F-flat major

| Relative key | D-flat minor (theoretical) →enharmonic: C-sharp minor |

|---|---|

| Parallel key | F-flat minor (theoretical) →enharmonic: E minor |

| Dominant key | C-flat major enharmonic: B major |

| Subdominant | B-double flat major (theoretical) →enharmonic: A major |

| Enharmonic | E major |

| Component pitches | |

| F♭, G♭, A♭, B | |

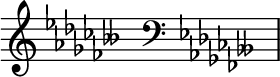

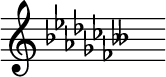

F-flat major (or the key of F-flat) is a theoretical key based on F♭, consisting of the pitches F♭, G♭, A♭, B![]() , C♭, D♭, and E♭. Its key signature has one double flat and six flats.[1]

, C♭, D♭, and E♭. Its key signature has one double flat and six flats.[1]

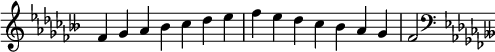

The F-flat major scale is:

Its relative minor is D-flat minor, usually replaced by C-sharp minor (see reason below) and its parallel minor is F-flat minor, which is normally replaced by E minor, since F-flat minor's four double-flats make it generally impractical to use. Because of that, it is usually enharmonic to E major with 4 sharps.

Music in F-flat major

Although F-flat major is usually notated as its enharmonic equivalent of E major, because E major has four sharps only as opposed to F-flat major's eight flats (including the B![]() ), F-flat major appears as a secondary key area in several works in flat keys. Part of Richard Strauss' Metamorphosen uses F-flat major, which one commentator has called "a bitter enharmonic parody" of the earlier manifestations of E major in the piece.[2]

), F-flat major appears as a secondary key area in several works in flat keys. Part of Richard Strauss' Metamorphosen uses F-flat major, which one commentator has called "a bitter enharmonic parody" of the earlier manifestations of E major in the piece.[2]

Beethoven also used F-flat major in his Piano Sonata No. 31, Op. 110. In the first movement's exposition, the transitional passage between the first and second subjects consists of arpeggiated figuration beginning in A-flat major and modulating to the dominant key of E-flat major. In the recapitulation, the key for this passage is changed to bring the second subject back in A-flat major: the transitional passage appears in a key that would theoretically be F-flat major, but which is notated in E major, presumably because Beethoven judged this easier to read – this key being a major third below the key of the earlier appearance of this passage. Likewise, the second movement (in A-flat major) of Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 8 (Pathétique) contains six measures of what would theoretically be F-flat major, but notated as E major (keeping the 4-flat key signature of the movement, so every note in the passage has an accidental).

Another example of F-flat major being notated as E major can be found in the Adagio of Haydn's Trio No. 27 in A-flat major. The Finale of Bruckner's Symphony No. 4 employs enharmonic E for F-flat, but its coda employs F-flat directly, with a Phrygian cadence through F-flat onto the tonic.[3][4][5]

An example of F-flat major being used directly is in Victor Ewald's Quintet No. 4 in A-flat major (Op. 8), where the entirety of the third movement is notated in this key.[6]

The climax that occurs in the middle of Samuel Barber's Adagio for Strings resolves to F-flat major.[citation needed] The final cadence of John Rutter's setting of Robert Herrick's poem "What Sweeter Music" is in F-flat major.[citation needed]

In Bach's Prelude and Fugue in E-flat minor, a brief section in bar 26 of the piece modulates to F-flat major.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Nicolas Slonimsky (1960). The Road to Music. New York: Dodd, Mead, & Co. p. 16.

- ^ Bryan Randolph Gilliam (1998). Richard Strauss: New Perspectives on the Composer and His Work. Duke University Press. p. 237. ISBN 0-8223-2114-9.

- ^ Donald Betts (2005). "Beethoven's Piano Sonata Opus 110". The Inner Voice.

- ^ James Arnold Hepokoski; Warren Darcy (2006). Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press. p. 326. ISBN 0-19-514640-9.

- ^ Julian Horton (2004). Bruckner's Symphonies: Analysis, Reception and Cultural Politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 127. ISBN 0-521-82354-4.

- ^ "Ewald: Quintet No 4 in Ab, op 8". Ensemble Publications. Retrieved 1 June 2016.