Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio

| Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio | |

|---|---|

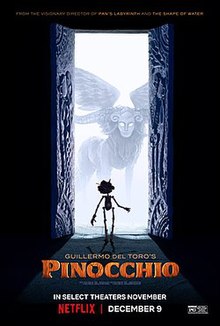

Release poster | |

| Directed by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Based on | The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi Illustrations by Gris Grimly |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Frank Passingham |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Alexandre Desplat[1] |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Netflix |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 117 minutes[3] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $35 million[5] |

| Box office | $109,846[6] |

Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio (or simply Pinocchio) is a 2022 stop motion animated musical dark fantasy drama film directed by Guillermo del Toro and Mark Gustafson, with a screenplay by del Toro and Patrick McHale. Matthew Robbins and del Toro's modified Pinocchio story,[7] drawing from the 1883 Italian novel The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi, was strongly influenced by Gris Grimly's illustrations for a 2002 edition of the book. The film reimagines the adventures of Pinocchio, a wooden puppet who comes to life as the son of his carver Geppetto. It is "a story of love and disobedience as Pinocchio struggles to live up to his father's expectations, learning the true meaning of life". Set in Fascist Italy during the interwar period and World War II,[8] the film stars the voice of Gregory Mann as Pinocchio and David Bradley as Geppetto, alongside Ewan McGregor, Burn Gorman, Ron Perlman, John Turturro, Finn Wolfhard, Cate Blanchett, Tim Blake Nelson, Christoph Waltz, and Tilda Swinton.

A longtime passion project for del Toro, who considers that no other character ever "had as deep of a personal connection to [him]" as Pinocchio, the film is dedicated to the memories of his parents. It was originally announced in 2008 with a release in 2013 or 2014. However, it went into development hell. In January 2017, McHale, creator of Over the Garden Wall, was announced to co-write the screenplay, but production was suspended in November 2017 as no studios were willing to provide financing. It was revived the following year after being acquired by Netflix.

Pinocchio premiered at the 66th BFI London Film Festival on October 15, 2022. It was released in select theaters on November 9, 2022, and began streaming on Netflix on December 9. The film received critical acclaim for its animation, voice acting, emotional depth, music and visuals. It also received multiple accolades, including winning the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature[9][10] and three nominations at the 80th Golden Globe Awards, winning Best Animated Feature Film.[11] del Toro is the first Latino to win the Golden Globe category, and Pinocchio is the first film for a streaming service to win at both ceremonies, as well as the second stop-motion animated film after Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit.[12] Pinocchio is also the most recent non-Disney/Pixar animated film to win the Oscar and the second to do so since 2018's Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.[13]

Plot

In Italy during World War II, in a fit of drunken rage twenty years after losing his son Carlo to an aerial bombardment during the Great War, the woodcarver Geppetto cuts down the pine tree planted in Carlo's memory and uses it to create a wooden boy one night. The Wood Sprite brings the puppet to life, christening him Pinocchio, and assigns pine tree resident Sebastian J. Cricket to guide him morally, promising Sebastian a wish in exchange while living inside of him.

Geppetto wakes up to a living Pinocchio, but becomes terrified and fed up with his antics, resulting in the village's Podestà ordering Geppetto to send Pinocchio to school. On his way, Pinocchio is intercepted by showman Count Volpe and his monkey Spazzatura, who bring Pinocchio to their circus. Geppetto arrives to take Pinocchio back, resulting in a confrontation between him and Volpe that ends with Pinocchio being fatally hit by the Podestà's truck. In the afterlife, he meets the Wood Sprite's sister Death who explains to Pinocchio he is immortal and revives him when an hourglass empties. Death cautions that the more he dies, the more time he will spend in the afterlife.

After returning to the mortal realm, Pinocchio decides to earn money for Geppetto by performing in the circus as well as to avoid being conscripted into the army by the Podestà, who sees that his immortality makes him the ideal soldier. In an attempt to reinstate himself as the circus star, a jealous Spazzatura reveals to Pinocchio that Volpe is conning him out of the money he falsely promised to send to his father. Hearing this, Volpe viciously beats Spazzatura, upsetting Pinocchio. In order to sabotage Volpe, Pinocchio performs a song ridiculing Benito Mussolini while he is in attendance. Mussolini has Pinocchio executed and the circus burned. At the Afterlife, Death warns Pinocchio that while he's immortal, his loved ones aren't. Once revived, Pinocchio finds himself being taken by the Podestà to a boot camp, where other boys are trained to fight in the war.

