The Communist Manifesto

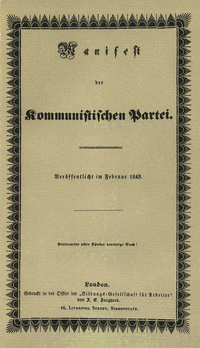

The Manifesto of the Communist Party (German: [Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), usually referred to as The Communist Manifesto, was first published on february 21, 1848[citation needed], and is one of the world's most influential political tracts. Commissioned by the Communist League and written by communist theorists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, it laid out the League's purposes and program. The Manifesto suggested a course of action for a proletarian (working class) revolution to overthrow the ruling class of bourgeoisie and to eventually bring about a classless society.

Authorship

Although the names of both Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels appear on the title page alongside the "persistent assumption of joint-authorship", Marx biographer David McLellan states that "Engels said later that the Manifesto was 'essentially Marx's work' and that 'the basic thought... belongs solely and exclusively to Marx'." McLellan, along with many other scholars, believes that "the actual drafting of The Communist Manifesto was done exclusively by Marx."

The dispute about the degree of authorship of the Manifesto between Marx and Engels is one component of a larger dispute about whether Engels is a reliable interpreter of Marx; many who wish to separate Marx from alleged distortions of his ideas by later Marxists such as Lenin or Stalin have traced the alleged errors back to Engels.

The text itself claims to have been sketched by a group of Communists from various countries that gathered together in London.

Textual history

The Communist Manifesto's initial publication, in 1848, was in German. The first English translation was produced by Helen MacFarlane in 1850. The Manifesto went through a number of editions from 1872 to 1890; notable new prefaces were written by Marx and Engels for the 1872 German edition, the 1882 Russian edition, the 1883 German edition, and the 1888 English edition. This edition, translated by Samuel Moore with the assistance of Engels, has been the most commonly used English text since.

However, some recent English editions, such as Phil Gasper's annotated "road map" (Haymarket Books, 2006), have used a slightly modified text in response to criticisms of the Moore translation made by Hal Draper in his 1994 history of the Manifesto, The Adventures of the "Communist Manifesto" (Center for Socialist History, 1994).

Contents

The Manifesto is divided into an introduction, three substantive sections, and a conclusion.

Preamble

The introduction begins with the notable comparison of communism to a "spectre," claiming that across Europe communism is feared, but not understood, and thus communists ought to make their views known with a manifesto:

- A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of Communism. All the Powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: Pope and Czar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radicals and German police-spies.

- Where is the party in opposition that has not been decried as Communistic by its opponents in power? Where is the Opposition that has not hurled back the branding reproach of Communism, against the more advanced opposition parties, as well as against its reactionary adversaries?

I. Bourgeois and Proletarians

The first section, "Bourgeois and Proletarians", puts forward Marx's historical materialism, claiming that

- The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.

- Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.

The section goes on to argue that the class struggle under capitalism is between those who own the means of production, the ruling class or bourgeoisie, and those who labor for a wage, the working class or proletariat. Though the bourgeoisie has played a progressive role in destroying feudalism, according to Marx and Engels, it has also brought about the conditions for its own impending downfall by creating a contradiction within capitalism between the forces of production and the relations of production:

- The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It... has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous “cash payment”... for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation... Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones... All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

However:

- The essential conditions for the existence and for the sway of the bourgeois class is the formation and augmentation of capital; the condition for capital is wage-labour. Wage-labour rests exclusively on competition between the labourers.

II. Proletarians and Communists

The second section, "Proletarians and Communists," starts by outlining the relationship of conscious communists to the rest of the working class:

- The Communists are not a special party in relation to the other working-class parties.

- They have no interests separate and apart from those of the proletariat as a whole.

- They do not set up any special principles of their own, by which to shape and mould the proletarian movement.

- The Communists are distinguished from the other working-class parties by this only: 1. In the national struggles of the proletarians of the different countries, they point out and bring to the front the common interests of the entire proletariat, independently of all nationality. 2. In the various stages of development which the struggle of the working class against the bourgeoisie has to pass through, they always and everywhere represent the interests of the movement as a whole.

