Baird Auditorium

The Baird Auditorium is a multi-purpose 530-seat venue located on the ground floor of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C..

History

As one of the oldest public performance venues and lecture halls at the Smithsonian, the Baird Auditorium's history of events is as diverse as the Smithsonian itself. Located beneath the National Museum of Natural History's rotunda, the Baird Auditorium is named for the second Secretary of the Smithsonian Spencer Fullerton Baird. The auditorium's bronze plaque recognizing Baird was laid on February 9, 1916.[1]

Architecture

In the planing phase for the new 'National Museum Building,' Smithsonian staff conveyed desire for a lecture hall and an auditorium was added to architects Hornblower & Marshall's plan in 1903.[2] The original seating capacity of the auditorium was 565 seats.[3]

The Baird Auditorium was completed in 1909, designed and built by the R. Guastavino Company under the direction of Rafael Guastavino.[4] The Baird Auditorium is one of the finest examples of the Guastavino tile arch system, inspired by the Catalan vault, in the United States. The American Institute of Architects calls the Baird Auditorium the museum's "greatest interior space."[5] According to architectural scholar Dr. John Ochsendorf, the Baird Auditorium's "daring geometry" in tile construction by the Guastavino company "spans 90 feet (27 meters) with a remarkable shallow dome in acoustical tile, and could only have been built by a company with decades of experience in tile vaulting."[6]

The pilaster bases for the Baird's walls are made of pink Tennessee marble, with the auditorium floor finished primarily in terrazzo. As Richard Rathbun, the Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in Charge of the United States National Museum, describes, "The pilaster lines are recalled by border lines of pink Tennessee and Sienna marbles enclosing panels of terrazzo."[7]

In 2020, the Grunley Construction Company, Inc. undertook exterior building renovations to the National Museum of Natural History's National Mall entrances to make them wheelchair accessibility-friendly, as well as a complete retrofit of the Baird's HVAC system.[8]

Public Closures

In late-December 1917 the Baird Auditorium was closed to the public and turned over to the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, along with other committee rooms of the Natural History building (then, the 'National Museum').[9]

Notable Speaking Engagements

Science

While the Baird Auditorium and National Museum building were still under construction, on September 27, 1908 the International Congress on Tuberculosis held an assembly of delegates for its proceedings in the auditorium and other museum spaces, with Robert Koch, discoverer of the tuberculosis bacillus, in attendance.[3]

Scientific groups and lectures have been core to the Baird's events roster near as long as the space has existed, including the 1912: "usual annual April meeting of the National Academy of Sciences, the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Institute of Architects, and the Red Cross conference."[10] The 1913 "Annual Report of the Smithsonian" also makes mention that, "Meetings of various scientific organizations were held in the Museum auditorium and adjacent rooms, and there were several formal receptions which are noted in the report of the assistant secretary."[11]

The Baird Auditorium was the location of the 'Great Debate' in the field of astronomy, also called the 'Shapley–Curtis Debate,' on April 26, 1920 on the topics of spiral nebulae and the size of the universe. NASA educational resources describe the Baird debate: "It is now clear that a once little-heard-of discussion was at the crux of a major change of humanity's view of our place in the universe;"[12] and, Dr. Frank She claims that the "debate illustrates forcefully how tricky it is to pick one's way successfully through the treacherous ground that characterized research at the frontiers of science."[13] Astrophysicist Robert Nemiroff organized a 75th anniversary event where Polish astronomer Bohdan Paczynski and University of Chicago astrophysicist Donald Q Lamb debated "The Distance Scale to Gamma Ray Bursts" in the Baird Auditorium.[14]

Canadian anthropologist Wade Davis spoke in the Baird on April 27, 2005.[15]

Arts and Culture

On October 31, 1933, African American writer and philosopher Alain Locke gave a lecture and screened films from the Harmon Foundation as part of the Smithsonian exhibition, "Exhibition of Works by Negro Artists," and sponsored by Carter G. Woodson's Association for the Study of Negro Life and History.[16] (At the time the National Mall was a desegregated area of Washington, making the Baird one of the few racially integrated theatres prior to the National Theatre's desegregation in May 1952.[17]) According to VCU professor Tobias Wofford, "On Woodson’s invitation, Locke delivered a slide lecture to the ASNLH congregants in the auditorium adjacent to the exhibition space. The lecture explored the links between African and African American art."[18] While Locke's "address was noted prominently by most of the accounts of the exhibition," Locke himself viewed it as participating in "a reaction of racial vanity."[18] Seventy-nine years later on October 31, 2012, six-time world champion boxer and Olympic gold medalist Sugar Ray Leonard spoke on the same stage in a conversation with former Washington Redskins and Washington Senators stadium announcer, Phil Hochberg.[19]

At a town hall held on November 16, 2005, Director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture Lonnie Bunch presented the final four potential sites for construction of the new Smithsonian museum.