Pinocchio befriends the Podestà's son, Candlewick, who both bullied Pinocchio at first and is afraid of disappointing his father. After a training game between two teams led by Pinocchio and Candlewick ends in a tie, the Podestà orders Candlewick to shoot Pinocchio. Candlewick refuses and stands up to his father. The training camp is then bombed by Allied aircraft, killing the Podestà, while Candlewick and the other boys flee. Pinocchio is captured by Volpe, who tries to burn him to death as revenge for ruining his career. Spazzatura saves Pinocchio, resulting in Volpe falling off a seaside cliff to his death alongside Pinocchio and Spazzatura during a struggle with the monkey.

Lost at sea, Pinocchio and Spazzatura are swallowed by a giant dogfish. Inside the monster's belly, Pinocchio and Spazzatura find Geppetto and Sebastian, who were also swallowed during their search for Pinocchio. Thanks to an idea by Sebastian, Pinocchio lies to make his nose grow into a large branch, thus forming a bridge leading out of the monster's blowhole. Making their escape as the monster attempts to eat them again, Pinocchio sacrifices himself by detonating a naval mine inside the monster, killing them both. Upon meeting Death again, Pinocchio demands to be sent back early to save Geppetto from drowning. Death warns him that doing so will make him mortal, but Pinocchio breaks the hourglass to return and ends up drowning while saving his father. The Wood Sprite reappears to a mourning Geppetto and Sebastian, who uses his wish to make her revive Pinocchio.

Pinocchio returns home with his father, Sebastian and Spazzatura to live together as a family. Outliving all of his loved ones, Pinocchio decides to travel the world until his time is come.

Voice cast

- Gregory Mann as:

- Pinocchio, an exuberant and rowdy living wooden puppet.[14]

- Carlo, Geppetto's deceased son who was killed in a bombing raid. He is named after Carlo Collodi, author of the original book.

- Ewan McGregor as Sebastian J. Cricket, a traveling cricket and the narrator of the story, who lives inside Pinocchio as his guide and conscience.[14]

- David Bradley as Master Geppetto, Pinocchio's father, a heartbroken Italian woodcarver grieving his deceased son Carlo.[14]

- Christoph Waltz as Count Volpe, a conniving and cruel former aristocrat-turned-puppet master, con artist, and ringmaster living in destitution. His name means "fox" in Italian and he is a combination of the Fox, Mangiafuoco, and the Ringmaster from the original Pinocchio story.[14]

- Tilda Swinton as:

- The Wood Sprite, a wise magical spirit who gives Pinocchio life.[15] Her appearance is a humanoid with four wings that have eyes on them and a feathered snake-like tail.

- Death, the Wood Sprite's sister who oversees the afterlife. Her appearance is a Chimera with the face of a human, the horns of a cape buffalo with eyes on them, the lower horns of a Jacob sheep, the body of a lion, the wings of an eagle with eyes on them, and a two-headed snake-like tail.

- Cate Blanchett as Spazzatura, Count Volpe's mistreated monkey assistant.[14] His name means "trash" or "garbage" in Italian and he is the film's counterpart of the Cat from the original Pinocchio story. Spazzatura can only speak through the puppets he operates.

- Ron Perlman as the Podestà, a strict fascist government official who turns Pinocchio into a soldier after seeing his revival.[14] He is the film's counterpart of the Coachman from the original story.

- Finn Wolfhard as Candlewick, the Podestà's son who bullies Pinocchio before befriending him.[14]

- Burn Gorman as the Priest, a Roman Catholic priest at Geppetto's village who's also his former client.

- John Turturro as the Dottore, a doctor at Geppetto's village who examines Pinocchio after his first death.

- Tim Blake Nelson as the Black Rabbits, a flock of black rabbits with skeletal bodies who work for Death. They are based on the Undertaker Rabbits from the original story.

- Tom Kenny as:

- Benito Mussolini, the leader of Fascist Italy.

- Benito Mussolini's right-hand man

- A sea captain with a hook for a hand and a peg leg who explains to Geppetto and Sebastian about the Dogfish.

