Economy of Turkey

| |

| Currency | Turkish lira (TRY, ₺) |

|---|---|

| Calendar year[1] | |

Trade organisations | G-20, OECD, EU Customs Union, WTO, MIKTA, BSEC, ECO, OTS, D-8 and others |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth | |

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

Population below poverty line | |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Average gross salary | TRY 7.830/ $405.86 monthly[18] (2022) |

| TRY 10,003 / $518.54 annual (2022) | |

Main industries | |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | |

Import goods | |

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| −1.5% (of GDP) (2017 est.)[1] | |

| Revenues | [1] |

| Expenses | 185.8 billion (2017 est.)[1] |

| Economic aid | donor: $6.182 billion, 0.79% of GNI.[26][27] |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

| Economy of Turkey |

|---|

|

|

|

Turkey is a founding member of the OECD and G20, and is classified among the E7 countries, EAGLEs and NICs.[34][35][36] As of 2023, Turkey's economy is the 19th-largest in the world by nominal GDP, and the 11th-largest by PPP. According to the IMF, Turkey has an upper-middle income mixed-market emerging economy.[37] The country is among the world's leading producers of agricultural products, textiles, motor vehicles, transportation equipment, construction materials, consumer electronics and home appliances.

Turkey's nominal GDP peaked at $1.029 trillion in 2023,[6] while its nominal GDP per capita peaked at $12,489 in 2013.[38][39] Turkey's GDP (PPP) resulted to $3.573 trillion in 2023,[6] while its GDP (PPP) per capita increased to $41,412 in 2023.[6] The declining value of the Turkish lira, especially during the ongoing Turkish currency and debt crisis, has had a significant impact on the recent decrease in the country's USD-based nominal GDP figures.[38] High inflation continues to be a problem in the early 2020s.[40]

Over the past 20 years, there have been major developments in the financial and social aspects of Turkey's economy, such as increases in employment and average income since 2000.[41] Turkey has recently slowed down in its economic progress, due to considerable changes in external and internal factors, as well as a reduction in the government's economic reforms.[41] Environmentalists have argued that the economy is excessively dependent on the construction and contracting sector.[42] President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's unorthodox monetary policy increased inflation and devalued the currency in recent years.[43]

Macroeconomic trends

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: https://www.keepeek.com//Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/economics/oecd-economic-surveys-turkey-2021_2cd09ab1-en. (February 2021) |

According to Eurostat data, Turkish GDP per capita adjusted by purchasing power standards stood at 64% of the EU average in 2018.[44] Turkey's labour force participation rate of 61.5% is by far the lowest of the OECD states which have a median rate of 78%.[45] 2017 was the second consecutive year that saw more than 5.000 high net-worth individuals (HNWIs, defined as holding net assets of at least $1 million) leaving Turkey, reasons given as government crackdown on the media deterring investment, and loss of currency value against the U.S. dollar.[46]

A longstanding characteristic of the Turkish economy is a low savings rate.[47] Since under the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey has been running huge and growing current account deficits, reaching $7.1 billion by January 2018, while the rolling 12-month deficit rose to $51.6 billion,[48] one of the largest current account deficits in the world.[47] The economy has relied on capital inflows to fund private-sector excess, with Turkey's banks and big firms borrowing heavily, often in foreign currency.[47] Under these conditions, Turkey must find about $200 billion a year to fund its wide current account deficit and maturing debt, always at risk of inflows drying up, having gross foreign currency reserves of just $85 billion.[49]

Turkey has been meeting the "60% Maastricht criteria" of the EU for government debt stock since 2004.[citation needed] Similarly, from 2002 to 2011, the budget deficit decreased from more than 10% to less than 3%, which is one of the EU's Maastricht criteria for the budget balance.[50] In January 2010, International credit rating agency Moody's Investors Service upgraded Turkey's rating one notch.[51][52] In 2012, credit ratings agency Fitch upgraded Turkey's credit rating to investment grade after an 18-year gap,[53] followed by a ratings upgrade by credit ratings agency Moody's Investors Service in May 2013, as the service lifted Turkey's government bond ratings to the lowest investment grade, Moody's first investment-grade rating for Turkey in two decades and the service stated in its official statement that the nation's "recent and expected future improvements in key economic and public finance metrics" was the basis for the ratings boost.[54][55] In March 2018, Moody's downgraded Turkey's sovereign debt into junk status, warning of an erosion of checks and balances under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.[56] In May 2018, credit ratings agency Standard & Poor's cut Turkey's debt rating further into junk territory, citing widening concern about the outlook for inflation amid a sell-off in the Turkish lira currency.[57]

Share prices in Turkey nearly doubled over the course of 2009.[58] On 10 May 2017, the Borsa Istanbul (BIST-100 Index), the benchmark index of Turkey's stock market, set a new record high at 95,735 points.[59] As of 5 January 2018, the Index reached 116,638 points.[60] However, in the course of the 2018 Turkish currency and debt crisis,[61][62] the index dipped back below 100.000 in May.[63] In early June, the BIST-100 Index dropped to the lowest level in dollar terms since the global financial crisis in 2008.[64]

In 2017, the OECD expected Turkey to be one of the fastest growing economies among OECD members during 2015–2025, with an annual average growth rate of 4.9%.[65] In May 2018, Moody's Investors Service lowered its estimate for growth of the Turkish economy in 2018 from 4% to 2.5% & in 2019 from 3.5% to 2%.[66]

According to a 2013 Financial Times Special Report on Turkey, Turkish business executives and government officials believed the quickest route to achieving export growth lies outside of traditional western markets.[67] While the European Union used to account for more than half of all Turkey's exports, by 2013 the figure was heading down toward not much more than a third.[67] However, by 2018 the share of exports going to the EU was back above fifty percent.[68] Turkish companies' foreign direct investment outflow has increased by 10 times over the past 15 years, according to the 2017 Foreign Investment Index.[69][70][71]

With policies of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan fuelling the construction sector, where many of his business allies are active,[72] Turkey as of May 2018 had around 2 million unsold houses, a backlog worth three times average annual new housing sales.[73] The 2018 Turkish currency and debt crisis ended a period of growth under Erdoğan-led governments since 2003, built largely on a construction boom fueled by easy credit and government spending.[74]

In 2018, Turkey went through a currency and debt crisis, characterised by the Turkish lira (TRY) plunging in value, high inflation, rising borrowing costs, and correspondingly rising loan defaults. The crisis was caused by the Turkish economy's excessive current account deficit and foreign-currency debt, in combination with the ruling Justice and Development Party's (AKP) increasing authoritarianism and President Erdoğan's unorthodox ideas about interest rate policy.[75][49][76]

On 10 August 2018, Turkish currency lira nosedived following Donald Trump's tweet about doubling tariffs on Turkish steel and aluminum that day.[77] The currency weakened 17% that day and has lost nearly 40% of its value against the dollar till that time. The crash of the lira has sent ripples through global markets, putting more pressure on the euro and increasing investors' risk aversion to emerging-market currencies across the board.[77] On 13 Aug., South Africa's rand slumped nearly 10%, the biggest daily drop since June 2016. Lira crisis spotlighted deeper concerns about the Turkish economy that have long signaled turmoil long ago.[77]

By the end of 2018, Turkey went into recession. The Turkish Statistical Institute claimed that the Turkish economy declined by 2.4% in the last quarter of 2018 as compared to the previous quarter. This followed a 1.6% drop the previous quarter.[78] Lira shrank down to 30% against the US dollar in 2018.[79]

In May 2019, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) released an economic outlook in which it is reported that Turkey's economy will probably see a gradual recovery of growth to around 2.5 percent in 2020.[80]

According to official data in December 2022, Turkey's annual inflation rate rose to a 24-year high of 85.51% in October. This was slightly below expectations after the central bank cut interest rates despite rising prices. Inflation has surged since the lira collapsed last year after the central bank began cutting rates in an easing cycle long sought by President Tayyip Erdogan.[81] In June 2023, Turkey's first female central bank governor raised the benchmark interest rate from 8.5% to 15%, ending Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's insistence on keeping inflation rates low. [82]

-

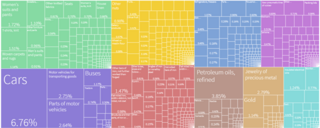

The structure of Turkey's GDP by sectors.[83]

-

GDP per capita (PPP) of Turkey vs other emerging economies. The data is retrieved from World Bank

-

Public debt of the six major European countries between 2002 and 2009 as a percentage of GDP

-

Turkey expected to increase its GDP in long term due to population growth and urbanization.

