Adélaïde Labille-Guiard

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard | |

|---|---|

Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, 1785, the two pupils are Marie Capet and Marie-Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond | |

| Born | Adélaïde Labille 11 April 1749 Paris, France |

| Died | 24 April 1803 (aged 54) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Miniatures, painting, pastels |

| Movement | Rococo to Neoclassicism |

| Spouses | |

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (née Labille; 11 April 1749 – 24 April 1803), also known as Adélaïde Labille-Guiard des Vertus, was a French miniaturist and portrait painter. She was an advocate for women to receive the same opportunities as men to become great painters. Labille-Guiard was one of the first women to become a member of the Royal Academy, and was the first female artist to receive permission to set up a studio for her students at the Louvre.[1]

Early life and studies

Adélaïde Labille was born on April 11, 1749 in Paris. Her father, Claude Labille was a haberdasher.[2][3]

Labille-Guiard became a master at miniatures, pastels, and oil paintings. Little is known about her training due to the practices of the 18th century which dictated masters (who were predominately male) should not take on female pupils. During this time, women were perceived as incapable to follow instruction alongside men. During her adolescence, Labille-Guiard studied miniature painting with oil painter François-Élie Vincent and her early work was exhibited at the Académie de Saint-Luc.

Labille-Guillard married Louis-Nicolas Guiard in 1769, but separated from him eight years later, already able to support herself through her artwork.[4] She apprenticed with the pastel master Quentin de la Tour until 1774. From 1776 to 1780, she began to study oil painting with her childhood friend François-André Vincent (the eldest son of François-Élie Vincent), who would become her husband.[5][3]

Accomplishments

Exhibitions at the Académie de Saint-Luc

Labille-Guiard was admitted to the Académie de Saint-Luc in 1767 when she was twenty years old. Her admission piece has since disappeared and sadly no records of its existence survive today. The Académie de Saint-Luc provided Labille-Guiard with a space to practice art professionally. In 1774, she exhibited her work at its Salon. This show was so successful that the Royal Academy took offence, and with the backing of the monarchy, issued an edict in March 1776 abolishing “guilds, brotherhoods, and communities of arts and crafts”, forcing the Académie de Saint-Luc to close its doors in 1777. However, this did not stop Labille-Guiard's ambitions as an artist.

Becoming a member of the Royal Academy

Once the Académie de Saint-Luc closed its doors, Labille-Guiard began to learn oil painting, so she could apply to the Royal Academy which required her to present at least one oil painting for admission. During the late 1770s, she painted several portraits of leading academicians, creating contacts with the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture.[5]

Labille-Guiard chose to display some of her work at the Salon de la Correspondance in 1779 and 1783. This included her self-portrait in pastel and oil portraits, which were well received by critics. Labille-Guiard's talent as an oil painter and pastellist was quickly noticed, and she received national recognition, ultimately leading to her acceptance into the Royal Academy. On May 31, 1783, Labille-Guiard was accepted as a member of the French Academie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. Her rival, Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, was also elected on that day; the two of them were the first women to be inducted.[4] Both Labille-Guiard and Vigée Le Brun were immediately criticized following their admission by those who were furious at women's entry; Labille-Guiard suffered attacks against both her art and character.[7] One anonymous pamphlet Suite de Malborough au Salon 1783, accused Labille-Guiard of exchanging sexual favors for help with painting. The pamphlet punned on François-André Vincent's name (though still unmarried, he was her rumored paramour), saying that Labille Guiard had "vignt cents" (twenty-hundreds, or two thousand) lovers.[8] Still, becoming accepted into the Royal Academy opened doors for Labille-Guiard as she gained patronage from the royal family.