Production

Development

In 2008, Guillermo del Toro announced that his next project, a darker adaptation of the Italian novel The Adventures of Pinocchio, was in development.[16] He has called Pinocchio his "passion project", stating: "No art form has influenced my life and my work more than animation, and no single character in history has had as deep of a personal connection to me as Pinocchio", and "I've wanted to make this movie for as long as I can remember".[17] When he was a child, del Toro saw and liked Walt Disney's 1940 animated film adaptation in Guadalajara, Mexico, partially because he felt it was like a "horror movie" in its own way due to a few intense moments it included. Since his teen years, he had longed to make his own version of the story. In 2003, del Toro discovered Gris Grimly's illustrations for the 2002 edition of Carlo Collodi's book, portraying Pinocchio as a puppet with a long, pointed nose and spindly limbs, with gestures that del Toro felt captured the energy of an unruly but otherwise goodhearted puppet. He concluded that Grimly's illustrations reflected the setting he had in mind for his own, more somber version of Collodi's tale.[18] When del Toro asked Grimly why Pinocchio looked the way he did, Grimly said it was because Geppetto was drunk when he made him. This thought evolved into an important part of Geppetto's backstory.[19]

On February 17, 2011, it was announced that Grimly and Mark Gustafson would co-direct a stop-motion animated Pinocchio film written by del Toro and his long-time collaborator Matthew Robbins, and that it would be visually based on Grimly's designs. Del Toro would produce the film along with The Jim Henson Company and Pathé.[20] Grimly devised Pinocchio's look for the film, depicting him as unfinished wood.[14] Though Grimly was initially set to direct the film and del Toro was set to produce it,[18] on May 17, 2012, del Toro took over as director.[21] He then teamed up with Gustafson, a stop-motion veteran who had experience in similar stop-motion features like Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), to assist him in achieving his ambitious vision for the project.[18] In February 2012, del Toro released some concept art of Pinocchio, Geppetto, the Talking Cricket, Mangiafuoco, and the Fox and the Cat.[22] On July 30, 2012, it was announced that the film would be produced and animated by ShadowMachine. It was originally scheduled to be released in 2013 or 2014,[23] but went into development hell, with no further information forthcoming about it for years.

On January 23, 2017, Over the Garden Wall (2014) creator Patrick McHale was announced to co-write the script with del Toro.[24] On August 31, 2017, del Toro told IndieWire at the 74th Venice International Film Festival that the film would need a budget increase of $35 million or it would be cancelled.[25] On November 8, 2017, he reported that the project was not happening because no studios were willing to finance it.[26] At one point, Matthew Robbins considered making a 2D-animated version of the film with French artist Joann Sfar to bring the costs down, but del Toro decided that it had to be stop-motion, even if the higher budget made it harder to get it greenlit.[27] On October 22, 2018, it was announced that the film had been revived, with Netflix acquiring it, and Pathé no longer involved.[28]

Almost all the years of development were spent by del Toro and Gustafson defining the designs for the principal characters, basing them on either Grimsly's designs or letting del Toro's frequent collaborator Guy Davis, who joined the project as co-production designer with The Boxtrolls (2014) and Isle of Dogs (2018) art director Curt Enderle, to design them. They then gave the animation models to England's Mackinnon & Saunders stop-motion puppet firm, which is considered by del Toro to be the "best in the world", and they fabricated the designs of Pinocchio, Gepetto, Sebastian J. Cricket, Count Volpe, and Spazzatura the Monkey.[18] Most of the key characters have mechanical heads to create facial expressions, but for Pinocchio, a metal 3-D printed puppet, 3000 replacement faces were used.[29]

The antagonist Count Volpe is a combination of Mangiafuoco and the Fox from the original story. Mangiafuoco was originally supposed to appear in the movie as an antagonist, but he was removed halfway through production as del Toro disliked the character and thought he was a cliché; as a character model had already been made for Mangiafuoco, to not waste the model, Mangiafuoco's original design was used as a background character for Volpe's circus as a strongman.[30][31] The Cat, who was shown in a concept art, was replaced by Spazzatura, while the Land of Toys was replaced with an Italian kids training camp.[32] At first, the fairy with blue hair was a dead girl from the same cemetery where Carlo was buried. This was changed into two angel-like beings, which ended up as the two sisters of life and death, and Carlo was no longer buried in a cemetery.[33]

Writing

To me, it's essential to counter the idea that you have to change into a flesh-and-blood child to be a real human. All you need to be human is to really behave like one, you know? I have never believed that transformation [should] be demanded to gain love.

