Zhuge Liang

Zhuge Liang | |

|---|---|

諸葛亮 | |

An illustration of Zhuge Liang | |

| Imperial Chancellor (丞相) of Shu Han | |

| In office 229–234 | |

| In office 221–228 | |

| Monarch | Liu Bei / Liu Shan |

| General of the Right (右將軍) | |

| In office 228–229 | |

| Monarch | Liu Shan |

| Governor of Yi Province (益州牧) | |

| In office 223–234 | |

| Monarch | Liu Shan |

| Colonel-Director of Retainers (司隸校尉) | |

| In office 221–234 | |

| Monarch | Liu Bei / Liu Shan |

| Preceded by | Zhang Fei |

| Manager of the Affairs of the Masters of Writing (錄尚書事) | |

| In office 221–234 | |

| Monarch | Liu Bei / Liu Shan |

| Military Advisor General (軍師將軍) (under Liu Bei) | |

| In office 214–? | |

| Monarch | Emperor Xian of Han |

| Military Advisor General of the Household (軍師中郎將) (under Liu Bei) | |

| In office 208–? Serving with Pang Tong (210–214) | |

| Monarch | Emperor Xian of Han |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 181 Yangdu County, Langya Commandery, Han Empire (present-day Yinan County, Shandong) |

| Died | c. September 234 (aged 53)[1] Wuzhang Plains, border of Shu Han and Cao Wei (present-day Qishan County, Shaanxi) |

| Resting place | Mount Dingjun, Shaanxi |

| Spouse | Lady Huang |

| Children |

|

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Occupation | Military engineer, strategist, statesman, writer |

| Courtesy name | Kongming (孔明) |

| Posthumous name | Marquis Zhongwu (忠武侯) |

| Peerage | Marquis of Wu District (武鄉侯) |

| Nickname(s) | "Crouching Dragon" (臥龍/伏龍) |

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

Zhuge Liang (181 – c.September 234),[2] courtesy name Kǒngmíng was a Chinese military engineer, strategist, statesman, and writer. He was chancellor and later regent of the state of Shu Han during the Three Kingdoms period. He is recognised as the most accomplished strategist of his era, and has been compared to Sun Tzu, the author of The Art of War.[3] His reputation as an intelligent and learned scholar grew even while he was living in relative seclusion, earning him the nickname "Wolong" or "Fulong", meaning "Crouching Dragon" or "Sleeping Dragon". Zhuge Liang is often depicted wearing a Taoist robe and holding a hand fan made of crane feathers.[4]

Zhuge Liang was a Confucian-oriented "Legalist".[5] He liked to compare himself to the sage minister Guan Zhong and Yue Yi[5][6] developing Shu's agriculture and industry to become a regional power,[7] and attached great importance to the works of Shen Buhai and Han Fei,[8] refusing to indulge local elites and adopting strict, but fair and clear laws. In remembrance of his governance, local people maintained shrines to him for ages.[9] His name has become synonymous with wisdom and strategy in Chinese culture.[citation needed]

Early life

Zhuge Liang was born in 181 in Yangdu County, Langya Commandery (present-day Yishui, Shandong Province).[10] His family name, Zhuge, is a two-character Chinese compound family name. His father Zhuge Gui died when he was still young, and he was raised by Zhuge Xuan (a cousin of Zhuge Gui) in Yuzhang Commandery. When Zhuge Xuan was driven out of Yuzhang Commandery in 195, Zhuge Liang followed Zhuge Xuan to live with his friend, Liu Biao, the governor of Jing Province.[11]

Zhuge Liang grew to be a tall man. He enjoyed reciting the Liangfu Yin (梁父吟), a folk song popular in Shandong, his birthplace. He had a habit of comparing himself to the sage minister Guan Zhong and military leader Yue Yi. Although few people took him seriously, Zhuge Liang developed close friendships with influential members of the local literati such as Xu Shu, Cui Zhouping, Meng Jian and Shi Tao. Zhuge Liang also maintained close relations with other well-known intellectuals such as Sima Hui, Pang Degong and Huang Chengyan. Sima Hui once compared Zhuge Liang to a sleeping dragon.[11]

Huang Chengyan once told Zhuge Liang, "I heard that you're seeking a spouse. I've an ugly daughter with yellow hair and dark complexion, but her talent matches yours."[12] Zhuge Liang agreed and married Huang Chengyan's daughter.

Service under Liu Bei

When Liu Bei was residing at Xinye County and taking shelter under Jing Province's governor, Liu Biao, he visited Sima Hui, who told him, "Confucian academics and common scholars, how much do they know about current affairs? Those who analyse current affairs well are the elites. Crouching Dragon and Young Phoenix are the only ones in this region."[13] Sima Hui was referring to Zhuge Liang, whose nickname was "Crouching Dragon"; and Pang Tong, whose nickname could be translated as "Young Phoenix" or "Fledgling Phoenix" (鳳雛).

Xu Shu later recommended Zhuge Liang to Liu Bei again, and Liu wanted to ask Xu to invite Zhuge to meet him. However, Xu Shu replied, "You must visit this man in person. He cannot be invited to meet you."[14] Liu Bei succeeded in recruiting Zhuge Liang in 207 after paying three personal visits. This is contradicted in the later Annotations by Pei Songzhi which claim Zhuge Liang visited him first.[15][a] Nonetheless, "Three visits to the cottage" (三顾茅庐) became a very famous classical reference in China.

- Yi Zhongtian suggested that both the records in Sanguozhi and Weilue are the truth. The chronological order should be: Zhuge Liang approached Liu Bei first to demonstrate his wisdom. Liu Bei, having recognized Liang's talent, personally visited Liang three times to have further discussions.[16]

- The novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms portrays Liu Bei's three visits with many fictional mystic events, and narrates that only at the third visit that Liu Bei managed to meet Zhuge Liang and listened to his Longzhong Plan. However the truth is, Liu Bei managed to meet Liang in all three visits, and there were probably more visits with further discussions of the Longzhong Plan before Zhuge Liang finally decided to officially offer his services.[16]

Zhuge Liang presented the Longzhong Plan to Liu Bei and left his residence to follow Liu. Afterwards, Liu Bei became very close to Zhuge Liang and often had discussions with him. Guan Yu and Zhang Fei were displeased with their relationship and complained about it. Liu Bei explained, "Now that I have Kongming, I am like a fish that has found water. I hope you'll stop making unpleasant remarks."[17] Guan Yu and Zhang Fei then stopped complaining.