Painter for the Royal Family

Through pure artistic ability and talent, Labille-Guiard became a painter for the Royal family. Her royal patrons included the aunt of Louis XVI of France, Princess Marie Adélaïde and her sister Victoria Louise, and the King's sister Elizabeth and earned her a government pension of 1,000 livres. In 1787, she became peintre des mesdames, a position that led her to painting Madame Adélaïde and Madame Victoire.[5] The portrait of Adélaïde completed in 1787 was one of Labille-Guiard's largest and most ambitious work to that date. She was later commissioned in 1788 by the King's brother, the Count of Provence (later Louis XVIII of France). She was instructed to paint him at the centre of a large historical work, Réception d'un chevalier de Saint-Lazare par Monsieur, Grand maître de l'ordre. In 1795 she obtained artist's lodging at the Louvre (following a decade-long campaign)[3] and a new pension of 2,000 livres. She was the first woman artist to be permitted to set up a studio for herself and her students at the Louvre.[9]

- Paris society portraits by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard

-

Madame Alexis (Adélaïde Prévost)

Style and context

Labille-Guiard often did not fit comfortably within the boundaries of feminine virtue in the 18th century.[1] In order to appeal to a wide variety of viewers including upper-class men and women, she often incorporated recent fashions into her paintings, which allowed her to showcase her artistic ability. She was good at rendering details, such as showing luxurious folds and layers of complex skirts that were in fashion at the time. However, often she painted with a twist such as having women face directly at the viewer or with a low neckline, which was an uncommon practice in the 18th century when portraying women.

Further evidence of Labille-Guiard's boldness can be seen in her self-portraits, which leave her exposed slightly more than usual, but not enough to evoke allegations of promiscuous behaviour. This is seen in her painting Self-Portrait with Two Pupils. Unlike some other paintings of female artists in the 18th century, Labille-Guiard chose to depict herself actively working rather than passive and at rest. Labille-Guiard also pushed against other restrictions, such as those that limited the number of females that could attend the Royal Academy. By depicting two female students in Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Labille-Guiard suggests more women should be allowed in to the Royal Academy. In this sense, Labille-Guiard was daring, but not too daring as to sabotage her reputation and lose the respect she worked hard to gain within the art world.

At the time, female artists were frequently related to the goddess Minerva. Therefore, Labille-Guiard and her rival Vigée Le Brun were both referred to as "modern Minervas."[10] Their rivalry was encouraged by both academicians and patrons at court.[5]

Advocate for young female artists

Labille-Guiard had an impact on her young female artists. In a letter written by a mother whose daughter studied painting with a female academic, (who, based on the description, seems to be Labille-Guiard) she explained that the teacher insisted on maintaining the highest standards of modesty in her studio.[1] Her commitment for female students was evident throughout her membership at the Royal Academy. At a meeting held on September 23, 1790, Labille-Guiard proposed that women be admitted in unlimited numbers and be permitted to serve on the institution's governing board. Both motions were approved.[1] However, conservatives of the Academy turned it down and criticized Labille Guiard as a "Jeanne d'Arc", and "a hen amongst roosters," and she was similarly condemned by the radicals.[2]

Labille-Guillard continued to advocate for women, presenting the National Assembly with a memoir about the education of young women deprived of fortune, which was referenced by Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord in his work.[2]

In the face of revolution

Instead of fleeing during the French Revolution of 1789, Labille-Guiard stayed in France. However, the royal connections she made throughout her career made her a political suspect. She attempted to position herself as an artist for the Republic. She donated funds to the nation's treasury and painted thirteen members of the National Assembly (French Revolution), including Maximilien Robespierre and Alexandre de Beauharnais.[3][8] In 1791, she and Jacques-Louis David were commissioned by the legislature to paint Louis XVI handing the constitution to his son, which was never completed.[8][2] From 1792, she split her time between Paris and the village Pontault-en-Brie, where she fled with Vincent, two students, and others.[8][3] In 1793 she was ordered to destroy some of her royalist works, including the unfinished commission for the Count of Provence. The exile of the Comte of Provence meant Labille-Guiard had not only lost her last royal patron, but she also did not receive a cent of the agreed-upon 30,000 livres.[11] The Revolution further hurt her career when the royal sisters emigrated in February 1791 without paying for several portraits they had commissioned Labille-Guiard to paint. Labille-Guillard briefly left Paris for several years at this time, but returned. In 1795, she obtained lodging at Louvre, and continued to paint and exhibit portraits at the Salons until 1800, the year she married her former teacher, François-André Vincent in 1800.[4][2] The pastel portraits of Marie Adélaïde, Victoire-Louise, and Élisabeth stayed in Labille-Guiard's possession until she died from an illness on April 24, 1803.[11]

Legacy

Among the public collections holding works by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard are the Getty Museum, the Phoenix Art Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, the Honolulu Museum of Art, Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth, Texas), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.), the National Museum in Warsaw, the National Museum of Women in the Arts (Washington, D.C.), the Speed Art Museum (Kentucky) and Versailles.