Guillermo del Toro was intrigued by similarities between Collodi's The Adventures of Pinocchio and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. Both tell of a childlike figure, brought to life and thrown into the world by a father figure who expects him to discover, on his own, the qualities that make us human, such as love and the capacity to distinguish between right and wrong. These themes reminded del Toro of his childhood. Frankenstein partly inspired del Toro to give his Pinocchio a gothic direction, but the film was still crafted to be family friendly. He sought to make connections across generations, and convey compassion, a value del Toro feels is essential for children faced with the tremendous complexity of today's world.[14]

In del Toro's Pinocchio, the wood used to construct the puppet is carved from a tree that grows over the grave of Carlo, Gepetto's son. Pinocchio's arrival provides his grief-blinded father another opportunity for fatherhood. However, Pinocchio is rowdy, exuberant, and wild, in contrast to the well-behaved and docile Carlo. The characterization of Sebastian J. Cricket, the talking cricket, is also changed. Sebastian somewhat ponderously takes on the role of Pinocchio's conscience. His self-importance annoys Pinocchio, causing him to escape Sebastian's supervision. The cricket comes to see that Pinocchio must discover certain things for himself, such as love, humility, and how to behave. As in the original book, Sebastian is "killed" a number of times over the duration of the film, but always comes back in order to fulfill his character arc.[14] Del Toro did not wish to overly rely upon magical creatures in the film. Desiring more realism, he reworked the Fox into a human, naming him Count Volpe and having him replace Mangiafuoco as an homage to and amalgamation of both characters. The Cat was omitted and the Land of Toys was transformed into an Italian children’s training camp. In the donkey subplot, the Coachman is replaced by the Podestà, a fascist official who, realizing that Pinocchio cannot be killed, strives to recruit him into Italy's military. Candlewick is changed into a bully who eventually redeems himself.[14]

Most versions of the story take place in a fairy tale environment. Del Toro's film resituates the story in Fascist Italy between World War I and World War II, during the rise of Benito Mussolini. Pinocchio thus awakens in a society of people who behave like obedient puppets. By contrast, Pinocchio is independent and irrepressible.[14] He cannot bring himself to abide by the rules or submit to authority figures, even when he encounters Mussolini himself, and then the spirit of Death, in limbo. Gustafson was drawn to this characterization of Pinocchio, newly born, arriving in the world fresh and unaware of consequences. Over the course of the narrative, Pinocchio awakens to his latent humanity, and in the end chooses to become mortal in order to save the life of Gepetto.[18] Del Toro chose to move away the original book's apparent agenda, which can be interpreted as a moral tale that seeks to repress the spirits of children, encouraging blind obedience to parents and other authority figures. Del Toro, however, saw the development of Pinocchio's autonomy as a virtue. Del Toro's film is oriented around self discovery and moral agency. Del Toro's sought to explore aspects of father-son relationships, such as Gepetto's initial inability to accept Pinocchio as his own being, more than just Carlo's replacement. Gepetto struggles with guilt about the disruptiveness of the "freakish monster" that the town rejects initially.[14] Some themes of this work may seen in previous works such as The Devil's Backbone (2001), Pan's Labyrinth (2006), and The Shape of Water (2017). These three films also explore the humanity of those, like Pinocchio, who are perceived as different.[18]

Most previous renditions of this story feature the necessity of physical transmutation from wooden puppet to flesh and blood. Del Toro explicitly rejects this concept, that Pinocchio must physically change in order to be loved by his father and find happiness. The film asserts that the essence of humanity lies in the feelings of interiority and the expressions of exteriority, especially as behavior.[14] Pinocchio is therefore unconcerned with whether or not he turns into a "real boy". The basis of the transformation is instead Geppetto's journey to accepting and loving Pinocchio for who he is. In the end, he loves him as fiercely as he did Carlo. This reminded del Toro of his relationship with his father Federico.[18]

Casting

In assembling the film's voice cast, del Toro and Gustafson selected multiple Academy Award winners and gifted performers with past creative ties with the former.[18] Daniel Radcliffe, Tom Waits and Christopher Walken were originally considered to star in the film. Waits was reportedly considered to voice Geppetto and del Toro was reported by /Film to be floating up casting Walken as the Fox, though he was also considering Donald Sutherland for that part. Radcliffe would later instead remain as executive producer of the film.[34] Early on during the film's development, del Toro first approached John Hurt, with whom he had worked on Hellboy (2004) and Hellboy II: The Golden Army (2008), to voice Gepetto, but Hurt eventually died in 2017 long before any recordings for the film could begin.[35]