The Baird Auditorium was host to events of the third conference of the Radio Preservation Task Force project, co-hosted by the Library of Congress in April 2023.[20]

Politics

President Warren Harding spoke in the auditorium during the second annual meeting of the Business Organization of the Government in 1922.[3]

In May 1995 Sirikit the queen of Thailand spoke in the Baird Auditorium after "reviewing the museum's Thai collections."[21]

Memorials

Senators Elihu Root and Henry Cabot Lodge spoke in the Baird Auditorium on May 10, 1912 as part of a memorial tribute to Francis D. Millet, a painter and National Gallery of Art advisory committee member who perished on board the H.M.S. Titanic.[10]

Performances

The Baird Auditorium has a long and illustrious history of musical performances. As early as 1914 the Baird was used for "Friday Morning Music Club" performances that celebrated American music.[22]

"Jazz at the Smithsonian"

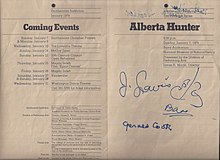

Blues singer Alberta Hunter performed at the Baird on several occasions during her late-1970s 'comeback' career period, including: on January 7, 1977[23], and in a filmed performance on November 29, 1981, which received commercial home video release as, "Alberta Hunter: Jazz at the Smithsonian," originally released in 1982.[24]

Country Music Performances

Mother Maybelle Carter performed in the Baird just three years before her passing, accompanied by her daughter Helen Carter Jones, her grandson David Carter Jones, Mike Seeger, and Ralph Rinzler, on May 18, 1975; National Public Radio recorded the performance as "Folk Festival USA," part of the Smithsonian's "Women in Country Music" series.[25] Merle Travis gave a country guitar music concert in the Baird Auditorium on October 23, 1976.[26] On June 2, 1978 the "Texas Troubador" Ernest Tubb performed as part of the Smithsonian's American Country Music series.[27]

In 1979 the Sons of the Pioneers were honored with a "National Treasure" designation by the Smithsonian Division of Performing Arts, which hosted a performance by the group in the Baird Auditorium.[28]

Other Notable Musical Performances

In early February 1977, Muddy Waters performed in the Baird as part of the Smithsonian Institution's blues series presented by the Division of Performing Arts.[29] Pete Seeger and Sweet Honey in the Rock performed an evening of "protest songs from Colonial times to today," together on the Baird's stage on January 8, 1978.[30]

In 1990 Bill Kirchner, a Jazztimes Critics' Poll "Best Emerging Jazz Arranger" winner, performed "Yes, Yes, Nonet!" with a nine-member orchestra.[31]

Jazz great Wynton Marsalis performed a Young People's Concert in the Baird Auditorium with the Wynton Marsalis Septet on June 7, 1994.[32]

David Byrne promoted his 2012 book, "How Music Works," with a talk held in the Baird Auditorium on October 1, 2012.[33]

Motion Picture Screenings

The Terrors of the Deep (1914)

One of the earliest documented film screenings in the Baird Auditorium took place during on July 16, 1914, consisting of: "illustrations of marine life below the surface of the sea at the Bahama Islands by means of moving pictures. The films were the first of their kind known to have been taken, and this was the first occasion of their public display, arranged through the courtesy of the Submarine Film Corporation."[34] Research by film scholars Q. David Bowers and Ned Thanhouser indicates that the Carl Louis Gregory-photographed The Terrors of the Deep (a.k.a. At the Bottom of the Ocean) was this underwater film, "shown privately at the Smithsonian Institution and the National Press Club in Washington, D.C."[35] Advertisement for a subsequent screening published in The Evening Standard (New Rochelle) on July 23, 1914, claim, "One of the most thrilling scenes is of Ernest Williamson, one of the inventors, killing an eight-foot man-eating shark underwater. The pictures are highly educational, for they show in animated monotone exactly what one would see through the glass of the submarine chamber in which Mr. Gregory worked. A lecture on the pictures was delivered by Dr. F.N. Glover, a well known lecturer and geographer, who explained the pictures when they were shown privately at the Smithsonian Institute."[36]

