History of Périgueux

The history of Périgueux catalogues, studies and interprets all the events, both ancient and more recent, associated with this French town.

Although Périgueux has been inhabited since prehistoric times, the first city, named Vesunna, dates back to ancient Rome. Under the Roman Empire, Périgueux became a powerful city in Gallia Aquitania . During the barbarian invasions, Vesunna was destroyed around 410. A new fortified center, called Puy-Saint-Front, developed towards the end of the 10th century. Until the 13th century, political power was entirely in the hands of the bishop, who jealously guarded his town's autonomy. It wasn't until 1250 that the bourgeoisie began to counterbalance his authority, a century before the town finally submitted to the kingdom of France.

During the Renaissance, Périgueux continued to develop, becoming a commercial crossroads for the region. But this first golden age was cut short by the Wars of Religion, during which many merchants were pillaged. During the absolute monarchy, Périgueux remained a modest city in France, whose main asset was its position as a commercial crossroads. Under the French Revolution, the city officially became the administrative centre of the Dordogne department.

It wasn't until the reign of Napoleon that the town experienced an urban boom, merging with the commune of Saint-Martin in 1813. The Belle Époque saw the rise of numerous industries - notably metallurgy and railroad workshops. World War II saw Périgueux, located in the Zone Libre, become the center of several Resistance networks.

After the war, Périgueux quickly recovered its urban, economic and political standing.

Prehistory

It was during the Acheulean and, above all, the Mousterian periods that the first human settlements appeared on the site of present-day Périgueux, at the foot of the plateau almost encircled by the River Isle.[1] Various sites from this period have been uncovered in the Périgueux area, notably at Sept Fonts (right bank),[2] Croix du Duc, Gour de l'Arche, Jambes, Petit-Puy-Rousseau, Toulon, and north of the Tourny alleys.[3] The Isle valley attracted animal and human populations thanks to its diverse resources, including flint-rich limestone massifs and caves that could be used as shelters.[4]

Located above the important Toulon spring, the Jambes site yielded evidence of the Upper Perigordian.[5]

Ancient times

In 700 B.C., the Isle valley was occupied by the Ligures, who were driven out around 500 B.C. by the Iberians.[6]

Around 200 BC, "the Petrocorii inhabited the region between the Dordogne and Vézère rivers", according to Venceslas Kruta.[7] During this period, they settled on the heights on the left bank of the Isle river, creating a fortified camp on the hills of Écornebœuf[8] and Boissière, in what is now Coulounieix-Chamiers, a fortified camp at La Boissière, also known as "Caesar's camp at Curade".[9][10] Between the two hills lies the sacred fountain of Les Jameaux,[11] probably dedicated to Ouesona, the mother-goddess who, according to Claude Chevillot, protected the beneficial waters. The Petrocorii were settled in Gallia, not Aquitaine, because before the Roman conquest, these two territories were separated by the Garumna river.[12]

In 52 BC, Vercingetorix asked the Petrocii to send 5,000 warriors to help him face Julius Caesar's Roman legions.[13]

In 27 BC, when Augustus reorganized the administration of Gallia, Périgueux became part of the province of Aquitaine.[14] The oppidum of La Boissière was abandoned and the Gallo-Roman city municipium Vesunna, future Périgueux, was created between 25 and 16 BC in a loop on the right bank of the Isle.[15] It benefited from Roman public power.[16] At that time, Vesunna was one of twenty-one cities in the province of Aquitaine.[17]

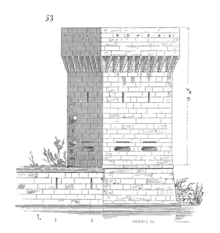

It was in the 1st century AD that the city, as a Roman town, underwent its greatest expansion, mainly in terms of urban planning, where the largest public monuments were built according to Roman plans, such as the forum, the amphitheatre and the thermae.[18] Throughout the 1st century, urban construction continued, not only enlarging existing buildings but also building more and more domus.[18] At the end of the 2nd century, following an invasion attributed to the Alemanni, the Roman city shrank to five and a half hectares,[19] retreating to a small plateau behind ramparts[20] built between 276 and 290.[6] Incorporating the north-western half of the Vesunna amphitheatre,[19] these walls were built using elements of the city's monuments (remnants of the ramparts remain), and this third city took the name Civitas Petrucoriorum ("city of the Petrocorii"),[15] the place that was to become "the Cité" (lit. french for "the town").[21] At the time, this enclosure comprised twenty-four towers, twenty-three curtain walls and four gates, of which only two remain today: the Porte Normande and the Porte de Mars.[19][22]

According to the geographer Strabo, the Petrocorii worked extensively with iron.[23]

At the beginning of the 5th century, the Visigoths ravaged Vesona, particularly its religious buildings, and settled on the site,[6] despite resistance organized in 407 by Pegasus, the occupant of the episcopal see.[24][25] Around 465, the king of the Visigoths, Euric, martyred the bishop and banned Catholic worship by closing down places of worship and suppressing the bishopric.[6] It was not until 506 that Bishop Chronope was able to restore worship and churches.[6]

Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

Frankish domination by the Salians

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Franks came to dominate the region in the late 5th century. As a result, the Cité became Christian in the 6th century, even though the spread of religion had already reached a large part of urban society.[26]

During the reign of the Merovingians, the territory passed from hand to hand, provoking numerous disputes over the division of inheritance between the descendants of Clovis after his death in 511. Childebert I inherited first, until his death in 558, after which the lands of Charibert I in 561, then those of Guntram in 567, became part of the Vesone territory. With the help of the Church and the people of Vesone, Gontran defended the city against the violent attacks of his brother Chilperic I and Chlothar I's bastard son Gundoald.[26]

In 766, as a result of the conflict with Waiofar, the Duke of Aquitaine, Pepin the Short exercised his terror in Périgord, razing the city walls, including that of the ancient city of Petrocores[27].

Norman attacks and the emergence of Puy-Saint-Front

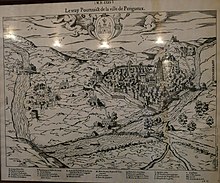

Between 840 and 865, the Normans made their way up the Isle, repeatedly pillaging and setting fire to the town.[28][29] Towards the end of the 10th century,[30] to the northeast and along the banks of the Isle, around a monastery that Bishop Frotaire (977-991) had built in honor of Saint Front, a new fortified center developed, known at the time as the "bourg du Puy-Saint-Front" (town of Puy-Saint-Front),[31] made up mainly of merchants, craftsmen and "laboureurs" (laborers).[32] To protect themselves from invaders, the two neighboring towns built walls.[19][30]

Central Middle Ages

The struggle between Church and nobility

Around 1040, Périgueux was troubled by unrest over the coinage minted by the Count of Périgord, Hélie II.[33] Shortly afterwards, the bishop Girard of Gourdon considered the coin to be defective and of poor quality, and banned it. Count Aldebert II, son of Hélie II, decided to prove, by force of arms, that it was suitable for him.[33][34] As a result, the town had to wage a long and bloody war against the Count.[34] The few dwellings under the protection of the new religious establishment of Puy-Saint-Front were burnt down around 1099; the convent and town were soon rebuilt.[31]

Pilgrims flocked to the site of Saint Front's relics.[35] In the 11th century, the number of houses increased and the settlement grew ever larger.[31] Over time, however, the town's inhabitants became increasingly divided. Around 1104, the burghers and citizens of the two neighboring communes came to blows; in the midst of this struggle, the burghers murdered Pierre de Périgueux, a descendant of a very old family of the Cité, and threw him into the Isle river.[36] Around 1130, in a quarrel with the convent, some of the burghers of Puy-Saint-Front allied themselves with Count Hélie-Rudel.[37] He was convinced that, having conquered Puy-Saint-Front, it would be easier for him to finally subdue the Cité, something none of his ancestors had managed to do.[37] At the same time, the counts dominated Puy-Saint-Front.[37]

Loyalty to the throne of England or the king of France?

Around 1150, Boson III, known as de Grignols, had a large, fortified tower built to command and watch over the Cité, which he had just seized.[38] But this attempt at oppression proved fatal for him and his descendants, as it aroused the anger of King Henry II of England, who had become Duke of Aquitaine by marriage.[38] The tower was destroyed in 1182, when, following a treaty with Count Helie V, Puy-Saint-Front fell into the hands of Henry II's son, Richard, who had all the fortifications built by him and his predecessor demolished.[38] At the same time, at the end of the 11th century, the "bourg du Puy-Saint-Front" (town of Puy-Saint-Front) was organized as a municipality.[39]

Having confiscated the Duchy of Aquitaine from John Lackland and reunited it with the crown of France, Philip Augustus demanded that the peoples and lords of this duchy pay him homage. In 1204, Hélie V and the inhabitants of the future city of Périgueux swore loyalty to the French monarch.[40]

Background to the treaty of alliance and the founding of Périgueux

For many years, Puy-Saint-Front and the counts lived in harmony.[41] The town's municipal organization had long been recognized and established by royal authority.[41] As for the Cité, it encountered no difficulties with the counts.[41] A first agreement between the two urban centers was established in 1217.[6] The state of peace lasted until 1239, and there was even a degree of trust between Count Archambaud II and the town. At that time, the latter paid him 50 pounds in exchange for relinquishing the annual rent of 20 pounds it owed him each Christmas.[41]

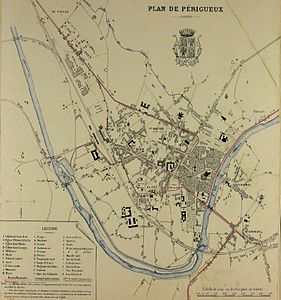

To ensure mutual protection and assistance, and to put an end to rivalries, Périgueux was founded in 1240 as a result of a treaty to unite[42] the two towns located just a few hundred meters apart:[43] the Cité - derived from the Gallo-Roman Vésone - the town of the bishop and the Count of Périgord,[21] and the middle-class town of Puy-Saint-Front.[30]