Data

The following table shows the main economic indicators from 1980 to 2021 (with IMF staff estimates in 2022–2027). Inflation below 10% is in green.[84]

| Year | GDP

(in Bil. US$PPP) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ PPP) |

GDP

(in Bil. US$nominal) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ nominal) |

GDP growth

(real) |

Inflation rate

(in Percent) |

Unemployment

(in Percent) |

Government debt

(in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 159.2 | 3,516.3 | 96.6 | 2,133.7 | 7.2% | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | |||||||

| 1982 | n/a | |||||||

| 1983 | n/a | |||||||

| 1984 | n/a | |||||||

| 1985 | n/a | |||||||

| 1986 | n/a | |||||||

| 1987 | n/a | |||||||

| 1988 | n/a | |||||||

| 1989 | n/a | |||||||

| 1990 | n/a | |||||||

| 1991 | n/a | |||||||

| 1992 | n/a | |||||||

| 1993 | n/a | |||||||

| 1994 | n/a | |||||||

| 1995 | n/a | |||||||

| 1996 | n/a | |||||||

| 1997 | n/a | |||||||

| 1998 | n/a | |||||||

| 1999 | n/a | |||||||

| 2000 | 51.3% | |||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | ||||||||

| 2023 | ||||||||

| 2024 | ||||||||

| 2025 | ||||||||

| 2026 | ||||||||

| 2027 |

Main economic sectors

In 2022, the sector with the highest number of companies registered in Turkey is Manufacturing with 240,998 companies followed by Wholesale Trade and Services with 197,125 and 186,983 companies respectively.[85]

Agricultural sector

Agriculture is still an important sector of Turkey's economy, and the country is one of the world's top ten agricultural producers.[86] Wheat, sugar beet, milk, poultry, cotton, vegetables and fruit are major products;[87] and Turkey is the world's largest grower of hazelnuts,[88] apricots,[87] and oregano.[89]

Half of Turkey's land is agricultural,[87] and farming employs about 15% of the workforce,[90] but under half a million farmers.[91][92] It provides about 10% of exports[93] and over 5% of gross domestic product (GDP).[94] Over 380 billion lira of agricultural subsidy is budgeted for 2024.[95]

Despite being a major food producer, Turkey is a net wheat importer, much of it coming from Russia and Ukraine.[96] Turkey is the European Union (EU)'s fourth largest vegetable supplier and the seventh largest fruit supplier. Turkey would like to extend the EU Customs Union Agreement to agricultural products.[97]

Around half of Turkey's agricultural greenhouse gas is due to cattle.[a] According to the World Bank, the sector should adapt more to climate change in Turkey and make technical improvements.[91] Strategic planning is the responsibility of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, but no plan for 2024 onwards has yet been published.[99][100] Almost all the seeds used in Turkey are produced domestically.[101]Industrial sector

This section needs to be updated. (April 2019) |

Consumer electronics and home appliances

Turkey's Vestel is the largest TV producer in Europe, accounting for a quarter of all TV sets manufactured and sold on the continent in 2006.[102] By January 2005, Vestel and its rival Turkish electronics and white goods brand Beko accounted for more than half of all TV sets manufactured in Europe.[103] Another Turkish electronics brand, Profilo Telra, was Europe's third-largest TV producer in 2005.[104] EU market share of Turkish companies in consumer electronics has increased significantly following the Customs Union agreement signed between the EU and Turkey: in color TVs from 5% in 1995 to more than 50% in 2005, in digital devices from 3% to 15%, and in white goods from 3% to 18%.

Textiles and clothing

Turkish companies made clothing exports worth $13.98 billion in 2006; more than $10.67 billion of which (76.33%) were exported to EU member states.[105]

Vakko, Beymen, Yargıcı, Mavi Jeans, Ipekyol, Les Benjamins, Colin's, Nocturne, LC Waikiki, Derimod, DESA and Koton are some of the biggest fashion brands in Turkey.

Motor vehicles and automotive products

The automotive industry in Turkey, which plays an important role in the manufacturing sector of the Turkish economy, produced 1,276,140 motor vehicles in 2021, ranking as the 13th largest producer in the world (production peaked at 1,695,731 motor vehicles in 2017, when Turkey also ranked 13th).[106] Turkish automotive companies like TEMSA, Otokar and BMC are among the world's largest van, bus and truck manufacturers. Togg, or Turkey's Automobile Joint Venture Group Inc. is the first all-electric vehicle company of Turkey.

The automotive industry is an important part of the economy since the late 1960s. The companies that operate in the sector are mainly located in the Marmara Region. With a cluster of car-makers and parts suppliers, the Turkish automotive sector has become an integral part of the global network of production bases, exporting over $22.94 billion worth of motor vehicles and components in 2008.[111][112]

Global car manufacturers with production plants include Fiat/Tofaş, Oyak-Renault, Hyundai, Toyota, Honda and Ford/Otosan. Turkish automotive companies like TEMSA, Otokar and BMC are among the world's largest van, bus and truck manufacturers. Togg is a new Turkish automotive company established in 2018 for producing EVs.[109][113] Togg's factory in Gemlik, Bursa Province, was inaugurated on 29 October 2022, the 99th anniversary of the Turkish Republic.[110]

Turkey's annual auto exports, including trucks and buses, surpassed 1 million units for the first time in 2016 as foreign automakers' investment in new models and a recovery in its mainstay European market lifted shipments. According to industry group the Automotive Manufacturers Association, or OSD, Turkey exported 1.14 million units in 2016, up 15% from the year before. Auto exports hit a record high for the fourth straight year. Production grew 9% year on year in 2016 to 1.48 million units, setting a new record for the second consecutive year. Nearly 80% of vehicles produced in Turkey were exported.[114]

Multiple unit trains, locomotives and wagons

TÜLOMSAŞ (1894), TÜVASAŞ (1951) and EUROTEM (2006) are among the major producers of multiple unit trains, locomotives and wagons in Turkey, including high-speed EMU and DMU models.

Bozankaya is a Turkish manufacturer of rolling stock including metro, tram and trolleybus vehicles in Ankara.

Defense industry

Turkey has many modern armament manufacturers. Annual exports reached $1.6 billion in 2014.[133] MKEK, TAI, Aselsan, Roketsan, FNSS, Nurol Makina, Otokar, and Havelsan are major manufacturers. On 11 July 2002, Turkey became a Level 3 partner of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) development program. TAI builds various aircraft types and models, such as the F-16 Fighting Falcon for the Turkish Air Force.[134][135] Turkey has recently launched domestically built new military/intelligence satellites including a 0.8m resolution reconnaissance satellite (Project Göktürk-1) for use by the Turkish Armed Forces and a 2m resolution reconnaissance satellite (Project Göktürk-2) for use by the Turkish National Intelligence Organization.

Other important products include the TAI TF Kaan, TF2000-class destroyer, Milgem class corvette, Baykar MIUS Kızılelma UCAV, Baykar Akıncı HALE UCAV, Baykar Bayraktar TB2 MALE UCAV, TAI Aksungur MALE UCAV, TAI Anka MALE UAV/UCAV, Aselsan İzci UGV, Altay main battle tank, T-155 Fırtına self-propelled howitzer, J-600T missile, T-129 attack helicopter, A400M, Roketsan UMTAS anti-tank missile, Roketsan Cirit laser-guided rocket, Panter howitzer, ACV-300, Otokar Cobra and Akrep, BMC Kirpi, FNSS Pars 6x6 and 8x8 APC, Nurol Ejder 6x6 APC, TOROS artillery rocket system, Bayraktar Mini UAV, ASELPOD, and SOM cruise missile.

