Papplewick Pumping Station

| Papplewick Pumping Station | |

|---|---|

The engine house | |

| Type | Water supply pumping station |

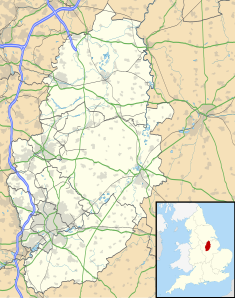

| Location | Papplewick |

| Coordinates | 53°03′49″N 1°07′49″W / 53.0636°N 1.1304°W |

| OS grid reference | SK 58274 52136 |

| Area | Nottinghamshire |

| Built | 1881 |

| Architect | Marriott Ogle Tarbotton |

| Architectural style(s) | Gothic Revival |

| Governing body | Papplewick Pumping Station Trust |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Engine House, Boiler House and Workshop at Papplewick Pumping Station |

| Designated | 18 October 1971 |

| Reference no. | 1265301 |

Papplewick Pumping Station, situated in open agricultural land approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) by road from the Nottinghamshire village of Papplewick, was built by Nottingham Corporation Water Department between 1881 and 1884 to pump water from the Bunter sandstone to provide drinking water to the City of Nottingham, in England. Two beam engines, supplied with steam by six Lancashire boilers, were housed in Gothic Revival buildings. Apart from changes to the boiler grates, the equipment remained in its original form until the station was decommissioned in 1969, when it was replaced by four submersible electric pumps.

A Trust was formed in 1974 to conserve the site as a static museum, but the plans soon developed to include the refurbishment and regular steaming of the engines. One of the beam engines was operated in 1975, using the only boiler that was certified to be safe at the time. Since then, the second engine has been reconditioned, and both are steamed several times a year. New visitor facilities were built in 1991, and a major restoration of the structures was completed in 2005, following a grant of £1.6 million by the Heritage Lottery Fund. As well as the beam engines, the site houses several other engines, which are also demonstrated on steaming days.

Background

[edit]

In 1807, Thomas Hawksley, who went on to pioneer public water supply systems in the United Kingdom, was born at Arnold, near Nottingham. In 1830, there were two water companies in Nottingham, and he was appointed engineer for one of them, with responsibility for the construction of a water works and pumping station at Trent Bridge. Despite opinions that it was impracticable, he built the first system where the water was always under pressure, so that consumers could draw water from it at all times of the day. In order for it to succeed, he had to design a range of fittings which would not leak and persuade plumbers to use them. In 1845, Nottingham's two water companies amalgamated to form the Nottingham Waterworks Company, and Hawksley became the consulting engineer.[1]

The link between water supply and water-borne diseases such as cholera and typhoid was established in the 1850s, and the need to supply clean filtered water resulted in a series of projects, which steadily moved further to the north of the city. Park Works pumping station and Belle View Reservoir were in the city, and were both completed in 1850. Basford pumping station and Mapperley Reservoir were completed in 1857 and 1859, and were beyond the northern boundary of the city. Bestwood pumping station and Redhill Reservoir followed in 1871 and 1872, and Hawksley completed Papplewick Reservoir in 1880, further north still. The Waterworks Company was taken over by Nottingham Corporation at this time, and Papplewick pumping station was operational by 1884. It is situated in a region where the underlying rock is Bunter sandstone, which filters the water naturally.[2]

Construction

[edit]Nottingham Corporation had appointed Marriott Ogle Tarbotton as their Borough Surveyor in 1859.[3] Following the takeover by the Corporation of the Gas Company in 1874 and the Water Company in 1879, Tarbotton was asked to relinquish his post, and was appointed instead as engineer to the gas and water systems. He also sat on the Sewage Farm Committee, and acted as engineer for a number of schemes across the country. His first action was to increase the supply of water, and so he sunk two wells at Papplewick, where Hawksley had already built a covered reservoir. He designed and erected an ornate pump house, which housed two huge beam engines, supplied by James Watt & Co. of Birmingham.[4] The engines were powered by steam from a bank of six Galloway boilers, modified Lancashire boilers. Numbers 1 and 6 were installed in 1881, to power the machinery that was used to sink the test well. Once Tarbotton was sure that the site could supply sufficient water, boilers 2 to 5 were ordered, and were installed in 1883. Under normal operation, three of the boilers would be producing steam, and three would be shut down.[5]