Renewed noble conflicts in Périgord

Hostilities between the Counts of Périgord and the new town lasted until 1250, when Bishop Pierre III de Saint-Astier[44] put an end to the discord. In the 13th century, new bourgeois settled in Périgueux to increase their land holdings by buying up vacant plots, while taking advantage of the privileged relationships they maintained with their parishes of origin, where they still kept properties.[45] Returning to the region of their ancestors, cloth merchants also settled in Périgueux, acquiring numerous rents and lands in a wide radius around the city.[45] Count Archambaud III had further disputes with Périgueux: in 1266, over the manufacture of coins, and in 1276 over their value.[44] This power struggle continued from generation to generation.[46] In principle, the counts claimed sovereign power, claiming to be the sole owners of the town of Puy-Saint-Front from the seventeenth century, then seeking royal favor in the fourteenth century.[46] These long conflicts came to an end in the 14th century, when the Count of Périgord, Roger-Bernard, son of Archambaud IV,[47] became the vassal of the English, who confirmed the possessions and jurisdiction[48] of the bourgeois of Périgueux (" Mayors, Consuls & Citizens of the City "), and Charles VI sent troops to their aid, after the bourgeois had been appealing to the royal justice system for more than eight years.[49]

Late Middle Ages

On April 16, 1321, a large number of lepers from the surrounding area were interned in Périgueux, then tortured before being either burned (the men) or walled up alive (the women).[50] In 1347, a flood on the Isle swept away part of the walls of Puy-Saint-Front.[51] From the middle of the 14th century, the countryside around Périgueux went through a period of serious crisis, marked in particular by a sharp fall in population due to the devastating effects of the Black Death and the Hundred Years' War.[52] During the Hundred Years' War, Périgueux remained loyal to the Kingdom of France, even when it was occupied by the English between 1360 and 1363.[53] In those years, the people of Périgueux submitted to the authority of Edward of Woodstock, nicknamed the Black Prince, who effectively levied the "fouage" (hearth tax) to feed the coffers of the principality of Aquitaine;[54] in 1367 alone, the town faced three tailles and five hearth taxes.[55] During this period, the counts and their descendants, most of whom lived in their castle at Montignac, pledged their allegiance to the kingdom of England. Charles VI confiscated their lands and titles in favour of his brother Louis d'Orléans. By transfer or marriage to the Orleans family, Périgord passed into the hands of the House of Châtillon in 1437, then into the House of Albret in 1481.

The shortage of manpower led to a contraction in cultivated land, with "deserts"[56] appearing at the very heart of the vineyards in the parish of Saint-Martin. In the 15th century, the town's activity picked up again and was dominated by merchants, as illustrated by the construction of Hôtels particuliers.[1]

Modern times

In May 1472, King Louis XI confirmed the town's privileges in his letters patent, following the death of his brother Charles, Duke of Guyenne.[57]

In 1524, the town suffered a terrible plague epidemic.[58] In 1530, the town's consuls decided to build a college. To this end, on 7 October 1531, the mayor and consuls bought the house of Pierre Dupuy. The college was mentioned in 1574 in François de Belleforest's Cosmographie universelle de tout le monde.[59] Jesuits expelled from Bordeaux arrived in Périgueux in July 1589. An agreement was signed on 23 December 1591 between the city authorities and Father Clément, provincial of the Jesuits. On 23 April 1592, Claudio Acquaviva, General of the Jesuits, approved an agreement concerning the new house of education entrusted to the Jesuits. The college was founded a second time on 9 October 1592.[60]

Taxes continued to rise, in particular the gabelle, which became unbearable for the inhabitants of Périgueux, so much so that they revolted in 1545.[61]

The Wars of Religion were more deadly for Périgueux than the Hundred Years' War. Périgueux was taken on 6 August 1575 by Calvinists[62][28] under the command of Favas and Guy of Montferrand, then pillaged and occupied.[63] Their strategy was to enter the town with soldiers disguised as peasants.[64] That same year, in Puy Saint-Front, the shrine and reliquary containing the remains of the holy bishop were stolen and taken to Château de Tiregand, where the saint's bones were thrown into the Dordogne.[63] Périgueux remained in Protestant hands for six years, until 1581,[6] when Captain Belsunce, governor of the town, allowed it to be taken by the Catholic Jean de Chilhaud. Périgord became part of the French crown in 1589, when its last Count, the son of Jeanne d'Albret, became King of France under the name of Henri IV.