Steel-Iron industry

Turkey ranks 8th in the list of countries by steel production. In 2013, total steel production was 29 million tonnes.[136] Turkey's crude steel production reached a record high of 34.1 million tons in 2011.[137] Notable producers (above 2 million tonnes) and their ranks among top steel producing companies.[138]

- Erdemir (7.1 million tonnes) (47th) (Only Erdemir-Turkey; Erdemir-Romania is not included)

- Habaş (4.4 million tonnes) (72nd)

- İçdaş (3.6 million tonnes) (76th)

- Diler (2.3 million tonnes) (108th)

- Çolakoğlu (2.1 million tonnes) (110th)

Science and technology

TÜBİTAK is the leading agency for developing science, technology and innovation policies in Turkey.[139] TÜBA is an autonomous scholarly society acting to promote scientific activities in Turkey.[140] TAEK is the official nuclear energy institution of Turkey. Its objectives include academic research in nuclear energy, and the development and implementation of peaceful nuclear tools.[141]

Turkish government companies for research and development in military technologies include Turkish Aerospace Industries, ASELSAN, HAVELSAN, ROKETSAN, MKE, among others. Turkish Satellite Assembly, Integration and Test Center is a spacecraft production and testing facility owned by the Ministry of National Defence and operated by the Turkish Aerospace Industries. The Turkish Space Launch System is a project to develop the satellite launch capability of Turkey. It consists of the construction of a spaceport, the development of satellite launch vehicles as well as the establishment of remote earth stations.[142][143][144]

Construction and contracting sector

The Turkish construction and contracting industry is made up of a large number of businesses, the largest of which was ranked 40th in the world by size. In 2016 a total of 39 Turkish construction and contracting companies were listed in the Top 250 International Contractors List prepared by the Engineering News-Record.[145][146]

Over half of Turkey's building stock contravenes housing regulations. An amnesty program to register illegal constructed buildings brought in $3.1 billion, but the safety issues largely remain. In mid-February 2019, an eight-story building that was registered in the amnesty collapsed killing 21 people. As Turkey is prone to strong earthquakes, poor building quality is even more concerning.[147]

Service sector

This section needs to be updated. (April 2019) |

Transport

The first quarter of 2023 has brought promising signs of recovery for Turkey's economy. According to the latest data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat), the country's gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 6.7% year-on-year in the first three months of the year.

This growth is largely attributed to increased domestic demand, particularly in the construction and manufacturing sectors. Additionally, exports have also been on the rise, with a 12.2% increase in the first quarter compared to the same period last year.

The government's efforts to boost the economy through various stimulus measures and reforms have also played a role in this recovery. The implementation of structural reforms, including improvements to the business environment and a reduction in bureaucratic procedures, have attracted more foreign investment and boosted investor confidence.

However, there are still challenges to be addressed, including high inflation and unemployment rates. Inflation reached a record high of 61.04% in March 2023, and the unemployment rate remains above 10%. These challenges highlight the need for continued efforts to strengthen the economy and ensure sustainable growth.

In 2013 there were ninety-eight airports in Turkey,[148] including 22 international airports.[149] As of 2015[update], Istanbul Atatürk Airport is the 11th busiest airport in the world, serving 31,833,324 passengers between January and July 2014, according to Airports Council International.[150] The new (third) international airport of Istanbul is planned to be the largest airport in the world, with a capacity to serve 150 million passengers per annum.[151][152][153]

The state-owned utility Turkish State Railways operates the 12,740–km railway network, 23rd longest in the world. Since 2003, Turkish State Railways has also been investing in high-speed rail lines, which at 2,175 km (1,353 mi) ranked ninth longest in the world.[157]

As of 2010, the country had a roadway network of 426,951 km, including 2,080 km of expressways and 16,784 km of divided highways.[161]

As of 2010, the Turkish merchant marine included 1,199 ships (604 registered at home), ranking 7th in the world.[162] Turkey's coastline has 1,200 km of navigable waterways.[162]

In 2008, 7,555 kilometres (4,694 mi) of natural gas pipelines and 3,636 kilometres (2,259 mi) of petroleum pipelines spanned the country's territory.[162]

Communications

As of 2008, there were 17,502,000 operational landline telephones in Turkey, which ranked 18th in the world;[162] while there were 65,824,000 registered mobile phones in the country, which ranked 15th in the world during the same year.[162] The largest landline telephone operator is Türk Telekom, which also owns TTNET, the largest internet service provider in Turkey. The largest mobile phone operators in the country are Turkcell, Vodafone Turkey, Avea and TTNET Mobil.

The telecommunications liberalisation process started in 2004 after the creation of the Telecommunication Authority, and is still ongoing. Private sector companies operate in mobile telephony, long-distance telephony and Internet access. Additional digital exchanges are permitting a rapid increase in subscribers; the construction of a network of technologically advanced intercity trunk lines, using both fiber-optic cable and digital microwave radio relay, is facilitating communication between urban centers.[162]

The remote areas of the country are reached by a domestic satellite system, while the number of subscribers to mobile-cellular telephone service is growing rapidly.[162]

The main line international telephone service is provided by the SEA-ME-WE 3 submarine communications cable and by submarine fiber-optic cables in the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea that link Turkey with Italy, Greece, Israel, Bulgaria, Romania, and Russia.[162] In 2002, there were 12 Intelsat satellite earth stations; and 328 mobile satellite terminals in the Inmarsat and Eutelsat systems.[162]

Türksat A.Ş. is the primary communications satellite operator of Turkey, controlling the Turksat series of satellites. Göktürk-1, Göktürk-2 and Göktürk-3 are Turkey's earth observation satellites for reconnaissance, operated by the Turkish Ministry of National Defense. BILSAT-1 and RASAT are the scientific observation satellites operated by the TÜBİTAK Space Technologies Research Institute, which (together with Turkish Aerospace Industries and Aselsan) also takes part in the production of Turkey's satellites.

As of 2001, there were 16 AM, 107 FM, and 6 shortwave radio stations in the country.[162]

As of 2015, there were 42,275,017 internet users in Turkey, which ranked 15th in the world;[162] while as of 2012, there were 7,093,000 internet hosts in the country, which ranked 16th in the world.[162]

Tourism

In 2019, Turkey ranked sixth in the world in terms of the number of international tourist arrivals, with 51.2 million foreign tourists visiting the country.[163] Over the years, Turkey has emerged as a popular tourist destination for many Europeans, competing with Greece, Italy and Spain. Resorts in provinces such as Antalya and Muğla (which are located on the Turkish Riviera) have become very popular among tourists.

Banking and finance

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (April 2022) |

The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (Türkiye Cumhuriyet Merkez Bankası) was founded in 1930, as a privileged joint-stock company. It possesses the sole right to issue notes. It also has the obligation to provide for the monetary requirements of the state agricultural and commercial enterprises. All foreign exchange transfers are exclusively handled by the central bank.

Originally established as the Ottoman Stock Exchange (Dersaadet Tahvilat Borsası) in 1866, and reorganized to its current structure at the beginning of 1986, the Istanbul Stock Exchange (ISE) is the sole securities market of Turkey.[164] During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Bankalar Caddesi (Banks Street) in Istanbul was the financial center of the Ottoman Empire, where the headquarters of the Ottoman Central Bank (established as the Bank-ı Osmanî in 1856, and later reorganized as the Bank-ı Osmanî-i Şahane in 1863)[165] and the Ottoman Stock Exchange (1866) were located.[166] Bankalar Caddesi continued to be Istanbul's main financial district until the 1990s, when most Turkish banks began moving their headquarters to the modern central business districts of Levent and Maslak.[166] In 1995, the Istanbul Stock Exchange moved to its current building in the Istinye quarter.[167] The Istanbul Gold Exchange was also established in 1995. The stock market capitalisation of listed companies in Turkey was valued at $161,537,000,000 in 2005 by the World Bank.[168]

Until 1991, establishing a private sector bank in Turkey was subject to strict government controls and regulations. On 10 October 1991 (ten days before the general elections of 20 October 1991) the ANAP government of Prime Minister Mesut Yılmaz gave special permissions to five prominent businessmen (who had close links to the government) to establish their own small-scale private banks. These were Kentbank (owned by the Süzer Group); Park Yatırım Bankası (owned by Karamehmet); Toprakbank (owned by Toprak); Bank Ekspres (owned by Betil); and Alternatif Bank (owned by Doğan.) They were followed by other small-scale private banks established between 1994 and 1995, during the DYP government of Prime Minister Tansu Çiller, who introduced drastic changes to the banking laws and regulations; which made it very easy to establish a bank in Turkey, but also opened many loopholes in the system. In 1998, there were 72 banks in Turkey; most of which were owned by construction companies that used them as financial assets for siphoning money into their other operations.