As a diplomat

In 208, Liu Biao died and was succeeded by his younger son, Liu Cong, who surrendered Jing Province to Cao Cao. When Liu Bei heard of Liu Cong's surrender, he led his followers (both troops and civilians) on an exodus southward to Xiakou, and suffered a severe defeat by Cao Cao's forces in a brief skirmish at the Battle of Changban along the way. While in Xiakou, Liu Bei sent Zhuge Liang to follow Lu Su to Jiangdong to discuss the formation of an alliance between him and Sun Quan, and Liang managed to have a meeting with Sun Quan in Chaisang.

Zhuge Liang, being able to gauge Sun Quan's personality, decided to provoke Sun Quan by telling Sun just to surrender if he could not resist Cao Wei.[18] Liang also explained that although Liu Bei was also weaker than Cao Cao, he would fight to the death instead of surrendering; moreover, Liu Bei and his allies still retained some significant forces despite the defeat at Changban, and Cao Cao's army was not as strong as it appeared to be.[19] Sun Quan was pleased with Zhuge Liang's arguments, and, together with Lu Su's analysis of the political situation and Zhou Yu's analysis of the weaknesses in Cao Cao's army, agreed to ally with Liu Bei in resisting Cao Cao. Zhuge Liang returned to Liu Bei's camp with Sun Quan's envoy, Lu Su, to make preparations for the upcoming war.

As a logistics officer

In late 208, the allied armies of Liu Bei and Sun Quan scored a decisive victory over Cao Cao's forces at the Battle of Red Cliffs. Cao Cao retreated to Ye city, while Liu Bei proceeded to conquer territories in Jiangnan, covering most of southern Jing Province. Zhuge Liang was appointed Military Advisor General of the Household (軍師中郎將). He was put in charge of governing Lingling (present day Yongzhou, Hunan), Guiyang and Changsha commanderies and collecting taxes to fund the military.

In 211, Liu Zhang, governor of Yi Province (covering present-day Sichuan and Chongqing), requested aid from Liu Bei in attacking Zhang Lu in Hanzhong Commandery. Liu Bei left Zhuge Liang, Guan Yu, Zhang Fei and others in charge of Jing Province while he led an army into Yi Province. Liu Bei promptly agreed to Liu Zhang's proposal, but secretly planned to take over Liu Zhang's land. The following year, Liu Zhang discovered Liu Bei's intention, and the two turned hostile and waged war on each other. Zhuge Liang, Zhang Fei and Zhao Yun led separate forces to reinforce Liu Bei in the attack on Yi Province's capital, Chengdu, while Guan Yu stayed behind to guard Jing Province. In 214, Liu Zhang surrendered and Liu Bei took control of Yi Province.

Liu Bei appointed Zhuge Liang as Military Advisor General (軍師將軍) and let him administer affairs of his personal office (office of the General of the Left (左將軍)). Whenever Liu Bei embarked on military campaigns, Zhuge Liang remained to defend Chengdu and ensured a steady flow of supply of troops and provisions. In 221, in response to Cao Pi's usurping of Emperor Xian's throne, Liu Bei's subordinates advised him to declare himself emperor. After initially refusing, Liu Bei was eventually persuaded by Zhuge Liang to do so and became ruler of Shu Han. Liu Bei named Zhuge Liang his chancellor and put him in charge of the imperial agency where Zhuge assumed the functions of the head of the imperial secretariat. Zhuge Liang was appointed Colonel-Director of Retainers (司隸校尉) after Zhang Fei's death.

Service under Liu Shan

In the spring of 223, Liu Bei retreated to Yong'an (present-day Fengjie County, Chongqing) after his defeat at the Battle of Xiaoting and became seriously ill. He summoned Zhuge Liang from Chengdu and said to him, "You're ten times more talented than Cao Pi, and capable of both securing the country and accomplishing our great mission. If my son can be assisted, then assist him. If he proves incompetent, then you may take over the throne."[20] Zhuge Liang replied tearfully, "I'll do my utmost and serve with unwavering loyalty until death."[21] Liu Bei then ordered his son, Liu Shan, to administer state affairs together with Zhuge Liang and regard Zhuge as his father.

There are controversies over the last statement of Liu Bei on Zhuge Liang's "take over the throne" (君可自取). Yi Zhongtian in his "Analysis of the Three Kingdoms" presented several interpretations of Liu Bei's message. Chen Shou commented that Liu Bei wholeheartly trusted Zhuge Liang and permitted Liang to "take over" literally. Some argued that Liu Bei said that only to test Zhuge Liang's loyalty as his brother, Zhuge Jin, was working for Eastern Wu. Other commented that the "take over the throne" part did not mean Zhuge Liang was allowed take the throne for himself, but he was permitted to, when the situation demanded, replace Liu Shan with other of Liu Bei's living sons such as Liu Yong and Liu Li.

Holding power as a regent

After Liu Bei's death, Liu Shan ascended to the throne of Shu Han. He granted Zhuge Liang the title "Marquis of Wu District" (武鄉侯) and created an office for him as a Chancellor. Not long later, Zhuge Liang was appointed Governor of Yi Province – the region which included most of Shu Han's territory.

Being both the Chancellor (directly managing the bureaucrat officers) and provincial governor (directly managing the common people) meant that both the magistrates and common people, i.e. all of the state affairs, were in the hand of Zhuge Liang. Having an independent Chancellery Office (with attached independent subordinates) meant that Zhuge Liang's authority was relatively independent of the emperor's authority. In other words, just like in Sanguozhi said, all of Shu Han's affairs, trivial or vital, were directly handled by Zhuge Liang, and the emperor Liu Shan was just a nominal leader. Moreover, the emperor himself was strictly educated and supervised by Zhuge Liang. This situation was maintained until Liang's death.

There are many attempts who tried to explain why Zhuge Liang refused to return the authority to Liu Shan. Yi Zhongtian proposed three reasons:[22]

- Zhuge Liang supported the model of the emperor only indirectly lead the country and have a Chancellor to handle the affairs in his name, similar to the situation at the early period of Western Han. On Liang's opinion, if the emperor directly handled the affairs, then there is no one to be blamed if problems occurred, but if a representative Chancellor handled things then the emperor could have an interpellation against the Chancellor in the case of failure.