Recently a large pastel by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard was unearthed. It is assumed that it is an earlier version of the Porträt der Mme. Clodion. The photograph is attached[12]

Labille-Guiard is a featured figure on Judy Chicago's installation piece The Dinner Party, being represented in one of the 999 tiles of the Heritage Floor. She is listed under the place setting of Artemisia Gentileschi[13][14]

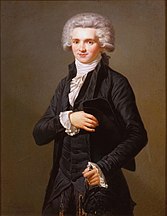

Gallery

-

The comedian Tournelle

-

Marie-Gabrielle Capet, study

-

Madame de Genlis, 1780

-

Marie-Gabrielle Capet, 1785

-

Joachim Lebreton, 1795

-

François-André Vincent, 1795

-

Mme Dugazon in the Role of Babet, 1775 or 1790

-

Portrait of a Man

-

Madame Charles Mitoire with her children, 1783

-

Portrait of Duchesse d'Aiguillon, 1790

Notes

- ^ a b c d Auricchio.

- ^ a b c d e Concise Dictionary of Women Artists, edited by Delia Gaze, Taylor & Francis Group, 2001.

- ^ a b c d e Nicholson, Kathleen (2003). "Labille-Guiard [née Labille], Adélaïde". Grove Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T048514. ISBN 9781884446054.

- ^ a b c Palmer, Allison Lee. Historical Dictionary of Neoclassical Art and Architecture, Rowman & Littlefield Unlimited Model, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- ^ a b c d Milam, Jennifer D.. Historical Dictionary of Rococo Art, Scarecrow Press, Incorporated, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- ^ Pajou sculpted the father of Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Claude Edme Labille, described as a fashion merchant, in 1784; the marble bust was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1785, and is now in the Louvre (N 15487).

- ^ Helm, W. H.. Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun, Parkstone International, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- ^ a b c d Auricchio, Laura (1 January 2008), "Labille-Guiard, Adélaïde", The Oxford Encyclopedia Women in World History, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195148909.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9, retrieved 21 May 2023

- ^ Christiane, Weidemann (2008). 50 women artists you should know. Larass, Petra., Klier, Melanie, 1970-. Munich: Prestel. ISBN 9783791339566. OCLC 195744889.

- ^ Women, Art and the Politics of Identity in Eighteenth-Century Europe, edited by Melissa Hyde, and Jennifer Milam, Taylor & Francis Group, 2003. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- ^ a b De Jesús, Mary Sprinson (2008). "Adélaïde Labille-Guiard's Pastel Studies of the Mesdames de France". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 43: 157–172. doi:10.1086/met.43.25699092. JSTOR 25699092. S2CID 191391110.

- ^ "Adélaïde Labille-Guiard".

- ^ "Adelaide Labille-Guiard". Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: The Dinner Party: Heritage Floor: Adélaïde Labille-Guiard. Brooklyn Museum. 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ Chicago, 157–158.

Bibliography

- Auricchio, Laura. Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist in the Age of Revolution, Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009.

- Baetjer, Katharine. "Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803)" at Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, www.metmuseum.org, posted June 2016.

- Chicago, Judy. The Dinner Party: From Creation to Preservation, London: Merrell, 2007. ISBN 1-85894-370-1

- Passez, Anne-Marie. Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, Paris: 1973.

- Portalis, Roger (1901). "Adélaïde Labille-Guiard" in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne: 1901, p. 352–367.

- Portalis, Roger (1902). Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Paris: Imprimerie Georges Petit, 1902.

- Cailleux, Jean. "Portrait of Madame Adélaïde of France, Daughter of Louis XV," Burlington Magazine (vol.3, March 1969), supp.i-vi.

External links

- Labille-Guiard, Adélaïde at Benezit Dictionary of Artists

- Labille-Guiard (née Labille), Adélaïde by Kathleen Nicholson at Grove Art Online

- Royalists to Romantics: Spotlight on Adélaïde Labille-Guiard at National Museum of Women in the Arts

- Biography of Adélaïde Labille-Guiard from the Société Internationale pour l'Étude des Femmes de l'Ancien Régime

- Labille-Guiard, Adélaïde at Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800, online edition