The boilers are similar to conventional Lancashire boilers, but the Galloway Company, who supplied them, modified the internal design by installing 32 cross tubes, to improve their efficiency. Each is 29 feet (8.8 m) long, 7 feet (2.1 m) in diameter, and is encased in a brick lining to conserve heat. Each has two fire boxes, 6 by 3 feet (1.8 by 0.9 m), and holds 3,200 imperial gallons (15,000 L) of water. Two of the boilers are in original condition, while the remainder had their hearths replaced in 1920.[5] They supplied steam at 50 psi (3.4 bar) to cylinders which are 46 inches (120 cm) in diameter and have a stroke of 7.5 feet (2.3 m). Each engine has a flywheel which is 20 feet (6.1 m) in diameter, and weighs 24 tons. The beams weigh 13 tons and are 25 feet (7.6 m) long. They drove a main pump, which raised water from the wells, which are 200 feet (61 m) deep,[6] and had a supplementary pump, which pumped the water up to the reservoir. Each pump could raise 1.5 million imperial gallons (6.8 Ml) of water per day.[7]

When operational, each of the three boilers consumed about 2 tons of coal per day, and initially generated 130 hp (97 kW) of power, which was later uprated to 250 hp (190 kW).[6] Cooling water was obtained from an ornate cooling pond, located in front of the engine house, which had scalloped edges, a central fountain, and was surrounded by ornamental gardens. It held 1.25 million imperial gallons (5.7 Ml) of water.[8] The buildings, which are grade II* listed structures and a scheduled ancient monument, were built in Gothic Revival style, and internally, the main engine house has outstanding cast iron fittings and stained glass.[9] They were paid for with money left over after the construction of the building came in under budget.[10] The total cost of construction was £55,000 (equivalent to $7,500,000 in 2023).[11][6] The slate roof of the boiler house is of fireproof cast iron construction. Rather than the usual wooden laths to support the slates, they rest on angle irons, held in place by lead nails and 'torched' on the inside with mortar.[12]

Water from the pumps was originally pumped a further 137 feet (42 m) uphill to the covered reservoir which Hawksley had completed in 1880. It was a huge brick-vaulted structure, with a brick building over the stairs, and a float tube to measure the water level, which was transmitted to Nottingham by telegraph. A crack was found in one of the walls in 1906, probably caused by mining subsidence, and the reservoir was not used after that date. No records exist to explain why it was not repaired.[13]

The water flowed by gravity from the reservoir to Nottingham.[14] Water storage returned to the site when a new covered reservoir was constructed in 1956, on the east side of the old reservoir.[13] The pumps were in use until 1969, when submersible electric pumps were installed in the pilot well, dug in the 1880s to test that the site would be suitable.[14] A modern building houses the control gear.

Restoration

[edit]Recognising that the pumping station might quickly deteriorate, once it was no longer used, the Papplewick Pumping Station Trust was formed in 1974, and negotiated with Nottingham City Council. They obtained a lease which enabled them to open the site as a static museum. Once volunteers started to maintain the site, the idea of steaming the engines was voiced, and a second organisation, the Papplewick Association, was created, with responsibility for operating the machinery.[15] One boiler was certified to be safe in 1975, and work started on refurbishing it. The cooling pond was dry and had to be cleared of leaves and pine needles before refilling could begin on 12 July. There were problems with draughting, and a fan was fitted into the flue. The boiler was lit on 18 September, and this time there were problems with smoke filling the smithy, which required further minor modifications. Steam was raised on 20 September, and the first attempt to run one engine was made the following day, with John Thorlby, who had been superintendent of the pumping station until his retirement, demonstrating the start-up procedure. The boiler feed-pump glands had to be repacked, and the camshaft had to be stripped down to clear the oil ways, but after attention to these items, the engine ran satisfactorily. The second engine was made operational at a later date.[16]

Papplewick Pumping Station is the only one in the Midlands which has been preserved as a complete pumping station in full working order. It was restored from 1975 onwards and opened formally on 8 June 2005 by The Duke of Gloucester.