As a result, in 1999 and 2001, the DSP government of Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit had to face two major economic crises that were caused mostly by the weak and loosely regulated banking sector; the growing trade deficit; and the devastating İzmit earthquake of 17 August 1999. The Turkish lira, which was pegged to the U.S. dollar prior to the crisis of 2001, had to be floated, and lost an important amount of its value. This financial breakdown reduced the number of banks to 31. Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit had to call the renowned economist Kemal Derviş to tidy up the economy and especially the weak banking system so that a similar economic crisis would not happen again.

At present, the Turkish banking sector is among the strongest and most expansive in East Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia.[citation needed] During the past decade since 2001, the Turkish lira has also gained a considerable amount of value and maintained its stability,[citation needed] becoming an internationally exchangeable currency once again (in line with the inflation that dropped to single-digit figures since 2003.) The economy grew at an average rate of 7.8% between 2002 and 2005. Fiscal deficit is benefiting (though in a small amount) from large industrial privatizations. Banking came under stress beginning in October 2008 as Turkish banking authorities warned state-run banks against the pullback of loans from the larger financial sectors.[177] More than 34% of the assets in the Turkish banking sector are concentrated in the Agricultural Bank (Ziraat Bankası), Housing Bank (Yapı Kredi Bankası), Isbank (Türkiye İş Bankası) and Akbank. The five big state-owned banks were restructured in 2001. Political involvement was minimized and loaning policies were changed. There are also numerous international banks, which have branches in Turkey. A number of Arabian trading banks, which practice an Islamic banking, are also present in the country.

Government regulations passed in 1929 required all insurance companies to reinsure 30% of each policy with the Millî Reasürans T.A.Ş. (National Reinsurance Corporation) which was founded on 26 February 1929.[178] In 1954, life insurance was exempted from this requirement. The insurance market is officially regulated through the Ministry of Commerce.

After years of low levels of foreign direct investment (FDI), in 2007 Turkey succeeded in attracting $21.9 billion in FDI and is expected to attract a higher figure in following years.[179] A series of large privatizations, the stability fostered by the start of Turkey's EU accession negotiations, strong and stable growth, and structural changes in the banking, retail, and telecommunications sectors have all contributed to the rise in foreign investment. [citation needed]

In recent years,[citation needed] the chronically high inflation has been brought under control and this has led to the launch of a new currency, the "New Turkish lira", on 1 January 2005, to cement the acquisition of the economic reforms and erase the vestiges of an unstable economy.[180] On 1 January 2009, the New Turkish lira was renamed once again as the "Turkish lira", with the introduction of new banknotes and coins.

Medical tourism

There are numerous private hospitals in Turkey, which has benefited from medical tourism in recent years. Health tourism generated revenues worth $1 billion in 2019 for Turkey's economy.[181] A total of 662,087 patients were treated at Turkish hospitals in 2019 within the scope of health tourism, with around 60% of the income being obtained from plastic surgeries.[181]

Largest companies

In 2022, 9 Turkish companies were listed in the Forbes Global 2000 list – an annual ranking of the top 2000 public companies in the world by Forbes magazine.[182] Banking industry leads with 4 companies in the list followed by airline, automotive and metallurgy industry with 1 companies each. There are also 2 conglomerates. As of 2022, listed companies were:

| World Rank | Company | Industry | Revenue (billion $) |

Profits (billion $) |

Assets (billion $) |

Market Value (billion $) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 626 | Koç Holding | Conglomerate | 38.84 | 1.7 | 76.85 | 6.79 |

| 884 | İş Bankası | Banking | 12.25 | 0.94 | 95.42 | 3.2 |

| 902 | Sabancı Holding | Conglomerate | 10.51 | 1.35 | 61.73 | 2.79 |

| 1224 | Turkish Airlines | Airline | 10.91 | 0.92 | 26.64 | 3.72 |

| 1262 | Akbank | Banking | 5.97 | 0.94 | 61.91 | 3.22 |

| 1353 | Halkbank | Banking | 7.66 | 0.52 | 93.67 | 1.97 |

| 1381 | VakıfBank | Banking | 7.66 | 0.51 | 85.49 | 2.22 |

| 1478 | Erdemir | Metallurgy | 7.64 | 1.74 | 9.52 | 8.04 |

| 1793 | Ford Otosan | Automotive Industry | 7.96 | 0.98 | 3.23 | 7.17 |

Long term GDP forecasts

The following table is an OECD Long Term Projections made in February 2022 for largest 16 economies by GDP using PPP exchange rates from 2030 to 2060. [183]

| 2021 | Country | 2030 | Country | 2040 | Country | 2050 | Country | 2060 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26,656 | 36,977 | 47,306 | 54,765 | 62,140 | |||||

| 22,675 | 24,302 | 28,063 | 33,363 | 42,204 | |||||

| 10,181 | 16,603 | 25,083 | 32,119 | 36,527 | |||||

| 5,585 | 5,632 | 7,507 | 9,846 | 12,320 | |||||

| 4,743 | 5,309 | 5,908 | 6,060 | 7,068 | |||||

| 4,328 | 4,566 | 4,914 | 5,934 | 6,333 | |||||

| 3,507 | 4,233 | 4,776 | 5,362 | 5,891 | |||||

| 3,328 | 3,759 | 4,624 | 5,168 | 5,746 | |||||

| 3,231 | 3,653 | 4,492 | 4,882 | 5,407 | |||||

| 3,174 | 3,375 | 3,832 | 4,620 | 5,340 | |||||

| 2,749 | 3,267 | 3,800 | 4,249 | 4,768 | |||||

| 2,613 | 3,073 | 3,679 | 4,148 | 4,736 | |||||

| 2,610 | 2,675 | 2,866 | 2,959 | 3,366 | |||||

| 2,436 | 2,499 | 2,692 | 2,880 | 3,104 | |||||

| 2,027 | 2,094 | 2,370 | 2,698 | 3,066 | |||||

| 1,959 | 2,062 | 2,362 | 2,694 | 3,046 |

External trade and investment

This section needs to be updated. (April 2019) |

As of 2016, the main trading partners of Turkey are Germany, Russia and the United Kingdom, UAE, Iraq, Italy and China, many being top in both export as well as import.[184] Turkey has taken advantage of a customs union with the European Union, signed in 1995, to increase industrial production for exports, while benefiting from EU-origin foreign investment into the country.[185] In addition to Customs Union, Turkey has free-trade agreements with 22 countries.[186]

A very large aspect of Turkey trade revolves around the automotive industry, where its top exports are cars, accounting for $13.2 billion. Other top exports from the country are gold, delivery trucks, vehicle parts and jewelry, which are respectively, $6.96 billion, $5.04 billion, $4.64 billion, and $3.39 billion. These values are calculated using the 1992 revision of the Harmonized System classification. Comparatively, it imports many of the same industries, such as, gold valued at $17.1 billion, refined petroleum at $9.8 billion, cars at $8.78 billion, vehicle parts at $6.34 billion and scrap iron at $5.84 billion.[187]

Turkey is also a source of foreign direct investment in central and eastern Europe and the CIS, with more than $1.5 billion invested. 32% has been invested in Russia, primarily in the natural resources and construction sector, and 46% in Turkey's Black Sea neighbours, Bulgaria and Romania. Turkish companies also have sizable FDI stocks in Poland, at about $100 million.

The construction and contracting companies, such as Enka, Rönesans Holding and Tekfen, have been significant players in the country's economy.

