Force Jet Fighters. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press. ISBN 978-1-58007-111-6.

- Jones, Lloyd S. (1975). U.S. Fighters: Army Air-Force 1925 to 1980s. Fallbrook, California: Aero Publishers. ISBN 0-8168-9201-6.

- Keaveney, Kevin (1984). McDonnell F-101B/F (Aerofax Minigraph 5). Arlington, Texas: Aerofax. ISBN 0-942548-10-8.

- Kinsey, Bert (1986). F-101 Voodoo (Detail and Scale; vol. 21). Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania: Tab Books. ISBN 0-8306-8131-0.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size (1978). Encyclopedia of US Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume 1 Post-World War II Fighters 1945–1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-59-5.

- Peacock, Lindsay (August 1985). "The One-O-Wonder". Air International. 29 (2): 75–81, 93–95. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Taylor, Michael J. H., ed. (1995). The McDonnell Voodoo. Jane's American Fighting Aircraft of the 20th Century. New York, US: Modern Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7924-5627-8.

- United States Air Force Museum Guidebook. Wright-Patterson AFC, Ohio: Air Force Association, 1975 edition.

- Walpole, Nigel (2007). Voodoo Warriors: The Story of the McDonnell Voodoo Fast-Jets. Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 1783409770.

External links

- McDonnell F-101 Voodoo articles and publications

- Baugher's F-101 Voodoo Aircraft

- USAF National Museum site: XF-88 page

- McDonnell F-101 "Voodoo" history & information

- F-101 Voodoo Survivors List of static displays, location, serial numbers, and links.