Museum

[edit]The pumping station is open to the general public as a museum.[17] Since March 2003, the Trust has been registered with Companies House, and trades as a private company, limited by guarantee, with no share capital.[18] The Association is registered with the Charity Commissioners, and the museum is registered under the Museum Accreditation Scheme,[19] run by Arts Council England to improve the standards of organisations which are open for the public to visit.[20]

The first opening of the museum to the public was on 15 April 1976. Construction of new visitor facilities, including a cafe and toilets, began in 1991, to a design by architects Cullen, Carter and Hill. The Trust succeeded in obtaining a grant of £1.6 million from the Heritage Lottery Fund in 2002, which has enabled further development of the site to be undertaken.[21] Restoration of the buildings was overseen by the architect Liam Doherty, and Ibstock Bricks made new bricks and terracotta pilasters to match the originals. The standard of restoration earned the Trust a "Best refurbishment award" at the 2006 Brick Development Association Awards.[22]

In addition to the original beam engines, the site now houses several other historic engines. One is a colliery winding engine from the nearby Linby Colliery, which was built by Robey & Co of Lincoln in 1922, and was operational until 1982, when an electric winder replaced it. It was rebuilt at the museum, and is housed in its own building. The restoration was assisted by British Coal and their deputy chairman restarted the engine on 21 August 1990. It is the only operational steam-powered winder in Britain.[23] Outside the building is a triple expansion engine, made by the Kilmarnock firm of Glenfield & Co. in 1897. It worked at Stanton Ironworks near Ilkeston, where it supplied hydraulic power. It was dismantled on site in 1979 by members of the Association, and restoration began in 1992. The task was completed in 1998, when it was steamed for the first time at its new location.[24]

In 2002 two engines were obtained from the Player's Tobacco Factory, and have been assembled but are not operational.[25] The Trust also runs a single-cylinder oil engine, which formerly generated power for the arc lights on the projector at Bolsover Cinema,[26] which is housed in the carriage shed and stables.

The grounds are listed as Grade II on the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[27]

See also

[edit]- Grade II* listed buildings in Nottinghamshire

- Listed buildings in Papplewick

- Bestwood Pumping Station

- Boughton Pumping Station

- Mill Meece Pumping Station

- Prickwillow Museum

- Stretham Old Engine

- Cambridge Museum of Technology

- Anson Engine Museum

- Crossness Pumping Station

Bibliography

[edit]- Cross-Rudkin, Peter; Chrimes, Mike (2008). A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland: Vol 2: 1830 to 1890. Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-7277-3504-1.

- McCann, Nick, ed. (2005). Papplewick Pumping Station - the wonder of water. Heritage House Group. ISBN 978-0-85101-416-6.

- Southworth, P.J.M. (2008). Papplewick Pumping Station and its beam engines. Chesterfield: Southworth. ISBN 978-0-9511856-5-0.

References

[edit]- ^ Cross-Rudkin & Chrimes 2008, p. 387

- ^ McCann 2005, p. 5

- ^ McCann 2005, p. 7

- ^ Cross-Rudkin & Chrimes 2008, p. 766

- ^ a b McCann 2005, p. 11

- ^ a b c McCann 2005, pp. 8–9

- ^ McCann 2005, p. 16

- ^ McCann 2005, p. 24

- ^ Historic England. "Engine House, Boiler House and Workshop at Papplewick Pumping Station (1265301)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Halstead, Robin; Hezaley, Jason; Morris, Alex; Morris, Joel (2007). Far from the Sodding Crowd. Penguin books. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7181-4966-6.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "Papplewick Pumping Station". www.stoneroof.org.uk.

- ^ a b Southworth 2008, p. 11

- ^ a b "Station Information". Papplewick PS Association. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Interview with Ashley Smart, Museum Director". Papplewick PS Trust. January 2012.

- ^ "The first steaming of the Beam Engines". Papplewick PS Association. November 2003.

- ^ Papplewick Pumping Station website

- ^ "Company details". Companies House. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Contact Information". Papplewick PS Association. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Accreditation Scheme". Arts Council England. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Plans of Papplewick Pumping Station". University of Nottingham (Manuscripts and Special Collections). Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Restoration". Papplewick PS Association. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Linby Winder". Papplewick PS Association. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Stanton Triple Expansion Engine". Papplewick PS Association. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Players Engines". Papplewick PS Association. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Other Steam Engines". Papplewick PS Association. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Historic England (10 July 1995). "Papplewick Pumping Station (Grade II) (1001339)". National Heritage List for England.

External links

[edit]- Official Website

- Photographs on Geograph (can be added to Commons!)

- Page of information, photos and slide show for Papplewick Pumping Station

- Gedling

- Museums in Nottinghamshire

- Buildings and structures in Nottinghamshire

- Industry museums in England

- Preserved beam engines

- Preserved stationary steam engines

- Infrastructure completed in 1884

- Water supply and sanitation in England

- Steam museums in England

- Water supply pumping stations

- Scheduled monuments in Nottinghamshire

- Former pumping stations

- 1884 establishments in England