Without a carbon price exporters to the EU will have to pay the CBAM from 2026.[188]

Turkey had many improvements in the ease of doing business index. Its rank increased from 68th in 2017 to 33th in 2020. As of 2021, it was performing better than countries like the Netherlands and Belgium.[189][190][191]

Natural resources

Energy

Turkey's energy trade deficit was over $US80 billion in 2022,[194] causing a large foreign trade deficit.[195] Europe supports energy efficiency and renewable energy via the €1 billion Mid-size Sustainable Energy Financing Facility (MidSEFF) to finance investments in these areas.[196][197] Energy subsidies amounted to 200 billion lira in 2021.[198] Up to 150kWh per month of free electricity is provided to two million poor families.[199]

Fatih Birol, the head of the International Energy Agency said in 2019 that, because of its falling price, the focus should be on maximizing onshore wind power in Turkey.[200] The economics of coal power has been modelled by Carbon Tracker.[201] They estimate that for new plants both wind and solar is already cheaper than coal power.[202] And they forecast that existing coal plants will be more expensive than new solar by 2023 and new wind by 2027.[202]

Most energy deals in 2019 were for renewables, and over half the investment in these was from outside the country.[203] The external costs of fossil fuel consumption in 2018 has been estimated as 1.5% of GDP.[204] The government sets the price of residential gas and electricity,[205] and as of 2018[update], for residential consumers, "high cost is the most important problem of Turkey's energy system".[206]

In 2022, the energy import bill was 97 billion USD. Keeping consumer prices low is a political priority.[194]Renewable energy

Renewables supply a quarter of energy in Turkey, including heat and electricity. Some houses have rooftop solar water heating, and hot water from underground warms many spas and greenhouses. In parts of the west hot rocks are shallow enough to generate electricity as well as heat. Wind turbines, also mainly near western cities and industry, generate a tenth of Turkey’s electricity. Hydropower, mostly from dams in the east, is the only modern renewable energy which is fully exploited. Hydropower averages about a fifth of the country's electricity, but much less in drought years.[207] Apart from wind and hydro, other renewables; such as geothermal, solar and biogas; together generated almost a tenth of Turkey’s electricity in 2022.[208] Over half the installed capacity for electricity generation is renewables.[209]: section 4.2.1

Turkey has a long history of wood burning, windmills, and bathing in hot springs. Many dams were built from the mid-20th to early 21st century, but some say that governments have not allowed civil society enough influence on energy policy, leading to protests against building dams, geothermal power plants, and at least one wind farm.[210] Despite Turkey’s sunny climate solar power is underdeveloped. As the electricity system is already flexible increasing to 70% renewables is easily feasible.[211]: 21 Solar power could be expanded more quickly if the electricity grid was improved faster and energy policy revised, especially by abolishing fossil fuel subsidies.

Many hybrid power plants are planned, and batteries are being integrated. Companies with a lot of renewables include the state electricity generation company (mainly hydro), Aydem, and Kalyon. If renewables could help phase-out coal by 2030, instead of by the national net zero greenhouse gas emissions target year of 2053, that would have significant health benefits and reduce inflation in Turkey.[212] As of 2022 renewables are not sufficient to meet that target year.[213] Various electric vehicles are being manufactured, which will use some of the increased renewable generation and help reduce air pollution.Fossil fuels

Gas

Natural gas supplies over a quarter of Turkey's energy.[215][216] The country consumes 50 to 60 billion cubic metres of this natural gas each year,[217][218] nearly all of which is imported. A large gas field in the Black Sea however started production in 2023.[219]

After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine several European countries stopped buying Russian oil or gas, but Turkey's relations with Russia are good enough that it continues to buy both.[220][221] Turkey receives almost half of its gas from Russia.[218] As of 2023[update] wholesale gas is expensive and a large part of the import bill.

Households buy the most gas, followed by industry and power stations.[222] Over 80% of the population has access to gas,[223] and it supplies half the country's heating requirements.[217] As the state owned oil and gas wholesaler BOTAŞ has 80% of the gas market,[215]: 16 the government can and does subsidize residential and industrial gas consumers.[224] All industrial and commercial customers, and households using more than a certain amount of gas, can switch suppliers.[215]Oil

Oil supplies over a quarter of Turkey's energy.[225][226] Because the country produces very little oil,[227] it is almost completely dependent on imports of oil and oil products such as petrol and diesel,[228] over half of which is consumed in the country's road vehicles.[229] Turkey is the world's largest user of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) for road transport.[230]

Because Turkey produces only 7% of the oil it consumes, the country's total imports are worth more than its exports, which is a problem for its economy.[231] After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, several European countries stopped buying Russian oil, petrol and diesel but Turkey's relations with Russia are such that it supplies most such imports.[232][233][234]Coal

Coal supplies a quarter of Turkey's primary energy.[235] The heavily subsidised coal industry generates over a third of the country's electricity[236] and emits a third of Turkey's greenhouse gases.

Coal is a major contributor to air pollution, and damages health across the nation, being burnt even in homes and cities.[237] It is estimated that a phase out of coal power in Turkey by 2030 instead of by the 2050s would save over 100 thousand lives.[238] Flue gas emission limits are in place, but data from mandatory reporting is not made public.

Over 90% of coal mined in Turkey is lignite (brown coal),[235] which is more polluting than other types of coal.[239] Turkey's energy policy encourages mining lignite for coal-fired power stations in order to reduce gas imports;[236] and coal supplies over 40% of domestic energy production.[240] Mining peaked in 2018, at over 100 million tonnes,[241] declined considerably in 2019,[242] but increased again in 2022.[243] Most coal is imported,[244][245] as in contrast to local lignite production, Turkey imports most of its bituminous coal from Russia.[246] Coal consumption probably peaked in 2022.[243] The largest coalfield in Turkey is Elbistan.[247]Minerals

Turkey is the tenth-ranked producer of minerals in the world in terms of diversity. Around 60 different minerals are currently produced in Turkey. The richest mineral deposits in the country are boron salts, Turkey's reserves amount to 72% of the world's total. According to the CIA World Factbook, other natural resources include iron ore, copper, chromium, uranium, antimony, mercury, gold, silver, barite, borate, celestine (strontium), emery, feldspar, limestone, magnesite, marble, perlite, pumice, pyrites (sulfur) and clay.

In 2019, the country was the 2nd largest world producer of chromium;[248] the world's largest producer of boron;[249] 6th largest world producer of antimony;[250] 9th largest world producer of lead;[251] 13th largest world producer of iron ore;[252] 11th largest world producer of molybdenum;[253] 4th largest world producer of gypsum;[254] 15th largest world producer of graphite;[255] in addition to being the 11th largest world producer of salt.[256]

As a gold producer Turkey is currently ranked 22nd globally. Hosting some of the largest gold deposits in the European continent it is currently Europe's largest gold producer, producing 42 Tonnes of gold in 2020.[257] World class deposits include Kisladag Mine 17Moz and Copler 10Moz. The country hosts 18 mid sized deposits from 1-10Moz gold, these include the Kiziltepe Gold Mine, Salinbas, Hod Maden, Ovacik and Efemcukuru.

Environment

Almost all post-covid stimulus was detrimental to the environment, with Russia being the only worse country.[258] In the 21st century, Turkey's fossil fuel subsidies are around 0.2% of GDP,[259][260] including at least US$14 billion (US$169 per person) between January 2020 and September 2021.[261] Data on finance for fossil fuels by state-owned banks and export credit agencies is not public.[262]

Employment

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2021) |

In 2021 trade unions complained that TurkStat data showed unemployment falling whereas that of the government employment agency showed it rising.[263] Environmentalists argue that some actions to improve the environment would also benefit the economy, for example: that investing in wind power in Turkey and solar power in Turkey would create jobs and is competitive with fossil fuels.[264]

Regional disparities

According to Eurostat data, Turkish GDP per capita adjusted by purchasing power standards stood at 64 percent of the EU average in 2018.[44]

The country's wealth is mainly concentrated in the northwest and west, while the east and southeast suffer from poverty, lower economic production and higher levels of unemployment.[266] However, in line with the rapid growth of Turkey's GDP during the first two decades of the 21st century (with brief periods of stagnation and recession), parts of Anatolia began reaching a higher economic standard. These cities are known as the Anatolian Tigers.