- Zhuge Liang stubbornly thought that Liu Shan was not experienced enough to directly handle the state affairs, hence Liang decided to do things himself to make sure no mistakes happened.

- The situation of Shu Han was indeed very complicated at that time which required extremely well-planned solutions. An inexperienced Liu Shan could not handle such challenging problems, but Zhuge Liang could.

Economic reforms

Yi Province's wealthy families, uncurbed by the previous governors, freely exploited the common people and had an extravagant life. As a result, poverty was widespread, and economical-political reform was the most important concern for Zhuge Liang. A robust economic foundation was also necessary to enhance the people's loyalty to Shu Han regime and properly support the future's expeditions against Cao Wei. Therefore, Zhuge Liang made it clear that the core value of his policy was to stabilize and improve the life of the people.[23]

Zhuge Liang's new policies was enacted right from the time of Liu Bei and continued in the time of Liu Shan. He purged the corrupted officials, relieved taxes, and restricted the nobilities's abuse of power against the common people. Forced labours and military mobilization were also reduced and rescheduled to avoid the disruption of agriculture activities, and Cao Cao's tuntian system was implemented extensively to increase food production output. Agriculture dykes were significantly rebuilt and repaired, including the famous Zhuge dyke northern of Chengdu. Thanks to the reform, Shu Han agriculture production grew significantly and was able to sustain her military activities.

Salt manufacture, silk production, and steelmaking – three notable economic activities of Shu region – also attracted Zhuge Liang's attention. Liu Bei, following the proposal of Zhuge Liang, created specialized bureaus for salt and steelmaking management, first directed by Wang Lian and Zhang Yi, respectively. A specialized silk management bureau was also established, hence Chengdu was named as "the city of Silk". Sanguozhi reported that salt production in Shu Han was highly prosperous and generated significant income to the government. Fu Yuan, a well-known local metalsmith, was entrusted by Zhuge Liang in metallurgy research and managed to improve the techniques in crafting steel weapons for Shu Han army. Silk production also had significant growth, at the end of Shu Han regime it managed to accumulated 200,000 pieces of silk in the national treasure. Zhuge Liang's family plantation also had 800 mulberry plants for silkworm feeding.

Due to political turmoil, monetary systems at the end of the Han dynasty were in severe turbulence. When establishing themselves in the Yi Province, Liu Bei and Zhuge Liang, following the advice of Liu Ba, enacted successful monetary reforms. The new Shu Han currency was not only smoothly circulated within its borders, but also popular in the neighboring Jing province. Meanwhile, similar policies of Cao Cao, Cao Pi, Cao Rui and Sun Quan were marred by difficulties and produced limited results.

Legal and moral reforms

Zhuge Liang strongly supported the rule of law in Shu Han. Yi Zhongtian commented that "Rule of Laws" together with "Nominal rule of the Monarch and direct rule of the Chancellor" are two important legacy of Zhuge Liang which were pitifully forgotten by many people.[24]

After Liu Bei entered Yi province, Zhuge Liang, together with Fa Zheng, Liu Ba, Li Yan and Yi Ji, wrote the legal codes for Shu Han.[25]

In order to curb the corruption and associated decadences of the local Yi nobility, Zhuge Liang enacted a Legalist policy with strict but fair and transparent laws, and restricted the power of wealthy families. Zhuge Liang was willing to punish high-ranked magistrates such as Li Yan, Liang's close associates such as Ma Su, and even willing to demote himself to keep the legal orders. However Liang also refrained from abusing punishment and required extreme caution in law enforcement. Xi Zuochi praised Liang's policy of legal rule, that "since the era of Qin and Han there had been no one as equal." Even punished magistrates like Li Yan and Liao Li put Zhuge Liang in high regards and strongly believed that Liang would re-employ them after the punishment was enough.[26][23]

Zhuge Liang also promoted moral conduct and himself had a strict and stoic life as a model. He did not own excessive assets, refrained from luxurious spending, relied mainly on government salary. Shu Han's magistrates, like Deng Zhi, Fei Yi, Jiang Wei, Zhang Yi also followed suit, strictly abided by the law and the moral codes, enabled the Shu government to maintain a high level of transparency and integrity.[23] Yi Zhongtian praised Shu Han as the best model of "rational rule" amongst the Three Kingdoms, and it is the incorruptibility and transparency of Zhuge Liang and his associates that kept Shu Han from collapsing in disregard of the heavy expenditure burden.[27]

Not everybody was happy with such Legalist policy. Guo Chong's comment on Liang's policy was that it was "cruel" and "exploitative", that "everybody from the noble to the commoner" was upset. Pei Songzhi disagreed with such comments because Zhuge Liang's law enforcement was appropriate and could never be "exploitative".[28] That also contradicted Chen Shou's comment that "nobody was upset despite the strict laws". Yi Zhongtian commented that both contradicted assessments are correct, as Shu people were happy about Liang's fairness and transparency, but some of them were also upset about Liang's overstrictness. Moreover, Zhuge Liang's fairness and legal rule inevitably suppressed the local nobility, prevented them from abusing their power and manipulate politics and public opinion. That is the reason why many of the local Shu intellegistia tacitly endorsed the invasion of Wei against Shu, although they also respected Zhuge Liang.[29] This is supported by contemporary sources, including Zhang Wen[30] and Sun Quan. Yuan Zhun of the Jin dynasty also highly appraised Zhuge Liang's administration skills and popularity,[31] where people would still sing praises to Zhuge Liang decades after his death.[32]

Education and talents enrollment policy

Zhuge Liang highly appreciated talents, hence he paid strong attention to education in order to cultivate and recruit more talented magistrates for Shu Han government. Liang established a position of Aide of Learning Encouragement (勸斈從事), held by many prominent local intelligentsia such as Qiao Zhou. Qiao Zhou held this post for a very long time and was very influential; one of his students, Chen Shou, was the author of Sanguozhi. Later Zhuge Liang established a Great Education Residence (太斈府), a training facility using Confucian literature works as textbooks. Liang also created many "reading book residences" both in Chengdu and in the frontline during the northern expeditions; such facilities functioned as places for discussions of various topics, and via such discussions talented people could be discovered and recruited. Yao Tian, Shu Han's governor of Guanghan district, managed to recommend many talents to the government, hence he received lavish praise from Zhuge Liang.[33]

Zhuge Liang also established "Discussion Bureau" mechanism to gather all the discussions of a certain policy, and encourage the magistrate to accept the criticisms of their subordinates to make a good decisions, and also to utilize all the talents of employees. Zhuge Liang carried out a meritocracy policy, promoted and assessed people based on what they did and could do rather than their fame or background.[33]

Diplomatic missions in Eastern Wu

At the same time, the commanderies in Nanzhong rebelled against Shu, but Zhuge Liang did not send troops to suppress the revolt as Liu Bei's death was still recent. Liu Bei had been persuaded after his defeat by Lu Xun that an alliance with Wu was necessary. Zhuge sent Deng Zhi and Chen Zhen to make peace with Eastern Wu and reentered an alliance with Wu. Zhuge Liang would consistently send envoys to Wu to improve diplomatic relations between the two states.