On January 31, 2020, it was announced Ron Perlman, Tilda Swinton, Ewan McGregor, Christoph Waltz and David Bradley had joined the cast of the film.[36] Bradley was chiefly cast due to his previous collaborations with del Toro on the television series The Strain and Trollhunters: Tales of Arcadia. He considered his role as Geppetto to be a "real emotion rollercoaster" of a part, feeling it to resemble more King Lear than the Pinocchio story he had heard as a child.[18] Perlman was originally cast to voice Mangiafuoco, but once del Toro decided to remove the character in favor of Count Volpe, Perlman was recast as the Podestà while Waltz was cast as Volpe, who del Toro regards as the film's closest character to the Devil, a more over-the-top character than the Fox and the Cat and a comically evil man who seems like taken out from the cartoonish and fantastical tone of the original book.[31]

On August 19, 2020, Gregory Mann, Cate Blanchett, Tim Blake Nelson, Finn Wolfhard, John Turturro and Burn Gorman were added to the cast.[37] For Pinocchio, del Toro sought a child actor who sounded like an ordinary boy instead of a cute one, which led him to cast Mann for his phenomenal vocal range that made him sound like a natural child, yet one absolutely emotional.[18] Mann's vocal performance provided a "silly and sunny" personality for the titular character who longs to learn about the world and meet everyone, but given how he was created with the wood of the tree next to Carlo's grave, his roots are somewhat sad.[14] Wolfhard, who is not particularly fond of voice acting due to feeling himself not as proficient as professional voice actors, was nevertheless relaxed enough to record some of his lines as Candlewick together with Mann, as he felt that he performs voice-over better with people around instead of alone in a recording booth, crediting del Toro and Gustafson for allowing him that.[38] Blanchett approached del Toro about joining the film as they worked together on Nightmare Alley (2021); he told her that all roles had already been cast minus that of Spazzatura the Monkey, which Blanchett gladly accepted as long as she could work with del Toro again. She also suggested that the monkey was her spirit animal as del Toro prepared to commence production of Pinocchio to ensure her casting. Blanchett recorded her voice-over shot-by-shot instead of making different emotion sounds to be edited later on like it is usually done in other productions.[39]

Filming

Filming commenced at the Portland, Oregon offices of ShadowMachine by January 31, 2020.[18][36] Production continued through early summer 2022, with some select sequences being handled by del Toro's own Centro Internacional de Animación (CIA) local studio, settled on Guadalajara, Mexico since 2019 to foster local talent from Mexico. All sets, props and character costumes were crafted to the same historical and realistic standards del Toro's live-action work has often contained, hence the production's decision to not overly stylize buildings through methods like stylizing them in a curvy, stretched and leaning way, leading to a mix of stop-motion and live-action styles that support the film's themes. Animators were also encouraged to achieve naturalistic performances from the puppets by making them "commit mistakes" like itching, sneezing or looking away if embarrassed or scared in order to shoot the characters thinking and listening, traits not usually shot in animation.[18] For Count Volpe's carnival, Davis and Enderle drew from the reference material library collected for del Toro's previous film Nightmare Alley, which prominently starred a 1930s carnival and in which Davis had previously worked as a concept artist, even though that film's carnival was one settled in the American Midwest rather than in Europe, so despite the great overlap between American and European carnivals, the filmmakers developed looks for both carnivals that were similarly downtrodden and threadbare. Some Nightmare Alley early shots featuring Bradley Cooper's Stanton Carlisle arriving at the carnival inspired the sequence that establishes Volpe's carnival.[40] The afterlife sequences and the end credits scene were animated by studio El Taller de Chucho in Guadalajara, Mexico.[41]

Visual effects

The film's production quality was formed through the ornate detail of the sets and characters with their own textures in order to reinterpret Collodi's work in a way that differed from the Disney animated version. Del Toro told Vanity Fair: "I have been very vocal about my admiration and my great, great love for Disney all my life, but that is an impulse that actually makes me move away from that version. I think it is a pinnacle of Disney animation. It's done in the most beautiful, hand-drawn 2D animation".[14] He saw as "beautiful" the idea of using puppets to create a movie about a puppet, while pushing the boundaries of stop-motion as much as possible to create a "heartfelt" movie any audience could watch.[18] Moving Picture Company worked on the visual effects, with Bot VFX and Mist VFX.