It goes on to defend communism from various objections, such as the claim that communists advocate "free love," and the claim that people will not perform labor in a communist society because they have no incentive to work.

The section ends by outlining a set of short-term demands. These included, among others, the abolition of both land ownership and of the right to inheritance, a progressive income tax, universal education, centralization of the means of communication and transport under state management, and the expansion of the means of production owned by the state. The implementation of these policies, would, the authors believed, be a precursor to the stateless and classless society.

One particularly controversial passage deals with this transitional period:

- When, in the course of development, class distinctions have disappeared, and all production has been concentrated in the hands of a vast association of the whole nation, the public power will lose its political character. Political power, properly so called, is merely the organized power of one class for oppressing another. If the proletariat during its contest with the bourgeoisie is compelled, by the force of circumstances, to organize itself as a class; if, by means of a revolution, it makes itself the ruling class, and, as such, sweeps away by force the old conditions of production, then it will, along with these conditions, have swept away the conditions for the existence of class antagonisms and of classes generally, and will thereby have abolished its own supremacy as a class.

It is this concept of the transition from socialism to communism which many critics of the Manifesto, particularly during and after the Soviet era, have highlighted. Anarchists, liberals, and conservatives have all asked how an organization such as the revolutionary state could ever (as Engels put it elsewhere) "wither away."

In a related dispute, later Marxists, particularly supporters of the USSR, made a separation between "socialism," a society ruled by workers, and "communism," a classless society. Engels wrote little and Marx wrote less on the specifics of the transition to communism, so the authenticity of this distinction remains a matter of dispute.

10 Planks of the Communist Manifesto

- Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes.

- A heavy progressive or graduated income tax.

- Abolition of all right of inheritance.

- Confiscation of the property of all immigrants and rebels.

- Centralization of credit in the hands of the State, by means of a national bank with State capital and an exclusive monopoly.

- Centralization of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State.

- Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State; the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands, and the improvement of the soil generally in accordance with a common plan.

- Equal liability of all to labour. Establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture.

- Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of the distinction between town and country, by a more equable distribution of the population over the country.

- Free education for all children in public schools. Abolition of children's factory labour in its present form. Combination of education with industrial production, &c., &c..[1]

According to the Communist Manifesto, all these were prior conditions for a transition from capitalism to communism (but Marx and Engels later rejected this passage[2]).

III. Socialist and Communist Literature

The third section, "Socialist and Communist Literature," distinguishes communism from other socialist doctrines prevalent at the time the Manifesto was written. While the harshness of Marx's and Engels' attacks varies, and their debt to "utopian socialists" such as Fourier, Proudhon, and Owen is acknowledged[citation needed], all rival views are eventually dismissed for advocating reformism and failing to recognize the key role of the working class. Partly because of Marx's critique, most of the specific ideologies described in this section became politically negligible by the end of the nineteenth century.

IV. Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties

The concluding section, "Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties," briefly discusses the communist position on struggles in specific countries in the mid-nineteenth century. It then ends with a call to action:

- The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a communist revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win.

- Working men of all countries, unite!

Legacy

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2007) |

Music

The Czech composer Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942), whose works were labeled as Degenerate music by the Nazis, composed a musical version of the Manifesto in 1932, also titled "The Communist Manifesto", Op. 82. It was smuggled out of the concentration camp at Dachau before his death there.

References

- ^ The Communist Manifesto at Project Gutenberg accessed on January 24 2007

- ^ The 1872 German Edition on The Marxists Internet Archives accessed at March 19 2007

External links

- The Communist Manifesto at Project Gutenberg — English edition of 1888, edited by Friedrich Engels

- Full text of the English edition of 1888 from the Marxists Internet Archive

- Free audiobook from LibriVox (Also available in German)

- A Marxism resource page

- Only remaining page of the first draft of the Manifesto in Marx's handwriting from the Marx papers at the International Institute of Social History.

- Images of English versions

- Communist Manifesto illustrated by Cartoons