In 229, Sun Quan proclaimed himself as emperor. This act angered many of the Shu Han court officials who considered the rulers of Shu Han, direct descendants of former Han dynasty, were the only ones could have legitimate claim of the imperial throne. Some of Shu Han's officials even suggested severing the ties between Shu and Wu. However Zhuge Liang commented that Shu-Wu alliance was still necessary, hence Sun Quan's "treachery" could be temporarily left aside. A Shu Han emissary was sent to congratulate Sun Quan and strengthen the relationship between two allies.

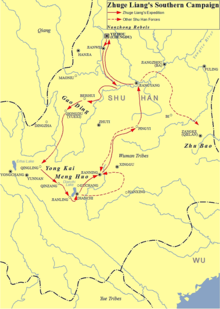

Southern Campaign

During his reign as regent, Zhuge Liang set Shu's objective as the restoration of the Han dynasty, which, from Shu's point of view, had been usurped by the state of Cao Wei. He felt that in order to attack Wei, a complete unification of Shu was first needed.[34] Zhuge Liang was worried that the local clans would work with the Nanman tribes in Nanzhong to stage a revolt. Fearing the possibility that the peasants might rebel and press into areas surrounding the capital Chengdu while he was attacking Wei in the north, Zhuge Liang decided to pacify the southern tribes first.

In the spring of 225, regional clans, including Yong, Gao, Zhu and Meng, had taken control of some cities in the south, so Zhuge Liang led an expedition force to Nanzhong. Ma Su proposed that they should attempt to win the hearts of the Nanman and rally their support instead of using military force to subdue them. Zhuge Liang heeded Ma Su's advice and defeated the rebel leader, Meng Huo, on seven occasions, as it was claimed in later histories such as the Chronicles of Huayang. He released Meng Huo each time in order to achieve Meng's genuine surrender.[35] The story about Meng Huo's seven captures is recently questioned by many modern academics, including historians such as Miao Yue, Tan Liangxiao, and Zhang Hualan.

Realising he had no chance to win, Meng Huo pledged allegiance to Shu, and was appointed by Zhuge Liang as governor of the region to keep the populace content and secure the southern Shu border. This would ensure that the future Northern Expeditions would proceed without internal disruptions.[34] Rich and abundant resources acquired from Nanzhong were used to fund Shu's military and the state became more prosperous.

Northern Expeditions and death

After pacifying the Nanman, Zhuge Liang ordered the Shu military to make preparations for a large scale offensive on Wei. In 227, while in Hanzhong, he wrote a memorial, titled Chu Shi Biao, to Liu Shan, stating his rationale for the campaign and giving advice to the emperor on good governance. From 228 until his death in c.September 234, Zhuge Liang launched a total of five Northern Expeditions against Wei, all except one of which failed. During the first Northern Expedition, Zhuge Liang persuaded Jiang Wei, a young Wei military officer, to surrender and defect to his side.[36] Jiang Wei became a prominent general of Shu later and continued Zhuge Liang's legacy of an aggressive foreign policy against Wei. The other permanent gains by Shu were the conquests of the impoverished Wudu and Yinping commanderies, as well as the relocation of Wei citizens to Shu territories on occasion.[36] During the first expedition the veteran commander Wei Yan proposed to lead a detachment of 10,000 troops to launch a surprise attack through Ziwu Valley. Such a plan was highly risky, but in the case of success it could result in a decisive victory. The plan was rejected by an overcautious Zhuge Liang, which upset Wei Yan.

The first expedition took Cao Wei by surprise and initially proceeded smoothly, however Shu Han troops commanded by Ma Su suffered a strategic defeat at battle of Jieting, resulting in the total failure of the expedition. Zhuge Liang, as a punishment, had Ma Su executed, and had himself demoted by three levels. In second expedition, Shu army launched an unsuccessful attack at the key fortress Chencang and had to withdraw when Wei reinforcements arrived. The pursuing Wei general Wang Shuang was killed by a Shu ambush, though. The third expedition managed to capture Wudu and Yinping, two depopulated commanderies used as military bridgeheads for further attacks. Cao Wei tried a counter-attack in 230, which also ended in failure.

The fourth expedition (231) marked the first deployment of wooden oxen for supply transportation, and the first time Zhuge Liang met Sima Yi in the battlefield. Zhuge Liang sent the bulk of his army to Mount Qi and lead a detachment to Shanggui for grain harvest. Guo Huai and Fei Yan's attempt of intervention ended in failure and Shu forces managed to harvest most of the wheat. Sima Yi decided to use the Fabian strategy and kept the defensive stance. Zhuge Liang retreated to Lucheng at the eastern side of Mount Qi to lure Sima Yi. The also cautious Sima Yi initially did not take the bait, but relented under the pressure of his subordinates. Cao Wei's attack ended in a disaster, though, hence Sima Yi resumed his defensive stance, this time persistently. Zhuge Liang could not exploit his victory with a major offensive due to a dwindling food supply as adverse weather prevented Shu's logistics from delivering materiel on schedule. Shu troops had no choice but a total retreat, although they managed to kill general Zhang He in another ambush.