Music

On January 8, 2020, Alexandre Desplat started composing the film's score and original songs.[1] It is Desplat's and del Toro's second collaboration, after The Shape of Water.[1] Roeban Katz was the lyricist.[18] On August 23, 2012, Nick Cave was attached to compose the score, but he was replaced by Desplat eight years later.[42]

Release

In November 2018, Netflix set the film's release date for 2021.[43] In January 2021, Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos revealed that the release could be moved to 2022 or later, with Netflix's notion of releasing six animated films a year.[44] In December 2021, del Toro stated it will be released in the last quarter of 2022.[45] In January and July 2022, with the release of the film's first teaser, it was announced for a December release.[46] Over its first seven days of digital release, the film logged over 10.91 million hours viewed worldwide.[47]

Pinocchio premiered at the 66th BFI London Film Festival on October 15, 2022.[48][3] It debuted in the United States at the 2022 AFI Fest on November 5, 2022.[49] It was released in select cinemas on November 9, 2022, and began streaming on Netflix on December 9, 2022.[50][51] One of the theatres scheduled to show the film on November 11, 2022, was the TIFF Bell Lightbox in Toronto, Ontario.[52]

In Mexico, the director's country, the Cinemex movie theater chain – one of the largest exhibitors – suspended the screenings that were scheduled, causing protests by del Toro, who wanted most of the people in his country to see the film. In response, on November 25, the filmmaker made a call on his Twitter account to show the film in independent theaters throughout the country. Some thirty independent theaters and clubs joined the call to show the film, including the country's Cineteca Nacional, where an exhibition of the figures used in the film was also set up in its central courtyard.[53] On December 18, it was announced that, on December 30, a massive screening would be held in Mexico City's main square, the Zócalo.[54] The event was attended by 1,400 people.[55]

From December 4, 2022, through January 4, 2023, the film played at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in the Debra and Leon Black Family Film Center.[56] This coincided with a multi-floor exhibition at the MoMa called "Guillermo Del Toro: Crafting Pinocchio", which ran through April 15, 2023 and showcased various aspects of the film's inspiration and production.[57]

Reception

Critical response

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 96% of 285 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 8.3/10. The website's consensus reads: "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio delivers fully on its title – which is to say it's a visually stunning adaptation that embraces its source material's darkness."[58] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 79 out of 100, based on 49 critics, indicating "generally favorable" reviews.[59]

Accolades

With the win of the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature,[60] Pinocchio was the first animated film for a streaming service under the animation studio Netflix Animation, who have also competed with three previous nominations for the same category, as well as the seventh non-Disney/Pixar film to win and the first non-Disney/Pixar film since Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, the second stop-motion animated film after Aardman's Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, and the Adventures of Pinocchio's second adaptation to win any category from the Academy Awards after Disney's Pinocchio.[12][61][62]

Additionally, del Toro was the first filmmaker to win Academy Awards for Best Director, Best Picture and Best Animated Feature for different films, for The Shape of Water and Pinocchio, respectively.[60]

References

- ^ a b c "Alexandre Desplat to Reteam with Guillermo del Toro on Netflix Animated Movie 'Pinocchio'". Film Music Reporter. January 8, 2020. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Acosta, Gabriel (April 27, 2021). "Pinocchio empieza a cobrar vida en el Taller del Chucho en Guadalajara (Pinocchio begins to come to life at El Taller del Chucho in Guadalajara)". Publimetro (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 21, 2021. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio at BFI London Film Festival". Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ "New Pinocchio film gives jump start to Jalisco animation studio". mexiconewsdaily.com. January 11, 2022. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (August 31, 2017). "Guillermo del Toro's 'Pinocchio' Isn't Dead Yet, But He Needs $35 Million to Make It". IndieWire. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- ^ "Netflix Blitz at Annecy: 'Entergalactic' Date; New Pics from 'Pinocchio,' 'Sea Beast'; 'LD+R' Featurette". June 15, 2022. Archived from the original on June 16, 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ Netflix Film [@NetflixFilm] (August 19, 2020). "Set during the rise of Fascism in Mussolini's Italy, PINOCCHIO — a musical directed by del Toro and Mark Gustafson (FANTASTIC MR. FOX) with a score by Alexandre Desplat — is a story of love and disobedience as Pinocchio struggles to live up to his father's expectations" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ 2023|Oscars.org

- ^ 'Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio' Wins Best Animated Feature Film | 95th Oscars (2023)

- ^ Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio Wins Best Animated Motion Picture | 2023 Golden Globe Awards on NBC - official YouTube channel

- ^ a b "Guillermo del Toro Makes History with 2023 Golden Globes Win". Netflix Tudum. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ "2023 Oscars: 'Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio' wins best animated feature". ABC7 News. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Breznican, Anthony (June 14, 2022). "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio Carves a New Path: An Exclusive First Look". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 14, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio Puts a Fantastical Spin on a Classic Tale".