Richest and poorest NUTS-2 regions (GDP PPP 2017)

Source: Eurostat – ESA 95[267]

|

Richest and poorest NUTS-1 regions (GDP PPP 2017)

Source: Eurostat – ESA 95[268]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Economic history of Turkey

- World Bank

- OECD

- National debt of Turkey

- World Gold Council

- List of companies of Turkey

- List of countries by labour force Turkey, 19th

- List of countries by real GDP growth rate Turkey, 15th

- List of countries by total wealth Turkey, 28th

- List of countries by number of millionaires Turkey, 34th

- List of countries by number of billionaires Turkey, 23rd

- List of countries with the most skyscrapers Turkey, 14th

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Turkey (Turkiye)". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ "World Economic and Financial Surveys World Economic Outlook Database—WEO Groups and Aggregates Information April 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ N. Gregory Mankiw (2007). Principles of Economics (4th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-324-22472-6.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "Population on 1 January". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. World Bank. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "IMF, June 2023".

- ^ a b c "WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK 2022 OCT Countering the Cost-of-Living Crisis". imf.org. International Monetary Fund. p. 43. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "GDP – Composition by Sector". CIA World Factbook. 2016. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ "Consumer Prices". TCMB. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ "People at risk of poverty or social exclusion". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ Europe Central Asia Economic Update, Spring 2020 : Fighting COVID-19. World Bank. 9 April 2020. pp. 75, 76. ISBN 9781464815645. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Nations, United. "Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. UNDP. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d "İşgücü İstatistikleri, Mayıs 2023". TUIK. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ "General Profile of Labour Force". data.tuik.gov.tr. TURKSTAT. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ [1]

- ^ TUIK (31 January 2023). "Foreign Trade Statistics, June 2023". TUIK. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "Turkey (TUR) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners | OEC".

- ^ a b "Foreign Trade Statistics, December 2022". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ "Foreign Trade Statistics, June 2023". tuik.gov.tr. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "Imports Products of Turkey". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ "Maxinomics". maxinomics.com. Maxinomics. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "European Economy 2017, p 127" (PDF). European Commission. 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ "Detailed summary" (PDF). oecd.org. 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "Turkey ranks second in the world for humanitarian aid, named most generous donor". Daily Sabah. 15 August 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ a b "S&P, Moody's send Turkey deeper into junk territory". Financial Times. 17 August 2018. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ "Turkiye". Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "Scope affirms Türkiye's long-term foreign-currency ratings at B- and maintains Negative Outlook". Scope Ratings. 4 August 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ "Info" (PDF). tcmb.gov.tr.

- ^ "Chronology of Turkey-EU relations". Turkish Secretariat of European Union Affairs. Archived from the original on 15 May 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- ^ "Interview with European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso on BBC Sunday AM" (PDF). European Commission. 15 October 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 November 2006. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- ^ Mauro F. Guillén (2003). "Multinationals, Ideology, and Organized Labor". The Limits of Convergence. Princeton University Press. pp. 126 (Table 5.1). ISBN 0-691-11633-4.

- ^ David Waugh (2000). "Manufacturing industries (chapter 19), World development (chapter 22)". Geography, An Integrated Approach (3rd ed.). Nelson Thornes Ltd. pp. 563, 576–579, 633, and 640. ISBN 0-17-444706-X.

- ^ N. Gregory Mankiw (2007). Principles of Economics (4th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-324-22472-6.

- ^ "IMF WEO Database of April 2022 – Emerging and Developing – Europe". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ a b "IMF World Economic Outlook Database, April 2022: Turkey, data for 2010–2027". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ "Turkey GDP – Gross Domestic Product – 2013". countryeconomy.com. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ "Annual inflation in Turkey reaches record 25-year high of 85.5%". euronews.com. Euronews. 3 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Overview". World Bank. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "There's still time for Turkey to improve its spotty climate record". The National. 8 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ "Why Turkey's currency crash does not worry Erdogan". The National. 3 December 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ a b "GDP per capita in PPS". Eurostat. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ "Employment – Labour force participation rate – OECD Data". theOECD.

- ^ "Private wealth in Turkey in decline: Report". Hurriyet Daily News. 27 February 2018.

- ^ a b c "How Turkey fell from investment darling to junk-rated emerging market". The Economist. 19 May 2018.

- ^ "Turkish current account deficit more than doubles". Ahval. 12 March 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Inflation rise poses challenge to Erdogan as election looms". Financial Times. 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Gross domestic product 2011". Turkish Statistical Institute. 21 December 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ "Moo upgrades government bond rating amidst crisis Archived 2010-01-12 at the Wayback Machine". Today's Zaman. 9 January 2010.

- ^ Eric Martin (7 August 2012). "Goldman Sachs's MIST Topping BRICs as Smaller Markets Outperform". Bloomberg News.

- ^ Butler, Daren (5 November 2012). "Turkey Regains Investment-Grade Rating After Long Wait". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Daren Butler (17 May 2013). "UPDATE 1-Turkey hails new investment grading but worries about money flows". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ Ye Xie; Selcuk Gokoluk (17 May 2013). "Turkey Raised to Investment Grade by Moody's on Debt Cuts". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ "Moody's downgrades Turkish debt". Financial Times. 8 March 2018. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ "S&P cuts Turkey's rating deeper into 'junk'". Reuters. 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Stockmarkets". The Economist. 7 January 2010.

- ^ "Borsa Istanbul Stock Exchange breaking records". Daily Sabah. 10 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Borsa Istanbul". BloombergHT. 5 January 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Turkey's leader is helping to crash its currency". The Washington Post. 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Investors lose their appetite for Turkey". Financial Times. 16 May 2018. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Borsa Istanbul Stock Exchange breaking records". Anadolu. 8 May 2018.

- ^ "Turkish stock market hits lowest since 2008 crisis". Ahval. 6 June 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ "Economic Outlook". Turkish Statistical Institute. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Turkish growth forecast almost halved at Moody's". Ahval. 30 May 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ a b Dombey, Daniel (9 May 2013). "Silk roads lead to resurgent power". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "EU's share in Turkey's exports hit 53 percent in February with sharp annual increase: Association". Hurriyet Daily News. 1 March 2018.

- ^ "Turkey Overseas Investment Rises 10 Times in 15 Years". financialtribune. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Turkey's overseas investments increase tenfold over last 15 years". Daily Sabah. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Turkish businesses FDI outflow rises 10 times in 15 years: Index". Hürriyet Daily News. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ Mark Bentley (19 April 2018). "Turkish real estate ills reflect Erdoğan's snap poll decision". Ahval. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ "Turkish property firms to slash prices in one-month drive to revive market". Reuters. 15 May 2018.

- ^ Jack Ewing (17 August 2018). "Life in Turkey Now: Tough Talk, but Fears of Drug Shortages". The New York Times.

- ^ Borzou Daragahi (25 May 2018). "Erdogan Is Failing Economics 101". Foreign Policy.

- ^ Matt O'Brien (13 July 2018). "Turkey's economy looks like it's headed for a big crash". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c "Turkey's Lessons for Emerging Economies – Caixin Global". caixinglobal.com. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Turkey's economy slides into recession". BBC News. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "Turkey's economy slips into recession, according to new figures". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "Turkey's economic rebound will be 'gradual': EBRD". France 24. 8 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "/turkeys-inflation-hits 24 year high 855 after rate cuts". Reuters.

- ^ "Archived copy". r.search.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Bluenomics". Archived from the original on 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects".

- ^ "Industry Breakdown of Companies in Turkey". HitHorizons.

- ^ "Türkiye". International Fund for Agricultural Development. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "Turkey – Country Commercial Guide". International Trade Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Hazelnuts: Turkey remains top producer". Mundus Agri. 23 March 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Uğural, İsmail (29 March 2023). "Türkiye supplies 80% of world production of Oregano". Turkish Agrinews. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Labour Force Statistics, 2022". Turkstat. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Turkey's farmers battle with soaring costs and mounting debt". Financial Times. 4 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Number of farmers in Turkey plummets below half a million". Gazete Duvar. 21 April 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "World Bank Provides $341 Million Boost to Advance Green and Competitive Growth of Turkey's Agricultural Sector". World Bank. 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Gayri̇ Safi̇ Yurti̇çi̇ Hasila Değerler" [Gross Domestic Product Values] (PDF). Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (Turkey).