Learning from the experiences, Zhuge Liang spent great efforts in mitigating the logistic problem of the Shu army. He improved the wooden ox into the flowing horse, build an extraordinary huge supply storage facility, and carried out large-scale agriculture production in the northern area. He also successfully asked for a coordinated attack from Eastern Wu. After two years of preparation, in 234 Liang launched his last expedition. The Shu army garrisoned at the Wuzhang Plain (near modern-day Baoji, Shaanxi) and implemented military plantation (tuntian) here for long-term food supplement. From the Cao Wei side, Sima Yi again persistently adapted the Fabian strategy and managed to quell the protest from his subordinate. Zhuge Liang attempted to make many provocations but all failed. Straining his energy on military matters big and small, Zhuge Liang fell seriously ill and eventually died in camp at the age of 53. Before his death, Zhuge Liang recommended Jiang Wan and Fei Yi to succeed him as regent of Shu.

Sima Yi, hearing the news of Zhuge Liang's death and Shu army's subsequent withdrawal, quickly launched a pursuit. However the Shu rearguard feigned a counterattack, which fooled the overcautious Sima Yi into believing that Zhuge Liang was still alive and had planned an ambush. The Wei army halted and the Shu army successfully retreated. That incident gave rise to the popular saying "A dead Zhuge (Liang) scared away a living Zhongda.[b]" When told of the saying, Sima Yi replied: "I can predict the thoughts of the living but I can't predict those of the dead."[37]

Burial

Zhuge Liang, according to his dying wish, was buried on Mount Dingjun with a modest funeral and tomb, using no luxurious and expensive material. Liang was posthumously granted the title "Marquis Zhongwu" (忠武侯; literally "loyal and martial marquis") by Liu Shan. Zhuge Liang once wrote to Liu Shan promising that he would have a stoic life with no excessive and no luxurious assets as a model for the country. After Zhuge Liang's death, people had his property checked, which verified his claims.[38]

The death of Zhuge Liang was widely mourned by the Shu Han people. Initially, the mourning and worship for Zhuge Liang was done arbitrarily by the people since neither official temple nor legal worship protocol for Zhuge Liang had been established yet,[39] which upset the public opinion. Hence in spring 263, a temple for Zhuge Liang was built in Mianyang, near his tomb.[40]

Family and descendants

Zhuge Liang's ancestor, Zhuge Feng (諸葛豐), served as the Colonel-Director of Retainers during the reign of Emperor Yuan of the Han dynasty. Zhuge Liang's father, Zhuge Gui (諸葛珪), served as an assistant officer in Mount Tai Commandery in the late Han dynasty. Zhuge Liang's cousin-uncle, Zhuge Xuan, who raised Zhuge Liang and Zhuge Jun, served as the Administrator of Yuzhang Commandery before serving under Liu Biao, the Governor of Jing Province.

Zhuge Liang had an elder brother, a younger brother, and two elder sisters. His elder brother, Zhuge Jin, served under the warlord Sun Quan and later in the state of Eastern Wu. His younger brother, Zhuge Jun (諸葛均), served in the state of Shu Han. One of Zhuge Liang's sisters married Pang Shanmin, a cousin of Pang Tong, while the other sister married a member of the prominent Kuai family headed by Kuai Liang and Kuai Yue in Xiangyang Commandery.

Zhuge Liang married the daughter of Huang Chengyan. She was a maternal niece of Lady Cai (Jing Province's Liu Biao's wife) because her mother (Huang Chengyan's wife) was Lady Cai's younger sister. Although her name was not recorded in history, she is commonly referred to by the name "Huang Yueying" in popular culture.

Zhuge Liang had at least two sons. His elder son, Zhuge Zhan, served as a general in Shu and was killed in action during the Conquest of Shu by Wei. His younger son, Zhuge Huai (諸葛懷), lived as a commoner during the Jin dynasty. Zhuge Liang initially had no sons, so he adopted his nephew, Zhuge Qiao (Zhuge Jin's son). Zhuge Qiao served in Shu and died at a relatively young age. According to legend, Zhuge Liang had a daughter, Zhuge Guo (諸葛果), but her existence is disputed by historians.

Zhuge Qiao's son, Zhuge Pan (諸葛攀), returned to Eastern Wu after Zhuge Ke's death to continue Zhuge Jin's family line there. Zhuge Zhan had three sons. The eldest, Zhuge Shang, served Shu and was killed in action together with his father. The second, Zhuge Jing (諸葛京), moved to Hedong Commandery in 264 with Zhuge Pan's son, Zhuge Xian (諸葛顯), and came to serve the Jin dynasty later. The youngest was Zhuge Zhi (諸葛質).Some Chinese historians believe that Zhuge Zhi is just a fictional character.

Zhuge Dan, one of Zhuge Liang's cousins, served in the state of Cao Wei and masterminded the third of the Three Rebellions in Shouchun. He was killed after his defeat.

Legacy

Inventions

Although the invention of the repeating crossbow has often been attributed to Zhuge Liang, he had nothing to do with it. This misconception is based on a record attributing improvements to the multiple bolt crossbows to him.[41]

Zhuge Liang is also credited with constructing the Stone Sentinel Maze, an array of stone piles that is said to produce supernatural phenomena, located near Baidicheng.[42]

An early type of hot air balloon used for military signalling, known as the Kongming lantern, is also named after him.[43] It was said to be invented by Zhuge Liang when he was trapped by Sima Yi in Pingyang. Friendly forces nearby saw the message on the lantern paper covering and came to Zhuge Liang's aid. Another belief is that the lantern resembled Zhuge Liang's headdress, so it was named after him.

Literary works

Some books popularly attributed to Zhuge Liang can be found today. For example, the Thirty-Six Stratagems, and Mastering the Art of War (not to be confused with Sun Tzu's The Art of War) are two commonly available works attributed to Zhuge Liang. Supposedly, his mastery of infantry and cavalry formation tactics, based on the Taoist classic I Ching, were unrivalled. His memorial, the Chu Shi Biao, written prior to the Northern Expeditions, provided a salutary reflection of his unwavering loyalty to the state of Shu.[44] The memorial moved some readers to tears. In addition, he wrote Admonition to His Son (諸葛亮誡子書) in which he reflected on his humbleness and frugality in pursuit of a meaningful life.[45]

Zhuge Liang is also the subject of many Chinese literary works. A poem by Du Fu, a prolific Tang dynasty poet, was written in memory of Zhuge Liang whose legacy of unwavering dedication seems to have been forgotten in Du Fu's generation (judging by the description of Zhuge Liang' unkept temple). Some historians believe that Du Fu had compared himself with Zhuge Liang in the poem.[citation needed] The full text is:

| 蜀相 (武侯祠)

丞相祠堂何處尋? |

Premier of Shu (Temple of the Marquis of Wu)

Where to seek the temple of the noble Premier? |

Another poem of Du Fu was also written to praise Zhuge Liang at his Baidicheng temple.

| 蜀相 (武侯祠)

武侯廟 |

Temple of the Marquis of Wu

Zhuge's fame overshadow the universe |

Du Fu's quatrain "Eightfold Battle Formation" (八陣圖) about Zhuge Liang's Stone Sentinel Maze, is collected in the Three Hundred Tang Poems.