In the seventeenth century, during the reign of Louis XIII, the town was on the border of a region that was subject to rebellion, extending as far south as the territory that is now the Dordogne department.[65] In 1636, during the Croquant rebellions, Périgueux was the scene of peasant revolts, but was not one of the towns or castles, such as Grignols, Excideuil and then Bergerac, that were taken by peasants during this period.[65] Their aim was to bring 6,000 men into Périgueux, steal the cannons and pursue the gabeleurs. On 1 May, the town was repatriated behind its ramparts and resisted the attackers. The large peasant army guarded the town day and night and stayed around the fortifications for three weeks, barricading the bridge to prevent the arrival of the troops of Jean Louis de Nogaret de La Valette, Duke of Épernon, commanded by his son Bernard de Nogaret de La Valette. La-Mothe-La-Forêt, the obscure gentleman who led this army of "communes", was finally victorious when the consensus declared a peasant payroll.[66]

In October 1651, during the Fronde, Périgueux welcomed the troops of the Prince of Condé.[67] In August 1653, during the Lorraine War, it was the only town in the south-west to remain hostile to the King, a situation that lasted until the following 16 September, when its inhabitants threw out the rebels.[67] In gratitude, the town's magistrates officially granted their wishes, leading to a pilgrimage to Notre-Dame-des-Vertus.[68] In 1669, the cathedral was moved from the ruined Saint-Étienne-de-la-Cité to Saint-Front cathedral, the former church of the abbey of the same name.[69] In autumn 1698, the misery of recent years had become unbearable, prompting the bishop of Périgueux to appeal to "the King's kindness".[70]

On 5 and 6 March 1783, the town experienced one of the highest floods of the Isle. The water rose to 5.21 metres, the highest level ever recorded for Périgueux,[71] drowning the causeway of the Pont Saint-Georges.[51] In 1789, the clergy, nobility and third estate came from all over the province to elect their deputies to the Estates-General. After the creation of the départements in 1790, the departmental assembly met alternately in Bergerac, Périgueux and Sarlat. Périgueux became the official capital of the Dordogne in September 1791.[72]

Contemporary times

19th century

From the First Empire to the July Monarchy

The Napoleonic Wars mobilised many young people in Périgueux. The wars also provided an opportunity for a number of prominent figures to shine, including General Pierre Daumesnil, Marquis Antoine Pierre Joseph Chapelle and Marshal Thomas-Robert Bugeaud. This mobilisation and requisitioning led to an increase in taxes. Most of the conscripts from Périgord died on the battlefield and the few men who returned were permanently wounded. As a result, numerous protests took place in front of the Dordogne prefecture.[73]

Under the First Empire, the town, seat of the prefecture,[74] was enlarged in 1813 by merging with the former commune of Saint-Martin.[75]

In 1815, the deputies from the Périgord were mostly in the ranks of the Ultras, facing the small number of liberal monarchists elected from 1824 onwards: the Dordogne was thus more in opposition to the ministry of Joseph de Villèle. At the end of the 1820s, they supported the Jean-Baptiste de Martignac ministry and then opposed that of Jules de Polignac.[76] In December 1836, a major flood of the river Isle swept away the dam at the Saint-Front mill by around twenty metres (70 to 80 feet), and on January 15 1843, the river reached a level comparable to the record flood of 1783.[51]

Second Republic

In the presidential election of 1848, the people of Périgueux voted overwhelmingly for Napoleon III (88.5% of the votes cast). [Note 1]After the coup d'état of 1851, the proclamation of the Second Empire on December 2 was widely approved in Périgueux; 78% of the population of the département said "yes" in 1851 and 78.3% in 1852. The people of Périgueux remained strongly attached to the Bonapartist regime, always electing the candidates officially declared by the Emperor.[Note 2] In the plebiscite of May 8 1870, 77.7% of registered voters in the Dordogne approved the liberalisation of the regime.[77]

Belle Époque

Following the merger of Saint-Martin and Périgueux in 1813,[78] the town's population doubled in around forty years (13,547 inhabitants were recorded in 1851).[79] The town was boosted by advances in river and road transport. The fact that Périgueux had been chosen as a prefecture led to an increase in the number of civil servants, professionals, trades and public services. In terms of economic growth, Périgueux overtook Bergerac, until then the leading town in Périgord.[80] However, its main economic activity remained agriculture until the 20th century.[81]

In 1857, Périgueux saw the arrival of the railway from Coutras[82] and, from 1862, the installation of repair workshops for the locomotives and carriages of the Compagnie du Paris-Orléans.[83] This activity still survives in the Toulon district at the beginning of the 21st century. The Périgueux-Coutras line was supplemented by links to Brive-la-Gaillarde in 1860, Limoges in 1862 and Agen in 1863, making it the town in the Dordogne with the most rail connections.[84] It was also in the 19th century that two architects worked in Périgueux. Louis Catoire built the Courthouse, the Coderc covered market and the Theatre - which has now disappeared - as well as various buildings on Place Bugeaud.[85] Paul Abadie restored Saint-Front cathedral.[86]

Périgueux became increasingly depopulated between 1866 and 1911, as the people of the region were drawn to metropolis such as Bordeaux and Paris. This led to a decline in the local population, taking into account the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 and the low birth rate, which was exceeded by the death rate. Nevertheless, the population grew, balanced by high emigration.[87]

From the 1880s onwards, Périgueux experienced a decline in the old iron and steel industry, supported by the wine crisis. Industrial productivity collapsed, but the modern systems of the second industrial revolution were unable to offset this deficit.[88]