- ^ "Turkey to privatize highways, bridges, and hydroelectric power plants to reduce current account deficit". Gercek News. 1 November 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Gostev, Aleksandr; Liklikadze, Koba (30 April 2022). "Analysis: Erdogan Hoping Russian Invasion Of Ukraine Can Bolster Turkish Regional Power". Radio Free Europe.

- ^ Valero, Jorge (2 August 2023). "EU and Turkey Discuss Easing Trade Relations Amid Warmer Ties". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ "Türkiye. 2023 National Inventory Report (NIR)". unfccc.int. Turkstat. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Kamuda Stratejik Yönetim |". www.sp.gov.tr. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ 2019–23 strategic plan (updated in 2022) (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.

- ^ "Bakan Pakdemirli: 'Ülkemizde kullanılan tohumlukların yüzde 96'sı yurt içinde üretilmektedir'" [Minister Pakdemirli: '96 percent of the seeds used in our country are produced domestically']. gazete banka. 21 December 2021.

- ^ Michael Kuser. "The Unknown TV Giant". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 13 June 2006.

- ^ Boulden, Jim (17 January 2005). "Turkey switches on to TV market". CNN. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- ^ "Europe's No. 3 TV Manufacturer, a Private Company: PROFILO-TELRA". Business Wire. BNET. 19 August 2005. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- ^ "The Export Performance of the Turkish Clothing Industry in 2006 Archived 2007-11-28 at the Wayback Machine," ITKIB

- ^ "2021 Statistics | www.oica.net". oica.net. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ a b Dan Mihalascu (4 November 2022). "Turkey's National Carmaker Togg Starts Production Of 2023 C SUV EV". insideevs.com.

- ^ "TOGG Official Website". togg.com.tr. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ a b Jay Ramey (30 December 2019). "Turkey Bets on EVs with the Pininfarina-Designed TOGG". autoweek.com.

- ^ a b "'A game changer': Türkiye inaugurates its first national car plant". TRT World. 30 October 2022.

- ^ "Otomotiv İhracatı 2008'de 22 Milyar 944 Milyon Dolara Ulaştı". Haberler. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ 29.08.2011 Pazartesi 15:58. "2008'de otomotiv ihracatı rekor kırdı". bankakredimnet. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "TOGG Official Website". togg.com.tr. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "Turkish auto exports hit 1m for first time in 2016". Nikkei Asian Review.

- ^ Gareth Jennings (24 November 2022). "Turkish future fighter comes together ahead of 'victory day' roll-out". janes.com.

- ^ "Turkey's Domestic 5th Generation TF-X Fighter Jet Is on the Final Assembly Line". overtdefense.com. 25 November 2022.

- ^ Gastón Dubois (8 January 2023). "TF-X/MMU: Turkey's future fifth-generation fighter is taking shape". aviacionline.com. Aviacionline.

- ^ Joseph Trevithick (10 January 2023). "Unique Sensor Setup Emerges on Turkey's Stealthy New Fighter". thedrive.com.

- ^ Anıl Şahin (17 March 2023). "Milli Muharip Uçak'ın piste çıktığı anlar". SavunmaSanayiST.

- ^ "SSB Başkanı Demir'den '18 Mart' mesajı: "MMU bugün pistin başında"". CNN Türk. 17 March 2023.

- ^ "Milli Muharip Uçak ilk kez piste çıktı". NTV. 17 March 2023.

- ^ "Images from the second day of the taxiing and ground running tests of the TAI TF-X (MMU) on 17 March 2023, released by Prof. Dr. İsmail Demir, President of the Turkish Defence Industry Agency". 17 March 2023.

- ^ Joseph Trevithick (17 March 2023). "Our First Full Look at Turkey's New TF-X Stealthy Fighter". thedrive.com.

- ^ "İlk uçuşa ilerleyen Milli Muharip Uçak sürprize hazırlanıyor". Anadolu Agency. 27 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Baykar's unmanned fighter aircraft completes first flight". baykartech.com. 15 December 2022.

- ^ Tayfun Özberk (1 May 2022). "Here Is How UAVs Will Be Recovered Aboard TCG Anadolu". navalnews.com. Naval News.

- ^ "Image of Baykar MIUS Kızılelma UCAVs deployed on TCG Anadolu (L-400)". stargazete.com. 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Bayraktar Kızılelma: Maiden Flight". Baykar Technologies. 14 December 2022.

- ^ Herk, Hans van (14 December 2022). "Kızılelma takes to the sky!". www.scramble.nl.

- ^ Emma Helfrich (11 April 2023). "Turkey's 'Drone Carrier' Amphibious Assault Ship Enters Service". thedrive.com.

- ^ "Turkish Navy Officially Welcomes Its New Flagship, TCG Anadolu". TRT World. 11 April 2023.

- ^ "TCG Anadolu (L-400) at the Bosporus strait in Istanbul". TRT Haber. 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Savunma Sanayi İhracat Artışı, Türkiye Ortalamasının Dört Katından Fazla Oldu". Milliyet. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ "Turkey signs $1.78 bln deal to buy warplanes". Reuters. 11 May 2007.

- ^ "Turkey signs contract to buy 30 F-16 block 50+ jets". F-16.net.

- ^ Türkiye Çelik Üreticileri Derneği. "Türkiye Çelik Üreticileri Derneği". dcud.org.tr. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012.

- ^ Turkish Steel Producers Association. "Turkish Steel Producers Association". dcud.org.tr. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014.

- ^ Gözlem Gazetesi. "Gözlem Gazetesi". gozlemgazetesi.com. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Who We Are? – THE SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNOLOGICAL RESEARCH COUNCIL OF TURKEY". tubitak.gov.tr.

- ^ "Türkiye Bilimler Akademisi". tuba.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ "Turkish Atomic Energy Authority – Mission of TAEK". Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ "Space Launch System Project". Undersecretariat for Defence Industries. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Bekdil, Burak Ege (28 July 2013). "Turkey's Sat-Launcher Plans Raise Concerns". Defense News. Archived from the original on 30 August 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Bekdil, Burak Ege (12 December 2013). "Turkey Spends Big on Innovation". Defense News. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ "Turkish contractors rank second in world for ninth straight year". Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ "The Top 250 International Contractors". Enr.construction.com. 24 August 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ Caglayan, Birsen Altayli (26 February 2019). "Turkish cities could become 'graveyards' with building amnesty,..." Reuters. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: Turkey". Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Study in Turkey: International Airports in Turkey". Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Year to date Passenger Traffic". ACI. 25 September 2014. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ "It will be the biggest airport of the world". 24 January 2013. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ "Istanbul's New Erdoğan-Backed Airport to Be Named After... Erdoğan". Newsweek. 14 August 2014.

- ^ Gianluca Mezzofiore (14 August 2014). "Erdogan Airport: Istanbul's Super Hub 'to be Named After Turkey's President-Elect'". International Business Times UK.

- ^ "Turkish Airlines is named the Best Airline in Europe at the 2012 World Airline Awards held at Farnborough Air Show". Skytrax. 12 July 2012. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ "Turkish Airlines named best airline in Europe for fifth year in a row – BUSINESS".

- ^ "Turkish Airlines: International Flight Destinations". Turkish Airlines. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Heper, Metin (2018). Historical Dictionary of Turkey.

- ^ Tim Gibson (11 May 2022). "Turkey Has Built the World's Longest Suspension Bridge". The B1M.

- ^ "Why Turkey Built the World's Longest Suspension Bridge". The B1M. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Groundbreaking ceremony for bridge over Dardanelles to take place on March 18". Hürriyet Daily News. 17 March 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Karayolları Genel Müdürlüğü". kgm.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "CIA World Factbook: Turkey". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ UNWTO Tourism Highlights: 2019 Edition | World Tourism Organization. 2019. doi:10.18111/9789284421152. ISBN 978-92-844-2115-2. S2CID 240665765.

- ^ "Istanbul Stock Exchange: History of the Istanbul Stock Exchange". Imkb.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Ottoman Bank Museum: History of the Ottoman Bank". Obarsiv.com. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Ottoman Bank Museum". Ottoman Bank Museum. Archived from the original on 18 May 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ "Istanbul Stock Exchange: "İMKB'nin Kuruluşundan İtibaren Önemli Gelişmeler" (Timeline of important events since 1985)". Imkb.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ Data – Finance Archived 5 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine, World Development Indicators, World Bank

- ^ a b Tuba Ongun (17 April 2023). "Istanbul Finance Center opens with inauguration of banking section". Anadolu Agency.