Other early screenings

The Baird hosted an annual meeting of The American Fisheries Society in September and October 1914, where, "two lectures on the salmon industry of the Pacific coast, illustrated by moving pictures, were given."[34] Illustrated lectures in the Baird became commonplace, with the 1916 Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution Secretary highlighting a wide array of lectures and discourses, "profusely illustrated, both motion pictures and lantern slides being used."[1]

The year 1917 saw the Bureau of Commercial Economics give "an exhibition of lantern slides and motion pictures relative to the prevention of contagious diseases, for the benefit of the Council of National Defense."[37] Supporting the war effort in 1917, the Baird was host to "two exhibitions of motion pictures relating to Army aeronautics for the Signal Corps of the United States Army," and employed by the Bureau of Commercial Economics for motion picture screenings given to Army officers.[9] According to a Smithsonian publication celebrating the building's anniversary, "The auditorium, one of the few in Washington, was in such demand that by 1917 a special fireproof booth had been built for the motion-picture and stereopticon machines."[3]

Motion picture films produced by the Harmon Foundation were screened alongside Alain Locke's lecture on African and African American art on October 31, 1933.[16]

Film Screening Series

Beginning in November 1974 the Smithsonian's Department of Education hosted film screenings and lectures in the auditorium as part of a program that lasted at least until 1985.[9] From September 1975 to April 1976 over 25,000 visitors to the Baird watched over 140 films and film programming, including: "documentaries on art and artists, as well as avant-garde and experimental cinema and a special Saturday series featuring works in animation particularly selected for children [...] new films, talks by artist-filmmakers, screenings of works by sixteen independent filmmakers, and lectures on film as an art form."[38]

The Baird Auditorium has served as one of the host sites for the Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital since 1994.[39] The auditorium has been home to the Mother Tongue Film Festival since its inception in 2016, and was site of the festival's first screening on February 21, 2016 of 5 short films followed by, "Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope (1977; George Lucas) dubbed into Diné bizaad (Navajo) with English subtitles."[40]

References

- ^ a b Smithsonian Institution (1916). Annual Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for the year ending June 30, 1916. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 45.

- ^ Field, Cynthia R.; Tilman, Jeffrey T. (2004). "Creating a Model for the National Mall: The Design of the National Museum of Natural History". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 63 (1): 57 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d Yochelson, Ellis Leon (1985). The National Museum ot Natural History: 75 years in the Natural History Building. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 179, 180. ISBN 9780087479890.

- ^ "How Do You Support a 5-ton Elephant?". Bookworm History. November 17, 2015. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Moeller, Gerard Martin (2022). AIA guide to the architecture of Washington, DC. American Institute of Architects (6th ed.). Baltimore. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4214-4384-3. OCLC 1272882861.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ochsendorf, John Allen (2010). Guastavino vaulting : the art of structural tile. Michael Freeman. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-56898-741-5. OCLC 769114424.

- ^ Rathbun, Richard (1913). A Descriptive Account of the Building Recently Erected for the Departments of Natural History of the United States National Museum (1st ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 43–45.

- ^ "National Museum of Natural History, Southside Improvements". Grunley Construction. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ a b c Smithsonian Intitution (1918). Annual Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for year ending June 30, 1918. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 40.

- ^ a b Smithsonian Institution (1912). Annual Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for the year ending June 30, 1912. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 24.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution (1913). Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for the year ending June 30, 1913. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 28.

- ^ "`Great Debate' Lesson Plan for Undergraduates". apod.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Shu, F. (1982). The Physical Universe, An Introduction to Astronomy. Mill Valley, California: University Science Books. p. 286. ISBN 9780935702057.

- ^ Nemiroff, Robert J. (December 1995). "The 75th Anniversary Astronomical Debate on the Distance Scale to Gamma-Ray Bursts: an Introduction". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 107: 1131.

- ^ "Record Wade Davis, Baird Auditorium, #1, 4/27/2005, MiniDV | Collections Search Center, Smithsonian Institution". collections.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ a b Brock, Charles (Summer 2019). "Toward a History of Modernism in Washington: The 1933 Display of Art by African Americans at the Smithsonian Institution's National Gallery of Art". American Art. 33 (2): 4–10. doi:10.1086/705620. S2CID 202516579.