Notable quotes

The phrase "The Han and the Evil do not stand together" (simplified Chinese: 汉贼不两立; traditional Chinese: 漢賊不兩立; pinyin: Hàn zéi bù liǎng lì) from the Later Chu Shi Biao is often used to draw a line in the sand and declare a situation where one cannot stand with evil. Notably, this phrase was Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek's favorite quote to invoke to justify his anti-communism ideology.

Another phrase "with deference and prudence, to the state of one's depletion; it's never finished until one's death" (simplified Chinese: 鞠躬尽瘁,死而后已; traditional Chinese: 鞠躬盡瘁,死而後已; pinyin: jū gōng jìn cuì, sǐ ér hòu yǐ) from the Later Chu Shi Biao is often used to describe one's commitment and perseverance to strive to the utmost.

One famous line of poem, "Who is the first, awakened from the Great Dream? As always, I'm the one who knows." (simplified Chinese: 大梦谁先觉?平生我自知.; traditional Chinese: 大夢誰先覺?平生我自知.; pinyin: dà mèng shuí xiān jué ? píng shēng wǒ zì zhī), was also attributed to Zhuge Liang.

"Without modest simplicity, one cannot brighten volition; Without tranquility and serenity, one cannot reach far" (simplified Chinese: 非淡泊无以明志,非宁静无以致远; traditional Chinese: 非淡泊無以明志,非寧靜無以致遠), a well-known maxim authored by Zhuge Liang, has been popular in educational institutions in China for thousands of years.

In Romance of the Three Kingdoms

The wisdom of Zhuge Liang was popularised by the historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, written by Luo Guanzhong during the Ming dynasty. In it, Zhuge Liang is described to be able to perform fantastical achievements such as summoning advantageous winds and devising magical stone mazes.

There is great confusion on whether the stories are historical or fictional. At least, the Empty Fort Strategy is based on historical records, albeit not attributed to Zhuge Liang historically.[3] For Chinese people, the question is largely irrelevant, as the Zhuge Liang of lore is regardless seen as a mastermind, whose examples continue to influence many layers of Chinese society. They are also argued, together with Sun Tzu's The Art of War, to still greatly influence the modern Chinese strategical, military and everyday thinking.[3]

See the following for the stories in Romance of the Three Kingdoms involving Zhuge Liang.

- Three visits to the thatched cottage

- Battle of Bowang

- Zhuge Liang's diplomatic mission to Jiangdong

- Borrowing arrows with straw boats

- Zhuge Liang summons an eastern wind

- Battle of Jiameng Pass

- Battle of Xiaoting

- Meng Huo captured and released seven times

- Empty fort strategy

Events before Zhuge Liang's death

When Zhuge Liang fell critically ill during the Battle of Wuzhang Plains, he attempted to extend his lifespan by 12 years through a ritual. However, he failed when the ritual was disrupted by Wei Yan, who rushed in to warn him about the enemy's advance.[46] Before his death, Zhuge Liang also passed his 24 Volumes on Military Strategy (兵法二十四篇) to Jiang Wei,[c] who would continue his legacy and lead another eleven campaigns against the state of Cao Wei (曹魏).

Worship of Zhuge Liang

There are many temples and shrines built to commemorate Zhuge Liang. Some of the most famous ones include the Temple of the Marquis of Wu in Chengdu, and the Temple of the Marquis of Wu in Baidicheng.

-

The Temple of Marquis Wu of Wuzhang Plains is dedicated to Zhuge Liang

In 760, when Emperor Suzong of the Tang dynasty built a temple to honour Jiang Ziya, he had sculptures of Zhuge Liang and another nine famous historical military generals/strategists – Bai Qi, Han Xin, Li Jing, Li Shiji, Zhang Liang, Tian Rangju, Sun Tzu, Wu Qi and Yue Yi – placed in the temple flanking Jiang Ziya's statue.[48]

Zhuge Liang is also sometimes venerated as a door god at Chinese and Taoist temples, usually in partnership with Sima Yi of Wei.[citation needed]

In popular culture

Movie and television

Notable actors who have portrayed Zhuge Liang in Movie and television include: Adam Cheng, in The Legendary Prime Minister – Zhuge Liang (1985); Li Fazeng, in Zhuge Liang (1985); Tang Guoqiang, in Romance of the Three Kingdoms (1994); Pu Cunxin, in Three Kingdoms: Resurrection of the Dragon (2008); Takeshi Kaneshiro, in Red Cliff (2008–09); Lu Yi, in Three Kingdoms (2010); Raymond Lam, in Three Kingdoms RPG (2012); Wang Luoyong, in The Advisors Alliance (2017).

References In Fiction

In [Death March to the Parallel World Rhapsody], volume 13, a character is described as carrying a "Zhuge Liang-style" hand fan.

Video games

Zhuge Liang's reputation for being an unparalleled genius is also emphasised in his portrayal in video games. Reflecting his status as the most highly regarded strategist in Romance of the Three Kingdoms, games such as Destiny of an Emperor and Koei's Romance of the Three Kingdoms game series place Zhuge Liang's intelligence statistic as the highest of all characters. He is also a playable character in Koei's Dynasty Warriors, Dynasty Tactics and Kessen II. He also appears in Warriors Orochi, a crossover between Dynasty Warriors and Samurai Warriors. Additionally, he is a playable character in the video game Total War: Three Kingdoms.

See also

Notes

- ^ Some other historical sources contradict this story, claiming that it was Zhuge Liang who visited Liu Bei first and offered his services. This account comes from the Weilue, quoted by Pei Songzhi in his annotations to Chen Shou's Sanguozhi, vol. 35, p. 913. See also Henry, Eric (December 1992). "Chu-ko Liang in the Eyes of his Contemporaries". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 52 (2): 593–96. doi:10.2307/2719173. JSTOR 2719173.