- ^ Fischer, Russ (July 23, 2010). "Guillermo del Toro's Next Film to be Horror; Also Producing Stop-Motion Pinocchio and Horror Anthology TV Series - /Film". Slashfilm.

- ^ "Long-awaited 'Pinocchio' by Guillermo del Toro will finally become a movie at Netflix". artchive.ru. October 31, 2018. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n McIntyre, Gina (August 16, 2022). "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio". Netflix Queue. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ How Guillermo del Toro & Mark Gustafson Carved Their Own 'Pinocchio' Using Lessons From Hollywood, And Fascism – Contenders LA3C

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (February 17, 2011). "Guillermo Del Toro Starting Stop-Motion 'Pinocchio' Feature With Henson And Pathe". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on February 23, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (May 17, 2012). "Del Toro to helm 'Pinocchio' for Jim Henson Co". Variety. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ Chitwood, Adam (June 7, 2012). "New Artwork from Guillermo del Toro's Stop-Motion Animated PINOCCHIO". Collider.

- ^ Schaefer, Sandy (May 10, 2012). "Guillermo del Toro to Co-Direct 3D Stop-Motion 'Pinocchio' Flick". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Trumbore, Dave (January 23, 2017). "Guillermo del Toro's Stop-Motion Movie 'Pinocchio' Adds 'Over the Garden Wall' Creator". Collider. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (August 31, 2017). "Guillermo del Toro's 'Pinocchio' Isn't Dead Yet, But He Needs $35 Million to Make It". IndieWire. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio Movie Is 'Not Happening'". Screen Rant. November 8, 2017. Archived from the original on November 11, 2017. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- ^ "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio 'as far as you can get' from Disney version, says one of film's writers - Syfy Wire". October 27, 2020. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ Lang, Brent (October 22, 2018). "Guillermo del Toro Directing 'Pinocchio' for Netflix". Variety. Archived from the original on September 27, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ For 'Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio,' a Star Built From Tiny Gears and 3-D Printing

- ^ Casio, Jerome (December 12, 2022). Pinocchio's Main Villain Was Changed Halfway Through Production.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio: Handcarved Cinema (2022)

- ^ Pitman, Robert (December 10, 2022). "Del Toro's Pinocchio Removes The Scariest Disney Scene (& Makes It Worse!)". ScreenRant.

- ^ How Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio Survived Decades in the Hollywood Wilderness

- ^ "Guillermo Del Toro Approached by Daniel Radcliffe, Wants Tom Waits and Christopher Walken for 'Pinocchio'". May 18, 2012. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ "10 curiosidades sobre Pinocchio de Guillermo del Toro". December 19, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2022.

- ^ a b "David Bradley: Nie chciałem być znany jedynie jako facet z Harry'ego Pottera [WYWIAD]". January 31, 2020. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (August 19, 2020). "Cate Blanchett, Ewan McGregor, Tilda Swinton & More Round Out Cast For Guillermo del Toro Netflix 'Pinocchio' Movie". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Hullender, Tatiana (December 10, 2022). "Pinocchio's Finn Wolfhard & Gregory Mann On Working With Guillermo Del Toro". ScreenRant.

- ^ Sippell, Margeaux (November 18, 2022). "Cate Blanchett Voices the Monkey in Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio, and She Calls It Her Spirit Animal". MovieMaker. Retrieved December 22, 2022.