World War I

From the summer of 1914, many farmers left their fields in the middle of harvest time. The people of Périgord helped to build shells in the workshops of the Compagnie du Paris-Orléans in particular, but did not take part in trench warfare. Strikes followed between 1917 and 1918. Although Périgueux was located in a rural area and its citizens were far from experiencing a period of famine, the first supply cards were issued at the town hall in 1918.[89]

Interwar period: "Périgueux La Rouge" (Red Périgueux)

Leninism affected only a minority of Périgueux's inhabitants. In the 1919 legislative elections, like most French citizens, the people of Périgueux voted for candidates opposed to Bolshevism. In the 1919 municipal elections, the Socialists won and Paul Bouthonnier became mayor of Périgueux. These political changes earned the town its nickname of "Périgueux La Rouge" during the interwar period.[90] In 1920, there was an upsurge in strikes, which ended in May of that year when 2,047 railway workers, 71% of the total workforce in the workshops, were suspended from their jobs. The Communist Party (PC) then took political power in Périgueux under Marcel Delagrange in 1921.[90] In those years, industry accounted for 13% of jobs in Périgueux.[91]

World War II

In 1939, following the advance of German forces into Alsace and Lorraine, the inhabitants of these two regions were evacuated and distributed throughout central and south-western France.[92] On 4 September 1939, Doctor Félix Gadaud, Senator and Mayor of Périgueux, announced the arrival of Alsatian refugees "at the rate of 3,000 a day".[93] From 5 September 1939, Périgueux welcomed thousands of Alsatians from Strasbourg and nineteen surrounding towns.[94][Note 3] Strasbourg town hall moved to 2 rue Voltaire, in the premises of the Chamber of Commerce.[95][96] The Strasbourg football club, Racing Club, was re-established as an amateur club in Périgueux for the 1939-1940 season, where it won the Dordogne championship.[97] The administrative services returned to Strasbourg in July 1940, but the mayor, Charles Frey, remained in Périgueux until 28 November 1944.[95]

Many Alsatians were evacuated by the French government in 1939 and those who remained were expelled by the Nazis from annexed Alsace in July 1940.[98] In December 1940, 12,000 Jews found refuge in the Dordogne. A rabbi, Elie Cyper - who died in deportation in 1944 - was appointed in Périgueux [99] as deputy to the rabbi of Périgueux, Victor Marx, who was overwhelmed by the influx of refugees. 1,200 Jews who had taken refuge in the Dordogne were either deported or shot, despite the help of the Périgourdine population.[100]

The regiments disbanded on French territory were authorised to organise the Armistice Army in the zone libre, to maintain order. In August 1940, the 26th infantry regiment became the new Dordogne regiment, based in Périgueux.[101] The Resistance gradually emerged in the town, with movements and networks being set up to produce and distribute forged papers and clandestine newspapers, for example. Resistance fighters joined the army and organised sabotage and attacks.[102] After serving as an ammunition depot for the Resistance, the Institution Saint-Joseph was used as a meeting place where, in June 1942, the Combat resistance movement was founded, which organised the local A.S. maquis and formed the 50th and 26th R.I..[103][104][105]

On 3 October 1942, the first bomb attack damaged the kiosk of the city's Légion française des combattants, located in Place Bugeaud, and caused a rift between the Gaullists and the Pétainists. The effects of Vichy's collaborationist policies eventually undermined Philippe Pétain's popularity, leading a number of poilus to join the Resistance.[106] On November 11 1942, German troops invaded the Zone Libre. German convoys entered the city and took up residence in the Daumesnil district, forcing the 26th infantry regiment to disband six days later. The Gestapo moved into what is now the Place du Général-de-Gaulle and became part of the local administration at the time, assisted by Paul Lapuyade, the departmental delegate for the Legion of French Volunteers who collected a great deal of information for the Nazis.[107]

In retaliation for the death of two German officers in Paris on the Pont des Arts, the French government, at the request of the German authorities, had 2,000 Jews arrested in France; 84 of them were arrested in the Dordogne between 23 and 28 February 1943, 69 of whom were interned in Périgueux at the Secrestat gymnasium, before being transferred to the Drancy, Gurs and Nexon internment camps.[108] The Resistance intensified during 1943, leading to a bomb attack on October 9, targeting the Gestapo headquarters for the first time. But reprisals were immediately launched, leading to the arrest of seventeen Resistance fighters and the deportation of most of them. On November 9, another attack on the Germans at the gendarmerie headquarters caused extensive material damage and injuries. A crackdown was immediately organised, targeting mainly Jews, of whom 1,672 were registered in the arrondissement and 700 in the town itself.[109] On December 13th 1943, a major sabotage operation instigated by the regional committee of the Francs-tireurs et partisans and carried out by men from Camp Wodli disabled one of the most powerful lifting cranes in France, which had been parked for repairs at the SNCF workshops in Périgueux.[Note 4][110]

On May 10 1944, the Vichy militia and police arrested 211 people and rounded them up in the Palace hall. They were then transferred to the Atlantic Wall construction sites for forced labour, interned in Haute-Vienne or deported to Germany.[111]