- ^ "Zhongda" was Sima Yi's courtesy name.

- ^ In note 1 of chapter 104 – see p. 2189 – Roberts mentions the Zhuge Liang ji (諸葛亮集; AD 274), which Chen Shou compiled.[47]

References

Citations

- ^ Zhuge Liang's biography in Records of the Three Kingdoms mentioned that he died at the age of 54 (by East Asian age reckoning) in the 8th month of the 12th year of the Jianxing era (223–237) in Liu Shan's reign. This month corresponds to 11 Sep to 10 Oct 234 in the Julian calendar. ([建興]十二年 ... 其年八月,亮疾病,卒于軍,時年五十四。) By calculation, his birth year should be around 181.

- ^ de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). A biographical dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Brill. p. 1172. ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- ^ a b c Nojonen, Matti (2009). Jymäyttämisen taito. Strategiaoppeja muinaisesta Kiinasta [The Art of Deception. Strategy lessons from Ancient China. Helsinki, Finland: Gaudeamus. ISBN 978-952-495-089-3.

- ^ "Ancient Cultivation Stories: Zhuge Liang's Cultivation Practise". ClearHarmony.net. 28 July 2005. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ a b Dillon, Michael (1998). China: A Cultural and Historical Dictionary. p. 389.

- ^ Baogang Guo 2008 p. 38. China in Search of a Harmonious Society. https://books.google.com/books?id=UkoStC-S-AMC&pg=PA38

- ^ Deng, Yinke (2007). History of China. p. 65. ISBN 978-7508510989.

- ^ Legalist references

- Paul R. Goldin 2013. Dao Companion to the Han Feizi p.271. https://books.google.com/books?id=l25hjMyCfnEC&dq=%22han+fei%22+%22zhuge+liang%22&pg=PA271

- Guo, Baogang (2008). China in Search of a Harmonious Society. p38. https://books.google.com/books?id=UkoStC-S-AMC&pg=PA38

- Pines, Yuri (10 December 2014). "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy". Epilogue: Legalism in Chinese History. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/chinese-legalism/

- Current Shen Buhai reference is less strong, but Han Feizi is rooted in Shen's administrative doctrine regardless; Shen does not imply Han Fei, but Han Fei implies Shen

- ^ Auyang, Sunny (2015). The Dragon and the Eagle. p. 290.

- ^ Knechtges (2014), p. 2329.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 1172.

- ^ (聞君擇婦;身有醜女,黃頭黑色,而才堪相配。) Sanguozhi vol. 35.

- ^ (儒生俗士,豈識時務?識時務者為俊傑。此間自有卧龍、鳳雛。) Sanguozhi vol. 35.

- ^ (此人可就見,不可屈致也。將軍宜枉駕顧之。) Sanguozhi vol. 35.

- ^ "Zhuge Liang – Kong Ming, The Original Hidden Dragon". JadeDragon.com. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ a b Yi Zhongtian. Analysis of the Three Kingdoms, Vol. 1, Vietnamese translation. Publisher of People's Public Security, 2010. Chapter 16: Three visits to the cottage.

- ^ (孤之有孔明,猶魚之有水也。願諸君勿復言。) Sanguozhi vol. 35.

- ^ "If you can use the forces of Wuyue to resist the central government, why not break ties (with Cao Cao) in advance? If you cannot oppose, why not demobilise the troops, discard your armour and surrender to the north?" (若能以吳、越之眾與中國抗衡,不如早與之絕﹔若不能當,何不案兵束甲,北面而事之!) Chen Shou. Records of Three Kingdoms, Volume 35, Biography of Zhuge Liang.

- ^ Chen Wende. Great story of Kongming Zhuge Liang. Vietnamese translation: Nguyễn Quốc Thái. Labor Publisher. 2018. Chapter 6: Sun – Liu alliance.

- ^ (君才十倍曹丕,必能安國,終定大事。若嗣子可輔,輔之;如其不才,君可自取。) Sanguozhi vol. 35.

- ^ (臣敢竭股肱之力,效忠貞之節,繼之以死!) Sanguozhi vol. 35.

- ^ Yi Zhongtian. Analysis of the Three Kingdoms, Vol. 2, Vietnamese translation. Publisher of People's Public Security, 2010. Chapter 37: A special duo of lord and subordinate

- ^ a b c Chen Wende. Great story of Kongming Zhuge Liang. Vietnamese translation: Nguyễn Quốc Thái. Labor Publisher. 2018. Chapter 27: Agriculture and Legalism.

- ^ Yi Zhongtian. Analysis of the Three Kingdoms, vol. 2, Vietnamese translation. Publisher of People's Public Security, 2010. Epilouge: The Billowing Yangtze River Flows East.

- ^ ([伊籍]与诸葛亮、法正、刘巴、李严共造《蜀科》;《蜀科》之制,由此五人焉。) Sanguozhi, vol. 38

- ^ (诸葛亮又与平子丰教曰:“吾与君父子戮力以奖汉室,此神明所闻,非但人知之也。表都护典汉中,委君于东关者,不与人议也。谓至心感动,终始可保,何图中乖乎!昔楚卿屡绌,亦乃克复,思道则福,应自然之数也。原宽慰都护,勤追前阙。今虽解任,形业失故,奴婢宾客百数十人,君以中郎参军居府,方之气类,犹为上家。若都护思负一意,君与公琰推心从事者,否可复通,逝可复还也。详思斯戒,明吾用心,临书长叹,涕泣而已。”) Sanguozhi, vol. 40

- ^ Yi Zhongtian. Analysis of the Three Kingdoms, vol. 2, Vietnamese translation. Publisher of People's Public Security, 2010. Chapter 42: Passed away in Helplessness. Chapter 48: Convergence of Separated Lines.