- ^ WETA. "How Helen Hayes Helped Desegregate the National Theatre". Boundary Stones: WETA's Washington DC History Blog. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ a b Wofford, Tobias (Summer 2019). "Perspectives on the 1933 Exhibition: Herring, Locke, and Porter". American Art. 33 (2): 11–16. doi:10.1086/705621. S2CID 202515088.

- ^ "THE SMITHSONIAN ASSOCIATES PRESENTS 'SUGAR RAY'S BIG FIGHT: INSIDE THE WORLD OF BOXING'". US Fed News (USA). September 17, 2012. p. 2.

- ^ A Century of Broadcasting: Preservation and Renewal (PDF). Washington, DC: Radio Preservation Task Force. 2023.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution (1995). Annals of the Smithsonian Institution, 1995 (PDF). Washignton, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. p. 85. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution (1914). Annual Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for the year ending June 30, 1914. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 44.

- ^ Sumrall, Harry (January 8, 1979). "Alberta Hunter". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ United States Copyright Registration. Type of Work: Motion Picture; Registration Number / Date: PA0000163741 / 1982-12-17; Title: Alberta Hunter / a production of Adler Enterprises, Ltd.; produced and directed by Clarke Santee [i.e. Clark Santee] and Delia Gravel Santee. Imprint: McLean, Va.: Distributed by Adler Video Marketing, c1982. Description: 1 videocassette (58 min.) : sd., col. ; 3/4 in.; Series: Jazz at the Smithsonian. Notes: Host: Willis Conover. Deposit includes descriptive folder (4 p.); Copyright Claimant: Adler Enterprises, Ltd.; Date of Creation: 1981. Date of Publication: 1982-04-22. Authorship on Application: Adler Enterprises, Ltd., employer for hire. Copyright Note: C.O. correspondence.

- ^ "Mother Maybelle Carter and the Carter family [sound recording]. 1975-05-18. 2 sound tape reels : analog, 7 1/2 ips, full track ; 10 in.manuscripts 1 folder. Local shelving no.: LWO 8906AFS 18089-18090AFC 1976/018". Library of Congress, American Folklife Center.

- ^ "October at the Smithsonian Institution" (PDF). The Smithsonian Torch. Vol. 76–9. October 1976. p. 5. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Summers, K.C. (June 2, 1978). "Ernest Tubb". The Washington Post. p. 3.

- ^ "Awards". Sons of the Pioneers. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved 2022-08-26.

- ^ Harris-Hurd, Laura (February 5, 1977). "Muddy Waters Warms Washington Crowd". New York Amsterdam News. pp. D15.

- ^ Richmond, Phyllis C. (January 8, 1978). "Where Has All the Protest Gone?". The Washington Post. p. 39.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution (1990). Smithsonian Year 1990 Supplement: Appendices and Chronology (1st ed.). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 258.

- ^ "Record Wynton Marsalis Talks Jazz | Collections Search Center, Smithsonian Institution". collections.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ "THE SMITHSONIAN ASSOCIATES PRESENTS 'DAVID BYRNE IN CONVERSATION'". US Fed News (USA). September 17, 2012. p. 2.

- ^ a b Smithsonian Institution (1915). Annual Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for the year ending June 1915. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 37.

- ^ Thanhouser, Ned. "TERRORS OF THE DEEP, THE". www.thanhouser.org. Retrieved 2022-08-26.

- ^ "[Advertisement]". The Evening Standard (New Rochelle). July 23, 1914. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution (1917). Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for the year ending June 30, 1917. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 43.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution (1976). Smithsonian Year 1976. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. p. 184.

- ^ Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital (1994). "Printed Program" (PDF). DC Environmental Film Festival. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-09-01. Retrieved 2023-09-01.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution (2021). 2016-2020 Mother Tongue Film Festival: Five Year Progress Report (PDF). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. p. 9.

External links

- Event Space Rental website for Baird Auditorium, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

- "Alberta Hunter: Jazz at the Smithsonian" (1982) home video release of her 1981 performance at the Baird Auditorium, streaming on YouTube

- Video lecture by film scholar Ned Thanhouser about the Submarine Film Corporation's early underwater movies, which premiered in the Baird Auditorium in 1914.