- ^ a b "Your Evening Briefing: A Turkish Election the Whole World Is Watching". bloomberg.com. 10 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Image of the Istanbul Financial Center". bloomberg.com. 10 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Istanbul Financial Center: Properties". ifm.gov.tr. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Image of the Istanbul Financial Center". ifm.gov.tr. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ "Mistral Towers". emporis.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019.

- ^ "Folkart Towers". emporis.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016.

- ^ "Ege Perla". emporis.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021.

- ^ Turkey warns against potential Bank Runs Archived 5 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Millî Reasürans: Tarihçe". Millire.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Yabancı sermayede rekor". Anka News Agency (in Turkish). Hürriyet. 21 February 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- ^ "Turkey knocks six zeros off lira". BBC. 31 December 2004. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- ^ a b "Health tourism earns above $1B to Turkey in 2019, under spotlight with COVID-19". Daily Sabah. Daily Sabah. 20 August 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Andrea Murphy and Isabel Contreras (12 May 2022). "The Global 2000". Forbes. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ "Economic Outlook No 109 – February 2022 – Long-term baseline projections". Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ "Foreign Trade Statistics as of October 2012". Turkish Statistical Institute. 30 November 2006. Archived from the original (Word document) on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- ^ Bartolomiej Kaminski (1 May 2006). "Turkey's evolving trade integration into Pan-European markets" (PDF). World Bank. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- ^ "T.C. Ticaret Bakanlığı". ticaret.gov.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "OEC – Turkey (TUR) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners". oec.world. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ "Turkey balks at coal phaseout amid growing energy woes – Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East". al-monitor.com. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "World Bank Group to Discontinue Doing Business Report". World Bank. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Zumbrun, Josh (16 September 2021). "World Bank Cancels Flagship 'Doing Business' Report After Investigation". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Machen, Ronald; Jones, Matthew; Varghese, George; Stark, Emily (15 September 2021). "Investigation of Data Irregularities in Doing Business 2018 and Doing Business 2020" (PDF). World Bank. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2021.

- ^ DifiglioGürayMerdan (2020), p. 37.

- ^ "Coal Phase-out in the Turkish Power Sector towards net-zero emission targets: An Integrated Assessment of Energy-Economy-Environment Modeling" (PDF).

- ^ a b Siccardi, Francesco. "Understanding the Energy Drivers of Turkey's Foreign Policy".

- ^ "Turkey's trade deficit jumps 137 per cent in 2022". Duvar. 31 January 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ "A New Strategy for EU-Turkey Energy Cooperation". Turkish Policy Quarterly. 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ "Turkey Mid-Size Sustainable Energy Financing Facility (MidSEFF)". Stantec. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Devranoglu, Nevzat; Butler, Daren (30 December 2022). "Factbox: Turkey's raft of pre-election spending to swell budget". Reuters. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ "2 milyon 22 bin ailenin 80 liraya kadar elektrik faturasını devlet ödeyecek". Diken. 28 February 2019. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ "IEA head: Turkey could benefit from energy resource glut in upcoming period". Daily Sabah. 30 December 2019. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ "Global Coal Power Economics Model Methodology" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Wind vs. Coal Power i Turkey/Solar PV vs. Coal in Turkey" (PDF). Carbon Tracker. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Energy Deals 2019 (Report). PricewaterhouseCoopers. February 2020. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ TarantoAydınalp_KöksalDal (2020).

- ^ "Erdoğan announces discounts on residence electricity and natural gas prices ahead of Turkey's elections". Hürriyet Daily News. 25 December 2018. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ "Voters in Turkey keep energy policy in mind when voting: Survey". Hürriyet Daily News. 19 March 2019. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Lessons from global experiences for accelerating energy transition in Turkey through solar and wind power (PDF) (Report). Shura. 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ "Executive Summary: Net Zero 2053: A Roadmap for the Turkish Electricity Sector" (PDF). Shura. 2023.

the share of the renewables is almost 40%

- ^ First Biennial Transparency Report of Türkiye (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Environment, Urbanisation and Climate Change. November 2024.

- ^ Tezcür, Günes Murat (2022). The Oxford Handbook of Turkish Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-006489-1.

- ^ Integration of Renewable Energy into the Turkish Electricity System (Report). Shura. 28 April 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Hanson, Matt A. (27 June 2024). "Turkey's Potential to Lead EU Decarbonization". Non Profit News | Nonprofit Quarterly. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ Ergenç, Ceren; Göçer, Derya (5 May 2023). "China's Response to Türkiye's Volatile Authoritarianism". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- ^ Kulovic, Nermina (4 February 2022). "Turkish drillship wraps up all planned well tests on Black Sea gas field". Offshore Energy. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ a b c IEA (March 2021). Turkey 2021 – Energy Policy Review (Technical report). International Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Energy consumption by source, Turkey". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ a b "A Cold Winter: Turkey and the Global Natural Gas Shortage". Centre for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies (Edam). 6 October 2021. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Ukraine War Complicates Turkey's Gas Challenge". Energy Intelligence. 9 March 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "Can Sakarya pave the way for Turkey's gas independence?". IHS Markit. 25 April 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Bakheit, Nesreen; Imahashi, Rurika (9 June 2022). "China, India and Turkey to siphon more Russian oil ahead of EU ban". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ Dezem, Vanessa (28 June 2022). "EU Gas Swings as Russia-Turkey Flows Resume While Risks Loom". BNN Bloomberg. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ Ergur, Semih (5 June 2022). "Increasing Usage of Natural Gas in Turkey and Its Effect on Local Economy". Climate Scorecard. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ 2021 Natural Gas Distribution Sector Report (PDF). Natural Gas Distribution Companies Association of Turkey (GAZBİR) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Coskun, Orhan (31 March 2022). "Turkey may hike April industry, power plant gas prices more than 20% -sources". Reuters. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ IEA (March 2021). Turkey 2021 – Energy Policy Review (Technical report). International Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Energy consumption by source, Turkey". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Oil and Gas – Turkey". International Trade Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Adal, Hikmet (25 February 2022). "Russia-Ukraine war: How will it affect Turkey's economy?". Bianet. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ DifiglioGürayMerdan (2020), pp. 203.

- ^ DifiglioGürayMerdan (2020), pp. 206.

- ^ "Turkey's current account deficit at $4.1 bln in November; $48 billion in 2022". Reuters. 6 January 2023. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Bakheit, Nesreen; Imahashi, Rurika (9 June 2022). "China, India and Turkey to siphon more Russian oil ahead of EU ban". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ Dezem, Vanessa (28 June 2022). "EU Gas Swings as Russia-Turkey Flows Resume While Risks Loom – BNN Bloomberg". BNN Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "Russia top energy supplier to Turkey despite Western sanctions".

- ^ a b "Türkiye - Countries & Regions". IEA. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Coal". Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey). Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Turkey failing to adopt international air quality standard values, groups say". Ahval. 30 March 2022.

Homes and businesses in many Turkish cities burn coal, including the cheap and highly polluting lignite, to produce energy for heating and other purposes.

- ^ Curing Chronic Coal: The health benefits of a 2030 coal phase out in Turkey (Report). Health and Environment Alliance. 2022.

- ^ "Lignite coal – health effects and recommendations from the health sector" (PDF). Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL). December 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ Ersoy (2019), p. 5.

- ^ "Turkey breaks local coal production record in 2018". Anadolu Agency. 16 January 2019. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Di̇reskeneli̇, Haluk (3 January 2020). "Enerji piyasalarında 2020 yılı öngörüleri" [2020 energy market outlook]. Enerji Günlüğü (in Turkish).

- ^ a b "Rise in European demand for energy jolts Turkey's fading coal industry". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ Yackley, Ayla Jean (3 March 2022). "Turkish inflation pushes past 54% as food and energy prices soar". Financial Times. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "Social and Employment Impacts of Climate Change and Green Economy Policies in Türkiye | United Nations Development Programme". UNDP. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Türkiye Electricity Review 2024 (PDF) (Report). Ember.