- ^ (臣松之以为亮之异美,诚所愿闻,然冲之所说,实皆可疑,谨随事难之如左:其《一事》曰:亮刑法峻急,刻剥百姓,自君子小人咸怀怨叹,法正谏曰:“昔高祖入关,约法三章,秦民知德,今君假借威力,跨据一州,初有其国,未垂惠抚;且客主之义,宜相降下,愿缓刑弛禁,以慰其望。”亮答曰;“君知其一,未知其二。秦以无道,政苛民怨,匹夫大呼,天下土崩,高祖因之,可以弘济。刘璋暗弱,自焉已来有累世之恩,文法羁縻,互相承奉,德政不举,威刑不肃。蜀土人士,专权自恣,君臣之道,渐以陵替;宠之以位,位极则贱,顺之以恩,恩竭则慢。所以致弊,实由于此。吾今威之以法,法行则知恩,限之以爵,爵加则知荣;荣恩并济,上下有节。为治之要,于斯而著。”) Sanguozhi, vol. 35

- ^ Yi Zhongtian. Analysis of the Three Kingdoms, vol. 2, Vietnamese translation. Publisher of People's Public Security, 2010. Chapter 42: Passed away in Helplessness. Chapter 48: Convergence of Separated Lines. Epilouge: The Billowing Yangtze River Flows East.

- ^ (权既阴衔温称美蜀政,又嫌其声名大盛,众庶炫惑,恐终不为己用,思有以中伤之) Sanguozhi vol. 57.

- ^ (亮之治蜀,田畴辟,仓廪实,器械利,蓄积饶,朝会不华,路无醉人。) Yuanzi annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 35.

- ^ (亮死至今数十年,国人歌思,如周人之思召公也,孔子曰“雍也可使南面”,诸葛亮有焉。) Yuanzi annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 35.

- ^ a b Chen Wende. Great story of Kongming Zhuge Liang. Vietnamese translation: Nguyễn Quốc Thái. Labor Publisher. 2018. Chapter 28: Talents promotion.

- ^ a b Zhuge, Liang; Zhang, Zhu; Duan, Xizhong; Wen, Xuchu (1960). 諸葛亮集 [Collected works of Zhuge Liang] (in Chinese). Beijing: Zhonghua Publishing. OCLC 21994628.

- ^ Huang, Walter Ta (1967). Seven times freed. New York: Vantage Press. OCLC 2237071.

- ^ a b Luo, Zhizhong (2003). 諸葛亮 (in Chinese). Taichung, Taiwan: Hao du chu ban you xian gong si. ISBN 978-957-455-576-5. OCLC 55511668.

- ^ (杨仪等整军而出,百姓奔告宣王,宣王追焉。姜维令仪反旗鸣鼓,若将向宣王者,宣王乃退,不敢逼。于是仪结陈而去,入谷然后发丧。宣王之退也,百姓为之谚曰:“死诸葛走生仲达。”或以告宣王,宣王曰:“吾能料生,不便料死也。”) Hanjin Chunqiu annotation in Sanguozhi, vol. 35

- ^ (初,亮自表后主曰:“成都有桑八百株,薄田十五顷,子弟衣食,自有馀饶。至于臣在外任,无别调度,随身衣食,悉仰于官,不别治生,以长尺寸。若臣死之日,不使内有馀帛,外有赢财,以负陛下。”及卒,如其所言。) Sanguozhi, vol. 35

- ^ In his works, Sima Guang noted that during the Han era, only emperors were worshiped at temples. (及秦非笑圣人荡灭典礼,务尊君卑臣,于是天子之外无敢营宗庙者.) Song Wen Jian (宋文鉴; Siku Quanshu edition), vol. 76 and Chuan Jia Ji (传家集; Siku Quanshu edition), vol. 79

- ^ (景耀六年春,诏为亮立庙于沔阳) Sanguozhi, vol. 35

- ^ Needham (1994), p. 8.

- ^ Zhuge Liang; Liu Ji; Thomas Cleary (1989). Mastering the art of war. Boston: Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-0-87773-513-7. OCLC 19814956.

- ^ Yinke Deng (2005). Ancient Chinese inventions. China Intercontinental Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-7-5085-0837-5.

Kongming balloon.

- ^ "Zhuge Liang and the Qin". www.silkqin.com. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ "Tranquility_Aspiration". Vincent's Calligraphy. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ Luo, Guanzhong (2007). Three Kingdoms: A Historical Novel: Volume IV. Translated by Roberts, Moss. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. pp. 1886–88. ISBN 978-7-119-00590-4.

- ^ Luo, Guanzhong (2007). Three Kingdoms: A Historical Novel: Volume IV. Translated by Roberts, Moss. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. p. 1889. ISBN 978-7-119-00590-4.

- ^ (上元元年,尊太公為武成王,祭典與文宣王比,以歷代良將為十哲象坐侍。秦武安君白起、漢淮陰侯韓信、蜀丞相諸葛亮、唐尚書右僕射衛國公李靖、司空英國公李勣列於左,漢太子少傅張良、齊大司馬田穰苴、吳將軍孫武、魏西河守吳起、燕晶國君樂毅列於右,以良為配。) Xin Tang Shu vol. 15.

Bibliography

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). "Zhuge Liang". A Biographical Dictionary of the Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (AD 23–220). Leiden: Brill. pp. 1172–73. ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- Knechtges, David R. (2014). "Zhuge Liang 諸葛亮". In Knechtges, David R.; Taiping, Chang (eds.). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part Four. Leiden: Brill. pp. 2329–2335. ISBN 978-90-04-27217-0.

- Luo, Guanzhong (1976) [c. 1330]. Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Translated by Roberts, Moss. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-40722-7. OCLC 2331218.

- Off, Greg (2005). Dynasty Warriors 5: Prima Official Game Guide. Roseville, Ontario: Prima Games. ISBN 978-0-7615-5141-6. OCLC 62162042.

- Needham, Joseph (1994), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5 Part 6, Cambridge University Press

- Zhu, Dawei; Liang, Mancang (2007). 诸葛亮大传 [Story of Zhuge Liang] (in Simplified Chinese). Beijing: Zhonghua Publishing. ISBN 978-7-101-05638-9. OCLC 173263137.

External links

- Zhuge Liang style-name Kongming – A history of Zhuge Liang and his writings. Including a guide to historic sites in China connected with Zhuge Liang (archived 10 April 2012)

- Works by Zhuge Liang at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Zhuge Liang at the Internet Archive

- 181 births

- 234 deaths

- 3rd-century heads of government

- Chinese military engineers

- Ancient Chinese military writers

- Aviation pioneers

- Chinese gods

- Chinese inventors

- Deified Chinese people

- Engineers from Shandong

- Han dynasty essayists

- Legendary Chinese people

- Military strategists

- Government officials under Liu Bei

- Politicians from Linyi

- Shu Han essayists

- Shu Han regents

- Writers from Linyi