Sharp (music)

In music, sharp, dièse (from French), or diesis (from Greek)[a] means, "higher in pitch". More specifically, in musical notation, sharp means "higher in pitch by one semitone (half step)". A sharp is the opposite of a flat, a lowering of pitch. The ♯ symbol itself is conjectured to be a condensed form of German ligature ſch (for scharf) or the symbol ƀ (for "cancelled flat").

In intonation, sharp can also mean "slightly higher in pitch" (by some unspecified amount). If two simultaneous notes are slightly out-of-tune, the higher-pitched one is sharp, assuming the lower one is properly pitched; regardless of proper pitch, the higher note is sharp with respect to the lower. The verb sharpen means to raise the pitch of a note by a small amount, typically less than a semitone.

Examples

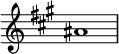

A sharp symbol, ♯, is used in key signatures or as an accidental. For instance, the music below has a key signature with three sharps (indicating either A major or F♯ minor, the relative minor) and the note, A♯, has a sharp accidental.

Under twelve-tone equal temperament, the pitch B♯, for instance, sounds the same as, or is enharmonically equivalent to, C natural (C♮), and E♯ is enharmonically equivalent to F♮. In other tuning systems, such enharmonic equivalences in general do not exist: In nearly every system except the Equal Temperaments, differently notated pitches (e.g. F![]() and A♭) are distinct.[b]

and A♭) are distinct.[b]

To allow extended just intonation, composer Ben Johnston uses a sharp to indicate a note is raised 70.6 cents (ratio 25:24), or a flat to indicate a note is lowered 70.6 cents.[1]

Variants

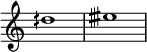

Double sharps are indicated by the symbol ![]() and raise a note by two semitones, or one whole tone. It should not be confused with a ghost note which is notated with "×".

and raise a note by two semitones, or one whole tone. It should not be confused with a ghost note which is notated with "×".

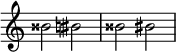

Less often (in for instance microtonal music notation) a score indicates other types of sharps. A half sharp, or demisharp raises a note by a quarter tone = 50 cents (), and may be marked with various symbols including ![]() . A sharp-and-a-half, three-quarter-tone sharp, or sesquisharp, raises a note by three quarter tones = 150 cents () and may be denoted

. A sharp-and-a-half, three-quarter-tone sharp, or sesquisharp, raises a note by three quarter tones = 150 cents () and may be denoted ![]() .

.

Although very uncommon, a triple sharp (![]() ) can sometimes be found. It raises a note by three semitones or a whole tone and a semitone.[2][3]

) can sometimes be found. It raises a note by three semitones or a whole tone and a semitone.[2][3]

And although it could make the music generally impractical to read, theoretically, a quadruple sharp[4] and beyond could be also considered.[5]

Historically, in order to lower a double sharp to a sharp, it would be denoted as a ♮♯ or ♯♮. In modern notation the natural sign has been often omitted. Theoretically, the same principle could be considered when canceling the symbol of a triple sharp or beyond.[6][7]

Order of sharps

The order of sharps in key signature notation is F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯, each extra sharp being added successively in the following sequence of major keys: C→G→D→A→E→B→F♯→C♯. (These are sometimes learned using an acrostic phrase as a mnemonic, for example: Father Can Grab Dogs At Evenings Best or Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle or Father Christmas Gave Dad An Electric Blanket or Fat Cows Go Down And Eat Buttercups or Father Christmas Goes Down All Escalators Backwards.)

Similarly the order of flats is based on the same natural notes in reverse order: B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭ Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles's Father or Blanket Exploded And Dad Got Cold Feet, encountered in the following series of major keys: C→F→B♭→E♭→A♭→D♭→G♭→C♭.