On D-Day, the Allies landed in Normandy. Resistance fighters from Périgord attacked military targets to paralyse the enemy. The Germans counter-attacked, killing more than 500 civilians. Faced with this situation, the newly-formed General Staff of the French Forces of the Interior set the Germans an ultimatum of August 17, but received no response. On August 18, a plan to surround Périgueux was under way. At the same time, the operation dragoon brought a sudden end to the city: Hitler decided to withdraw his troops based in the south of France. After initially having shot 35 Resistance fighters[112] who had been imprisoned in the Daumesnil district,[113] and then 14 others who had been interned, the Germans abandoned the town on 19 August 1944 without destroying it or putting up a fight.[114]

All that has been suffered here for the Motherland, all that has been hoped for the Motherland, all that has been offered to the Motherland, what a magnificent treasure! To say that we will not forget it is an understatement.

— Charles de Gaulle, Mur des Fusillés au quartier Saint-Georges (Wall of those shot in the Saint-Georges district), March 5, 1945[115]

After the war, the Fourth Republic

After heavy rainfall and an accelerated snowmelt, the Isle reached a hundred-year flood level, peaking at 4.50 metres on December 8 1944, causing 7,000 people to lose their homes and flooding a third of Périgueux.[71]

In 1945, Hans Kowar, a German prisoner of war, was working in the Bergerac region, at Nastringues, on a farm belonging to the family of the priest Henri Cellerier, who was teaching German in Périgueux.[116] The two men became friends and, on his return home, Kowar introduced Cellerier to his home town, Amberg. In 1961, a municipal delegation from Périgueux travelled to Amberg and the twinning was made official on 2 October 1965.[116] The Association des amis d'Amberg was set up in 1993, and to this day has given rise to numerous student exchanges,[117] such as the one that still takes place every year between the Clos-Chassaing college and the Erasmus Gymnasium.[118]

In 1946, a majority of Périgord residents voted "yes" to the draft Constitution of April 19. In the legislative elections in June, the Communists headed the list in the canton of Périgueux, as the French Communist Party (PCF) played an important role in the Périgord Resistance during the Second World War. On October 13 1946, Périgueux also adopted the Constitution of the Fourth Republic, but 36.2% of Périgourdins did not go to the polls that day.[119] Between 1946 and 1958, Périgueux was not impressed by Charles de Gaulle's early career.[120]

From the start of the Fifth Republic

From the referendum of September 28 1958 until the early 1970s, the Dordogne was influenced by the powerful left-wing majority in Périgueux.[120][121]

On March 1st 1960, the Advanced Section, Communications Zone (ETO) reorganised Europe and took command of all supply and ammunition depots in France, one of which was located in Périgueux.[122] In 1964, the 5e régiment de chasseurs à cheval moved to the Daumesnil district. Attached to the 15th infantry division in 1977, it took part in operations in Lebanon between 1986 and 1993 and in Yugoslavia from 1992 to 1994, when it was disbanded and left Périgueux.[123]

Between 1950 and 1970, the Barris faubourg developed on the left bank of the Isle.[62] In 1970, a protected area was created, encompassing a major part of Puy-Saint-Front.[124]

In 1971, the right-wing regained the majority in Périgueux under the Gaullist Yves Guéna.[125]

By 1987, the primary sector accounted for just 17% of the workforce in Périgueux, down from 49% in 1954, following the mechanization of productivity. Farms were becoming increasingly rare. While tenant farming was at its peak, metayage was disappearing. Traditional cash crops, meanwhile, remained dynamic on the local market. The "Trente Glorieuses" did not affect local industry, as the number of workers continued to rise.

Following the evacuation of 80,000 Alsatians to the Dordogne in 1939, mainly to Périgueux for those from Strasbourg, 20% remained in Périgord. As a result, relations were established, and Périgueux and Strasbourg signed a cooperation agreement in 2008, after deliberation by the Périgueux town council.[117][126] A stele in the park opposite the Lycée Bertran-de-Born commemorates Strasbourg's gratitude to Périgueux for welcoming refugees during World War II.[127]

Notes

- ^ At the time, the Dordogne was one of the most Bonapartist departments in France.

- ^ Among them were Thomas Dusolier, Timoléon Taillefer, Paul Dupont and Samuel Welles de Lavalette.

- ^ One in three residents is from StrasbourgLachaise 2000, p. 277.

- ^ A plaque in rue Pierre-Sémard at the Périgueux Technicentre commemorates this event.

References

- ^ a b Delattre, Daniel; et al. (May 2009). La Dordogne, les 557 communes (in French). Grandvilliers: Éditions Delattre. p. 140-142. ISBN 978-2-915907-50-6..

- ^ Cocula 2011, p. 20.

- ^ Penaud 2003, p. 416.

- ^ Cocula 2011, p. 19.

- ^ Célerier, G. (1967). "Le gisement périgordien supérieur des "Jambes", commune de Périgueux (Dordogne)" (in persee). Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française (in French). 64 (1): 53–68..