- ^ Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio: A Timeless Tale Told Anew

- ^ Lambertucci, Constanza (November 24, 2022). "Dentro del taller de animación donde 'Pinocho' cobró vida en México". El País. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ Radish, Christina (August 23, 2012). "Screenwriter/Composer Nick Cave Talks LAWLESS, Transitioning into Screenwriting, Guillermo del Toro's PINOCCHIO, THE THREEPENNY OPERA, and More". Collider. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ Trumbore, Dave (November 6, 2018). "Netflix Sets Guillermo del Toro's 'Pinocchio' and Henry Selick's 'Wendell & Wild' for 2021". Collider. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ De Wit, Alex (January 14, 2021). "Netflix Unveils 2021 Animated Film Slate, Including Sony Pictures Animation's 'Wish Dragon' And Two Aardman Specials". Cartoon Brew. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ Mancuso, Vinnie (December 1, 2021). "Exclusive: Guillermo del Toro Offers Update on His 'Frankenstein'-Inspired 'Pinocchio', Reveals Release Window". Collider. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (January 24, 2022). "Guillermo del Toro's 'Pinocchio' Debuts First Stop-Motion Footage, Netflix Sets December Release". Variety. Archived from the original on March 1, 2022. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ Tangcay, Jazz (March 3, 2023). "Netflix's 'All Quiet on the Western Front' Clocks More Than 150 Million Hours Viewed Since Release (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ Szalai, Georg (August 31, 2022). "Guillermo Del Toro's 'Pinocchio' to Get London Film Festival World Premiere". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 31, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- ^ "AFI Fest Adds 'Bardo', 'The Son', 'She Said', 'Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio', More to Red Carpet Lineup". September 20, 2022.

- ^ "'Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio' Teaser Trailer Drops". The Hollywood Reporter. July 27, 2022. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Netflix [@netflix] (November 9, 2022). "People are sometimes afraid of things they don't know... Academy Award® winning filmmaker Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio is now playing in select theaters and on Netflix December 9" (Tweet). Retrieved November 10, 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio". TIFF.net. November 2, 2022. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ "Guillermo del Toro proyectará Pinocho gratis tras cancelación de Cinemex" [Guillermo del Toro to screen Pinocchio for free after Cinemex cancellation]. Grupo Milenio (in Mexican Spanish). November 25, 2022. Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- ^ "Cuándo van a proyectar Pinocho de Guillermo del Toro en el Zócalo" [When will Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio be screened at the Zócalo?]. El Universal (in Spanish). December 21, 2022. Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- ^ "Así fue la noche en la que "Pinocho", de Guillermo del Toro, llegó al Zócalo" [This was the night that Guillermo del Toro's "Pinocchio" came to the Zócalo]. El Universal (in Spanish). December 31, 2022. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- ^ "MoMA Presents: Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- ^ "Guillermo del Toro: Crafting Pinocchio | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- ^ "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Nordyke, Kimberly (March 12, 2023). "Oscars: Complete Winners List". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Lang, Jamie (March 13, 2023). "2023 Academy Awards: 'Guillermo Del Toro's Pinocchio,' 'The Boy, The Mole, The Fox, And The Horse,' 'Avatar' Win Oscars". Cartoon Brew. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ Perkins, Chris. "Awards News: 'Guillermo Del Toro's Pinocchio' Wins At BAFTAs, VES Awards". AFA: Animation For Adults : Animation News, Reviews, Articles, Podcasts and More. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

External links

- 2022 films

- 2020s American animated films

- 2020s musical films

- 2020s stop-motion animated films

- 2022 animated films

- 2022 directorial debut films

- 2022 fantasy films

- American fantasy films

- American musical comedy films

- Mexican animated films

- Mexican children's films

- Mexican musical comedy films

- English-language Mexican films

- English-language Netflix original films

- Animated films set in Italy

- Animated musical films

- Best Animated Feature Annie Award winners

- Best Animated Feature BAFTA winners

- Best Animated Feature Film Golden Globe winners

- Best Animated Feature Broadcast Film Critics Association Award winners

- 2020s dark fantasy films

- Films about the afterlife

- Films about Fascist Italy

- Films about fascists

- Films directed by Guillermo del Toro

- Films scored by Alexandre Desplat

- Films set in 1916

- Films set in the 1910s

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films shot in Mexico

- Films shot in France

- Films shot in Portland, Oregon

- Films with screenplays by Guillermo del Toro

- The Jim Henson Company films

- Magic realism films

- Netflix Animation films

- Pinocchio films

- Stop-motion animated films

- American World War I films

- American World War II films

- American children's animated musical films

- American children's animated comedy films

- American children's animated drama films

- Films produced by Guillermo del Toro

- Films produced by Lisa Henson

- 2020s English-language films

- 2020s Mexican films

- Cultural depictions of Benito Mussolini

- Films about child death

- Best Animated Feature Academy Award winners