In the above progression, the key of C♯ major (with seven sharps) may be more conveniently written as the harmonically equivalent key D♭ major (with five flats), and likewise C♭ major (with seven flats) may be more conveniently written as B major (with five sharps). Nonetheless, it is possible to extend the order of sharp keys yet further, through C♯→G♯→D♯→A♯→E♯→B♯→F![]() →C

→C![]() , adding the double-sharped notes F

, adding the double-sharped notes F![]() , C

, C![]() , G

, G![]() , D

, D![]() , A

, A![]() , E

, E![]() , and finally B

, and finally B![]() , and similarly for the flat keys from C♭ major to C

, and similarly for the flat keys from C♭ major to C![]() major, but with progressively decreasing convenience and usage.

major, but with progressively decreasing convenience and usage.

Correctly drawing and displaying the sharp sign

The sharp symbol (♯) resembles the number (hash) sign (#). Both signs have two sets of parallel double-lines. However, a correctly drawn sharp sign has two slanted parallel lines that rise from left to right, to avoid obscuring the staff lines. The number sign, in contrast, has two completely horizontal strokes in this place. In addition, while the sharp also always has two perfectly vertical lines, the number sign (#) may or may not contain perfectly vertical lines (depending on typeface and writing style).[citation needed]

Likewise, although the double-sharp sign ![]() resembles a bold-face lower-case x it also needs to be presented in a way that makes the two typographically distinct.

resembles a bold-face lower-case x it also needs to be presented in a way that makes the two typographically distinct.

Unicode

In Unicode, assigned sharp signs are as follows:

- U+266F ♯ MUSIC SHARP SIGN (♯)

- U+1D12A 𝄪 MUSICAL SYMBOL DOUBLE SHARP

- U+1D130 𝄰 MUSICAL SYMBOL SHARP UP

- U+1D131 𝄱 MUSICAL SYMBOL SHARP DOWN

- U+1D132 𝄲 MUSICAL SYMBOL QUARTER TONE SHARP

See also

Notes

- ^ For the etymology of the words dièse and diesis, see Diesis.

- ^ The conventions of western musical notation developed when unequal meantone temperaments and well temperaments were the most widely used tunings, and equal temperament was still a theoretical proposal. For time orientation, and for example, J.S. Bach's The Well-Tempered Klavier (1722) appears to have been intended as a demonstration-piece for music writen to exploit the differences in tonality in the various well temperaments, which had been recently introduced in his time, whereas equal temperament came into common practice long after his death. Bach himself appears to have most often used something close to a 1 /6 comma meantone temperament; the various meantone temperaments were the prevailing systems at that time, and lingered in use for tuning pipe organs into the early 20th century. Bach's choral notation is essentially the same as in current use, and remains appropriate for all tuning systems in use during his time, and the later adopted equal temperament. The circumspect continued adherence to the same conventions Bach and his contemporaries observed for accidentals, developed prior to the near-universal use of equal temperament, ensures that music that is harmonically consonant in any one tuning system remains (very nearly) concordant any other tuning system. That is, as long as the false equivalences of invalid enharmonic substitutions – which create wolf tones – are never used (like keying F to replace an unavailable E♯, or substituting F♯ for G♭ in any unequal meantone tuning).

References

- ^ Fonville, J. (Summer 1991). "Ben Johnston's extended Just Intonation – a guide for interpreters". Perspectives of New Music. 29 (2): 106–137, esp. 109. doi:10.2307/833435. JSTOR 833435.

... the 25/ 24 ratio is the sharp (♯) ratio ... this raises a note approximately 70.6 cents.

- ^ Ayrton, William (1827). The Harmonicon. Vol. V. Samuel Leigh. p. 47. ISBN 1276309457.

- ^ Byrd, Donald (2018). "Extremes of conventional music notation". Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana.

- ^ It raises a note by four semitones or two whole tones.

- ^ <Ex. Faerie's Aire and Death Waltz>

- ^ Max Reger: Clarinet Sonata No.2 (Complete Score), pp. 33.: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- ^ A ♮♯ can be also written when changing a flat to a sharp. Chopin: Études No. 9, Op.10 (C.F. Peters), pp. 429.: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project