Kurd Mountain

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

| Kurd Mountain | |

|---|---|

| Kurd Dagh | |

Hills of the Kurd Mountain in Afrin | |

| Highest point | |

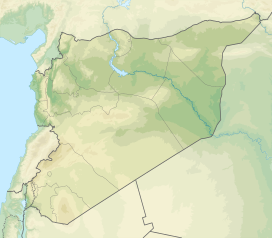

| Coordinates | 36°40′N 36°46′E / 36.667°N 36.767°E |

| Geography | |

| Location | |

Kurd Mountain or Kurd Dagh (Template:Lang-tr, officially Kurt Dağı) is a highland region in northwestern Syria and southeastern Turkey. It is located in the Aleppo Governorate of Syria and Kilis Province of Turkey. The Kurd Mountain should not be confused with the neighboring Jabal al Akrad, which is located further southwest towards the mediterranean coastline.

Location and description

Kurd Mountain is a part of the Limestone Massif of northwestern Syria. The mountain is a southern continuation into the Aleppo plateau of the highlands on the western part of the Aintab plateau. The valley of River Afrin surrounds Kurd Mountain from east and south and separates it from the plain of Aʻzāz and Mount Simeon to the east, and from Mount Harim to the south. The valley of River Aswad separates Mount Kurd from Mount Amanus to the west.[citation needed]

In Syria, it is among the four "ethnic mountains" of western Syria, along with al-Ansariyah mountains ("Mountain of the Alawites"), Jabal Turkman ("Mountain of the Turkmens") and Jabal al-Duruz ("Mountain of the Druze").

The main town is Afrin (Efrîn in Kurdish), in Syria. The area is known for its olive growing and charcoal production. The majority of the Kurd-Dagh population are Hanafi-Muslims, while most Syrian Kurds are Shafiite-Muslims. Yazidis also have a presence in the region.[1]

Demographics

As the Kurd Dagh was governed by the French, several Kurdish tribes were living in the area.[2] From the 1800s onwards, there have settled several Kurds from the Kurd Dagh to Aleppo.[3] In the 1930s, Kurdish Alevis who fled the persecution of the Turkish Army during the Dersim Massacre, settled in Mabeta.[4]

Etymology

Kurd Mountain is known locally as Çiyayê Kurmênc meaning “Mountain of the Kurmanj” after the name of the spoken dialect in the region called Kurmanji, which is one of the Kurdish dialects.[5]

The name of the mountain was mentioned in Arabic sources as Jabal al-Akrad meaning “Kurd mountain”, then with the rule of the Ottoman Empire the name was translated into the Ottoman Turkish to كرد طاغ (Kurd Dağ) in the sense of "Kurd Mountain" derived from the Turkish word طاغ - Dağ, which means Mountain. The form Kurd Dagh was used in the official Ottoman documents and remained in official circulation during the French era until the end of the first decade of Syria's independence, until the Syrian government adopted the form Jabal al-Akrad again. However, in the years of unity between Egypt and Syria, the name of Jabal al-Akrad was removed. And in 1977 the mountain was renamed to جبل العروبة Jabal al-`Uruba meaning “Mountain of Arabism” in accordance with decree 15801, which banned Kurdish names. And then it was named "Mount Aleppo" and the name Jabal al-Akrad remained circulating in textbooks as a geographical name.[6][5]

In the book of ذكرياتي عن بلاد ألف ليلة وليلة of the French commercial attaché in Aleppo. between the years 1548-1556 stated:[7]

Due to my profession in importing silk, I was traveling to Kilis, Aintab, Azaz, Jabal al-Akrad, etc.

The Turkish part was renamed officially as Kurt Dağı ("Wolf Mountain"), with a pun on the Turkish words Kürt (Kurd) and kurt (wolf).

See also

References

- ^ Açikyildiz, Birgül (23 December 2014). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. London, UK: I.B. Tauris. p. 63. ISBN 1848852746.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008-08-29). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-134-09643-5.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008-08-29). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-134-09643-5.

- ^ "derStandard.at". DER STANDARD.

- ^ a b عبدو علي, محمد (2014). جبال الكرد: دراسة جغرافية شاملة (in Arabic) (1st ed.). Afrin. p. 145.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "State policies and military actions continue to threaten further displacement" (PDF). Relief Web. p. 7. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ موسوعة حلب المقارنة، خير الدين الأسدي، ج. 3 ص. 240