- ^ a b c d e f g Penaud 2003, pp. 113–117.

- ^ Les Celtes, histoire et dictionnaire (in French). Paris: Robert Laffont. 2000. p. 776..

- ^ Chevillot, Claude (February 10, 2016). "Coulounieix-Chamiers – Écorneboeuf". ADLFI. Archéologie de la France - Informations (in French)..

- ^ Penaud 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Colin, Anne (2007). "État des recherches récentes sur l'oppidum du camp de César (ou de La Curade), Coulounieix-Chamiers (Dordogne)". Aquitania (in French). 14. Bordeaux: 227–236. ISSN 2015-9749..

- ^ Wlgrin de Taillefer, Antiquités de Vésone, cité gauloise, remplacée par la ville actuelle de Périgueux (in French), tome 1, Périgueux, 1821, pp. 121-122 (read online)

- ^ Jules César, Commentaires sur la Guerre des Gaules (in French), livre I, 1.

- ^ Aubarbier, Jean-Luc; Binet, Michel; Mandon, Guy (1987). Nouveau guide du Périgord-Quercy (in French). Rennes: Ouest-France. p. 22-23. ISBN 2-85882-842-3..

- ^ "Noms antiques des villes & peuples de l'Aquitaine". Lexilogos (in French). Retrieved September 22, 2012..

- ^ a b Penaud 2003, pp. 573–574.

- ^ Moreau 1775, p. 20.

- ^ Cocula 2011, p. 29.

- ^ a b Lachaise 2000, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d Penaud 2003, p. 122-123.

- ^ "Petit tour d'horizon de la Ville". le site de la mairie de Périgueux. 28 January 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2012..

- ^ a b Penaud 2003, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 103.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 94.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 108.

- ^ Penaud, Guy (December 1999). Dictionnaire biographique du Périgord (in French). Périgueux: Fanlac editions. p. 732. ISBN 2-86577-214-4..

- ^ a b Lachaise 2000, p. 112.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 113.

- ^ a b Penaud 2003, pp. 369–370.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 119.

- ^ a b c Penaud 2003, pp. 424–426.

- ^ a b c Dessalles 1847, p. 8.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 143.

- ^ a b Dessalles 1847, p. 6.

- ^ a b Dessalles 1847, p. 7.

- ^ Aubarbier, Jean-Luc; Binet, Michel; Mandon, Guy (1987). Nouveau guide du Périgord-Quercy (in French). Rennes: Ouest-France. p. 39. ISBN 2-85882-842-3..

- ^ Penaud, Guy (December 1999). Dictionnaire biographique du Périgord (in French). Périgueux: Fanlac editions. p. 736. ISBN 2-86577-214-4..

- ^ a b c Dessalles 1847, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Dessalles 1847, p. 10.

- ^ Penaud 2003, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Dessalles 1847, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Dessalles 1847, p. 12.

- ^ « Traité de réunion de la Cité et de la ville de Périgueux (année 1240) », dans Le chroniqueur du Périgord et du Limousin (in French), 1854, pp. 45-47 (read online)

- ^ Dessalles 1847, p. 13.

- ^ a b Dessalles 1847, p. 15.

- ^ a b Marty 1993, p. 71.

- ^ a b Dessalles 1847, p. 55.

- ^ Dessalles 1847, p. 56.

- ^ Maur Dantine, Clément (1784). L'Art de vérifier les dates des faits historiques, des chartes, des chroniques et autres ancien monumens, depuis la naissance de Notre-Seigneur (in French). Paris: Alexandre Jombert. p. 384..

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 178.

- ^ Penaud 2003, pp. 291–292.

- ^ a b c Penaud 2003, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Dessalles 1847, p. 71.

- ^ Dessalles 1847, p. 75.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 169.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 170.

- ^ Marty 1993, p. 76.

- ^ Lettres patentes de Louis XI, Saintes, mai 1472 in Eusèbe de Laurière, Ordonnances des Rois de France de la troisièmme Race (in French), recueillies par ordre chronologique, imprimerie royale, 1820, p. 497 (read online).

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 200.

- ^ de Belleforest, François, Cosmographie universelle de tout le monde (in French), in Michel Sonnius, Paris, 1575, (lire en ligne)

- ^ Lambert, Ch., « Le Collège de Périgueux, des origines à 1792 » (in French), dans Bulletin de la Société historique et archéologique du Périgord, 1927, tome 54, pp. 72-85 (read online)

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 201.

- ^ a b "Archive Larousse : Grande Encyclopédie Larousse - Périgueux". le site des éditions Larousse (in French). Retrieved September 22, 2012..

- ^ a b Penaud 2003, pp. 223–226.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 210.

- ^ a b Marty 1993, p. 105.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, pp. 220–221.

- ^ a b Penaud 2003, p. 222.

- ^ "Pèlerinage de Notre-Dame de Sanilhac". PERIZOOM (in French) (96): 6. September 2013..

- ^ Penaud 2003, p. 465.

- ^ Marty 1993, p. 121.

- ^ a b Mankowski, Thomas, Le jour où l'Isle a noyé la ville (in French), Sud Ouest édition Périgueux of December 31, 2014, pp. 12-13.

- ^ Préfecture de la Dordogne. "Le cadre administratif : de la province à la région" (in French). Retrieved 18 September 2012..

- ^ Lachaise 2000, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Penaud 2003, pp. 412–414.

- ^ Penaud 2003, p. 491.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, pp. 257–259.

- ^ Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Saint-Martin, EHESS (in French).

- ^ Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Périgueux, EHESS (in French).

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 250.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 260.

- ^ "L'aventure du rail" (pdf). le site de la mairie de Périgueux. Périgueux le magazine des Périgourdins, No. 9 (in French). 2010. p. 34. Retrieved 18 September 2012..

- ^ Penaud 2003, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 259.

- ^ Penaud, Guy (December 1999). Dictionnaire biographique du Périgord (in French). Périgueux: éditions Fanlac. p. 204. ISBN 2-86577-214-4..

- ^ Laroche, Claude. Saint-Front de Périgueux: la restauration au 19th century (in French). p. 267-280., in the Congrès archéologique de France: 156e session - Monuments en Périgord - 1999. Paris: Société Française d'Archéologie. 1999..

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 261-262.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 263.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, pp. 269–271.

- ^ a b Lachaise 2000, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 276.

- ^ Nivet, Philippe. Les réfugiés de guerre dans la société française (1914-1946) (in French). p. 254..

- ^ Reumaux, Bernard; Wahl, Alfred (2009). Alsace, 1939-1945: la grande encyclopédie des années de guerre (in French). Strasbourg/Strasbourg/la Nuée bleue: Nuée bleue. p. 178. ISBN 978-2-7165-0647-2..

- ^ Chasain, Hervé, « Il y a 80 ans, l'arrivée des Alsaciens évacués » (in French), Sud Ouest édition Périgueux, June 6, 2019, p. 19.

- ^ a b Penaud 2003, pp. 537–538.

- ^ Service départemental de l'Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Descamps, Pierre-Marie; Ejnès, Gérard; Hennaux, Jacques (2007). Coupe de France: La folle épopée (in French). L'Équipe. p. 129. ISBN 978-2-915535-62-4. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- ^ Schwarzfuchs, Simon. "La dernière expulsion des Juifs d'Alsace" (in French). Site du judaïsme d'Alsace et de Lorraine. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- ^ Soïl, Henri (1946). "Elie Cyperucha dit Cyper". Site du Judaïsme d'Alsace et de Lorraine (in French).

- ^ "Etre juif en Dordogne entre 1939 et 1944". Site du Judaïsme d'Alsace et de Lorraine (in French). 2004.

- ^ Service départemental de l'Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre 2008, p. 3.

- ^ Service départemental de l'Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre 2008, p. 4.

- ^ Académie de Bordeaux. "Ces marques du souvenir : traces de qui ou de quoi ?". crdp.ac-bordeaux.fr (in French). Retrieved 22 July 2014..

- ^ "Historique de la construction de Saint-Joseph". stjo-stemarthe.com (in French). Retrieved 22 July 2014..

- ^ Ville de Périgueux (July 2013). "Périgueux dans la Seconde Guerre Mondiale - 1939-1945 Chemin de la Mémoire" (pdf) (in French). Retrieved 22 July 2014..

- ^ Service départemental de l'Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre 2008, p. 5.

- ^ Service départemental de l'Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre 2008, p. 6.

- ^ Hervé Chassain, « En mémoire des Juifs arrêtés et déportés en 1943 », Sud Ouest édition Dordogne, 22 février 2022, p. 13.

- ^ Service départemental de l'Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Service départemental de l'Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Siméon, Anne-Marie (May 11, 2012). "En souvenir de toutes les rafles". Sud Ouest (in French). Retrieved July 10, 2013..

- ^ Gillot; Maureau (2011). Résistants du Périgord (in French). Bordeaux: Sud Ouest..

- ^ Gillot; Maureau (2011). Sud Ouest (ed.). "Résistants du Périgord". Sud Ouest (in French). Bordeaux..

- ^ Service départemental de l'Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Audi, Antoine (2014). "Devoir de mémoire". À Périgueux (in French) (3): 2–3..

- ^ a b Penaud (2003), p. 279.

- ^ a b "Périgueux et l'extérieur". perigueux.fr (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2013..

- ^ "Discours de Michel Moyrand lors de la réception officielle de la délégation d'Amberg le 17 mai 2012" (pdf). perigueux.fr (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2013..

- ^ Lachaise 2000, pp. 282–283.

- ^ a b Lachaise 2000, p. 284.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, p. 285.

- ^ "US Army Communciations Zone, Europe". U.S. Army in Germany. Retrieved February 1, 2015..

- ^ Penaud 2003, p. 119.

- ^ Penaud 2003, p. 525.

- ^ Lachaise 2000, pp. 286–287.

- ^ "Périgueux et Strasbourg, villes sœurs". perigueux.fr (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2013..

- ^ Service départemental de l'Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre 2008, p. 2.